National Museum of the Philippines

The National Museum of the Philippines (Filipino: Pambansang Museo ng Pilipinas) is an umbrella government organization that oversees a number of national museums in the Philippines including ethnographic, anthropological, archaeological and visual arts collections. Since 1998, the National Museum has been the regulatory and enforcement agency of the Government of the Philippines in the restoring and safeguarding of important cultural properties, sites, and reservations throughout the Philippines.

| |

.svg.png.webp) Location within Rizal Park | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 29, 1901[1] |

| Jurisdiction | Philippine arts and cultural development |

| Headquarters | National Museum of Fine Arts, Padre Burgos Avenue, Rizal Park, Ermita, Manila, Philippines 14°35′12″N 120°58′52″E |

| Annual budget | ₱493.08 million (2020)[2] |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent department | Department of Education National Commission for Culture and the Arts |

| Website | www |

The National Museum operates the National Museum of Fine Arts, National Museum of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, and National Planetarium, all located in the National Museum Complex in Manila. The institution also operates branch museums throughout the country.

History

The first predecessor to today's National Museum was the Insular Museum of Ethnology, Natural History, and Commerce under the Department of Public Instruction, created in 1901 by the Philippine Commission. In 1903, the Museum was subsequently transferred to the Department of Interior and renamed the Bureau of Ethnological Survey. This new bureau was responsible for the Philippine participation in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904. After the exposition, it was abolished as a separate bureau and renamed the Philippine Museum.

The museum's structure again changed in 1933 when the Philippine Legislature divided the museum. The museum's Division of Fine Arts and History went to the National Library. Its Division of Ethnology went to the Bureau of Science. Finally its Division of Anthropology, which included archaeology, ethnography and physical anthropology, and the other sections of natural history of the Bureau of Science, were organized into a National History Museum Division. This was transferred to the Office of the Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce in 1939.

The Japanese occupation of the Philippines during World War II brought the divisions back under a single National Museum of the Philippines, but the museum lost a large part of its collection during the Liberation of Manila when the Old Legislative Building was destroyed by American artillery. The Legislative Building was immediately restored through the American funds bringing the museum back to its operations.

.jpg.webp)

The museum's role in cultural growth was recognized as contributing to government's desire for national development.[3] In 1966, President Ferdinand Marcos signed Republic Act No. 4846 or the Cultural Properties and Protection Act. The law designated the museum as the lead agency in the protection and preservation of the nation's cultural properties through the conduct of census, study, and declaration of such properties and the monitoring and regulation of archaeological exploration, excavation, or diggings in historical or archaeological sites. With its new powers, it was able to strengthen its cultural mandate by declaring properties, structures, and sites of historical and cultural value to the nation. The educational mandate was strengthened because it was able to inform the public of the researches it conducted and through the acquisition and exhibition of archaeological finds.

In 2019, the powers of the National Museum was further expanded through Republic Act No. 11333 which was signed into law by President Rodrigo Duterte. Under the law the museum body's official name was lengthened to National Museum of the Philippines from just being National Museum. It was also classified as a government trust attached to the government for only budgetary reasons preserving a degree of independence and autonomy. It is also mandated to establish regional museums in each of the country's administrative regions.[4]

Museums

National Museum of Fine Arts

The National Museum of Fine Arts, formerly called the National Art Gallery, is housed in the old Legislative Building. The building was originally intended as a public library as proposed in Daniel Burnham's 1905 Plan for Manila. Designed by Ralph Harrington Doane, the American consulting architect of the Bureau of Public Works, and his assistant Antonio Toledo. Construction of the building began in 1918 and completed in 1921.

The façade of the building had classical features using stylized Corinthian columns, ornamentation and Renaissance inspired sculptural forms.[5] Upon the establishment of the Commonwealth government, it was decided that the building would also house the Legislature and revisions were made by Juan Arellano, supervising architect of the Bureau of Public Works.

