Mufti

A mufti (/ˈmʌfti/; Arabic: مفتي) is an Islamic jurist qualified to issue a nonbinding opinion (fatwa) on a point of Islamic law (sharia).[1][2] The act of issuing fatwas is called iftāʾ.[3] Muftis and their fatwas played an important role throughout Islamic history, taking on new roles in the modern era.[4][5]

Tracing its origins to the Quran and early Islamic communities, the practice of ifta crystallized with the emergence of the traditional legal theory and schools of Islamic jurisprudence (madhhabs).[1][2] In the classical legal system, fatwas issued by muftis in response to private queries served to inform Muslim populations about Islam, advise courts on difficult points of Islamic law, and elaborate substantive law.[4] In later times, muftis also issued public and political fatwas that took a stand on doctrinal controversies, legitimized government policies or articulated grievances of the population.[6][5]

Traditionally, a mufti was seen as a scholar of upright character who possessed a thorough knowledge of the Quran, hadith and legal literature.[1] Muftis acted as independent scholars in the classical legal system.[4] Over the centuries, Sunni muftis were gradually incorporated into state bureaucracies, while Shia jurists in Iran progressively asserted an autonomous authority starting from the early modern era.[5]

With the spread of codified state laws and Western-style legal education in the modern Muslim world, muftis generally no longer play their traditional role of clarifying and elaborating the laws applied in courts.[3][4] However, muftis have continued to advise the general public on other aspects of sharia, particularly questions regarding religious rituals and everyday life.[3][7] Some modern muftis are appointed by the state to issue fatwas, while others serve on advisory religious councils.[1] Still others issue fatwas in response to private queries on television or over the internet.[5] Modern public fatwas have addressed and sometimes sparked controversies in the Muslim world and beyond.[5]

The legal methodology of modern ifta often diverges from pre-modern practice.[8] While the proliferation of contemporary fatwas attests to the importance of Islamic authenticity to many Muslims, little research has been done to determine to what extent the Muslim public continues to acknowledge the religious authority of muftis or heeds their advice.[8]

Terminology

The word mufti comes from the Arabic root f-t-y, whose meanings include "youth, newness, clarification, explanation."[4] A number of related terms derive from the same root. A mufti's response is called a fatwa. The person who asks a mufti for a fatwa is known as mustafti. The act of issuing fatwas is called iftāʾ.[3][5] The term futyā refers to soliciting and issuing fatwas.[9]

Origins

The origins of muftis and the fatwa can be traced back to the Quran. On a number of occasions, the Quranic text instructs the Islamic prophet Muhammad how to respond to questions from his followers regarding religious and social practices. Several of these verses begin with the phrase "When they ask you concerning ..., say ..." In two cases (4:127, 4:176) this is expressed with verbal forms of the root f-t-y, which signify asking for or giving an authoritative answer. In the hadith literature, this three-way relationship between God, Muhammad, and believers, is typically replaced by a two-way consultation, in which Muhammad replies directly to queries from his Companions (sahaba).[10]

According to Islamic doctrine, with Muhammad's death in 632, God ceased to communicate with mankind through revelation and prophets. At that point, the rapidly expanding Muslim community turned to Muhammad's Companions, as the most authoritative voices among them, for religious guidance, and some of them are reported to have issued pronouncements on a wide range of subjects. The generation of Companions was in turn replaced in that role by the generation of Successors (tabi'un).[10] The institution of ifta thus developed in Islamic communities under a question-and-answer format for communicating religious knowledge, and took on its definitive form with development of the classical theory of Islamic law.[4] By the 8th century CE, muftis became recognized as legal experts who elaborated Islamic law and clarified its application to practical issues arising in the Islamic community.[2]

In pre-modern Islam

Mufti's activity (iftāʾ)

The legal theory of the ifta was formulated in the classical texts of usul al-fiqh (principles of jurisprudence), while more practical guidelines for muftis were found in manuals called adab al-mufti or adab al-fatwa (etiquette of the mufti/fatwa).[7]

