Namaqua Fossil Forest Marine Protected Area

The Namaqua Fossil Forest Marine Protected Area is an offshore conservation region in the territorial waters/exclusive economic zone of South Africa

| Namaqua Fossil Forest Marine Protected Area | |

|---|---|

Namaqua Fossil Forest MPA location | |

| Location | Off the coast of Namaqualand, South Africa |

| Nearest city | Kleinsee |

| Coordinates | 29°31.5′S 16°40.8′E |

| Area | 1,200 km2 (460 sq mi) |

| Established | 2019 |

History

This area was above sea level a hundred million years ago, and was covered by temperate forests of trees related to the yellowwoods. Fossil tree trunks from some of these trees were seen from the submersible "JAGO" during explorations off Kleinsee in 1997. In 2014 the area was recognised as an ecologically and biologically significant area of global importance.[1]

Purpose

A marine protected area is defined by the IUCN as "A clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values".[2]

This MPA is specifically intended to protect the fossil forest.[3][1]

Extent

The MPA is about 15 nautical miles offshore west of Namaqualand, Northern Cape, between Kleinsee and Port Nolloth, in the 120 to 150 m depth range.[1] Area of sea protected by the MPA is 1200 km2[1]

Boundaries

The MPA boundaries are:[4]

- Northern boundary: S29°23', E16°36.6' to S29°23', E16°45'

- Eastern boundary: S29°23', E16°45' to S29°40', E16°45'

- Southern boundary: S29°40', E16°45' to S29°40', E16°36.6'

- Western boundary: S29°40', E16°36.6' to S29°23', E16°36.6'

Zonation

The MPA is zoned as a single controlled zone.[4]

Management

The marine protected areas of South Africa are the responsibility of the national government, which has management agreements with a variety of MPA management authorities, which manage the MPAs with funding from the SA Government through the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA).[2]

The Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries is responsible for issuing permits, quotas and law enforcement.[5]

Use

Geography

The known extent of the fossil forest is an outcrop of fossilized yellowwood trees on the seabed of about 2 km2 The depth range is 136–140 m. It is likely that this feature is significantly larger. The fossil tree trunks have been colonized by fragile scleractinian corals, confirmed by images from submersible surveys. The site has not yet been mined, but may be inside a current diamond mining lease area. Hard grounds north of known fossil forest may also be part of this feature.[3]

Climate

Ecology

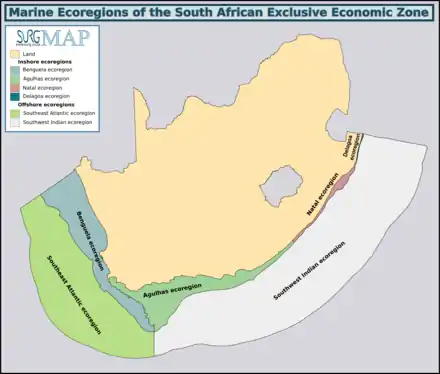

(describe position, biodiversity and endemism of the region) The MPA is in the warm temperate Benguela ecoregion to the west of Cape Point which extends northwards to the Orange River. There are some species endemic to South Africa along this coastline.[6]

(check below for applicability) Three major habitats exist in the sea in this region, two of them distinguished by the nature of the substrate. The substrate, or base material, is important in that it provides a base to which an organism can anchor itself, which is vitally important for those organisms which need to stay in one particular kind of place. Rocky shores and reefs provide a firm fixed substrate for the attachment of plants and animals. Sedimentary bottoms are a relatively unstable substrate and cannot anchor many of the larger benthic organisms. Finally there is open water, above the substrate and clear of the kelp forest, where the organisms must drift or swim. Mixed habitats are also frequently found, which are a combination of those mentioned above.[7] There are no significant estuarine habitats in the MPA.

Rocky reefs There are rocky reefs and mixed rocky and sandy bottoms. For many marine organisms the substrate is another type of marine organism, and it is common for several layers to co-exist.[7]:Ch.2

The type of rock of the reef is of some importance, as it influences the range of possibilities for the local topography, which in turn influences the range of habitats provided, and therefore the diversity of inhabitants. Sandstone and other sedimentary rocks erode and weather very differently, and depending on the direction of dip and strike, and steepness of the dip, may produce reefs which are relatively flat to very high profile and full of small crevices. These features may be at varying angles to the shoreline and wave fronts. There are fewer large holes, tunnels and crevices in sandstone reefs, but often many deep but low near-horizontal crevices.

Sedimentary bottoms (including silt, mud, sand, shelly, pebble and gravel bottoms) Sedimentary bottoms at first glance appear to be fairly barren areas, as they lack the stability to support many of the spectacular reef based species, and the variety of large organisms is relatively low. The sediment can be moved around by water action, to a greater or lesser degree depending on weather conditions and exposure of the area. This means that sessile organisms must be specifically adapted to areas of relatively loose substrate to thrive in them, and the variety of species found on a sedimentary bottom will depend on all these factors. Unconsolidated sedimentary bottoms have one important compensation for their instability, animals can burrow into the sand and move up and down within its layers, which can provide feeding opportunities and protection from predation. Other species can dig themselves holes in which to shelter, or may feed by filtering water drawn through the tunnel, or by extending body parts adapted to this function into the water above the sand.[7]:Ch.3

The open sea The pelagic water column is the major part of the living space at sea. This is the water between the surface and the top of the benthic zone, where living organisms swim, float or drift, and the food chain starts with phytoplankton, the mostly microscopic photosynthetic organisms that convert the energy of sunlight into organic material which feeds nearly everything else, directly or indirectly. In temperate seas there are distinct seasonal cycles of phytoplankton growth, based on the available nutrients and the available sunlight. Either can be a limiting factor. Phytoplankton tend to thrive where there is plenty of light, and they themselves are a major factor in restricting light penetration to greater depths, so the photosynthetic zone tends to be shallower in areas of high productivity.[7]:Ch.6 Zooplankton feed on the phytoplankton, and are in turn eaten by larger animals. The larger pelagic animals are generally faster moving and more mobile, giving them the option of changing depth to feed or to avoid predation, and to move to other places in search of a better food supply.

Marine species diversity

As of 2014, little is known about the ecology and biodiversity of the MPA. There are habitat forming corals and a newly described (2017) habitat-forming sponge is present in the area..[3]

Endemism

The MPA is in the cool temperate Benguela ecoregion to the west of Cape Point which extends northwards to the Orange River. There are species endemic to South Africa along this coastline.[6]

See also

References

- "Namaqua Fossil Forest MPA". www.marineprotectedareas.org.za. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Marine Protected Areas". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "EBSA Description: Namaqua Fossil Forest: General information - Summary". www.benguelacc.org. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Draft Regulations for the management of the Agulhas Front Complex Marine Protected Area" (PDF). Regulation Gazette No. 10553. Pretoria: Government Printer. 608 No.39646. 3 February 2016.

- "Marine Protected Area". Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Sink, K.; Harris, J.; Lombard, A. (October 2004). Appendix 1. South African marine bioregions (PDF). South African National Spatial Biodiversity Assessment 2004: Technical Report Vol. 4 Marine Component DRAFT (Report). pp. 97–109.

- Branch, G.M.; Branch, M.L. (1985). The Living Shores of Southern Africa (3rd impression ed.). Cape Town: C. Struik. ISBN 0 86977 115 9.