National Day of Spain

The National Day of Spain (Spanish: Fiesta Nacional de España) is the official name of the national festivity of Spain. It is held annually on 12 October and is a national holiday. It is also traditionally referred to as the Día de la Hispanidad (Hispanicity), commemorating the Spanish legacy to the world, especially in America.[1]

| National Day of Spain | |

|---|---|

"First tribute to Columbus (October 12, 1492)", José Garnelo y Alda,1892, Naval Museum of Madrid | |

| Official name | Fiesta Nacional de España |

| Observed by | Spain |

| Date | 12 October |

| Frequency | Annual |

.svg.png.webp)

The celebration of the National Day of Spain is the day the Spanish people commemorates the history of the country, recognising and giving value of what has been achieved together and to reconfirm the commitment for the future as a nation. The 12 of October celebrates union and brotherhood, also showing the ties of Spain with the international community.[2][3][4][1]

The Spanish law declares

« the date chosen, October 12, symbolizes the historical anniversary in which Spain, about to conclude a process of State construction based on our cultural and political plurality, and the integration of the kingdoms of Spain into the same monarchy, begins a period of linguistic and cultural projection beyond European limits »[5]

La Fiesta Nacional de España conmemorates the discovery of the Americas by Cristopher Columbus for Spain on October 12, 1492, as a key point for the Spain's overseas projection and legacy to the world and in the Americas in particular and the vast, common heritage with the today's American countries, which integrated the Spanish Empire, the first global power in the world history.[6]

October 12 is also the Official Spanish Language Day, the Feasts of both Our Lady of the Pillar and the Virgin of Guadalupe as well as the Day of the Spanish Armed Forces.[7]

The 12 of October is also an official festivity in most Hispanic America, though under varying names ( Día de la Hispanidad, Día de la Raza, Día del Respeto a la Diversidad Cultural, Día de la Resistencia Indígena, etc.) mainly celebrating the historical and cultural ties among them and between them and Spain and their common Hispanic and pre-Hispanic native-American heritage ; and further celebrated in the United States, as the Columbus Day.[8][9]

Observance

The National Day of Spain is a national holiday in the whole country, so all central and autonomous communities institutions and administration offices are closed on that day as well as banks and commerces. The National Day is massively celebrated in Spain through numerous public and private events organized throughout the country to praise the nation's heritage, history, society and people. The festivity is also celebrated by Spanish communities worldwide. Solemn acts of Tribute to the National Flag take place in different locations of Spain and abroad. The most important by far is the one held in the capital, Madrid, along with the Armed Forces parade. Other tribute, cultural, religious and vindicative parades and demonstrations are also organised by civil society actors across Spain.

While the National Day is celebrated exclusively on October 12, the national holidays takes, with no exception, a long weekend, at least 3 days, for the citizens' leisure and enjoyment. Taking the advantage of these short holidays, many people travel these days in Spain, specially to visit other cities and emblematic places within the country. Common destinations are Aragon and its capital, Zaragoza, where the festivity of "Our Lady of the Pillar" (La Virgen del Pilar), "Mother of the Hispanic Peoples", also falls on this date. For this reason, these holidays are also known in Spain as the « Long weekend of the Pillar » (Puente del Pilar). This way of celebrating certainly strengthens the sense of national unity and cohesion as well as the sense of national belonging and purpose.

Indeed, though these holidays are short, many citizens take some days off travelling around Spain thanks to the well developed highway network and specially the high-speed train network, the largest in Europe and second in the world. Between five and more than six million road travels occur during these holydays in Spain for the State Traffic Office plans and implements specific road and driving safety measures, including alcohol, drugs and speed controls.[10]

Historical background

The roots of today's Spanish identity and cultural diversity are to be found in the interaction and fusion of peoples which have over the course of three millennia arrived and settled in Hispania (in Latin) or Iberia (in Greek), among them Tartessians, Vascones, Ligures, Iberians, Celts, Cantabri, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Carthaginians, Suevi, Vandals, Alans, Visigoths, Berbers, Arabs...). Hispania was already identified as an autonomous entity by historians from the Antiquity (Estrabo, Asclepiades of Mirlea). In Early Middle Ages, Spain, as an entity of its own, and Spanish identity proud can be already traced in 5th and 6th centuries' works by Bishops Paulus Orosius and Hydatius and most importantly Saint Isidore of Seville with his Laus Spaniae praising:[11][12][13][14][15]