A mufti's fatwa is issued in response to a query.[8] Fatwas can range from a simple yes/no answer to a book-length treatise.[3][5] A short fatwa may state a well-known point of law in response to a question from a lay person, while a "major" fatwa may give a judgment on an unprecedented case, detailing the legal reasoning behind the decision.[3][5] Queries to muftis were supposed to address real and not hypothetical situations and be formulated in general terms, leaving out names of places and people. Since a mufti was not supposed to inquire into the situation beyond the information included in the query, queries regarding contentious matters were often carefully constructed to elicit the desired response.[6] A mufti's understanding of the query commonly depended on their grasp of local customs and colloquial expressions. In theory, if the query was unclear or not sufficiently detailed for a ruling, the mufti was supposed to state these caveats in their response.[6] Muftis often consulted another mufti on difficult cases, though this practice was not foreseen by legal theory, which saw futya as a transaction between one qualified jurist and one "unqualified" petitioner.[11]

In theory, a mufti was expected to issue fatwas free of charge. In practice, muftis commonly received support from the public treasury, public endowments or private donations. Taking of bribes was forbidden.[10][6] Until the 11th or 12th century, the vast majority of jurists held other jobs to support themselves. These were generally lower- and middle-class professions such as tanning, manuscript copying or small trade.[12]

Role of muftis

The classical institution of ifta is similar to jus respondendi in Roman law and the responsa in Jewish law.[6][13]

Muftis have played three important roles in the classical legal system:

- managing information about Islam by providing legal advice to Muslim populations as well as counseling them in matters of ritual and ethics;[4][6]

- advising courts of law on finer points of Islamic law, in response to queries from judges;[4][5]

- elaborating substantive Islamic law, particularly though a genre of legal literature developed by author-jurists who collected fatwas of prominent muftis and integrated them into books.[4][6]

Islamic doctrine regards the practice of ifta as a collective obligation (farḍ al-kifāya), which must be discharged by some members of the community.[2] Before the rise of modern schools, the study of law was a centerpiece of advanced education in the Islamic world. A relatively small class of legal scholars controlled the interpretation of sharia on a wide range of questions essential to the society, ranging from ritual to finance. It was considered a requirement for qualified jurists to communicate their knowledge through teaching or issuing fatwas. The ideal mufti was conceived as an individual of scholarly accomplishments and exemplary morals, and muftis were generally approached with the respect and deference corresponding to these expectations.[6]

Judges generally sought an opinion from a mufti with higher scholarly authority than themselves for difficult cases or potentially controversial verdicts.[3][9] Fatwas were routinely upheld in courts, and if a fatwa was disregarded, it was usually because another fatwa supporting a different position was judged to be more convincing. If a party in a dispute was not able to obtain a fatwa supporting their position, they would be unlikely to pursue their case in court, opting for informal mediation instead, or abandoning their claim altogether.[14] Sometimes muftis could be petitioned for a fatwa relating to a court judgement that has already been passed, acting as an informal appeals process, but the extent of this practice and its mechanism varied across history.[15] While in most of the Islamic world judges were not required to consult muftis by any political authority, in Muslim Spain this practice was mandatory, so that a judicial decision was considered invalid without prior approval by a legal specialist.[16]

Author-jurists collected fatwas by muftis of high scholarly reputation and abstracted them into concise formulations of legal norms for the benefit of judges, giving a summary of jurisprudence for a particular madhhab (legal school).[4][14] Author-jurists sought out fatwas that reflected the social conditions of their time and place, often opting for later legal opinions which were at variance with the doctrine of early authorities.[14] Research by Wael Hallaq and Baber Johansen has shown that the rulings of muftis collected in these volumes could, and sometimes did, have a significant impact on the development of Islamic law.[2]

During the early centuries of Islam, the roles of mufti, author-jurist and judge were not mutually exclusive. A jurist could lead a teaching circle, conduct a fatwa session, and adjudicate court cases in a single day, devoting his night hours to writing a legal treatise. Those who were able to act in all four capacities were regarded as the most accomplished jurists.[12]

