Northern Qi

The Northern Qi (simplified Chinese: 北齐; traditional Chinese: 北齊; pinyin: Běi Qí; Wade–Giles: Pei3-Ch'i2), also called Later Qi and Gao Qi, was one of the Northern dynasties of imperial China history and ruled northeastern China from 550 to 577. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Wenxuan, and it was ended following attacks from Northern Zhou.

Qi 齊 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550–577 | |||||||||

Asia in 565 AD, showing the Northern Qi Dynasty and its neighbors | |||||||||

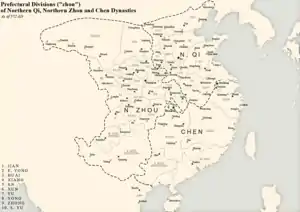

Administrative divisions in 572 AD | |||||||||

| Capital | Yecheng[1] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 550–559 | Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi | ||||||||

• 559–560 | Emperor Fei of Northern Qi | ||||||||

• 560–561 | Emperor Xiaozhao of Northern Qi | ||||||||

• 561–565 | Emperor Wucheng of Northern Qi | ||||||||

• 565–577 | Gao Wei | ||||||||

• 577 | Gao Heng | ||||||||

| Historical era | Northern Dynasties | ||||||||

• Established | 9 June[2] 550 | ||||||||

| 28 February[3] 577 | |||||||||

• Gao Shaoyi's capture by Northern Zhou | 27 July 580[4] | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 557[5] | 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | Chinese coin, Chinese cash | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||

History

Northern Qi was the successor state of the Chinese Xianbei state of Eastern Wei and was founded by Emperor Wenxuan. Emperor Wenxuan had an Han father Gao Huan (specially, he is a Xianbei in cultural conception), and a Xianbei mother, Lou Zhaojun.[6][7] As Eastern Wei's powerful minister Gao Huan was succeeded by his sons Gao Cheng and Gao Yang, who took the throne from Emperor Xiaojing of Eastern Wei in 550 and established Northern Qi as Emperor Wenxuan.

Northern Qi was the strongest state out of the three main states (the other two being Northern Zhou state and Chen Dynasty) in China when Chen was established. Northern Qi however was plagued by violence and/or incompetent emperors (in particular Houzhu),[8] corrupt officials, and deteriorating armies. In 571, an important official who guide the emperors Emperor Wucheng and Houzhu, He Shikai, was killed. Houzhu attempted to strengthen the power of throne, instead he triggered a series of purges that became violent in late 573.[8]

In 577, Northern Qi was assaulted by Northern Zhou, a northwestern kingdom with poorer resources.[9] The Northern Qi, with ineffective leadership, quickly disintegrated within a month, with large scale defections of court and military personnel.[10] Both Houzhu and the last emperor Youzhu were captured, and both died in late 577. Emperor Wenxuan's son Gao Shaoyi, the Prince of Fanyang, under protection by Tujue, later declared himself the emperor of Northern Qi in exile, but was turned over by Tujue to Northern Zhou in 580 and exiled to modern Sichuan. It is a matter of dispute whether Gao Shaoyi should properly be considered a Northern Qi emperor, but in any case the year 577 is generally considered by historians as the ending date for Northern Qi.

Emperors

| Posthumous Name | Personal Name | Period of Reign | Era Names |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wenxuan | Gao Yang | 550-559 | Tianbao (天保) 550-559 |

| – | Gao Yin | 559-560 | Qianming (乾明) 560 |

| Xiaozhao | Gao Yan | 560-561 | Huangjian (皇建) 560-561 |

| Wucheng | Gao Zhan | 561-565 | Taining (太寧) 561-562 Heqing (河清) 562-565 |

| – | Gao Wei | 565-577[note 1] | Tiantong (天統) 565-569 Wuping (武平) 570-576 Longhua (隆化) 576 |

| – | Gao Heng | 577[note 2][note 3] | Chengguang (承光) 577 |

Emperors family tree

| Emperors family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Northern Qi arts

