Mosasaurinae

The Mosasaurinae are a subfamily of mosasaurs, a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine squamates. Members of the subfamily are informally and collectively known as "mosasaurines" and have been recovered from every continent except for South America.[1]

| Mosasaurines | |

|---|---|

| |

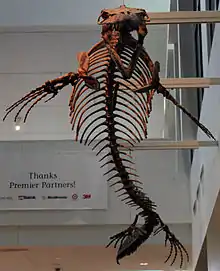

| Mounted skeleton of Mosasaurus conodon, Minnesota Science Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | †Mosasauroidea |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Mosasaurinae Gervais, 1853 |

| Type species | |

| †Mosasaurus hoffmannii Mantell, 1829 | |

| Genera | |

| |

The lineage first appears in the Turonian and thrived until the mass extinction event at the end of the Maastrichtian. They ranged in size from some of the smallest known mosasaurs (Carinodens, 3–3.5 meters), to medium-sized taxa (Clidastes, 6+ meters), to the largest of the mosasaurs (Mosasaurus hoffmannii) potentially reaching about 15 m in length. Many genera of mosasaurines were either piscivorous or generalists, preying on fish and other marine reptiles, but one lineage, the Globidensini, evolved specialized crushing teeth, adapting to a diet of ammonites and/or marine turtles.

Though represented by relatively small forms throughout the Turonian and Santonian, such as Clidastes, the lineage diversified during the Campanian and had by the Maastrichtian grown into the most diverse and species-rich mosasaur subfamily.[2]

The etymology of the group derives from the genus Mosasaurus (Latin Mosa = "Meuse river" + Greek sauros = "lizard").

Description

Russell (1967, pp. 123–124)[3] defined the Mosasurinae as differing from all other mosasaurs as follows: "Small rostrum present or absent anterior to premaxillary teeth. Fourteen or more teeth present in dentary and maxilla. Cranial nerves X, XI, and XII leave lateral wall of opisthotic through two foramina. No canal or groove in floor of basioccipital or basisphenoid for basilar artery. Suprastapedial process of quadrate distally expanded. Dorsal edge of surangular thin lamina of bone rising anteriorly to posterior surface of coronoid...At least 31, usually 42–45 presacral vertebrae present. Length of presacral series exceeds that of postsacral, neural spines of posterior caudal vertebrae elongated to form distinct fin. Appendicular elements with smoothly finished articular surfaces, tarsus and carpus well ossified." In his 1997 revision of the phylogeny of the Mosasauroidea, Bell (pp. 293–332) retained the Mosasaurinae as a clade, though he reassigned Russell's tribe Prognathodontini to the Mosasaurinae and recognized a new tribe of mosasaurines, the Globidensini.[4][5]

The subfamily is generally recognised as containing two subdivisions, the tribes Globidensini (Globidens and its closest relatives) and Mosasaurini (Mosasaurus and its closest relatives). A third tribe, the Prognathodontini (Prognathodon and its closest relatives, such as Plesiotylosaurus), is also used on occasion.[3] "Clidastini" or the adjective "clidastine" is also used sometimes, but generally refers to an adaptive grade close to and containing the genus Clidastes, rather than an actual clade.[6]

Relationships

Cladogram of the Mosasaurinae modified from Simões et al. (2017):[7]

| Mosasaurinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- "Fossilworks: Mosasaurinae". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Polcyn, Michael J.; Jacobs, Louis L.; Araújo, Ricardo; Schulp, Anne S.; Mateus, Octávio (2014-04-15). "Physical drivers of mosasaur evolution". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Physical drivers in the evolution of marine tetrapods. 400: 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.05.018.

- Russell, Dale. A. (6 November 1967). "Systematics and Morphology of American Mosasaurs" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History (Yale University).

- Bell, G. L. Jr., 1997. A phylogenetic revision of North American and Adriatic Mosasauroidea. pp. 293–332 In Callaway J. M. and E. L Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pp.

- Gervais, P. 1853. Observations relatives aux reptiles fossiles de France. Acad. Sci. Paris Compt. Rendus 36:374–377, 470–474.

- Caldwell, Michael; Konishi, Takuya (2007). "Taxonomic re-assignment of the first-known mosasaur specimen from Japan, and a discussion of circum-pacific mosasaur paleobiogeography". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (2): 517–520. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[517:trotfm]2.0.co;2.

- Simões, Tiago R.; Vernygora, Oksana; Paparella, Ilaria; Jimenez-Huidobro, Paulina; Caldwell, Michael W. (2017-05-03). "Mosasauroid phylogeny under multiple phylogenetic methods provides new insights on the evolution of aquatic adaptations in the group". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0176773. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0176773. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5415187. PMID 28467456.

Further reading

- Kiernan, C. R. (2002). "Stratigraphic distribution and habitat segregation of mosasaurs in the Upper Cretaceous of western and central Alabama, with an historical review of Alabama mosasaur discoveries". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (1): 91–103. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0091:sdahso]2.0.co;2.

- Williston, S. W. (1897). "Range and distribution of the mosasaurs with remarks on synonymy". Kansas University Quarterly. 4 (4): 177–185.