On July 16, 1926, the building was formally inaugurated. During the World War II, the building was heavily damaged, though built to be earthquake resistant.[5] After the war, it was rebuilt albeit less ornate and less detailed. During the Martial Law era, the Legislative Building was closed down. Today, the building holds the country's National Art Gallery, natural sciences and other support divisions.

National Museum of Anthropology

_(2014)_a0001.JPG.webp)

The National Museum of Anthropology, formerly known as the Museum of the Filipino People, is a component museum of the National Museum of the Philippines that houses the Archaeology Division, Ethnology Division, Exhibition, Editorial and Media Production Services Division (EEMPSD), Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Division (MUCHD), and Museum Services Division (MSD). It is located in the Agrifina Circle, Rizal Park, Manila across the main National Museum building which is the National Museum for Fine Arts. The building was the former headquarters of the Department of Finance.

National Museum of Natural History

It was recently announced that the third building of this museum complex — the one presently occupied by the Department of Tourism, shall be developed into the National Museum of Natural History, once the Department moves out and transfers to its permanent location in Makati. The National Museum of Natural History will have a hexagonal DNA tower structure in its center which will be the base for the ventilating roof-dome of the whole building. Living trees will also be planted within the interior of the building. It was expected to be finished in the last quarter of 2015[6] but the opening of the museum was moved sometime in 2017. In October 2017, the National Museum of Natural History officially opened to the public with its iconic Tree of Life structure.

National Planetarium

The Planetarium was planned in 1970's by former National Museum Director Godofredo Alcasid Sr. with the assistance of Mr. Maximo P. Sacro, Jr. of the Philippine Weather bureau and one of the founders of the Philippine Astronomical Society.

The building started on construction on 1974 and completed 9 months after. It was formally inaugurated on October 8, 1975. The Presidential Decree No. 804-A, issued on September 30, 1975, affirmed the Planetarium's status. The Planetarium is located between the Japanese Garden and the Chinese Garden at the Rizal Park.[7]

Regional Museums

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The National Museum has also established numerous regional museums outside Metro Manila. These regional museums are found in Angono (Rizal province), Padre Burgos in Vigan (Ilocos Sur), Kabayan (Benguet), Kiangan (Ifugao), Magsingal (Ilocos Sur), Puerto Princesa (Palawan), Butuan in Caraga region, Tabaco (Albay), Fort Pilar in Zamboanga City, Boac (Marinduque), and Jolo (Sulu). In 2018, regional branches in Basco in Batanes and Iloilo city in Iloilo province were established. A regional branch in Cebu is being developed, while a branch in Bolinao (Pangasinan) was permanently closed. Branches in Banton town in Romblon, Romblon town in Romblon, Monreal town in Ticao Island, Maitum in west Sarangani, Jolo in Sulu, Marawi city in Lanao del Sur, Guian in Eastern Samar, Davao city in the Davao region, Mati in Davao Oriental, Cabanatuan city in Nueva Ecija, Tabuk in Kalinga, Aparri in Cagayan province, Malaybalay in Bukidnon, Cotabato city in Maguindanao, Hungduan in Ifugao, Rizal town in Palawan, Bulalacao in Mindoro, and Siquijor town in Siquijor are also being eyed by the National Museum. The re-establishment of a regional museum in Bolinao is also being eyed.[8][9]

Other notable buildings

The National Museum hosts its Western Visayas (Region-6) Regional Museum in the former Iloilo Rehabilitation Center, a jail facility that was abandoned in 2006 when the inmates were transferred to the new BJMP location. Built in 1911, the old Iloilo Provincial Jail is an Important Cultural Property - a recognition of its exceptional cultural, artistic, and historical significance to the Philippines. NMP also runs a satellite office for Western Visayas at the Old Jaro Municipal Hall, a designated heritage site, in Iloilo City which was designed by architect Juan Arellano.

National Cultural Treasures

The National Museum Complex in Manila currently houses the following National Cultural Treasures:

- (1) Manunggul Burial Jar which is a unique Neolithic secondary-burial jar with incised running scrolls / curvilinear designs and impressed decorations; and painted with hematite. On top of the cover is a boat with two human figures that represent souls on a journey to the afterlife.

