Multivalued function

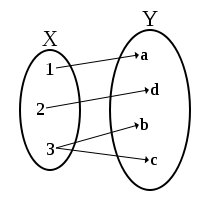

In mathematics, a multivalued function, also called multifunction, many-valued function, set-valued function, is similar to a function, but may associate several values to each input. More precisely, a multivalued function from a domain X to a codomain Y associates each x in X to one or more values y in Y; it is thus a serial binary relation. Some authors allow a multivalued function to have no value for some inputs (in this case a multivalued function is simply a binary relation).

| Function |

|---|

| x ↦ f (x) |

| Examples by domain and codomain |

| Classes/properties |

| Constructions |

| Generalizations |

However, in some contexts such as in complex analysis (X = Y = ℂ), authors prefer to mimic function theory as they extend concepts of the ordinary (single-valued) functions. In this context, an ordinary function is often called a single-valued function to avoid confusion.

The term multivalued function originated in complex analysis, from analytic continuation. It often occurs that one knows the value of a complex analytic function in some neighbourhood of a point . This is the case for functions defined by the implicit function theorem or by a Taylor series around . In such a situation, one may extend the domain of the single-valued function along curves in the complex plane starting at . In doing so, one finds that the value of the extended function at a point depends on the chosen curve from to ; since none of the new values is more natural than the others, all of them are incorporated into a multivalued function. For example, let be the usual square root function on positive real numbers. One may extend its domain to a neighbourhood of in the complex plane, and then further along curves starting at , so that the values along a given curve vary continuously from . Extending to negative real numbers, one gets two opposite values of the square root such as , depending on whether the domain has been extended through the upper or the lower half of the complex plane. This phenomenon is very frequent, occurring for nth roots, logarithms, and inverse trigonometric functions.

To define a single-valued function from a complex multivalued function, one may distinguish one of the multiple values as the principal value, producing a single-valued function on the whole plane which is discontinuous along certain boundary curves. Alternatively, dealing with the multivalued function allows having something that is everywhere continuous, at the cost of possible value changes when one follows a closed path (monodromy). These problems are resolved in the theory of Riemann surfaces: to consider a multivalued function as an ordinary function without discarding any values, one multiplies the domain into a many-layered covering space, a manifold which is the Riemann surface associated to .

Examples

- Every real number greater than zero has two real square roots, so that square root may be considered a multivalued function. For example, we may write ; although zero has only one square root, .

- Each nonzero complex number has two square roots, three cube roots, and in general n nth roots. The only nth root of 0 is 0.

- The complex logarithm function is multiple-valued. The values assumed by for real numbers and are for all integers .

- Inverse trigonometric functions are multiple-valued because trigonometric functions are periodic. We have

- As a consequence, arctan(1) is intuitively related to several values: π/4, 5π/4, −3π/4, and so on. We can treat arctan as a single-valued function by restricting the domain of tan x to −π/2 < x < π/2 – a domain over which tan x is monotonically increasing. Thus, the range of arctan(x) becomes −π/2 < y < π/2. These values from a restricted domain are called principal values.

- The indefinite integral can be considered as a multivalued function. The indefinite integral of a function is the set of functions whose derivative is that function. The constant of integration follows from the fact that the derivative of a constant function is 0.

- The argmax is multivalued, for example

These are all examples of multivalued functions that come about from non-injective functions. Since the original functions do not preserve all the information of their inputs, they are not reversible. Often, the restriction of a multivalued function is a partial inverse of the original function.

Multivalued functions of a complex variable have branch points. For example, for the nth root and logarithm functions, 0 is a branch point; for the arctangent function, the imaginary units i and −i are branch points. Using the branch points, these functions may be redefined to be single-valued functions, by restricting the range. A suitable interval may be found through use of a branch cut, a kind of curve that connects pairs of branch points, thus reducing the multilayered Riemann surface of the function to a single layer. As in the case with real functions, the restricted range may be called the principal branch of the function.

Set-valued analysis

Set-valued analysis is the study of sets in the spirit of mathematical analysis and general topology.

Instead of considering collections of only points, set-valued analysis considers collections of sets. If a collection of sets is endowed with a topology, or inherits an appropriate topology from an underlying topological space, then the convergence of sets can be studied.

Much of set-valued analysis arose through the study of mathematical economics and optimal control, partly as a generalization of convex analysis; the term "variational analysis" is used by authors such as R. Tyrrell Rockafellar and Roger J-B Wets, Jonathan Borwein and Adrian Lewis, and Boris Mordukhovich. In optimization theory, the convergence of approximating subdifferentials to a subdifferential is important in understanding necessary or sufficient conditions for any minimizing point.