Qualifications of a mufti

The basic prerequisite for issuing fatwas under the classical legal theory was religious knowledge and piety. According to the adab al-mufti manuals, a mufti must be an adult, Muslim, trusted and reliable, of good character and sound mind, an alert and rigorous thinker, trained as a jurist, and not a sinner.[10] On a practical level, the stature of muftis derived from their reputation for scholarly expertise and upright character.[3] Issuing of fatwas was among the most demanding occupations in medieval Islam and muftis were among the best educated religious scholars of their time.[2]

According to legal theory, it was up to each mufti to decide when he was ready to practice. In practice, an aspiring jurist would normally study for several years with one or several recognized scholars, following a curriculum that included Arabic grammar, hadith, law and other religious sciences. The teacher would decide when the student was ready to issue fatwas by giving him a certificate (ijaza).[15]

During the first centuries of Islam, it was assumed that a mufti was a mujtahid, i.e., a jurist who is capable of deriving legal rulings directly from the scriptural sources through independent reasoning (ijtihad), evaluating the reliability of hadith and applying or even developing the appropriate legal methodologies. Starting from around 1200 CE, legal theorists began to accept that muftis of their time may not possess the knowledge and legal skill to perform this activity. In addition, it was felt that the major question of jurisprudence had already been addressed by master jurists of earlier times, so that later muftis only had to follow the legal opinions established within their legal school (taqlid). At that point, the notions of mufti and mujtahid became distinguished, and legal theorists classified jurists into three or more levels of competence.[17]

Unlike the post of qadi, which is reserved for men in the classical sharia system, fatwas could be issued by qualified women as well as men.[13] In practice, the vast majority of jurists who completed the lengthy curriculum in linguistic and religious sciences required to obtain the qualification to issue fatwas were men.[3] Slaves and persons who were blind or mute were likewise theoretically barred from the post of a judge, but not that of mufti.[10]

Mufti vs. judge

The mufti and the judge play different roles in the classical sharia system, with corresponding differences between a fatwa and a qada (court decision):

- A fatwa is nonbinding, while a court decision is binding and enforceable.[3][4]

- A fatwa may deal with rituals, ethical questions, religious doctrines and sometimes even philosophical issues, while court cases dealt with legal matters in the narrow sense.[4][3]

- The authority of a court judgment applies only to the specific court case, while a fatwa applies to all cases that fit the premises of the query.[6]

- A fatwa is made on the basis of information provided in the request, while a judge actively investigates the facts of the case.[3][6]

- A judge evaluates rival claims of two parties in a dispute in order to reach a verdict, while a fatwa is made on the basis of information provided by a single petitioner.[3][6]

- Fatwas by prominent jurists were collected in books as sources of precedent, while court decisions were entered into court registers, but not otherwise disseminated.[3][6]

- While both muftis and judges were interpreters of sharia, judicial interpretation centered on evaluating evidence such as testimony and oath, while a mufti investigated textual sources of law (scripture and legal literature).[6]

- In the classical legal system, judges were civil servants appointed by the ruler, while muftis were private scholars and not appointed officials.[8]

Institutions

.jpg.webp)

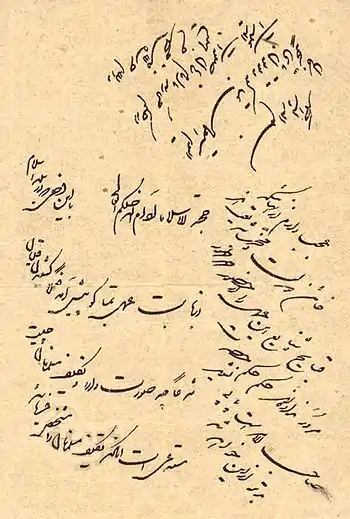

Before the 11th century CE, anyone who possessed scholarly recognition as an Islamic jurist could issue fatwas. Starting around that time, however, the public office of mufti began to appear alongside the private issuing of fatwas. In Khurasan, the rulers appointed a head of the local ulama, called shaykh al-Islam, who also functioned as the chief mufti. The Mamluks appointed four muftis, one for each of the four Sunni madhhabs, to the appeals courts of provincial capitals. The Ottomans organized muftis into a hierarchical bureaucracy with a chief mufti of the empire called shaykh al-islam at the top. The Ottoman shaykh al-Islam (Turkish: şeyhülislam), was among the most powerful state officials.[6] Scribes reviewed queries directed to Ottoman muftis and rewrote them to facilitate issuing of fatwas.[6][5] In Mughal India and Safavid Iran the chief mufti had the title of sadr.[5]