- (2) Calatagan Ritual Pot which was recovered in Mang Tomas Archaeological Site, Calatagan, Batangas in 1961. It is unique and classified as atypical earthenware with ancient syllabic inscription on the shoulder. The Calatagan ritual pot is the only one of its kind with an ancient script.

- (3) Maitum Anthropomorphic Burial Jar No. 13 which is unique and the only intact anthropomorphic burial jar with two arms, nipples, navel and male sex organ on the body that is found in an archaeological context. The head is unpainted and with perforations on the lid that show side parting of the hair. Its lips are colored with red hematite and accented with an incised design. It also has two ear lugs on the lower half of the urn.

- (4) Maitum Quadrangular Burial Jar which is a quadrangular jar with four ear lugs on the body and intricate scroll design emanating from a single trunk. The cover of the burial jar has a crown-like embellishment on top like birds’ head coming together. This jar has curvilinear scroll designs such as free hand painting of Tree of Life and cloud motifs. This is the earliest record of cloud design on a pottery.

- (5) Leta-Leta Jarlet with Yawning Mouth which is one of the several intact pieces of pottery recovered in Leta-Leta Cave, Northern Palawan in 1965. The cup is unique and is the only known earthenware drinking vessel in the Philippines.

- (6) Leta-Leta Footed Jarlet which was systematically retrieved in Leta-Leta Cave, Langen Island, Northern Palawan in 1965. This piece is unique and the only one of its kind so far found in the Philippines.

- (7) Leta-Leta Presentation Dish which was systematically retrieved in Leta-Leta Cave, Northern Palawan in 1965. This is the earliest type of presentation dish with lattice work of pedestal and lace design.

- (8) Pandanan 14th Century Blue-and-White Porcelain which is one of its kind. Its design, the wonderfully preserved pattern, shows the mythical qilin and phoenix cavorting between lotus scrolls. Qilin is a horse or unicorn-like creature of Chinese mythology which was considered a noble portent of good government.

- (9) Lena Shoal Blue-and-White Dish with Flying Elephant which is One of the two pieces so far recovered in the world, the Elephant Dish is made of porcelain with black and brown specks visible in the paste. On the central medallion is the flying elephant design painted in dark blue against a background of stormy and foaming waves. This is a rare representation of an elephant in early historic art.

- (10) Puerto Galera Blue-and-White Jar which was Recovered in Puerto Galera, Mindoro, this Blue-and White jar has ears, cloud collars at the shoulder, human figures and floral designs around the body, and a lotus lappet on the upper foot rim. This is a unique specimen associated with Swatow Wares.

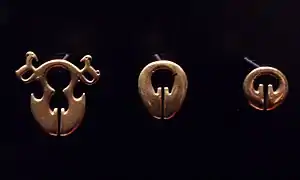

- (11) Palawan Zoomorphic Ear Pendant which is atype of Lingling-O with a double-headed pendant found in Duyong Cave. This is the most distinctive jade ornament with zoomorphic design; and a superb and beautifully proportioned example of an ancient carving in jade.

- (12) Cabalwan Earliest Flake Tools which was Collected in Awidon Mesa Formation, Espinosa Locality 4, Cagayan Province, these flake tools were recovered in the same lithology where fossils of prehistoric elephant and stegodont were retrieved.

- (13) Batangas Likha Figurines which was Collected in Calatagan, Batangas, these are the only authenticated likha.

- (14) Mataas Shell Scoop which is a concave utensil with a sharp point at one end and a figure at the other end. The latter has a right extremity that forms to what appears like an arm with five digits. The left extremity and the head are missing. The outer surface of the body whorl near the figure has an angular shoulder. This shell scoop, recovered in Cagraray Island, Albay is not bilaterally symmetrical. Shell scoops made from the body whorl of Turbo marmoratus first appeared in the Late Neolithic Period at Manunggul Cave, Quezon, Palawan.