There exist set-valued extensions of the following concepts from point-valued analysis: continuity, differentiation, integration,[1] implicit function theorem, contraction mappings, measure theory, fixed-point theorems,[2] optimization, and topological degree theory.

Equations are generalized to inclusions.

Types of multivalued functions

One can distinguish multiple concepts generalizing continuity, such as the closed graph property and upper and lower hemicontinuity[lower-alpha 1]. There are also various generalizations of measure to multifunctions.

Applications

Multifunctions arise in optimal control theory, especially differential inclusions and related subjects as game theory, where the Kakutani fixed-point theorem for multifunctions has been applied to prove existence of Nash equilibria (in the context of game theory, a multivalued function is usually referred to as a correspondence). This among many other properties loosely associated with approximability of upper hemicontinuous multifunctions via continuous functions explains why upper hemicontinuity is more preferred than lower hemicontinuity.

Nevertheless, lower semi-continuous multifunctions usually possess continuous selections as stated in the Michael selection theorem, which provides another characterisation of paracompact spaces.[3][4] Other selection theorems, like Bressan-Colombo directional continuous selection, Kuratowski and Ryll-Nardzewski measurable selection theorem, Aumann measurable selection, and Fryszkowski selection for decomposable maps are important in optimal control and the theory of differential inclusions.

In physics, multivalued functions play an increasingly important role. They form the mathematical basis for Dirac's magnetic monopoles, for the theory of defects in crystals and the resulting plasticity of materials, for vortices in superfluids and superconductors, and for phase transitions in these systems, for instance melting and quark confinement. They are the origin of gauge field structures in many branches of physics.

Contrast with

See also

- Fat link, a one-to-many hyperlink

- Interval finite element

- Partial function

References

- Aumann, Robert J. (1965). "Integrals of Set-Valued Functions". Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications. 12 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/0022-247X(65)90049-1.

- Kakutani, Shizuo (1941). "A generalization of Brouwer's fixed point theorem". Duke Mathematical Journal. 8 (3): 457–459. doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-41-00838-4.

- Ernest Michael (Mar 1956). "Continuous Selections. I" (PDF). Annals of Mathematics. Second Series. 63 (2): 361–382. doi:10.2307/1969615. hdl:10338.dmlcz/119700. JSTOR 1969615.

- Dušan Repovš; P.V. Semenov (2008). "Ernest Michael and theory of continuous selections". Topology Appl. 155 (8): 755–763. arXiv:0803.4473. doi:10.1016/j.topol.2006.06.011.

Notes

- Some authors use the term ‘semicontinuous’ instead of ‘hemicontinuous’.

Further reading

- C. D. Aliprantis and K. C. Border, Infinite dimensional analysis. Hitchhiker's guide, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2006

- J. Andres and L. Górniewicz, Topological Fixed Point Principles for Boundary Value Problems, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003

- J.-P. Aubin and A. Cellina, Differential Inclusions, Set-Valued Maps And Viability Theory, Grundl. der Math. Wiss. 264, Springer - Verlag, Berlin, 1984

- J.-P. Aubin and H. Frankowska, Set-Valued Analysis, Birkhäuser, Basel, 1990

- K. Deimling, Multivalued Differential Equations, Walter de Gruyter, 1992

- Geletu, A. (2006). "Introduction to Topological Spaces and Set-Valued Maps" (PDF). Lecture notes. Technische Universität Ilmenau.

- H. Kleinert, Multivalued Fields in Condensed Matter, Electrodynamics, and Gravitation, World Scientific (Singapore, 2008) (also available online)

- H. Kleinert, Gauge Fields in Condensed Matter, Vol. I: Superflow and Vortex Lines, 1–742, Vol. II: Stresses and Defects, 743–1456, World Scientific, Singapore, 1989 (also available online: Vol. I and Vol. II)

- D. Repovš and P.V. Semenov, Continuous Selections of Multivalued Mappings, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht 1998

- E. U. Tarafdar and M. S. R. Chowdhury, Topological methods for set-valued nonlinear analysis, World Scientific, Singapore, 2008

- Mitroi, F.-C.; Nikodem, K.; Wąsowicz, S. (2013). "Hermite-Hadamard inequalities for convex set-valued functions". Demonstratio Mathematica. 46 (4): 655–662. doi:10.1515/dema-2013-0483.