One-way speed of light

When using the term 'the speed of light' it is sometimes necessary to make the distinction between its one-way speed and its two-way speed. The "one-way" speed of light, from a source to a detector, cannot be measured independently of a convention as to how to synchronize the clocks at the source and the detector. What can however be experimentally measured is the round-trip speed (or "two-way" speed of light) from the source to the detector and back again. Albert Einstein chose a synchronization convention (see Einstein synchronization) that made the one-way speed equal to the two-way speed. The constancy of the one-way speed in any given inertial frame is the basis of his special theory of relativity, although all experimentally verifiable predictions of this theory do not depend on that convention.[1][2]

Experiments that attempted to directly probe the one-way speed of light independent of synchronization have been proposed, but none has succeeded in doing so.[3] Those experiments directly establish that synchronization with slow clock-transport is equivalent to Einstein synchronization, which is an important feature of special relativity. Though those experiments don't directly establish the isotropy of the one-way speed of light, because it was shown that slow clock-transport, the laws of motion, and the way inertial reference frames are defined, already involve the assumption of isotropic one-way speeds and thus are conventional as well.[4] In general, it was shown that these experiments are consistent with anisotropic one-way light speed as long as the two-way light speed is isotropic.[1][5]

The 'speed of light' in this article refers to the speed of all electromagnetic radiation in vacuum.

The two-way speed

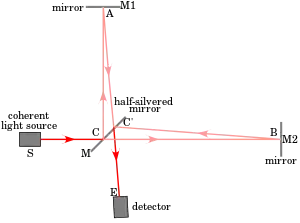

The two-way speed of light is the average speed of light from one point, such as a source, to a mirror and back again. Because the light starts and finishes in the same place only one clock is needed to measure the total time, thus this speed can be experimentally determined independently of any clock synchronization scheme. Any measurement in which the light follows a closed path is considered a two-way speed measurement.

Many tests of special relativity such as the Michelson–Morley experiment and the Kennedy–Thorndike experiment have shown within tight limits that in an inertial frame the two-way speed of light is isotropic and independent of the closed path considered. Isotropy experiments of the Michelson–Morley type do not use an external clock to directly measure the speed of light, but rather compare two internal frequencies or clocks. Therefore, such experiments are sometimes called "clock anisotropy experiments", since every arm of a Michelson interferometer can be seen as a light clock having a specific rate, whose relative orientation dependences can be tested.[6]

Since 1983 the metre has been defined as the distance traveled by light in vacuum in 1⁄299,792,458 second.[7] This means that the speed of light can no longer be experimentally measured in SI units, but the length of a meter can be compared experimentally against some other standard of length.

The one-way speed

Although the average speed over a two-way path can be measured, the one-way speed in one direction or the other is undefined (and not simply unknown), unless one can define what is "the same time" in two different locations. To measure the time that the light has taken to travel from one place to another it is necessary to know the start and finish times as measured on the same time scale. This requires either two synchronized clocks, one at the start and one at the finish, or some means of sending a signal instantaneously from the start to the finish. No instantaneous means of transmitting information is known. Thus the measured value of the average one-way speed is dependent on the method used to synchronize the start and finish clocks. This is a matter of convention. The Lorentz transformation is defined such that the one-way speed of light will be measured to be independent of the inertial frame chosen.[8]

Some authors such as Mansouri and Sexl (1977)[9][10] as well as Will (1992)[11] argued that this problem doesn't affect measurements of the isotropy of the one-way speed of light, for instance, due to direction dependent changes relative to a "preferred" (aether) frame Σ. They based their analysis on a specific interpretation of the RMS test theory in relation to experiments in which light follows a unidirectional path and to slow clock-transport experiments. Will agreed that it is impossible to measure the one-way speed between two clocks using a time-of-flight method without synchronization scheme, though he argued: "...a test of the isotropy of the speed between the same two clocks as the orientation of the propagation path varies relative to Σ should not depend on how they were synchronized...". He added that aether theories can only be made consistent with relativity by introducing ad hoc hypotheses.[11] In more recent papers (2005, 2006) Will referred to those experiments as measuring the "isotropy of light speed using one-way propagation".[6][12]