Of all the lands from the west to the Indies, you, Spain, O sacred and always fortunate mother of princes and peoples, are the most beautiful.[16]

At the dawn of the Early Modern Period, the marriage and joint rule of Isabella I of Castile and Fernando II of Aragon in 1469 marked the de facto unification of Spain, joining what contemporaries referred to as "the Spains". After the conquest and fall of the Kingdom of Granada, the last Muslim-ruled polity in the Iberian Peninsula (see Reconquista) in January 1492, the Hispanic Monarchs, Isabel and Fernando, soon after getting the title of « Catholic King and Queen » from Pope Alexander VI, agreed to undertake the charting of a new commercial maritim route to Asia sailing westwards through the Mare Tenebrosum (medieval name for Atlantic Ocean), a project proposed to them by Cristopher Columbus, a genovese navigator and cartographer. This move was provoked by the control of the historical land and maritime spice trade routes by the Ottoman Empire pursuant to the conquest of Constantinople (today's Istanbul) and the end of the Eastern Roman Empire.[17][18]

The Discovery of the Americas by the Spaniards is for many one of the truly epochal events in world history as it changed dramatically not only the vision and comprehension of the world for ever, but resulted in a new socio-economic and political order affecting millions of people both in the Old and the New World to date.[19] The conmemoration emphasizes the discovering of America and the pioneering efforts and contributions of Spain in America and to the world through centuries, from the world exploration to the Spanish influence and shaping of Hispanic American societies.[2][3][1][20]

In this sens, la Fiesta Nacional traditionally celebrates the Hispanidad (Hispanicity) as a long lasting historic and present day expression of a multiethnic, multicultural community spread worldwide, all sharing a Spanish cultural heritage, most importantly the Spanish language, and in particular referred to the Hispanic American countries, based on the biological and cultural mestizaje of peoples achieved under 400 years of Spanish rule, between the late 15th and the late 19th centuries.[21]

The Spanish legacy is evoked by Harvard University scholar Charles F. Lummis in his work « The Spanish Pioneers » when stating that

« the Spanish pioneering of the Americas was the largest and longest and most marvellous feat of manhood in all history. » and that « (t)he honor of giving America to the world belongs to Spain, the credit not only of discovery, but of centuries of such pioneering as no other nation ever paralleled in any land. »[20][22]

Origins and evolution

The far origin of the festivity is to be found in the Catholic tradition of Virgin Mary apparition "in mortal flesh" in Caesaraugusta (Roman Empire name of Zaragoza) to Apostle Saint James the Greater in AD 40 where a temple was built by the river Ebro, the first in the world dedicated to the cult of the Blessed Mother. Pilgrimage to Zaragoza to venerate Our Lady of the Pillar started in early XIII century. Together with Saint James in Compostela, Our Lady of the Pillar has centered the spirituality of the Christians in the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. [23]

On May 27, 1642, the city of Zaragoza designated the Virgen del Pilar as symbol of the Hispanidad (Hispanicity) and the date became a feast in commemoration of the "coming of Our Lady" to the city.[24]

In 1730, the Pope Clement XII allowed the feast of Our Lady of the Pillar to be celebrated all over the Spanish Empire thereon.[2]

On September 23, 1892, the queen regent of Spain, Maria Cristina of Austria, promulgated a Royal Decree in San Sebastian, as proposed by the Prime Minister, Antonio Canovas del Castillo, declaring the 12 of October 1892 a national day in commemoration of the 4th centenary of the Discovery of America.[2][25]

The preamble of said decree states that the government had “considered appropriate to explore the position of all the American countries and Italy, as homeland of Columbus, to see if, by joint agreement, that commemoration could be vested with greater importance.”