Northern Qi ceramics mark a revival of Chinese ceramic art, following the disastrous invasions and the social chaos of the 4th century.[13] Northern Qi tombs have revealed some beautiful artifacts, such as porcelain with splashed green designs, previously thought to have been developed under the Tang dynasty.[11]

Markedly unique from earlier depictions of the Buddha, Northern Qi statues tend to be smaller, around three feet tall, and columnar in shape.[14]

A jar has been found in a Northern Qi tomb, which was closed in 576, and is considered as a precursor of the Tang Sancai style of ceramics.[15]

Also, brown glazed wares designed with Sasanian-style figures have been found in these tombs.[11] These works suggest a strong cosmopolitanism and intense exchanges with Western Asia, which are also visible in metalworks and relief sculptures across China during this period.[11] Cosmopolitanism was therefore already current during the Northern Qi period in the 6th century, even before the advent of the notoriously cosmopolitan Tang dynasty, and was often associated with Buddhism.[11][16]

Identity

The Northern Qi, although founded by a ruler of mixed Han/Xianbei origin, strongly asserted their Xianbei ethnic cultural identity. They regarded surviving ethnic Tuoba (themselves also Xianbei) and non-Chinese of the Northern Wei court and as well as literati of all ethnicities as near Chinese, referring to them as Han'er or Chinese kids (漢兒).[10] However they made use of Chinese and sometimes Central Asian courtiers.[17] While some Qi elite families had expressed strongly anti-Chinese sentiments due to unclear reasons, they may also lay claim to Chinese elite origin.[8] Emperor Wenxuan's father Gao Huan himself, who was reported as having said to his soldiers in the Xianbei language: "You guys are our proud military men and the lowly Chinese are just your working slaves",[18][19] was descended from the Chinese Gao family of Bohai (渤海高氏) in what is now modern Hebei.[20] He had become Xianbeified as his family had lived for some time in Inner Mongolia after his grandfather was relocated from Bohai.[21][22]

Religions

A Chinese scholar translated the Buddhist text Nirvana Sutra text into a Turkic language during this era. Some Zoroastrianism influences that went into previous states continued onto the state of Northern Qi court, such as the love for Persian dogs (sacred in Zoroastrianism) as they were taken as pets by nobles and eunuchs. The Chinese utilized a number of Persian artifacts and products.[23]

Northern Qi Great Wall

Faced with the threat of the Göktürks from the north, from 552 to 556 the Qi built up to 3,000 li (about 1,600 kilometres (990 mi)) of wall from Shanxi to the sea at Shanhai Pass.[24] In 552, the Great Wall was built, starting at the northwest frontier, starting from Lishi (离石) and expanding towards west Shuoxian (朔县), with total length of over 400 kilometers.[25] In 555, Emperor Wenquan commanded to repair and rebuild the existing Great Wall of Northern Wei. Over the course of the year 555 alone, 1.8 million men were mobilized to build the Juyong Pass and extend its wall by 450 kilometres (280 mi) through Datong to the eastern banks of the Yellow River. In 557 a secondary wall was built inside the main one, starting from east of Pianguan (偏关), passing Yanmen Pass, Pingxing (平型) Pass, and continuing to Xiaguan (下关) in Shanxi Province. In 563, Emperor Wucheng built a section of frontier wall along the Taihang Mountains on the border of Shanxi and Hebei provinces. These walls were built quickly from local earth and stones or formed by natural barriers. Two stretches of the stone-and-earth Qi wall still stand in Shanxi today, measuring 3.3 metres (11 ft) wide at their bases and 3.5 metres (11 ft) high on average. In 577 the Northern Zhou conquered the Northern Qi and in 580 made repairs to the existing Qi walls. The route of the Qi and Zhou walls would be mostly followed by the later Ming wall west of Gubeikou.