However, others such as Zhang (1995, 1997)[1][13] and Anderson et al. (1998)[2] showed this interpretation to be incorrect. For instance, Anderson et al. pointed out that the conventionality of simultaneity must already be considered in the preferred frame, so all assumptions concerning the isotropy of the one-way speed of light and other velocities in this frame are conventional as well. Therefore, RMS remains a useful test theory to analyze tests of Lorentz invariance and the two-way speed of light, though not of the one-way speed of light. They concluded :"...one cannot hope even to test the isotropy of the speed of light without, in the course of the same experiment, deriving a one-way numerical value at least in principle, which then would contradict the conventionality of synchrony."[2] Using generalizations of Lorentz transformations with anisotropic one-way speeds, Zhang and Anderson pointed out that all events and experimental results compatible with the Lorentz transformation and the isotropic one-way speed of light must also be compatible with transformations preserving two-way light speed constancy and isotropy, while allowing anisotropic one-way speeds.

Synchronization conventions

The way in which distant clocks are synchronized can have an effect on all time-related measurements over distance, such as speed or acceleration measurements. In isotropy experiments, simultaneity conventions are often not explicitly stated but are implicitly present in the way coordinates are defined or in the laws of physics employed.[2]

Einstein convention

This method synchronizes distant clocks in such a way that the one-way speed of light becomes equal to the two-way speed of light. If a signal sent from A at time is arriving at B at time and coming back to A at time , then the following convention applies:

- .

The details of this method, and the conditions that assure its consistency are discussed in Einstein synchronization.

Slow clock-transport

It is easily demonstrated that if two clocks are brought together and synchronized, then one clock is moved rapidly away and back again, the two clocks will no longer be synchronized. This effect is due to time dilation. This was measured in a variety of tests and is related to the twin paradox.[14][15]

However, if one clock is moved away slowly in frame S and returned the two clocks will be very nearly synchronized when they are back together again. The clocks can remain synchronized to an arbitrary accuracy by moving them sufficiently slowly. If it is taken that, if moved slowly, the clocks remain synchronized at all times, even when separated, this method can be used to synchronize two spatially separated clocks. In the limit as the speed of transport tends to zero, this method is experimentally and theoretically equivalent to the Einstein convention.[4] Though the effect of time dilation on those clocks cannot be neglected anymore when analyzed in another relatively moving frame S'. This explains why the clocks remain synchronized in S, whereas they are not synchronized anymore from the viewpoint of S', establishing relativity of simultaneity in agreement with Einstein synchronization.[16] Therefore, testing the equivalence between these clock synchronization schemes is important for special relativity, and some experiments in which light follows a unidirectional path have proven this equivalence to high precision.

Non-standard synchronizations

As demonstrated by Hans Reichenbach and Adolf Grünbaum, Einstein synchronization is only a special case of a broader synchronization scheme, which leaves the two-way speed of light invariant, but allows for different one-way speeds. The formula for Einstein synchronization is modified by replacing ½ with ε:[4]

ε can have values between 0 and 1. It was shown that this scheme can be used for observationally equivalent reformulations of the Lorentz transformation, see Generalizations of Lorentz transformations with anisotropic one-way speeds.

As required by the experimentally proven equivalence between Einstein synchronization and slow clock-transport synchronization, which requires knowledge of time dilation of moving clocks, the same non-standard synchronisations must also affect time dilation. It was indeed pointed out that time dilation of moving clocks depends on the convention for the one-way velocities used in its formula.[17] That is, time dilation can be measured by synchronizing two stationary clocks A and B, and then the readings of a moving clock C are compared with them. Changing the convention of synchronization for A and B makes the value for time dilation (like the one-way speed of light) directional dependent. The same conventionality also applies to the influence of time dilation on the Doppler effect.[18] Only when time dilation is measured on closed paths, it is not conventional and can unequivocally be measured like the two-way speed of light. Time dilation on closed paths was measured in the Hafele–Keating experiment and in experiments on the time dilation of moving particles such as Bailey et al. (1977).[19] Thus the so-called twin paradox occurs in all transformations preserving the constancy of the two-way speed of light.