For the first few centuries of Islam, muftis were educated in informal study circles, but beginning in the 11th and 12th centuries, the ruling elites began to establish institutions of higher religious learning known as madrasas in an effort to secure support and cooperation of the ulema (religious scholars). Madrasas, which were primarily devoted to the study of law, soon multiplied throughout the Islamic world, helping to spread Islamic learning beyond urban centers and to unite diverse Islamic communities in a shared cultural project.[18]

In some states, such as Muslim Spain, muftis were assigned to courts in advisory roles. In Muslim Spain jurists also sat on a shura (council) advising the ruler. Muftis were additionally appointed to other public functions, such as market inspectors.[4]

In Shia Islam

While the office of the mufti was gradually subsumed into the state bureaucracy in much of the Sunni Muslim world, Shia religious establishment followed a different path in Iran starting from the early modern era. During Safavid rule, independent Islamic jurists (mujtahids) claimed the authority to represent the hidden imam. Under the usuli doctrine that prevailed among Twelver Shias in the 18th century and under the Qajar dynasty, the mujtahids further claimed to act collectively as deputies of the imam. According to this doctrine, all Muslims are supposed to follow a high-ranking living mujtahid bearing the title of marja' al-taqlid, whose fatwas are considered binding, unlike fatwas in Sunni Islam. Thus, in contrast to Sunni muftis, Shia mujtahids gradually achieved increasing independence from the state.[5]

Public and political fatwas

While most fatwas were delivered to an individual or a judge, some fatwas that were public or political in nature played an important role in religious legitimation, doctrinal disputes, political criticism, or political mobilization. As muftis were progressively incorporated into government bureaucracies in the course of Islamic history, they were often expected to support government policies. Ottoman sultans regularly sought fatwas from the chief mufti for administrative and military initiatives, including fatwas sanctioning jihad against Mamluk Egypt and Safavid Iran.[3] Fatwas by the Ottoman chief mufti were also solicited by the rulers to legitimize new social and economic practices, such as financial and penal laws enacted outside of sharia, printing of nonreligious books (1727) and vaccination (1845).[5]

At other times muftis wielded their influence independently of the ruler, and several Ottoman and Moroccan sultans were deposed by a fatwa.[3] This happened, for example, to the Ottoman sultan Murad V on the grounds of his insanity.[5] Public fatwas were also used to dispute doctrinal matters, and in some case to proclaim that certain groups or individuals who professed to be Muslim were to be excluded from the Islamic community (a practice known as takfir).[3] In both political and scholarly sphere, doctrinal controversies between different states, denominations or centers of learning were accompanied by dueling fatwas.[6] Muftis also acted to counteract the influence of judges and secular functionaries. By articulating grievances and legal rights of the population, public fatwas often prompted an otherwise unresponsive court system to provide redress.[5]

In the modern era

Modern institutions

_-_TIMEA.jpg.webp)

Under European colonial rule, the institution of dar al-ifta was established in a number of madrasas (law colleges) as a centralized place for issuing of fatwas, and these organizations to a considerable extent replaced independent muftis as religious guides for the general population.[6] Following independence, most Muslim states established national organizations devoted to issuing fatwas. One example is the Egyptian Dar al-Ifta, founded in 1895, which has served to articulate a national vision of Islam through fatwas issued in response to government and private queries.[5] National governments in Muslim-majority countries also instituted councils of senior religious scholars to advise the government on religious matters and issue fatwas. These councils generally form part of the ministry for religious affairs, rather than the justice department, which may have a more assertive attitude toward the executive branch.[4]

