Myeloproliferative neoplasm

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of rare blood cancers in which excess red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets are produced in the bone marrow. Myelo refers to the bone marrow, proliferative describes the rapid growth of blood cells and neoplasm describes that growth as abnormal and uncontrolled.

| Myeloproliferative neoplasm | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Myeloproliferative diseases (MPDs) |

| |

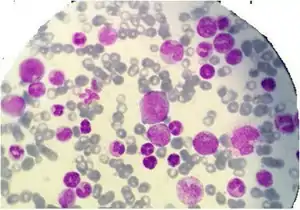

| Myelogram of someone with a myeloproliferative disorder. | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

The overproduction of blood cells is often associated with a somatic mutation, for example in the JAK2, CALR, TET2, and MPL gene markers.

In rare cases, some MPNs such as primary myelofibrosis may accelerate and turn into acute myeloid leukemia.[1]

Classification

MPNs are classified as blood cancers by most institutions and organizations.[2] In MPNs, the neoplasm (abnormal growth) starts out as benign and can later become malignant.

As of 2016, the World Health Organization lists the following subcategories of MPNs:[3]

- Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

- Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL)

- Polycythemia vera (PV)

- Primary myelofibrosis (PMF)

- Essential thrombocythemia (ET)

- Chronic eosinophilic leukemia (not otherwise specified)

- MPN, unclassifiable (MPN-U)

Causes

MPNs arise when precursor cells (blast cells) of the myeloid lineages in the bone marrow develop somatic mutations which cause them to grow abnormally. There is a similar category of disease for the lymphoid lineage, the lymphoproliferative disorders acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphomas, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma.

Diagnosis

People with MPNs might not have symptoms when their disease is first detected via blood tests.[4] Depending on the nature of the myeloproliferative neoplasm, diagnostic tests may include red cell mass determination (for polycythemia), bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy, arterial oxygen saturation and carboxyhaemoglobin level, neutrophil alkaline phosphatase level, vitamin B12 (or B12 binding capacity), serum urate[5] or direct sequencing of the patient's DNA.[6] According to WHO diagnostic criteria published in 2016, myeloproliferative neoplasms are diagnosed as follows:[7]

- Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has a presence of the hallmark Philadelphia Chromosome (BCR-ABL1) mutation.

- Chronic neutrophilic leukemia

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is characterized by a mutation in the CSF3R gene and an exclusion of other causes of neutrophilia.

- Essential thrombocythemia

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is diagnosed with a platelet count greater than 450 × 109/L and is associated with the JAK2 V617F mutation in up to 55% of cases[8] and with an MPL (thrombopoietin receptor) mutation in up to 5% of cases:.[9] There should be no increase in reticulin fibers and the patient should not meet the criteria for other MPNs, in particular Pre-PMF.

- Polycythemia vera

Polycythemia vera (PV) is associated most often with the JAK2 V617F mutation in greater than 95% of cases, whereas the remainder have a JAK2 exon 12 mutation. High hemoglobin or hematocrit counts are required, as is a bone marrow examination showing "prominent erythroid, granulocytic and megakaryocytic proliferation with pleomorphic, mature megakaryocytes."

- Prefibrotic/early primary myelofibrosis

Prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis (Pre-PMF) is typically associated with JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutations and shows a reticulin fibrosis no greater than grade 1. Anemia, splenomegaly, LDH above the upper limits and leukocytosis are minor criteria.

- Overtly fibrotic myelofibrosis

Like pre-PMF, overt primary myelofibrosis is associated with JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutations. However, a bone marrow biopsy will show reticulin and/or collagen fibrosis with a grade 2 or 3. Anemia, splenomegaly, LDH above the upper limits and leukocytosis are minor criteria.

- MPN-U

Patients with otherwise unexplained thrombosis and with neoplasms that can't be classified in one of the other categories.

Treatment

No curative drug treatment exists for MPNs.[10] Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can be a curative treatment for a small group of patients, however MPN treatment is typically focused on symptom control and myelosuppressive drugs to help control the production of blood cells.

The goal of treatment for ET and PV is prevention of thrombohemorrhagic complications. The goal of treatment for MF is amelioration of anemia, splenomegaly, and other symptoms. Low-dose aspirin is effective in PV and ET. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors like imatinib have improved the prognosis of CML patients to near-normal life expectancy.[11]

Recently, a JAK2 inhibitor, namely ruxolitinib, has been approved for use in primary myelofibrosis.[12] Trials of these inhibitors are in progress for the treatment of the other myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Incidence

Although considered rare diseases, incidence rates of MPNs are increasing, in some cases tripling. It is hypothesized that the increase may be related to improved diagnostic abilities from the identification of the JAK2 and other gene markers, as well as continued refinement of the WHO guidelines.[13]

There is wide variation in reported MPN incidence and prevalence worldwide, with a publication bias suspected for essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis.[14]

History

The concept of myeloproliferative disease was first proposed in 1951 by the hematologist William Dameshek.[15] The discovery of the association of MPNs with the JAK2 gene marker in 2005 and the CALR marker in 2013 improved the ability to classify MPNs.[16]

MPNs were classified as blood cancers by the World Health Organization in 2008.[17] Previously, they were known as myeloproliferative diseases (MPD).