Inertial frames and dynamics

It was argued against the conventionality of the one-way speed of light that this concept is closely related to dynamics, the laws of motion and inertial reference frames.[4] Salmon described some variations of this argument using momentum conservation, from which it follows that two equal bodies at the same place which are equally accelerated in opposite directions, should move with the same one-way velocity.[20] Similarly, Ohanian argued that inertial reference frames are defined so that Newton's laws of motion hold in first approximation. Therefore, since the laws of motion predict isotropic one-way speeds of moving bodies with equal acceleration, and because of the experiments demonstrating the equivalence between Einstein synchronization and slow clock-transport synchronization, it appears to be required and directly measured that the one-way speed of light is isotropic in inertial frames. Otherwise, both the concept of inertial reference frames and the laws of motion must be replaced by much more complicated ones involving anisotropic coordinates.[21][22]

However, it was shown by others that this is principally not in contradiction with the conventionality of the one-way speed of light.[4] Salmon argued that momentum conservation in its standard form assumes isotropic one-way speed of moving bodies from the outset. So it involves practically the same convention as in the case of isotropic one-way speed of light, thus using this as an argument against light speed conventionality would be circular.[20] And in response to Ohanian, both Macdonald and Martinez argued that even though the laws of physics become more complicated with non-standard synchrony, they still are a consistent way to describe the phenomena. They also argued that it's not necessary to define inertial frames in terms of Newton's laws of motion, because other methods are possible as well.[23][24] In addition, Iyer and Prabhu distinguished between "isotropic inertial frames" with standard synchrony and "anisotropic inertial frames" with non-standard synchrony.[25]

Experiments which appear to measure the one-way speed of light

The Greaves, Rodriguez and Ruiz-Camacho experiment

In the October 2009 issue of the American Journal of Physics Greaves, Rodriguez and Ruiz-Camacho proposed a new method of measurement of the one-way speed of light.[26] In the June 2013 issue of the American Journal of Physics Hankins, Rackson and Kim repeated the Greaves et al. experiment intending to obtain with greater accuracy the one way speed of light.[27] This experiment assumed that the signal return path to the measuring device has a constant delay, independent of the end point of the light flight path, allowing measurement of the time of flight in a single direction.

J. Finkelstein showed that the Greaves et al. experiment actually measures the round trip (two-way) speed of light.[28]

Experiments in which light follows a unidirectional path

Many experiments intended to measure the one-way speed of light, or its variation with direction, have been (and occasionally still are) performed in which light follows a unidirectional path.[29] Claims have been made that those experiments have measured the one-way speed of light independently of any clock synchronisation convention, but they have all been shown to actually measure the two-way speed, because they are consistent with generalized Lorentz transformations including synchronizations with different one-way speeds on the basis of isotropic two-way speed of light (see sections the one-way speed and generalized Lorentz transformations).[1]

These experiments also confirm agreement between clock synchronization by slow transport and Einstein synchronization.[2] Even though some authors argued that this is sufficient to demonstrate the isotropy of the one-way speed of light,[10][11] it has been shown that such experiments cannot, in any meaningful way, measure the (an)isotropy of the one way speed of light unless inertial frames and coordinates are defined from the outset so that space and time coordinates as well as slow clock-transport are described isotropically[2] (see sections inertial frames and dynamics and the one-way speed). Regardless of those different interpretations, the observed agreement between those synchronization schemes is an important prediction of special relativity, because this requires that transported clocks undergo time dilation (which itself is synchronization dependent) when viewed from another frame (see sections Slow clock-transport and Non-standard synchronizations).

The JPL experiment

This experiment, carried out in 1990 by the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, measured the time of flight of light signals through a fibre optic link between two hydrogen maser clocks.[30] In 1992 the experimental results were analysed by Clifford Will who concluded that the experiment did actually measure the one-way speed of light.[11]

In 1997 the experiment was re-analysed by Zhang who showed that, in fact, only the two-way speed had been measured.[31]

Rømer's measurement

The first experimental determination of the speed of light was made by Ole Christensen Rømer. It may seem that this experiment measures the time for light to traverse part of the Earth's orbit and thus determines its one-way speed, however, this experiment was carefully re-analysed by Zhang, who showed that the measurement does not measure the speed independently of a clock synchronization scheme but actually used the Jupiter system as a slowly-transported clock to measure the light transit times.[32]

The Australian physicist Karlov also showed that Rømer actually measured the speed of light by implicitly making the assumption of the equality of the speeds of light back and forth.[33][34]