The preamble continues pointing out that “most Governments of America have already adhered to the idea in principle, like that of the United States as well as those of the Hispanic American Republics, with few exceptions, maybe because of temporary circumstances, which shall probably not prevent an unanimous resolution, and, from its part, the Government of his S.M. the King of Italy has also welcomed the invitation ( ) in the most cordial and satisfactory way.” It is therein further stressed out the opportunity of “perpetuating” such a commemoration as a National Day of Spain.[26]

The Hispanidad was celebrated again in Spain from 1935, when the first festival was held in Madrid.[27] The day was known as Día de la Hispanidad ("Day of Hispanicity"), emphasizing Spain's connection to the international Hispanic community.[28][2][25]

The Hispanidad linked to the Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar as historical background and symbology of the National day of Spain are well expressed in a 1939 letter addressed by an Argentinian donor, Doña Soledad Alonso de Drysdale, to the Spanish government regarding the fundraising to complete the building of the last two of four towers of the Cathedral of the Pillar:[24]

« If, effectively, the funding comes from the Hispanic America, these two towers will become an enviable symbol of hispanicity, raised in the city capital of the kingdom who advanced the money used for the discovery of the New Word. (...) On a January 2, feast of the Coming of the Virgin Mary in mortal flesh to Zaragoza, Granada surrendered to the Catholic Kings so could Isabel and Ferdinand dedicate time and plan the enterprise proposed to them by the great navigator ; on an October 12, feast of Our Lady of the Pillar, the three inmortal caravels arrived to the first American lands. (...) If the architecture of the cathedral is completed and culminated with money from overseas, the symbolic value of the Saint Metropolitan Temple as Sanctuary of the Hispanidad will be totally affirmed. »

from the original

«Si, en efecto, de la América Hispana viene el dinero, esas dos torres serán un símbolo envidiable de hispanidad, levantado en la capital del reino que anticipó el dinero para el descubrimiento del Nuevo Mundo. (...) En un día dos de enero, fiesta de la Venida de la Virgen en carne mortal a Zaragoza, se rendía Granada a los Reyes Católicos y podían dedicar Isabel y Fernando tiempo y meditaciones a la empresa que les proponía el gran navegante; en un día 12 de octubre, fiesta de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, las tres inmortales carabelas llegaban a las primeras tierras americanas. (...) Si es con dinero de Ultramar como (...) se completa y corona la arquitectura de la catedral, el valor simbólico del Santo Templo Metropolitano como Santuario de la Hispanidad habrá quedado consagrado totalmente.[29]

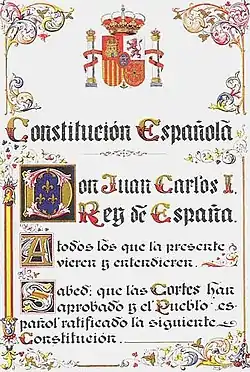

In 1981, soon after the approval of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, the national day is renamed "Fiesta Nacional de España y Día de la Hispanidad" by Royal Decree[28][30] On 7 October 1987 the mention to Hispanidad is discarded and the name is changed again to Fiesta Nacional.[5] The 12 October became one of two national celebrations, along with Constitution Day on 6 December.[28][7]

Spain's "national day" had moved around several times during the various regime changes of the 20th century; establishing it on the day of the Discovery of America international celebration was part of a compromise between conservatives, who wanted to emphasize the status of the monarchy and Spain's history, and the left-wingged parties, who wanted to commemorate Spain's burgeoning democracy with an official holiday.[7] While the manifest ties of Spain with Hispanic America are not questioned, the removal of the Hispanidad from the name of the national festivity aims to avoid any controversy with different sensibilities regarding the so-called conquest, projection and rule of the Americas by Spain during the imperial period.[31]

The participation of the Armed forces in the celebration of the National Day was stablished in 1997 by Royal Decree, which regulates the conmemoration and tribute acts to be performed by the Armed forces on the National Day of Spain. It actually transfers the most relevant acts of the Armed forces Day, traditionally celebrated separately in springtime, to October 12. This measure aimed, on the one hand, to integrate in the same festivity all the historic and cultural elements of the Spanich Nation, and on the other hand, to enhance the identification of the Armed forces with the Spanish society which they serve. Other civic-military events are also organised around Oct 12, including military training and exhibitions, cultural and sport events, aiming to facilitate the citizens to get a better knowledge of the Armed forces.[32]

