Nanjing decade

The Nanjing decade (also Nanking decade, Chinese: 南京十年 Nánjīng shí nián, or The Golden decade, Chinese: 黃金十年 Huángjīn shí nián) is an informal name for the decade from 1927 (or 1928) to 1937 in the Republic of China. It began when Nationalist Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek took Nanjing from Zhili clique warlord Sun Chuanfang halfway through the Northern Expedition in 1927. Chiang declared it to be the national capital despite the existence of a left-wing Nationalist government in Wuhan. The Wuhan faction gave in and the Northern Expedition continued until the Beiyang government in Beijing was overthrown in 1928. The decade ended with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and the retreat of the Nationalist government to Wuhan. GDP growth averaged 3.9 per cent a year from 1929 to 1941 and per capita GDP about 1.8 per cent.[1]

.gif)

Nanjing was of symbolic and strategic importance. The Ming dynasty had made Nanjing a capital, the republic had been established there in 1912, and Sun Yat-sen's provisional government had been there. Sun's body was brought and placed in a grand mausoleum to cement Chiang's legitimacy. Chiang was born in the neighboring province and the general area had strong popular support for him.

The Nanjing decade was marked by both progress and frustration. The period was far more stable than the preceding Warlord Era. There was enough stability to allow economic growth and the start of ambitious government projects, some of which were taken up again by the new government of the People's Republic after 1949. Nationalist foreign service officers negotiated diplomatic recognition from western governments and began to unravel the unequal treaties. Entrepreneurs, educators, lawyers, doctors, and other professionals were more free to create modern institutions than at any earlier time. Yet there was also government suppression of dissent, corruption and nepotism, revolt of several provinces, conflict within the government, the survival and growth of the Chinese Communist Party, and widespread protest against the government's failure to stop Japanese aggression.

The party-state

The organization and function of the KMT one-party state was derived from Sun's "Three Stages of Revolution" and his policy of Dang Guo. The first stage was military unification, which was carried out with the Northern Expedition. The second was "political tutelage" which was a provisional government led by the KMT to educate people about their political and civil rights, and the third stage was constitutional government. The KMT considered themselves to be at the second stage in 1928.

The KMT set up its five-branch government (based on the Three Principles of the People) using an organic law. This government disavowed continuity with the defunct Beiyang government that enjoyed international recognition; however the state was still the same – the Republic of China. Nevertheless, many bureaucrats from the Beiyang government flooded into Nanjing to receive jobs.

Chiang was elected President of the National Government by the KMT central executive committee in October 1928. In the absence of a National Assembly, the KMT's party congress functioned in its place. Since party membership was a requirement for civil service positions, the KMT was full of careerists and opportunists.

The KMT was heavily factionalized into pro- and anti-Chiang groups. The largest faction in the party following reunification was the pro-Chiang Whampoa clique (a.k.a. the National Revolutionary Army First Army Group/Central Army), which made up slightly over half of the party membership. A Whampoa sub-faction was the infamous Blue Shirts Society. Next was the CC Clique, a pro-Chiang civilian group. A third group, the technocratic Political Study Clique, was more liberal than the other two pro-Chiang factions. They were formed by KMT members of the first National Assembly back in 1916. These three factions competed with each other for Chiang's favor.

Opposition to Chiang came from both the left and the right. The leftist opposition was led by Wang Jingwei and known as the Reorganizationists. The rightist opposition was led by Hu Hanmin. Hu never created or joined a faction but he was viewed as the spiritual leader by the Western Hills Group, led by Lin Sen. There were also individuals within the party who were not part of any faction, like Sun Fo. These anti-Chiang figures were outnumbered in the party but held great power by their seniority, unlike many pro-Chiang cadres that joined only during or after the Northern Expedition. Chiang cleverly played these factions off against one another. The party itself was reduced to a mere propaganda machine, while real power laid with Chiang and the National Revolutionary Army (NRA).

Intra-party struggles

In 1922, the KMT had formed the First United Front with the Communists to defeat the warlords and reunify China. In April 1927, however, Chiang split with the Communists and purged them from the Front against the wishes of the KMT leadership in Wuhan, setting up a rival KMT government in Nanjing. The split and the purge was detrimental to the KMT's Northern Expedition and allowed the Zhili-Fengtian coalition to launch a successful counterattack. The mostly leftist Wuhan faction soon purged the Communists as well and reunited with Chiang in Nanjing. The Northern Expedition restarted in February 1928 and successfully reunited China by the end of the year.

At the end of the Expedition, the NRA consisted of four army groups: Chiang's Whampoa clique, Feng Yuxiang's Guominjun, Yan Xishan's Shanxi clique, and Li Zongren's New Guangxi clique. Chiang did not have direct control of the other three so he considered them to be threats.