Other experiments comparing Einstein synchronization with slow clock-transport synchronization

| Experiments | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moessbauer rotor experiments | 1960s | Gamma radiation was sent from the rear of a rotating disc into its center. It was expected that anisotropy of the speed of light would lead to Doppler shifts. | |

| Vessot et al.[35] | 1980 | Comparing the times-of-flight of the uplink- and downlink signal of Gravity Probe A. | |

| Riis et al.[36] | 1988 | Comparing the frequency of two-photon absorption in a fast particle beam, whose direction was changed relative to the fixed stars, with the frequency of a resting absorber. | |

| Nelson et al.[37] | 1992 | Comparing the frequencies of a hydrogen maser clock and laser light pulses. The path length was 26 km. | |

| Wolf & Petit[38] | 1997 | Clock comparisons between hydrogen maser clocks on the ground and cesium and rubidium clocks on board 25 GPS satellites. |

Experiments that can be done on the one-way speed of light

Although experiments cannot be done in which the one-way speed of light is measured independently of any clock synchronization scheme, it is possible to carry out experiments that measure a change in the one-way speed of light due, for example, to the motion of the source. Such experiments are the De Sitter double star experiment (1913), conclusively repeated in the X-ray spectrum by K. Brecher in 1977;[39] or the terrestrial experiment by Alväger, et al. (1963);[40] they show that, when measured in an inertial frame, the one-way speed of light is independent of the motion of the source within the limits of experimental accuracy. In such experiments the clocks may be synchronized in any convenient way, since it is only a change of speed that is being measured.

Observations of the arrival of radiation from distant astronomical events have shown that the one-way speed of light does not vary with frequency, that is, there is no vacuum dispersion of light.[41] Similarly, differences in the one-way propagation between left- and right-handed photons, leading to vacuum birefringence, were excluded by observation of the simultaneous arrival of distant star light.[42] For current limits on both effects, often analyzed with the Standard-Model Extension, see Vacuum dispersion and Vacuum birefringence.

Experiments on two-way and one-way speeds using the Standard-Model Extension

While the experiments above were analyzed using generalized Lorentz transformations as in the Robertson–Mansouri–Sexl test theory, many modern tests are based on the Standard-Model Extension (SME). This test theory includes all possible Lorentz violations not only of special relativity, but of the Standard Model and General relativity as well. Regarding the isotropy of the speed of light, both two-way and one-way limits are described using coefficients (3x3 matrices):[43]

- representing anisotropic shifts in the two-way speed of light,[44][45]

- representing anisotropic differences in the one-way speed of counterpropagating beams along an axis,[44][45]

- representing isotropic (orientation independent) shifts in the one-way phase velocity of light.[46]

A series of experiments have been (and still are) performed since 2002 testing all of those coefficients using, for instance, symmetric and asymmetric optical resonators. No Lorentz violations have been observed as of 2013, providing current upper limits for Lorentz violations: , , and . For details and sources see Modern searches for Lorentz violation#Speed of light.

However, the partially conventional character of those quantities was demonstrated by Kostelecky et al, pointing out that such variations in the speed of light can be removed by suitable coordinate transformations and field redefinitions. Though this doesn't remove the Lorentz violation per se, since such a redefinition only transfers the Lorentz violation from the photon sector to the matter sector of SME, thus those experiments remain valid tests of Lorentz invariance violation.[43] There are one-way coefficients of the SME that cannot be redefined into other sectors, since different light rays from the same distance location are directly compared with each other, see the previous section.

Theories in which the one-way speed of light is not equal to the two-way speed

Lorentz ether theory

In 1904 and 1905, Hendrik Lorentz and Henri Poincaré proposed a theory which explained this result as being due to the effect of motion through the aether on the lengths of physical objects and the speed at which clocks ran. Due to motion through the aether objects would shrink along the direction of motion and clocks would slow down. Thus, in this theory, slowly transported clocks do not, in general, remain synchronized although this effect cannot be observed. The equations describing this theory are known as the Lorentz transformations. In 1905 these transformations became the basic equations of Einstein's special theory of relativity which proposed the same results without reference to an aether.

In the theory, the one-way speed of light is principally only equal to the two-way speed in the aether frame, though not in other frames due to the motion of the observer through the aether. However, the difference between the one-way and two-way speeds of light can never be observed due to the action of the aether on the clocks and lengths. Therefore, the Poincaré-Einstein convention is also employed in this model, making the one-way speed of light isotropic in all frames of reference.