Celebrations

.jpg.webp)

Public and civil society celebrations of the National Day are numerous and of different natures. Solemn Acts of Tribute to the National Flag, symbol of unity and of national coexistence, take place in different locations of Spain. The most important is the one traditionally held in the capital, Madrid, along with the Armed forces and State Security Forces parade. Other tribute and vindicative parades and demonstrations are also organised by civil society actors across Spain.

While the reference to 'Hispanidad' was removed from the official name of the festivity, the tradition of celebrating somehow this phenomenon is massively observed in Spain as it is celebrated by Hispanic peoples worldwide. Celebrations emphasizing the discovering of America and the pioneering efforts and contributions of Spain in America and to the world through centuries, from the world exploration to the Spanish influence and shaping of Hispanic American societies, are traditionally held.[33][2][25][20][15]

Officially commemorated until 1987, the Hispanic Day (Dia de la Hispanidad) has continued to be spontaneously celebrated by Spanish people with both a cultural and a religious dimension. It celebrates the Hispanic diversity, brotherhood, common heritage and cultural ties between Hispanic countries. This section should help to seize what Spain celebrates on its National Day and how.

Tribute to the Flag and Armed forces Parade

The celebration traditionally includes a parade of the Spanish Armed forces (military) and the State Security Forces (law enforcement), usually held in Madrid, attended by high institutional and political representatives including the King of Spain, head of state and commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, together with the Royal Family, the Presidents of the Government, the Parliament and the Judicial Power and other central and autonomous communities administrations' representatives. Political and institutional delegations from other guest countries, including military forces participating in the parade, also attend the event. The parade expresses the commitment of the Armed and the State Security forces with the society and its contribution to the international community.[34]

But the most important role is usually reserved to the Spanish flag, symbol of unity and of national coexistence. For several consecutive years the Spanish Air Force aerobatics paratroop unity has performed a jump carrying a massive Spanish flag to land by the Royal tribune presiding the parade. Then the tribute to the national flag, with its raising while the national anthem is performed. Then, tribute is paid to the soldiers who gave their lives for Spain which is followed by an aerial and land civil-military parade, which usually includes a display by the Spanish Air Force's aerobatics team, the Patrulla Águila.

The Armed Forces Parade is one of the most multitudinous event in Spain with thousands of citizens celebrating the feast and gathering along the route parade where they can show their affection to the Royal family and to the Armed Forces and to the State Security forces as they march through.

As for many other public events, the 2020 Armed Forces Parade was cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic in the country and substituted by an civi-military institutional act in the Royal Palace's court where the Tribute to the Spanish flag could be paid.

Spanish culture

Expression of the rich cultural diversity of Spain, the National Day is massively celebrated through numerous public and private events to praise the nation's heritage, history, society and people.[35] October 12 feast actually celebrates the unique "Spanish lifestyle"[36] and shows the essence of the many local, regional and national festivities and traditions celebrated in Spain throughout the year, some enjoying international fame. Dozens of thousands of people invade the streets to show their national proud, whether in colorful parades and demonstrations or just spontaneously on their own. People dressed in traditional regional or historic costumes as well as folk, classical and modern music concerts and street shows are unavoidable features of the celebrations. Hispanic communities in Spain also participate in parades displaying their national colors and their countries' typical garments marching along to the sound of their respective upbeat folk tunes. La Hispanidad is in the air.