In February 1929, Li Zongren fired the pro-Chiang governor of Hunan but Chiang objected and the two clashed in March, leading to Li's defeat and (temporary) expulsion from the KMT by the third party congress. Feng Yuxiang rebelled on May 19 but was humiliated when half of his army defected through bribery. From October to February, fighting resumed with Wang Jingwei and Lin Sen joining the opposition. In May 1930, the Central Plains War erupted, pitting Chiang against the Beiping faction of Yan Xishan, Feng Yuxiang, Li Zongren, and Wang Jingwei. Though victorious, Chiang's government was bankrupted.

In 1931, Hu Hanmin attempted to block Chiang's provisional constitution and was put under house arrest. This caused another uprising by Chen Jitang, Li Zongren, Sun Fo and other anti-Chiang factions who converged on Guangzhou to set up a rival government. War was averted due to the Japanese invasion of Manchuria but it did cause Chiang to release Hu and resign as president and premier. Chiang's influence was restored when he was made chairman of the Military Affairs Commission at the start of the Battle of Shanghai (1932). Hu moved to Guangzhou and led an autonomous government in Liangguang.

In November 1933, the Fujian Rebellion erupted by dissident KMT elements. The rebellion was crushed in January.

During Chiang's second premiership, Hu Hanmin died on 12 May 1936 and left a power vacuum in the south. Chiang wanted to fill it with a loyalist that would end the south's autonomy. Chen Jitang and Li Zongren conspired to overthrow Chiang but were politically outmaneuvered by bribes and defections. Chen resigned and the plot fizzled. In December, Chiang was kidnapped by Zhang Xueliang and forced to ally with the Communists in the Second United Front to combat the Japanese occupation.

In addition, the Ma clique and the Xinjiang clique, both KMT affiliates, were contesting each other in the western fringes from 1931 until 1937 in the Xinjiang Wars when the Soviet Union's support helped the Xinjiang group to triumph. Xinjiang then became a Soviet protectorate and safe haven for Communists. The Ma clique also fought Sun Dianying in 1934.

Wang Jingwei's collaborationist government during the Second Sino-Japanese War can be seen as an extension of these party power struggles.

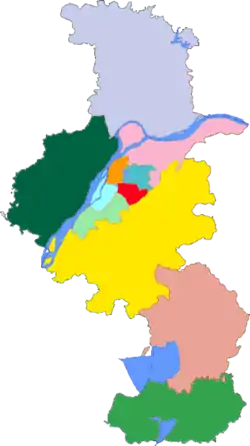

These civil wars extended Chiang's direct rule from four provinces to eleven just prior to the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. In this sense, Chiang could not be described as ruler of China as he was more of a hegemon.

Suppression of Communists and other parties

The Chinese Civil War which began with the purge of communists in 1927 would continue until the forming of the Second United Front in December 1936. During this period, the Nationalists tried destroying the Communists by using Encirclement Campaigns. The failure of early Communist strategy of urban warfare led to the rise of Mao Zedong who advocated guerrilla warfare. The Communists were much weaker in the urban areas due to secret police repression led by Dai Li. Many Communists and suspected or actual Communist sympathizers were imprisoned, including the wife and four year old daughter of Marshal Nie.[2]

Other parties that were heavily persecuted were the Young China Party and the "Third Party". They would remain banned until the Second Sino-Japanese War when they were allowed into the Second United Front as part of the China Democratic League.

Warlord conflicts during the Nanjing decade

Conflicts with Japan and Soviet Union

- Sino-Soviet conflict (1929)

- Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang

- Xinjiang War (1937)

- Nanking incident of 1927

- Jinan incident

Reforms

China's first government sponsored social engineering program began in 1934 with the New Life Movement.[3] In addition, non-governmental reforms, such as the Rural Reconstruction Movement made substantial progress in addressing the problems of the countryside.

Conclusion

The decade came to an end with the Second Sino-Japanese War. Being located near the coast, it was vulnerable so the capital was moved to Chongqing for the duration of the war. While the transfer of the capital marked its political end, the symbolic end was the Nanjing Massacre (the Rape of Nanjing) when up to 300,000 inhabitants died during the Japanese occupation.

References

- Maddison, A. (1998). Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run. Paris: OECD Development Centre.

- "中科院院士丁衡高与妻子聂力中将简介" [Introduction to the Chinese Academy of Sciences scholar Ding Henggao and his wife Middle General Nie Li]. Meili de Shenhua (in Chinese). 10 April 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Alan Lawrance (2004). China Since 1919: Revolution and Reform : a Sourcebook. Psychology Press. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-415-25142-6.

- Peter Zarrow. China in War and Revolution, 1895–1949. Includes Chapter 13: "The Nanjing decade, 1928–1937: The Guomindang era" (pp. 248–270). Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-36448-5.