Even though this theory is experimentally indistinguishable from special relativity, Lorentz's theory is no longer used for reasons of philosophical preference and because of the development of general relativity.

Generalizations of Lorentz transformations with anisotropic one-way speeds

A sychronisation scheme proposed by Reichenbach and Grünbaum, which they called ε-synchronization, was further developed by authors such as Edwards (1963),[47] Winnie (1970),[17] Anderson and Stedman (1977), who reformulated the Lorentz transformation without changing its physical predictions.[1][2] For instance, Edwards replaced Einstein's postulate that the one-way speed of light is constant when measured in an inertial frame with the postulate:

The two way speed of light in a vacuum as measured in two (inertial) coordinate systems moving with constant relative velocity is the same regardless of any assumptions regarding the one-way speed.[47]

So the average speed for the round trip remains the experimentally verifiable two-way speed, whereas the one-way speed of light is allowed to take the form in opposite directions:

κ can have values between 0 and 1. In the extreme as κ approaches 1, light might propagate in one direction instantaneously, provided it takes the entire round-trip time to travel in the opposite direction. Following Edwards and Winnie, Anderson et al. formulated generalized Lorentz transformations for arbitrary boosts of the form:[2]

(with κ and κ' being the synchrony vectors in frames S and S', respectively). This transformation indicates the one-way speed of light is conventional in all frames, leaving the two-way speed invariant. κ=0 means Einstein synchronization which results in the standard Lorentz transformation. As shown by Edwards, Winnie and Mansouri-Sexl, by suitable rearrangement of the synchrony parameters even some sort of "absolute simultaneity" can be achieved, in order to simulate the basic assumption of Lorentz ether theory. That is, in one frame the one-way speed of light is chosen to be isotropic, while all other frames take over the values of this "preferred" frame by "external synchronization".[9]

All predictions derived from such a transformation are experimentally indistinguishable from those of the standard Lorentz transformation; the difference is only that the defined clock time varies from Einstein's according to the distance in a specific direction.[48]

Test theories

A number of theories have been developed to allow assessment of the degree to which experimental results differ from the predictions of relativity. These are known as test theories and include the Robertson and Mansouri-Sexl[9] (RMS) theories. To date, all experimental results agree with special relativity within the experimental uncertainty.

Another test theory is the Standard-Model Extension (SME). It employs a broad variety of coefficients indicating Lorentz symmetry violations in special relativity, general relativity, and the Standard Model. Some of those parameters indicate anisotropies of the two-way and one-way speed of light. However, it was pointed out that such variations in the speed of light can be removed by suitable redefinitions of the coordinates and fields employed. Though this doesn't remove Lorentz violations per se, it only shifts their appearance from the photon sector into the matter sector of SME (see above Experiments on two-way and one-way speeds using the Standard-Model Extension.[43]

References

- Yuan-Zhong Zhang (1997). Special Relativity and Its Experimental Foundations. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-2749-4.

- Anderson, R.; Vetharaniam, I.; Stedman, G. E. (1998), "Conventionality of synchronisation, gauge dependence and test theories of relativity", Physics Reports, 295 (3–4): 93–180, Bibcode:1998PhR...295...93A, doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(97)00051-3

- Michael Tooley (2000). Time, tense, and causation. Oxford University Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-19-825074-6.

- Janis, Allen (2010). "Conventionality of Simultaneity". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Jong-Ping Hsu; Yuan-Zhong Zhang (2001). Lorentz and Poincaré Invariance: 100 Years of Relativity. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-4721-8.

- Will, C.M (2005). "Special Relativity: A Centenary Perspective". In T. Damour; O. Darrigol; B. Duplantier; V. Rivasseau (eds.). Poincare Seminar 2005. Basel: Birkhauser (published 2006). pp. 33–58. arXiv:gr-qc/0504085. Bibcode:2006eins.book...33W. doi:10.1007/3-7643-7436-5_2. ISBN 978-3-7643-7435-8. S2CID 17329576.

- 17th General Conference on Weights and Measures (1983), Resolution 1,

- Zhang (1997), p 24

- Mansouri R.; Sexl R.U. (1977). "A test theory of special relativity. I: Simultaneity and clock synchronization". Gen. Rel. Gravit. 8 (7): 497–513. Bibcode:1977GReGr...8..497M. doi:10.1007/BF00762634. S2CID 67852594.