No food, no feast: The Spaniards usually gather around a good meal in family and friends reunions whether at home or in bars and restaurants and they do not miss the tradition at the National Day. Open air or indoor meals organized by institutions or civil society actors are very popular as well. On the menu: the marvelous Spanish food with its distinctive regional singularities. A part from the worldwide famous tapas, paellas, jamon serrano and tortilla de patatas, an amazing festival of rich dishes, salads, soups, stews and roasts, fish and seafood, etc. can be enjoyed anywhere in Spain as they are a manifestation not only of the Spanish gastronomy but also of the great agricultural, cattle-raising and fishering millenary tradition of Spain.[37]

Then, over two thousand years old viniculture ensure to harmoniously pair those meals with a good wine produced, virtually, in any corner of the Spanish country land. Spanish people do know how to celebrate around the table and they do it specially on October 12.

Spanish Art and Architecture also play an importante role in the celebration of the National Day. October 12 is an Open Doors Day in many museums and historical sites. From Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages, through Roman, Visigothic, Al-Andalus, Romanesque, Gothic, Mudejar, Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical, to XXth century Modernism and Contemporary, Spanish Architecture legacy is simply awesom reflecting the great historical and geographical diversity of the country.

Ranking third worldwide in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites' list, with 48 sites therein inscribed, is only a tiny hint of the countless artistic and architechtonical treasures spread all over the Spanish territory, truly. Many citizens take the opportunity each October 12 to visit them as well as to admire the artworks of the classical and contemporary Maestros (Picasso, Dali, Goya, Velazquez, Miro, etc.) and other artists held in the Spanish museums, some being world-class art institutions, like the Madrid triad El Prado, Reina Sofia or Thyssen-Bornemisza Museums, the so-called “Golden Triangle of Art”, simply the best pictoric collection of the world.[38]

The Hispanic dimension of the festivity gives place too to recall the Spanish Art and Arquitecture legacy overseas, mainly in the Americas at the Imperial age, including the present day United States soil. Spanish manufacture and design of Renaissance and Baroque styles erected historic quarters and buildings of most beautiful American towns and cities, today symbols of identity and object of proud of the Hispanic people.[39] As an expression of this Hispanic cultural heritage, several dozens of sites all along the Americas are also listed in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[40][41]

Much of the above has been achieved with a common instrument, the Spanish Language, the world's second-most spoken native language today (soon 500 million people) and the world's third-most spoken language.[42] Institutions such as the Instituto Cervantes organize events, workshops and other cultural activities in different locations worldwide to celebrate the Hispanic legacy through the Spanish language phenomena and its fructiferous literature through centuries. For some years since 2010, the Spanish Language Day was also celebrated on Oct 12 by the United Nations, later moved to April 23 to commemorate Miguel de Cervantes' death anniversary on that day.

Religious dimension

The Spanish legacy has a strong religious component expressed with the traditional celebration of the Day of Our Lady of the Pillar, "Mother of the Hispanic Peoples" and very popular in Spain; and of the Our Lady of Guadalupe, “Queen of the Hispanidad” who enjoys a high popularity in Hispanic America, both festivities being held as well on October 12.

Our Lady of the Pillar (la Virgen del Pilar) is patroness saint of both the autonomous community of Aragon and its capital, the city of Zaragoza as well as of the Guardia Civil (Spanish Civil Guard) and the Spanish Navy submarine force among others. It commemorates the coming of the Virgin Mary to Zaragoza in AD 40, according to tradition, her only apparition while she was still alive and the first to the Hispanic people. Since the religious feast day coincides with the discovery of the Americas (12 October 1492), Pope John Paul II praised El Pilar as "Mother of the Hispanic Peoples" during both his visits to the Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar.[43][44]

The 12 of October, also popularly known in Spain as the « Día del Pilar », attracks many people from other Spanish regions to Zaragoza, where the traditional « Ofrenda de flores a la Virgen » (Offering of flowers to the Virgin Mary), a multitudinous parade with massive social participation, including Hispanic American communities, takes place all the day long. Every nation of Hispanic colonial origin has donated national vestments for the fifteenth-century statue of the Virgin, which is housed in the chapel of the cathedral.[45]