- (15) Duyong Shell Adze which is similar to the shell adzes recovered in Micronesia and Ryuku Islands in Okinawa, Japan. The presence of shell adzes, not only in Palawan but also in Tawi-Tawi, is very significant in the study of movements of people from the insular Southeast Asia to the Pacific.

- (16) Tabon Skull Cap which was systematically retrieved during the archaeological excavation in Tabon Cave, Palawan in 1960, this bone is the earliest skull cap of modern man, Homo sapiens sapiens, found in the Philippines.

- (17) Tabon Mandible which was Systematically retrieved during the archaeological excavation undertaken in Tabon Cave, Quezon, Palawan, this is the earliest evidence of human remains showing archaic characteristics of a mandible and teeth.

- (18) Tabon Tibia Fragment which was recovered in Tabon Cave during its re-excavation in 2000 by the National Museum. The bone was identified as human and was sent to National Museum of Natural History in Paris, France for a more detailed study. Uranium-series dating technique was applied to this bone that revealed a dating of 47,000 +/- 11–10,000 years ago.

- (19) Bolinao Skull with Teeth Ornamentation which was Recovered from Balingasay Archaeological Site in Bolinao, Pangasinan were teeth with gold ornaments in 67 skulls associated with tradeware ceramics attributed to Early Ming Dynasty (15th century AD). One of the skulls is the renowned Bolinao skull where gold scales were observed on the buccal surfaces of the upper and lower incisors and canines.

- (20) Gold Seal of Captain General Antonio Morga which was Collected by underwater archaeologists at the San Diego Wreck Site off the Fortune Island, Nasugbu, Batangas, this gold seal is unique and the only one in the world.

- (21) Oton Death Mask which was collected in Oton, Ilo-ilo, this is the first gold death mask recovered systematically by archaeologists – a rare piece.

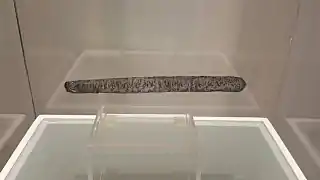

- (22) Butuan Paleograph which was found among burial coffins in Butuan, this artifact is the only one of its kind, rare and still un-deciphered. It presents 22 units of writing on a silver strip similar to a Javanese script that had been in use from the 12th to the 15th century AD. The characters display a Hindu-Buddhist influence, probably the earliest in the Philippines.

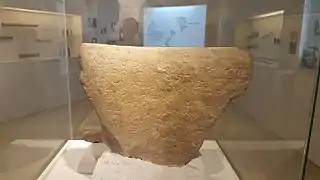

- (23) Laguna Copper Plate which has ten lines of small script characters that are impressed on one side. This rare artifact was studied by Dr. Anton Postma and Dr. Johannes de Casparis. According to them, the main language of the copper plate is old Malay but the text is sprinkled with Sanskrit, old Javanese and old Tagalog terms.

- (24) San Diego Astrolabe which was collected in San Diego Wreck Site off Fortune Island, Nasugbu, Batangas, the astrolabe consists of a bronze disc, a ring at the top by which they are suspended, and a counter weight of the bottom to stabilize them. At the center of the disc is a pivoting pointer called alidade. This piece is one of the two known existing astrolabes in the world. An instrument derived from the planispheric astrolabe invented by mathematicians in ancient Alexandria, the nautical astrolabe appeared in the Portuguese sphere of influence only in the late 15th century after it was adopted by nearly all western mariners.

- (25) Banton Burial Cloth which was found in association with coffin burial in Banton Island, Romblon Province, this burial cloth is the oldest textile associated with Yuan ceramic tradeware and the oldest textile so far found in the Philippines.

- (26) Marinduque Celadon Jar which was collected in Marinduque Province, this jar has a body embossed with Chinese dragon design which is one of the only three known of its kind in the world.

- (27) Butuan Balangay Boat which is the first balangay excavated by the National Museum, this boat is dated 320 AD, the earliest watercraft so far found in the country.

- (28) Butuan Crucible which was collected in Butuan City in 1986, this crucible with multi-colored silica drippings was used for smelting metal to produce precious personal ornaments.

- (29) Alcaiceria de San Fernando Marker of 1762 from Binondo. Deeply carved into this piedra china (Chinese granite) marker, details among other things the then-prevailing exclusion policy for non-Christian Chinese traders during the monsoon season in the Philippines under the Spanish colonial period.

- (30) Assassination of Governor Bustamante and His Son by: Félix Resurrección Hidalgo y Padilla. The oil-on-canvass painting depicts the assassination of Governor Bustamante, who wanted to clean government's corrupt ways. The governor clashed with Manila archbishop and Spanish priest Fernando dela Cuesta, a known protector of corrupt officials during the Spanish era in the Philippines. This clash in ideals led to Bustamante to detain the archbishop, which irked various clergymen who rampaged in the Palacio del Gobernador. Caught by surprise, Bustamante was killed by the clergymen and dela Cuesta was freed. When the son of Bustamante heard the news, he rushed to the palace, only to be killed by the clergymen as well. The vivid depictions of the sad event won Hidalgo a silver medal in the 1884 Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in Madrid, Spain.

- (31) Feeding the Chicken Painting by: Simon Flores. The oil-on-canvass painting of master painter Simon Flores depicts the mother and daughter caught feeding chickens in a commonplace setting. The painting is regarded as a transition from the miniaturist school of homegrown portraitists of the nineteenth century to the idyllic tableaux of the American period academic masters.

- (32) International Rice Research Institute by: Vicente Manansala. The twin murals of National Artists Vicente Manansala are a lighthearted narration of Filipino rural life. One is a joyful, pastel-colored medley of labor; scenes of fishing and rice-planting flank the two sides, while at the center, as focal point, is a woman bathing a child. The second painting is a spectacle of small-town festivities: on the left is a game of sipa, the national sport; on the right are two men competing in a carabao race. The stretch of canvas is lined with a crowd of people watching two roosters in midair cockfight.

- (33) Basi Revolt Paintings by: Esteban Pichay Villanueva. It depicts the Basi Revolt, also known as the Ambaristo Revolt, which was a revolt undertaken from September 16 to 28, 1807. It was led by Pedro Mateo and Salarogo Ambaristo (though some sources refer to a single person named Pedro Ambaristo), with its events occurring in the present-day town of Piddig in Ilocos Norte. This revolt is unique as it revolves around the Ilocanos' love for basi, or sugarcane wine. In 1786, the Spanish colonial government expropriated the manufacture and sale of basi, effectively banning private manufacture of the wine, which was done before expropriation. Ilocanos were forced to buy from government stores. However, wine-loving Ilocanos in Piddig rose in revolt on September 16, 1807, with the revolt spreading to nearby towns and with fighting lasting for weeks. Spanish led troops eventually quelled the revolt on September 28, 1807, albeit with much force and loss of life on the losing side. The series of 14 paintings on the Basi Revolt by Esteban Pichay Villanueva currently hangs at the Ilocos Sur National Museum in Vigan City.

- (34) Maradika Qur'an of Bayang (From Lanao del Sur). The book is the oldest known Qu’ran (Koran) written in the Philippines. It belonged to the Sultan of Bayang in Lanao del Sur and was copied by Saidna, one of the earliest hajji from the Philippines. The Quran of Bayang is believed to be one of the few copies translated into a non-Arabic language—that is, using a language in the Malay family and handwritten in Arabic calligraphy. The book was taken away by the government during the martial law era after the first lady took a liking on its value. It was then housed in the presidential palace. When the dictatorship was ousted, the book was afterwards housed in the National Museum.

- (35) Mother's Revenge Sculpture in terra cotta (clay) is an allegorical representation of what was happening in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial period. Shown is a dog trying to rescue her helpless pup from the bite of the crocodile. The mother dog represents “mother Philippines” and the patriots who are doing their best to save the defenseless countrymen – the pup – from the cruelty of the Spaniards as represented by the crocodile. It was made by revolutionary hero Jose Rizal during his exile in Dapitan.