- Mansouri R.; Sexl R.U. (1977). "A test theory of special relativity: II. First order tests". Gen. Rel. Gravit. 8 (7): 515–524. Bibcode:1977GReGr...8..515M. doi:10.1007/BF00762635. S2CID 121525782.

- Will, Clifford M. (1992). "Clock synchronization and isotropy of the one-way speed of light". Physical Review D. 45 (2): 403–411. Bibcode:1992PhRvD..45..403W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.45.403. PMID 10014389.

- Will, C.M. (2006). "The Confrontation between General Relativity and Experiment". Living Rev. Relativ. 9 (1): 12. arXiv:gr-qc/0510072. Bibcode:2006LRR.....9....3W. doi:10.12942/lrr-2006-3. PMC 5256066. PMID 28179873.

- Zhang, Yuan Zhong (1995). "Test theories of special relativity". General Relativity and Gravitation. 27 (5): 475–493. Bibcode:1995GReGr..27..475Z. doi:10.1007/BF02105074. S2CID 121455464.

- Hafele, J. C.; Keating, R. E. (July 14, 1972). "Around-the-World Atomic Clocks: Predicted Relativistic Time Gains". Science. 177 (4044): 166–168. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..166H. doi:10.1126/science.177.4044.166. PMID 17779917. S2CID 10067969.

- C.O. Alley, in NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Proc. of the 13th Ann. Precise Time and Time Interval (PTTI) Appl. and Planning Meeting, p. 687-724, 1981, available online Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- Giulini, Domenico (2005). "Synchronization by slow clock-transport". Special Relativity: A First Encounter. 100 years since Einstein. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0191620866. Special Relativity: A First Encounter at Google Books

- Winnie, J. A. A. (1970). "Special Relativity without One Way Velocity Assumptions". Philosophy of Science. 37 (2): 81–99, 223–38. doi:10.1086/288296. JSTOR 186029. S2CID 224835703.

- Debs, Talal A.; Redhead, Michael L. G. (1996). "The twin "paradox" and the conventionality of simultaneity". American Journal of Physics. 64 (4): 384–392. Bibcode:1996AmJPh..64..384D. doi:10.1119/1.18252.

- Bailey; et al. (1977). "Measurements of relativistic time dilatation for positive and negative muons in a circular orbit". Nature. 268 (5618): 301–305. Bibcode:1977Natur.268..301B. doi:10.1038/268301a0. S2CID 4173884.

- Wesley C. Salmon (1977). "The Philosophical Significance of the One-Way Speed of Light". Noûs. 11 (3): 253–292. doi:10.2307/2214765. JSTOR 221476.

- Ohanian, Hans C. (2004). "The role of dynamics in the synchronization problem". American Journal of Physics. 72 (2): 141–148. Bibcode:2004AmJPh..72..141O. doi:10.1119/1.1596191.

- Ohanian, Hans C. (2005). "Reply to "Comment(s) on 'The role of dynamics in the synchronization problem'," by A. Macdonald and A. A. Martínez". American Journal of Physics. 73 (5): 456–457. Bibcode:2005AmJPh..73..456O. doi:10.1119/1.1858449.

- Martínez, Alberto A. (2005). "Conventions and inertial reference frames" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 73 (5): 452–454. Bibcode:2005AmJPh..73..452M. doi:10.1119/1.1858446. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-02.

- MacDonald, Alan (2004). "Comment on "The role of dynamics in the synchronization problem," by Hans C. Ohanian" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 73 (5): 454–455. Bibcode:2005AmJPh..73..454M. doi:10.1119/1.1858448.

- Iyer, Chandru; Prabhu, G. M. (2010). "A constructive formulation of the one-way speed of light". American Journal of Physics. 78 (2): 195–203. arXiv:1001.2375. Bibcode:2010AmJPh..78..195I. doi:10.1119/1.3266969. S2CID 119218000.