While chief muftis of earlier times oversaw a hierarchy of muftis and judges applying traditional jurisprudence, most modern states have adopted European-influenced legal codes and no longer employ traditional judicial procedures or traditionally trained judges. State muftis generally promote a vision of Islam that is compatible with state law of their country.[5]

Although some early theorists argued that muftis should not respond to questions on certain subjects, such as theology, muftis have in practice handled queries relating to a wide range of subjects. This trend continued in modern times, and contemporary state-appointed muftis and institutions for ifta respond to government and private queries on varied issues, including political conflicts, Islamic finance, and medical ethics, contributing to shaping a national Islamic identity.[3]

Muftis in modern times have increasingly relied on the process of ijtihad, i.e. deriving legal rulings based on an independent analysis rather than conformity with the opinions of earlier legal authorities (taqlid).[8] While in the past muftis were associated with a particular school of law (madhhab), in the 20th century many muftis began to assert their intellectual independence from traditional schools of jurisprudence.[6]

Modern media have facilitated cooperative forms to ifta. Networks of muftis are commonly engaged by fatwa websites, so that queries are distributed among the muftis in the network, who still act as individual jurisconsults. In other cases, Islamic jurists of different nationalities, schools of law, and sometimes even denominations (Sunni and Shia), coordinate to issue a joint fatwa, which is expected to command greater authority with the public than individual fatwas. The collective fatwa (sometimes called ijtihād jamāʿī, "collective legal interpretation") is a new historical development, and it is found in such settings as boards of Islamic financial institutions and international fatwa councils.[8]

There exists no international Islamic authority to settle differences in interpretation of Islamic law. An International Islamic Fiqh Academy was created by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, but its legal opinions are not binding.[4]

Role in politics

In the modern era, public "fatwa wars" have reflected political controversies in the Muslim world, from anti-colonial struggles to the Gulf War of the 1990s, when muftis in some countries issued fatwas supporting collaboration with the US-led coalition, while muftis from other countries endorsed the Iraqi call for jihad against the US and its collaborators.[19][7]

During the era of Western colonialism, some muftis issued fatwas seeking to mobilize popular resistance to foreign domination, while others were induced by colonial authorities to issue fatwas supporting accommodation with colonial rule. Muftis also intervened in the political process on many other occasions during the colonial era. For example, in 1904 a fatwa by Moroccan ulema achieved the dismissal of European experts hired by the state, while in 1907 another Moroccan fatwa succeeded in deposing the sultan for failing to defend the state against French aggression. The 1891 tobacco protest fatwa by the Iranian mujtahid Mirza Shirazi, which prohibited smoking as long as the British tobacco monopoly was in effect, also achieved its goals.[5]

Some muftis in the modern era, like the mufti of the Lebanese republic in the mid-20th century and the Grand Mufti of the Sultanate of Oman, were important political leaders.[6] In Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini used proclamations and fatwas to introduce and legitimize a number of institutions, including the Council of the Islamic Revolution and the Iranian Parliament.[5] Khomeini's most publicized fatwa was the proclamation condemning Salman Rushdie to death for his novel The Satanic Verses.[5]

Many militant and reform movements in modern times have disseminated fatwas issued by individuals who do not possess the qualifications traditionally required of a mufti. A famous example is the fatwa issued in 1998 by Osama Bin Laden and four of his associates, proclaiming "jihad against Jews and Crusaders" and calling for killing of American civilians. In addition to denouncing its content, many Islamic jurists stressed that bin Laden was not qualified to either issue a fatwa or declare a jihad.[5]

The Amman Message was a statement, signed in 2005 in Jordan by nearly 200 prominent Islamic jurists, which served as a "counter-fatwa" against a widespread use of takfir (excommunication) by jihadist groups to justify jihad against rulers of Muslim-majority countries. The Amman Message recognized eight legitimate schools of Islamic law and prohibited declarations of apostasy against them. The statement also asserted that fatwas can be issued only by properly trained muftis, thereby seeking to delegitimize fatwas issued by militants who lack the requisite qualifications.[3][5]

Erroneous and sometimes bizarre fatwas issued by unqualified or eccentric individuals acting as muftis has at times given rise to complaints about a "chaos" in the modern practice of ifta.[7]

