Newell Houston Ensley

Newell Houston Ensley (August 23, 1852 – May 23, 1888) was a leader in the Baptist Church and African-American civil rights. He was a professor at Shaw University, Howard University, and Alcorn University.

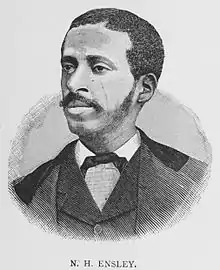

Newell Houston Ensley | |

|---|---|

Ensley in 1887 | |

| Born | August 23, 1852 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | May 23, 1888 (aged 35) |

| Occupation | Professor, musician |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Piper Ensley |

Early life

Newell Houston Ensley was born a slave in Nashville, Tennessee August 23, 1852 to George and Clara Ensley. His family was owned by his mother's father and Ensley was allowed to play with the white children on the farm and to learn to read. While still a child during the American Civil War (1861–1865), Ensley ran away and hid in Union Army camps that were nearby until the Army moved on and he returned to the farm where he received a whipping. In spite of this, Ensley remained on the farm after the war was over and the abolition of slavery. His former master died in 1866, a year after the war ended. Ensley's father died some time earlier, and his step-father did not wish him to attend school. In spite of this, he did attend lessons, one of his teachers was Benjamin Holmes, who later was a member of the Fisk Jubilee Singers.[1]

Career

When Holmes left the school to join the Jubilee Singers on their first tour in 1871, Ensley was appointed in his stead. On top of his teaching duties, Ensley taught the Sunday school. He was also baptized and became a deacon. In February 1871, he entered Roger Williams University where he studied under Daniel W. Phillips. About this time he was licensed to preach. He also became known for his singing.[1] At the same time he attended the six-year classical course Nashville Baptist Institute, receiving a diploma in May 1877.[2] In June 1878 he graduated third in his class from Roger Williams University and entered Newton Theological Seminary in Newton Center, Massachusetts. He graduated three years later as the only black person in a class of seven.[1]

After graduating from Newton he took a position of professor of theology and Latin[1] at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina.[3] One year later he moved to Howard University in Washington, DC. About this time he married. He then moved to Alcorn University in Lorman, Mississippi where he held the title of professor of rhetoric, natural sciences, and vocal music[1] from 1882 until his death in 1888.[3] He was a scholar of Greek, and a noted orator and poet.[1]

Civil rights

Later in his life, Ensley frequently traveled to give talks about African-American issues. In June 1883, he was in Chicago for a Baptist Minister Conference at the Grand Pacific Hotel. Reverend E. O. Taylor and a group of ministers including Ensley went to Race Brothers' oyster house. The restaurant had a rule against serving black people, and Ensley was thrown out in an affair which received national coverage.[4][5] In 1886, he traveled to St. Louis for the First National Convention of Colored Baptists. At that meeting, he spoke out against the poor behavior of certain leaders of the Colored Conventions Movement[6]

Personal life and death

Ensley married Elizabeth Piper Ensley on September 4, 1882, in Boston.[7] They had three children: Roger (born 1883), Charlotte (born 1885), and Jean (March 1888–June 1888).

In 1887, Ensley was in ill health and was travelling and speaking throughout the country.[8] He died in Denver, Colorado on May 23, 1888.[3]

References

- Simmons, William J.; McNeal Turner, Henry (1887). Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. Cleveland, Ohio: Geo. M. Rewell & Company. pp. 361–367.

- "The Nashville Baptist Institute". The Tennessean. Nashville, Tennessee. May 29, 1877. p. 4. Retrieved October 4, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- The Newton Theological Institution: General Catalogue, Andover Newton Theological School, 1912, p. 160.

- "Refused Refreshment". The Inter Ocean. Chicago, Illinois. June 27, 1883. p. 7. Retrieved October 4, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- "A Civil Rights Case in Chicago". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans, Louisiana. June 27, 1883. p. 8. Retrieved October 4, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- "Colored Baptists". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. August 23, 1886. p. 1. Retrieved October 4, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- Massachusetts, Marriage Records, 1840–1915.

- "Social Status of the Negroes". Omaha World-Herald. Omaha, Nebraska). October 6, 1887. p. 1.