Another relevant symbol of Hispanic heritage both in Spain and in Hispanic America is the cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which feast is celebrated in Extremadura on the Dia de la Hispanidad, each October 12, since she holds the title of Queen of Hispanicity since 1928. The origin of this religious tradition is the Christian legend of the apparition of the Blessed Mother to a shepherd in the XIV century indicating the place to find a wooden statue of the Virgin Mary carved by Luke the Evangelist buried centuries ago by local clergymen to prevent any damage of it from the Moorish invaders. The Monastery built thereafter on the site where the statue was found soon became the most important place of pilgrimage in Castile and fair rich.[46][47]

The Catholic Kings met in the Monastery with Columbus in June 1492, which resulted in the Monarchs' authorization of the exploration endeavor and the dispatch of the first Royal injunctions to organize the “voyage into the unknown”. In 1493, Columbus went back to the Monastery to thank Our Lady of Guadalupe for his successful first voyage and in his second, he baptized a newly found Caribbean island as Guadalupe, in honor to the Spanish Virgin. This, together with the fact that many Spanish explorers came from Extremadura and the utmost popularity of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Castile, are the reason behind the spread of the worship throughout America and her canonical coronation as Queen of Hispanicity.[46][47]

Armed Forces Parade in Madrid.

Armed Forces Parade in Madrid. Fiesta Nacional de España 2014 - Madrid, Spain.

Fiesta Nacional de España 2014 - Madrid, Spain. Dignitaries attending the military parade, 1988.

Dignitaries attending the military parade, 1988. Stand of dignitaries in the military parade, 2008.

Stand of dignitaries in the military parade, 2008. Air Force parade, 2013.

Air Force parade, 2013. Army tank on parade in Madrid, 2009.

Army tank on parade in Madrid, 2009. Eternal flame.

Eternal flame. Offering of Flowers and Basilica del Pilar, Zaragoza.

Offering of Flowers and Basilica del Pilar, Zaragoza.

See also

- Public holidays in Spain

- Hispanidad

- Mestizo

- Spanish language

- Culture of Spain

- UN Spanish Language Day

- Institute of Cultural Heritage of Spain

- Spain

- History of Spain

- Discovery of America

- Hispanic America

- Spanish Armed Forces

- National Hispanic Heritage Month

- Timeline of support for Indigenous Peoples' Day

- Indigenous Resistance Day

- Columbus Day

- Native American Day

References

- Paloma Aguilar, Carsten Humlebæk, "Collective Memory and National Identity in the Spanish Democracy: The Legacies of Francoism and the Civil War", History & Memory, April 1, 2002, pag. 121-164

- David MARCILHACY « América como factor de regeneración y cohesión para una España plural: “la Raza” y el 12 de octubre, cimientos de una identidad compuesta », Hispania (Madrid), vol. LXXIII, no. 244 (mayo-ag. 2013), p. 501-524

- David Marcilhacy "LA PÉNINSULE IBÉRIQUE ET LE MARE NOSTRUM ATLANTIQUE: IBÉRISME, HISPANISME ET AMÉRICANISME SOUS LE RÈGNE D’ALPHONSE XIII DE BOURBON" Revista de História das Ideias, Vol. 31 (2010), pags. 121-154

- https://www.defensa.gob.es/12octubre/

- https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/1987/BOE-A-1987-22831-consolidado.pdf, free translation

- Thomas, Hugh (August 11, 2015). World Without End: Spain, Philip II, and the First Global Empire. Random House. pp. 496 pages. ISBN 0812998111

- Molina A. de Cienfuegos, Ignacio; Martínez Bárcena, Jorge; Fuller, Linda K. (Ed.) (2004). "Spain: National Days throughout the History and the Geography of Spain". National Days/National Ways: Historical, Political, and Religious Celebrations around the World: 253. ISBN 978-0-275-97270-7. Retrieved 30 September 2009.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- https://www.hispanicheritagemonth.gov

- https://www.history.com/topics/hispanic-history/hispanic-latinx-milestones

- http://www.dgt.es/es/prensa/notas-de-prensa/2017/20171011-preparado-operativo-especial-trafico-el-pilar-2017.shtml

- Andrew H. Merrills, History and Geography in Late Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 185–96.

- Torrecilla, Jesús (2009) "Spanish Identity: Nation, Myth, and History," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 2, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1699

- Guido Donini and Gordon B. Ford, Jr., translators. Isidore of Seville's History of the Kings of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1966).