In 2016, Mastocytosis was no longer classified as an MPN.[18]

References

- "Preventing Myelofibrosis from Progressing to Acute Myeloid Leukemia". Cure Today. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- "Are Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs) Cancer?". #MPNresearchFoundation. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- Arber, Daniel A.; Orazi, Attilio; Hasserjian, Robert; Thiele, Jürgen; Borowitz, Michael J.; Le Beau, Michelle M.; Bloomfield, Clara D.; Cazzola, Mario; Vardiman, James W. (2016-05-19). "The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia". Blood. 127 (20): 2391–2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 27069254.

- "Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Risk Factors | Seattle Cancer Care Alliance". www.seattlecca.org. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- Levene, Malcolm I.; Lewis, S. M.; Bain, Barbara J.; Imelda Bates (2001). Dacie & Lewis Practical Haematology. London: W B Saunders. p. 586. ISBN 0-443-06377-X.

- Magor GW, Tallack MR, Klose NM, Taylor D, Korbie D, Mollee P, Trau M, Perkins AC (September 2016). "Rapid Molecular Profiling of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Using Targeted Exon Resequencing of 86 Genes Involved in JAK-STAT Signaling and Epigenetic Regulation". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 18 (5): 707–718. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.05.006. PMID 27449473.

- Barbui, Tiziano; Thiele, Jürgen; Gisslinger, Heinz; Kvasnicka, Hans Michael; Vannucchi, Alessandro M.; Guglielmelli, Paola; Orazi, Attilio; Tefferi, Ayalew (2018-02-09). "The 2016 WHO classification and diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms: document summary and in-depth discussion". Blood Cancer Journal. 8 (2): 15. doi:10.1038/s41408-018-0054-y. ISSN 2044-5385. PMC 5807384. PMID 29426921.

- Campbell PJ, Scott LM, Buck G, Wheatley K, East CL, Marsden JT, et al. (December 2005). "Definition of subtypes of essential thrombocythaemia and relation to polycythaemia vera based on JAK2 V617F mutation status: a prospective study". Lancet. 366 (9501): 1945–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67785-9. PMID 16325696. S2CID 36419846.

- Beer PA, Campbell PJ, Scott LM, Bench AJ, Erber WN, Bareford D, et al. (July 2008). "MPL mutations in myeloproliferative disorders: analysis of the PT-1 cohort". Blood. 112 (1): 141–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-01-131664. PMID 18451306.

- "MPN summary".

- Tefferi, Ayalew; Vainchenker, William (2011-01-10). "Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Molecular Pathophysiology, Essential Clinical Understanding, and Treatment Strategies". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (5): 573–582. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8711. ISSN 0732-183X. PMID 21220604.

- Tibes R, Bogenberger JM, Benson KL, Mesa RA (October 2012). "Current outlook on molecular pathogenesis and treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 16 (5): 269–83. doi:10.1007/s40291-012-0006-3. PMID 23023734. S2CID 16010648.

- Roaldsnes, Christina; Holst, René; Frederiksen, Henrik; Ghanima, Waleed (2017). "Myeloproliferative neoplasms: trends in incidence, prevalence and survival in Norway". European Journal of Haematology. 98 (1): 85–93. doi:10.1111/ejh.12788. ISSN 1600-0609. PMID 27500783. S2CID 19156436.

- Titmarsh, Glen J.; Duncombe, Andrew S.; McMullin, Mary Frances; O'Rorke, Michael; Mesa, Ruben; De Vocht, Frank; Horan, Sarah; Fritschi, Lin; Clarke, Mike; Anderson, Lesley A. (June 2014). "How common are myeloproliferative neoplasms? A systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Hematology. 89 (6): 581–587. doi:10.1002/ajh.23690. ISSN 1096-8652. PMID 24971434.

- Dameshek W (April 1951). "Some speculations on the myeloproliferative syndromes". Blood. 6 (4): 372–5. doi:10.1182/blood.V6.4.372.372. PMID 14820991.

- "Understanding MPNs- Overview | MPNRF". #MPNresearchFoundation. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- "What are Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs)?".

- Barbui T, Thiele J, Gisslinger H, Kvasnicka HM, Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P, et al. (February 2018). "The 2016 WHO classification and diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms: document summary and in-depth discussion". Blood Cancer Journal. 8 (2): 15. doi:10.1038/s41408-018-0054-y. PMC 5807384. PMID 29426921.

External links

- Myeloproliferative+Disorders at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- MPN Info via Cancer.gov

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |