Natural History Museum of the University of Pisa

The Natural History Museum of the University of Pisa is a natural history museum in the city of Pisa in Tuscany, Italy.

Museo storia naturale università di Pisa | |

| |

Natural History Museum of the University of Pisa | |

Location of Museum in Pisa | |

| Established | 1596 |

|---|---|

| Location | via Roma 79,Calci |

| Coordinates | 43.721947°N 10.52334°E |

| Type | Natural history museum |

| Collections | Natural history |

| Visitors | 71033 |

| Director | Bonaccorsi Elena |

| Website | https://www.msn.unipi.it/it/ |

It houses one of the largest collection of cetaceans skeletons in Europe.

The museum's oldest collections are seashells collected by the Italian invertebrate scientist, Niccolò Gualtieri. There is also an assembly of five thousand zoological specimens collected by the Italian geologist and ornithologist, Paolo Savi.

Grand Duke Ferdinand I of Tuscany established the museum in 1596 by moving specimens from the Florentine palaces of the Medici. In 1981, the museum was moved to the Pisa Charterhouse.

Organization

The museum is organized into two sectors.

One sector includes the

- Aquarium

- Temporary Exhibitions

- Prehistory of Monte Pisano

The other sector includes the permanent exhibitions of

- Historical Gallery

- Garden

- Amphibians and Reptiles gallery

- Mammals gallery

- Hall of Archaeocetes

- Cetacean gallery

- Hall of the evolution of man

- Mineral gallery

- Room "The Earth between myth and science.”

- Geological eras gallery

- Dinosaur Halls

- Evolution of birds

Aquarium

The museum has the largest freshwater aquarium in Italy[1] at 60,000 liters.[2] The first sector of the exhibition is entirely dedicated to Lake Tanganyika and hosts various specimens of cichlids belonging to the Tropheus. The second section houses dipnoi, arowana , some freshwater puffers, an axolotl colony, a softshell turtle and a mata mata specimen. The third sector is the largest tank and is dedicated to Koi carp. The fourth and fifth sectors show off world fish biodiversity with Asian giant gourami, the American Oscar fish and the alligator pike.[3]

Prehistory of Monte Pisano

This room is dedicated to the excavations that were started in 1847 of the Lion's Cave in Agnano.

Historical gallery

Blaschka glass collection

Leopold Blaschka produced marine invertebrate glass reproductions. The museum has 51 examples. The collection is a remarkable example of the fusion between science and craftsmanship.

Garden

A project to devote the garden to the plants of Monte Pisano is currently underway.

Mammal gallery

Over 300 specimens are spread over the third floor, including an example of the Père David’s deer.

Hall of Archaeocetes

There is a 50 thousand-year-old fossil skeleton of Hippopotamus antiquus. Also, there is a reconstruction of Indohyus, a terrestrial mammal ancestor of modern cetaceans. The exhibition then continues with the cast of a skeleton and the reconstruction of an Ambulocetus natans, an ancient cetacean that was probably able to both swim and walk.

There is a holotype of Aegyptocetus tarfa found in 2002 by a marble cutter of Pietrasanta in a block of Egyptian limestone.[4] The path then ends with a series of casts of fossils belonging to Cynthiacetus.[5]

Cetacean gallery

The cetacean collection was significantly enriched between the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, thanks to then-director Sebastiano Richiardi to create a collection that had at least one specimen for each species of existing cetacean.

The cetacean gallery is a 110-meter long space surmounted by a gabled roof. When the friars still inhabited the Certosa, it was used for drying hay and grains, which were then stored in the numerous silos located at the edge of the structure. The exhibition was organized in 2018 into eight thematic areas containing more than 28 skeletons from the 27 species present in the collection, as well as 11 life-sized models including a baleen, five casts of fossils mostly discovered and studied by the team of the University of Pisa, such as that of Livyatan melvillei as well as from real fossils, such as the holotypes of Balaenula astensis, found in Portacomaro in 1940.[4]

Most are skeletal remains, although there are also preparations preserved in liquid. While this is not the largest in the number of specimens, it has the largest diversity with 27 different species. The gallery contains complete skeletons of Hector's dolphin, White-beaked dolphin, Finless porpoise, and the very rare Andrews' beaked whale; as well as those of the Sei whale and blue whale, the latter purchased, again by Richiardi, in 1900 from the Museum of Natural History of Bergen, in Norway. Also, the museum also houses the only adult skeletons of Humpback whales and North Atlantic right whales present in Italy, the only two Killer Whale skeletons in Italy, the only two complete with beluga, and the only one complete with boreal hyperodon. [6][7] Alongside the collection of current cetaceans, the museum also possesses various finds of fossil cetaceans of various origins and acquisitions. However, a large part of them was donated to the Museum by the Florentine paleontologist Roberto Lawley, such as an individual's remains from Etruridelphis giulii.[4]

There is also a blue whale, and the fin whale. The collection includes the mandible of a sperm whale beached in 1714 in Populonia.[8][6]

Hall of the evolution of man

This hall includes a full-scale reconstruction of a portion of the 31,000-year old painted wall of the Chauvet cave (Ardèche, France).

Mineral gallery

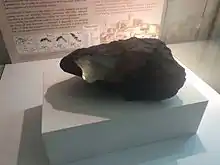

A large collection of minerals from the Tuscan area as well as the largest Italian meteorite: the 48 kg Bagnone’s Octahedrite.

"The Earth between myth and science"

A 9-meter by 5-meter wooden reconstruction of Noah's Ark with 160 animals beside a cyclops and a unicorn.

The biblical myth is contested by descriptive panels, samples of volcanic rocks, and explanations of Earth's origin through evolution.

Dinosaur gallery

In 2020, this gallery is partly under construction. The collection includes, Carnotaurus sastrei, Amargasaurus cazaui, Kritosaurus and a nesting plain of Saltasaurs.

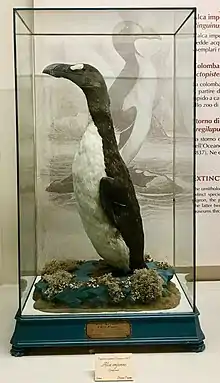

Evolution of birds

19 life-size avian models from the Mesozoic explain the transition from dinosaurs to birds. The museum contains the osteology collections of Sebastiano Richiardi. The bird collection consists of 9,000 mounts, 1,000 skins, 275 skeletons, 1,100 eggs, 800 nests, and 450 anatomical specimens.

Mollusc collections

The museum contains:

- 700 samples collected by Niccolò Gualtieri , which were studied by Carl Linnaeus . Linnaeus used many of these specimens in his tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.

- Samples from Georg Eberhard Rumphius acquired in 1747 by Francesco di Lorena.

Insect collections

The museum contains insects collected by:

History

The museum dates back to the 16th century when the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando I de 'Medici set up a cabinet of curiosities attached to the Giardino dei Semplici.[9]

The direction was entrusted to Luca Ghini, founder and curator of the botanical garden.[10] In 1595, Ferdinando ordered that the various Florentine naturalistic collections was brought into the museum and founded one of the first museums in the world.[9]

The museum was enriched with new collections: in particular, in 1747, Francis I of Lorraine bought an important part of the malacological collection for the museum of the Florentine physician Niccolò Gualtieri, including more than three thousand specimens collected by the Dutch naturalist Georg Eberhard Rumphius.[11]

In the 19th century, the museum had its period of maximum expansion. In 1814, the University of Pisa decided to separate the chairs of scientific teaching, entrusting Gaetano Savi with that of Botany and Giorgio Santi that of zoology, paleontology and geology. This separation of the chairs meant that the museum, which also included the botanical collections under a single direction, was divided into two distinct administrations with greater decision-making autonomy.

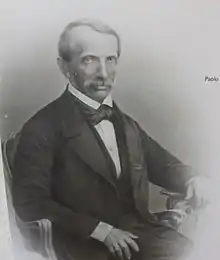

Under the direction of Paolo Savi, the collections were enriched, the exhibition spaces were enlarged, and hundreds of writings were published. Savi called upon the Neapolitan Leopoldo Pilla to fill the museum and this brought a large number of Vesuvian rocks and crystals with him.[12]

The museum was shaken by the world wars. During the Second World War, some of the collections were damaged by Allied bombings.[13]

References

- "Il più grande acquario d'acqua dolce d'Italia" [The largest freshwater aquarium in Italy]. Museo di Storia Naturale dell'Università di Pisa (in Italian). 10 May 2016.

- "Inaugurazione dell'Acquario di Calci" [Inauguration of the Calci Aquarium]. unipi.it (in Italian). 13 May 2016.

- "A Calci il più grande acquario d'acqua dolce" [In Calci the largest freshwater aquarium]. cascinanotizie.it (in Italian). 9 May 2016.

- Bianucci, Giovanni (2014). "CLe collezioni a cetacei fossili del Museo di Storia Naturale dell'Università di Pisa". Museologia Scientifica Memorie. 13: 93–102.

- "Archaeocetes".

- "Catalogo dei Cetacei attuali del Museo di Storia Naturale e del Territorio dell'Università di Pisa, alla Certosa di Calci. Note Osteometriche e Ricerca storica" (PDF). Atti della Società Toscana di Scienze Naturali. 114: 1–22. 2007.

- Cagnolaro, Luigi. "Collections of extant Cetaceans in Italian museums and other scientific institutions. A comparative review". Atti Società Italiana Scienze Naturali, Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano. 153 (2): 145–202. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "Cetaceans".

- Monechi, Simonetta; Rook, Lorenzo (2009). Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze. Le collezioni geologiche e paleontologiche / The Museum of Natural History of the University of Florence. The Geological and Paleontological Collections. ISBN 978-8864531892.

- "Fine 1500: le origini del Museo" [Late 1500s: the origins of the Museum] (in Italian). Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "1600-1700: declino e ascesa" [1600-1700: decline and rise] (in Italian). Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "1800: l'autonomia e la fortuna" [1800: autonomy and luck] (in Italian). Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Il Museo oggi: il miracolo della Certosa" [The Museum today: the miracle of the Certosa] (in Italian). Retrieved 14 October 2020.

External links

Media related to Museo di storia naturale dell'Università di Pisa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Museo di storia naturale dell'Università di Pisa at Wikimedia Commons