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Spain/History

- Gustavo Bueno, "España no es un mito. Claves para una defensa razonada" Temas de Hoy, Madrid 2005, ISBN 84-8460-495-0

- Kenneth Baxter Wolf, CONQUERORS AND CHRONICLERS OF EARLY MEDIEVAL SPAIN, TRANSLATED TEXTS FOR HISTORIANS, 9 (LIVERPOOL, 1990), PP. 81–3

- Kamen, Henry (2003). Empire: How Spain Became a World Power, 1492-1763. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-093264-3

- Bethany Aram, "Monarchs of Spain" in Iberia and the Americas. Santa Barbara: ABC Clio 2006.

- Tarver, H. Michael; Slape, Emily (2016). The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 159. ISBN 9781610694216

- Charles F. Lummis. The Spanish Pioneers (PDF).

- 1962-, González Fernández, Enrique (2012). Pensar España con Julián Marías. Ediciones Rialp. ISBN 978-8432141669.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Charles F. Lummis. The Spanish Pioneers.

- https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/nuestra-senora-del-pilar-our-lady-of-the-pillar-622

- Cenarro, Ángela (1997). "La Reina de la Hispanidad: Fascismo y Nacionalcatolicismo en Zaragoza. 1939–1945" (PDF). Revista de historia Jerónimo Zurita. Institución Fernando el Católico. 72: 91–102. ISSN 0044-5517.

- David MARCILHACY « Las fiestas del 12 de octubre y las conmemoraciones americanistas bajo la Restauración borbónica: España ante su pasado colonial », Revista de Historia Jerónimo Zurita (Zaragoza), n°86 (2011), p. 131-147

- https://www.boe.es/datos/pdfs/BOE/1892/269/A01077-01077.pdf, a free translation

- ""Día de la Hispanidad"/"Fiesta de la Hispanidad"". filosofia.org (in Spanish). 2004. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Prakke, L.; C. A. J. M. Kortmann; J. C. E. van den Brandhof (2004). Constitutional Law of 15 EU Member States. Kluwer. p. 748. ISBN 90-13-01255-8. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- Heraldo de Aragón, 25-5-1939 y 26-5-1939, a free translation

- https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/1982/BOE-A-1982-1-consolidado.pdf

- Encarnación, Omar Guillermo (2008). Spanish Politics: Democracy after Dictatorship. Polity. p. 43. ISBN 0-7456-3992-5. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Royal Decree 862/1997, of June 6, https://boe.vlex.es/vid/actos-conmemorativos-fiesta-defensa-15370717

- https://www.lasprovincias.es/sociedad/12-octubre-fiesta-nacional-20201010082642-nt.html

- "The 12th of October Parade". Turismo Madrid.

- https://www.spain.info/en/art-culture/

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Spain/Daily-life-and-social-customs

- http://chatteringkitchen.com/2011/10/11/fiesta-nacional-de-espana-celebrate-spains-national-day-with-authentic-spanish-cooking/

- https://theculturetrip.com/europe/spain/articles/madrids-golden-triangle-el-prado-reina-sofia-and-thyssen-bornemisza/

- http://npshistory.com/publications/hispanic-reflections.pdf

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/lac/

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/?search=&searchSites=&search_by_country=®ion=3&search_yearinscribed=&themes=&criteria_restrication=&media=&order=country&description=&type=cultural

- https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/espanol_lengua_viva/pdf/espanol_lengua_viva_2020.pdf El español, una lengua viva. Informe 2020.

- (2011-10-12). "At the centre of Marian faith: Spain’s National Holiday and the Feast of the Virgin of Pilar". Custodia Terræ Sanctæ. Retrieved on 25 February 2013.

- https://catholicism.org/our-lady-of-the-pillar.html

- https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/cw/post.php?id=673

- "Our Lady of Guadalupe in Spain". Our Lady in the Old World and New. Medieval Southwest, Texas Tech University.

- Richard C. Trexler, Religion in Social Context in Europe and America 1200-1700 (Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2002)