Moulin Rouge (1952 film)

Moulin Rouge is a 1952 British drama film directed by John Huston, produced by John and James Woolf for their Romulus Films company and released by United Artists. The film is set in Paris in the late 19th century, following artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in the city's bohemian subculture in and around the burlesque palace the Moulin Rouge. The screenplay is by Huston, based on the 1950 novel by Pierre La Mure. The cinematography was by Oswald Morris. This film was screened at the 14th Venice International Film Festival where it won the Silver Lion.

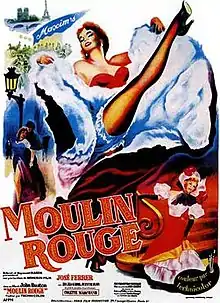

| Moulin Rouge | |

|---|---|

French theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | John Huston |

| Produced by | John and James Woolf |

| Written by | John Huston Anthony Veiller Pierre La Mure (Novel) |

| Starring | José Ferrer Zsa Zsa Gabor Suzanne Flon |

| Music by | Georges Auric William Engvick |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Ralph Kemplen |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists (US) British Lion Films (UK) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | USD$1.5 million (approx. £967,785) |

| Box office | $9 million[1] |

The film stars José Ferrer as Toulouse-Lautrec, with Zsa Zsa Gabor as Jane Avril, Suzanne Flon, Eric Pohlmann, Colette Marchand, Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, Katherine Kath, Theodore Bikel, and Muriel Smith.

Plot

In 1890 Paris crowds pour into the Moulin Rouge nightclub as artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec finishes a bottle of cognac while sketching the club's dancers. The club's regulars arrive: singer Jane Avril teases Henri charmingly, dancers La Goulue and Aicha fight, and owner Maurice Joyant offers Henri free drinks for a month in exchange for painting a promotional poster. At closing time, Henri waits for the crowds to disperse before standing to reveal his four-foot six-inch stature. As he walks to his Montmartre apartment, he recalls the events that led to his disfigurement.

In flashbacks it is revealed that Henri was a bright, happy child, cherished by his parents, the fabulously wealthy Count and Countess de Toulouse-Lautrec. But as a boy Lautrec fell down a flight of stairs and his legs failed to heal because of a genetic weakness, likely resulting from his parents being first cousins. His legs stunted and pained, Henri loses himself in his art, while his father leaves his mother to ensure that they have no more children. As a young adult, Henri proposes to the woman he loves but, when she tells him that no woman will ever love him, he leaves his childhood home in despair to begin a new life as a painter in Paris.

Back in the present, street walker Marie Charlet begs Henri to rescue her from police sergeant Patou. Henri wards off the policeman by pretending to be her escort, after which she insists on following him home. There, she acknowledges his disability with complete dispassion and although he is at first angry, Lautrec is impressed by her lack of judgement of his condition. He allows her to stay and comes to realize that the poverty and brutality of her childhood have made her cruel, ignorant and sly but also free of society's hypocrisy. Within days, he is buying her gifts and singing as he paints, until Marie takes his money and stays out all night.

Henri waits in agony for her return, but when she finally does he tells her to leave at once. Realizing he loves her, Marie vows to stay and love him back. Although they fight constantly and he knows he can't trust her, Henri is unable to break with her. A final battle breaks out when Marie demands to be paid for posing for a portrait and flies into a rage when she thinks the portrait is unflattering. By morning, she begs him to take her back, but he refuses. He begins drinking himself to death until his landlady calls his mother, who urges him to save his health by finding Marie.

Henri searches Marie's working-class neighborhood, finally discovering her at a café, blind drunk and sobbing. Marie reveals that she stayed with him only to procure money for her boyfriend, who has dumped her. When she adds that his touch made her sick, Henri returns to his apartment, and turns on the gas vents. As he sits waiting to die, he is suddenly inspired to finish his Moulin Rouge poster and, brush in hand, turns the gas vents off and opens the windows. Having passed through the crisis, he asks Sergeant Patou to secretly give Marie enough money to lift her out of her abject misery.

The next day, Henri brings the poster to the dance hall and, though the style is unusual, Maurice accepts it. Henri works for days at the lithographers, blending his own inks to perfect the vivid colors. When he finishes the poster, which shows a woman dancing with her frilly panties exposed, it becomes an instant sensation and the Moulin Rouge opens to high society. His father denounces Henri for the "pornographic" work. Over the next ten years, Henri records the Parisian demimonde in brilliant paintings. His irascibility causes him to fight constantly with other painters but his broker loyally fights for his art to be accepted. By 1900 he is famous, but still terribly lonely.

One morning he sees an elegant young woman standing at the edge of Pont Alexandre III over the Seine River. Thinking she might be suicidal, he stops to talk to her. She tells him she isn't going to jump and throws a key into the water. Days later, Jane Avril goes shopping with Henri, where the young woman is modeling gowns at a dress shop. She is Myriamme, Jane's friend who, unlike Jane, lives on her own earnings and not the patronage of rich lovers. Myriamme is a great admirer of Henri's paintings, and Henri is shocked to discover that she bought the portrait of Marie Charlet years before in a flea market.

Myriamme is Marie's opposite: principled, kind and cultured. She reveals to Henri that the key she threw into the water belonged to a wealthy and dashing man, Marcel de la Voisier, who asked her to be his mistress, but not his wife. While Henri continues to bitterly decry the possibility of true love, he falls in love with Myriamme. One night the two see dancer La Goulue on the street drunkenly insisting that she was once a star. Henri realizes that the Moulin Rouge has become a respectable establishment and is no longer the home for misfits.