See also

Notes

- Gao Wei's cousin Gao Yanzong the Prince of Ande (Gao Cheng's son) briefly declared himself emperor around the new year 577 after the soldiers guarding the city of Jinyang (晉陽, in modern Taiyuan, Shanxi) demanded that he claim the title when Gao Wei abandoned Jinyang. Gao Yanzong, however, was almost immediately defeated and captured by Northern Zhou troops, and therefore is generally not considered a true Northern Qi emperor.

- In 577, Gao Wei, then with the title Taishang Huang (retired emperor), tried to issue an edict on his son's behalf yielding the throne to his uncle (Gao Huan's son) Gao Jie (高湝) the Prince of Rencheng, but the officials he sent to deliver the edict to Gao Jie surrendered to Northern Zhou rather than delivering the edict to Gao Jie, who was subsequently also captured by Northern Zhou troops. It is questionable whether Gao Jie was even aware of the edict, and in any case, Gao Jie never used imperial title.

- As noted above, Emperor Wenxuan's son Gao Shaoyi tried to establish a Northern Qi court in exile on Tujue's territory, but was not successful in his efforts in recapturing formerly Northern Qi territory, and was eventually turned over by Tujue to Northern Zhou. Most historians do not consider him a true Northern Qi emperor, although the matter remains in controversy.

References

Citations

- Gernet, Jacques (31 May 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 193–. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 163.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 173.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 174.

- Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 129. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 1170959.

- Lee (2007). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E.-618 C.E. M.E. Sharpe. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-7656-4182-3.

- Lily Xiao Hong Lee; A.D. Stefanowska; Sue Wiles (26 March 2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. - 618 C.E. Routledge. pp. 314–. ISBN 978-1-317-47591-0.

- Andrew Eisenberg (23 January 2008). Kingship in Early Medieval China. BRILL. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-90-474-3230-2.

- Andrew Eisenberg (23 January 2008). Kingship in Early Medieval China. BRILL. p. 93. ISBN 978-90-474-3230-2.

- Andrew Eisenberg (23 January 2008). Kingship in Early Medieval China. BRILL. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-90-474-3230-2.

- The arts of China by Michael Sullivan p.120

- Notice of the Metropolitan Museum of Art permanent exhibition.

- The arts of China by Michael Sullivan p.19ff

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art: guide to the collection. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- Chinese glazes: their origins, chemistry, and recreation by Nigel Wood p.200

- China between empires: the northern and southern dynasties by Mark Edward Lewis p.168

- Andrew Eisenberg (1 January 2008). Kingship in Early Medieval China. BRILL. p. 99. ISBN 978-90-04-16381-2.

- Prof. Albert Dien. "THE STIRRUP AND ITS EFFECT ON CHINESE MILITARY HISTORY". Archived from the original on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2016-06-18.

- Albert E. Dien (2007). Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8.

- Victor Cunrui Xiong (4 December 2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval China. Scarecrow Press. pp. 171–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6258-6.

- Lily Xiao Hong Lee; A.D. Stefanowska; Sue Wiles (26 March 2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. - 618 C.E. Routledge. pp. 314–. ISBN 978-1-317-47591-0.

- Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E.-618 C.E. M.E. Sharpe. 2007. pp. 314–. ISBN 978-0-7656-4182-3.

- Cunren Liu (1976). Angela Schottenhammer (ed.). Selected papers from the Hall of harmonious wind. Brill Archive. p. 14. ISBN 90-04-04492-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Tackett, Nicholas (2008). "The Great Wall and Conceptualizations of the Border Under the Northern Song". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. The Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies. 38 (38): 99–138. doi:10.1353/sys.0.0032 (inactive 2021-01-17). JSTOR 23496246.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- "The Great Wall of the Northern Qi Dynasty". China Highlights. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

Sources

- Book of Northern Qi.

- History of Northern Dynasties.

- Zizhi Tongjian.

External links

Media related to Northern Qi Dynasty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Northern Qi Dynasty at Wikimedia Commons