Role in society

Advances in print media and the rise of the internet have changed the role played by muftis in modern society.[5] In the pre-modern era, most fatwas issued in response to private queries were read only by the petitioner. Early in the 20th century, the reformist Islamic scholar Rashid Rida responded to thousands of queries from around the Muslim world on a variety of social and political topics in the regular fatwa section of his Cairo-based journal Al-Manar.[7][6] In the late 20th century, when the Grand Mufti of Egypt Sayyid Tantawy issued a fatwa allowing interest banking, the ruling was vigorously debated in the Egyptian press by both religious scholars and lay intellectuals.[5]

In the internet age, a large number of websites has appeared offering fatwas to readers around the world. For example, IslamOnline publishes an archive of "live fatwa" sessions, whose number approached a thousand by 2007, along with biographies of the muftis. Together muftis who issue call-in fatwas during radio shows and satellite television programs, these sites have contributed to the rise of new forms of contemporary ifta.[5] Unlike the concise or technical pre-modern fatwas, fatwas delivered through modern mass media often seek to be more expansive and accessible to the wide public.[7]

As the influence of muftis in the courtroom has declined in modern times, there has been a relative increase in the proportion of fatwas dealing with rituals and further expansion in purely religious areas like Quranic exegesis, creed, and Sufism. Modern muftis issue fatwas on topics as diverse as insurance, sex-change operations, moon exploration and beer drinking.[19] In the private sphere, some muftis have begun to resemble social workers, giving advice on various personal issues encountered in everyday life.[7] The vast amount of fatwas produced in the modern world attests to the importance of Islamic authenticity to many Muslims. However, there is little research available to indicate to what extent Muslims acknowledge the authority of muftis and heed their rulings in real life.[8]

See also

References

Citations

- Nanji 2009.

- Swartz 2009.

- Hendrickson 2013.

- Masud & Kéchichian 2009.

- Dallal & Hendrickson 2009.

- Messick & Kéchichian 2009.

- Messick 2017.

- Berger 2014.

- Vikør 2005, p. 143.

- Powers 2017.

- Vikør 2005, p. 147.

- Hallaq 2009, p. 13.

- Tyan & Walsh 2012.

- Hallaq 2009, pp. 9–11.

- Vikør 2005, p. 144.

- Hallaq 2010, p. 159.

- Vikør 2005, pp. 152–154.

- Berkey 2004.

- Gräf 2017.

Sources

- Berger, Maurits S. (2014). "Fatwa". In Emad El-Din Shahin (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berkey, Jonathan (2004). "Education". In Richard C. Martin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference USA.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dallal, Ahmad S.; Hendrickson, Jocelyn (2009). "Fatwā. Modern usage". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gräf, Bettina (2017). "Fatwā, modern media". In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hallaq, Wael B. (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hallaq, Wael B. (2010). "Islamic Law: History and Transformation". In Robert Irwin (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam. Volume 4: Islamic Cultures and Societies to the End of the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hendrickson, Jocelyn (2009). "Law. Minority Jurisprudence". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hendrickson, Jocelyn (2013). "Fatwa". In Gerhard Böwering, Patricia Crone (ed.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Masud, Muhammad Khalid; Kéchichian, Joseph A. (2009). "Fatwā. Concepts of Fatwā". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Messick, Brinkley; Kéchichian, Joseph A. (2009). "Fatwā. Process and Function". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Messick, Brinkley (2017). "Fatwā, modern". In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27049.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nanji, Azim A. (2009). "Muftī". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Powers, David S. (2017). "Fatwā, premodern". In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27048.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swartz, Merlin (2009). "Mufti". In Stanley N. Katz (ed.). The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Legal History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tyan, E.; Walsh, J.R. (2012). "Fatwā". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0219.

- Vikør, Knut S. (2005). Between God and the Sultan: A History of Islamic Law. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Look up mufti in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Fatwa – multi-part article from The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, via Oxford Islamic Studies

- The ethics of Muftī by Imam Ibn Khaldûn(in French)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.