Myriamme informs Henri that Marcel has finally asked her to marry him. Certain she loves the more handsome man, he bitingly congratulates her for trapping Marcel. Myriamme asks Henri if he loves her, but, believing that she is only trying to spare his feelings, he lies and tells her he does not. The next day Henri receives a letter from Myriamme telling him that she loves him, not Marcel, but she believes Henri's bitterness over Marie has poisoned any chance for them to be happy together. Rushing to Myriamme's apartment, Henri finds she has left to marry Marcel. Weeks later, while sitting in a sleazy dive drinking relentlessly, Henri obsessively reads Myriamme's note. Patou, now an inspector, is called to help him. Once home, in a state of delirium tremens, Henri hallucinates that he sees cockroaches, and in trying to drive them away, accidentally falls down a flight of stairs.

Near death, Henri is brought to his family's chateau. After a priest reads the last rites, his father tearfully informs Henri that he is to be the first living artist to be shown in the Louvre, and begs for forgiveness. Dying, Henri turns his head and smiles as phantasmal characters from his Moulin Rouge paintings, including Jane Avril, dance into the room to bid him goodbye.

Cast

- José Ferrer as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec / Comte Alphonse de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Zsa Zsa Gabor as Jane Avril

- Colette Marchand as Marie Charlet

- Suzanne Flon as Myriamme Hyam

- Claude Nollier as Countess Adele de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Katherine Kath as La Goulue

- Muriel Smith as Aicha

- Mary Clare as Madame Louet

- Lee Montague as Maurice Joyant

- Walter Crisham as Valentin le Cesosse

- Theodore Bikel as King Milan IV of Serbia

- Peter Cushing as Marcel de la Voisier

- Christopher Lee as Georges Seurat

- Michael Balfour as Dodo

- Eric Pohlmann as Picard

Production

In the film, Ferrer plays both Henri and his father, the Comte Alphonse de Toulouse-Lautrec. To transform Ferrer into Henri required the use of platforms and concealed pits as well as special camera angles, makeup and costumes. Short body doubles were also used. In addition, Ferrer used a set of knee-pads of his own design allowing him to walk on his knees . He received high praise not only for his performance, but for his willingness to have his legs strapped in such a manner simply to play a role.

It was reported that John Huston asked cinematographer Oswald Morris to render the color scheme of the film to look "as if Toulouse-Lautrec had directed it".[2] Moulin Rouge was shot in three-strip Technicolor. The Technicolor projection print is created by dye transfer from three primary-color gelatin matrices. This permits great flexibility in controlling the density, contrast, and saturation of the print. Huston asked Technicolor for a subdued palette, rather than the sometimes-gaudy colors "glorious Technicolor" was famous for. Technicolor was reportedly reluctant to do this.

The film was shot at Shepperton Studios, Shepperton, Surrey, England, and on location in London and Paris.

Reception

During its first year of release it earned £205,453 in UK cinemas[3] and grossed $9 million at the North American box office.[1]

According to the National Film Finance Corporation, the film made a comfortable profit.[4]

Ferrer received 40 percent of the proceeds from the film as well as other rights. This remuneration gave rise to a prominent U.S. Second Circuit tax case, Commissioner v. Ferrer (1962), in which Ferrer argued that he was taxed too much.[5]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[6] | Best Motion Picture | John Huston | Nominated |

| Best Director | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor | José Ferrer | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Colette Marchand | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction – Color | Paul Sheriff and Marcel Vertès | Won | |

| Best Costume Design – Color | Marcel Vertès | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | Ralph Kemplen | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Film from any Source | Moulin Rouge | Nominated |

| Best British Film | Nominated | ||

| Most Promising Newcomer to Film | Colette Marchand | Nominated | |

| British Society of Cinematographers | Best Cinematography | Oswald Morris | Won |

| Golden Globe Awards | Most Promising Newcomer – Female | Colette Marchand | Won |

| National Board of Review Awards | Top Foreign Films | Moulin Rouge | Won |

| Venice Film Festival | Golden Lion | John Huston | Nominated |

| Silver Lion | Won | ||

| Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Written American Drama | Anthony Veiller and John Huston | Nominated |

The film was not nominated for its color cinematography, which many critics found remarkable. Leonard Maltin, in his annual Movie and Video Guide declared: "If you can't catch this in color, skip it."

In an interview shortly after his successful film version of Cabaret opened, Bob Fosse acknowledged John Huston's filming of the can-can in Moulin Rouge as being very influential on his own film style.

The Moulin Rouge theme song became well known and made it onto the record industry charts.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[7]

Digital restoration

The film was digitally restored by FotoKem for Blu-ray debut. Frame-by-frame digital restoration was done by Prasad Corporation removing dirt, tears, scratches and other defects.[8][9] In April 2019, a restored version of the film from The Film Foundation, Park Circus, Romulus Films, and MGM was selected to be shown in the Cannes Classics section at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival.[10]

See also

- Moulin Rouge, 1928 film

- Moulin Rouge, 1934 film

- Moulin Rouge!, 2001 film

References

- "Some of the Top UA Grossers". Variety. 24 June 1959. p. 12. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Tom Vallance, "Obituary: Sir John Woolf", The Independent, 1 July 1999

- Vincent Porter, 'The Robert Clark Account', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol 20 No 4, 2000 p.499

- U.S. MONEY BEHIND 30% OF BRITISH FILMS: Problems for the Board of Trade The Manchester Guardian (1901-1959) [Manchester (UK)] 4 May 1956: 7

- See 304 F. 2d 125 - Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Ferrer , OpenJurist

- "NY Times: Moulin Rouge". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- Prasad Corporation, Digital Film Restoration Archived 13 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "FotoKem - Home". fotokem.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "Cannes Classics 2019". Festival de Cannes. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2019.