- (36) Spoliarium by: Juan Luna. The oil-on-canvass painting by Filipino master painter Juan Luna was first submitted to the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in 1884 in Madrid, Spain, where it garnered a gold medal. In 1886, it was sold to the Diputación Provincial de Barcelona for 20,000 pesetas. It currently hangs in the main gallery at the ground floor of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Manila, and is considered by the Filipino art community as the most prized painting made by a Filipino master painter.

- (37) The Parisian Life by Juan Luna. Also known as Interior d'un Cafi, it is an oil-on-canvass impressionistic painting by master painter Juan Luna. The painting exemplifies the Luna's Parisian period, a time when his style moved away from having “dark colors of the academic palette” and became “increasingly lighter in color and mood” due to his stay in Paris from 1882 to 1893.

- (38) The Progress of Medicine in the Philippines by Carlos V. Francisco. It comprises four oil paintings on canvas executed by National Artist Carlos V. Francisco in 1953, which were commissioned for the main entrance hall of the Philippine General Hospital in Manila. The paintings depict the advancement of medicine in the Philippines until the middle of the 20th century.

- (39) Una Bulaqueña Painting by: Juan Luna. Also known as La Bulaqueña, literally "the woman from Bulacan", the oil-on-canvass painting is a "serene portrait", of a Filipino woman wearing a Maria Clara gown, a traditional Filipino dress that is composed of four pieces, namely the camisa, the saya (long skirt), the panuelo (neck cover), and the tapis (knee-length overskirt). The name of the dress is an eponym to Maria Clara, the mestiza heroine of Filipino hero José Rizal's novel Noli Me Tangere. The woman's clothing in the painting is the reason why the masterpiece is alternately referred to as Maria Clara.[10]

Monreal Stone

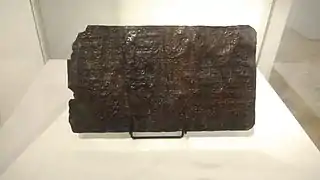

Monreal Stone

Lingling-o

Lingling-o

Guillermo Tolentino Sculptures

Guillermo Tolentino Sculptures

Seminars and lectures

The National Museum offers numerous lectures, workshops, and seminars annually. However, most of these events happen at the museums within Metro Manila. More than 80% of provinces in the country have yet to possess a museum under the authority of the National Museum. A partial reason for this lacking is the non-existence of a Department of Culture. In late 2016, a bill establishing the Department of Culture and the Arts and another bill strengthening the National Museum, including its regional museums, were filed by Senator Loren Legarda in the Senate. Both bills were formally introduced in early 2017.[11]

References

- "Commemorative Program for the 111th Foundation Day of the National Museum" (PDF). Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office (PCDSPO). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- Aika Rey (January 8, 2020). "Where will the money go?". Rappler. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Ferdinand Marcos, New Filipinism: The Turning Point, State of the Nation Message to the Congress of the Philippines, January 27, 1969 [on-line] accessed from https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1969/01/27/ferdinand-e-marcos-fourth-state-of-the-nation-address-january-27-1969/.

- "Duterte signs law giving more powers the National Museum of the PH » Manila Bulletin News". News.mb.com.ph. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- Alarcon, Norma (2008). The Imperial Tapestry, American Colonial Architecture in the Philippines. University of Santo Tomas Publishing House. p. 133. ISBN 9789715064743.

- DOT building to be transformed into Museum of Natural History. Lifestyle Inquirer

- Branches of the National Museum. National Museum of the Philippines

- "Info". www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "Happy New Year from our flagship museum... – National Museum of the Philippines". Facebook. December 31, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "LOREN LEGARDA: Sponsorship Speech: Senate Bill No. 1529, Committee Report No. 140". YouTube. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

Further reading

- Lenzi, Iola (2004). Museums of Southeast Asia. Singapore: Archipelago Press. p. 200 pages. ISBN 981-4068-96-9.