- Greaves, E. D.; Rodríguez, An Michel; Ruiz-Camacho, J. (2009), "A one-way speed of light experiment", American Journal of Physics, 77 (10): 894–896, Bibcode:2009AmJPh..77..894G, doi:10.1119/1.3160665

- Hankins A.; Rackson C.; Kim W. J. (2013), "Photon charge experiment", Am. J. Phys., 81 (6): 436–441, Bibcode:2013AmJPh..81..436H, doi:10.1119/1.4793593

- Finkelstein, J. (2010), "One-way speed of light?", American Journal of Physics, 78 (8): 877, arXiv:0911.3616, Bibcode:2009arXiv0911.3616F, doi:10.1119/1.3364868

- Roberts, Schleif (2006): Relativity FAQ, One-Way Tests of Light-Speed Isotropy

- Krisher; et al. (1990). "Test of the isotropy of the one-way speed of light using hydrogen-maser frequency standards". Physical Review D. 42 (2): 731–734. Bibcode:1990PhRvD..42..731K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.42.731. PMID 10012893.

- Zhang (1997), pp. 148–150

- Zhang (1997), pp. 91-94

- Karlov L (1970). "Does Römer's method yield a unidirectional speed of light?". Australian Journal of Physics. 23: 243–253. Bibcode:1970AuJPh..23..243K. doi:10.1071/PH700243 (inactive 2021-01-17).CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Will, Clifford M.; Matvejev, O. V. (2011). "Simulation of Kinematics of Special Theory of Relativity". arXiv:1201.1828 [physics.gen-ph].

- Vessot; et al. (1980). "Test of relativistic gravitation with a space-borne hydrogen maser". Physical Review Letters. 45 (29): 2081–2084. Bibcode:1980PhRvL..45.2081V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.2081.

- Riis; et al. (1988). "Test of the Isotropy of the speed of light using fast-beam laser spectroscopy". Physical Review Letters. 60 (11): 81–84. Bibcode:1988PhRvL..60...81R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.60.81. PMID 10038204.

- Nelson; et al. (1992). "Experimental comparison of time synchronization techniques by means of light signals and clock transport on the rotating earth" (PDF). Proceedings of the 24th PTTI Meeting. 24: 87–104. Bibcode:1993ptti.meet...87N.

- Wolf, Peter; Petit, Gérard (1997). "Satellite test of special relativity using the global positioning system". Physical Review A. 56 (6): 4405–4409. Bibcode:1997PhRvA..56.4405W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.56.4405.

- Brecher, K. (1977), "Is the speed of light independent of the velocity of the source", Physical Review Letters, 39 (17): 1051–1054, Bibcode:1977PhRvL..39.1051B, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.39.1051, S2CID 26217047.

- Alväger, T.; Nilsson, A.; Kjellman, J. (1963), "A Direct Terrestrial Test of the Second Postulate of Special Relativity", Nature, 197 (4873): 1191, Bibcode:1963Natur.197.1191A, doi:10.1038/1971191a0, S2CID 4190242

- Amelino-Camelia, G (2009). "Astrophysics: Burst of support for relativity". Nature. 462 (7271): 291–292. Bibcode:2009Natur.462..291A. doi:10.1038/462291a. PMID 19924200. S2CID 205051022. Lay summary – Nature (19 November 2009).

- Laurent; et al. (2011). "Constraints on Lorentz Invariance Violation using integral/IBIS observations of GRB041219A". Physical Review D. 83 (12): 121301. arXiv:1106.1068. Bibcode:2011PhRvD..83l1301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.83.121301. S2CID 53603505.

- Kostelecký, V. Alan; Mewes, Matthew (2002). "Signals for Lorentz violation in electrodynamics". Physical Review D. 66 (5): 056005. arXiv:hep-ph/0205211. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..66e6005K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.66.056005. S2CID 21309077.

- Hohensee; et al. (2010). "Improved constraints on isotropic shift and anisotropies of the speed of light using rotating cryogenic sapphire oscillators". Physical Review D. 82 (7): 076001. arXiv:1006.1376. Bibcode:2010PhRvD..82g6001H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.82.076001. S2CID 2612817.

- Hohensee; et al. (2010). "Covariant Quantization of Lorentz-Violating Electromagnetism". arXiv:1210.2683. Bibcode:2012arXiv1210.2683H. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Standalone version of work included in the Ph.D. Thesis of M.A. Hohensee. - Tobar; et al. (2005). "New methods of testing Lorentz violation in electrodynamics". Physical Review D. 71 (2): 025004. arXiv:hep-ph/0408006. Bibcode:2005PhRvD..71b5004T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.71.025004.

- Edwards, W. F. (1963). "Special Relativity in Anisotropic Space". American Journal of Physics. 31 (7): 482–489. Bibcode:1963AmJPh..31..482E. doi:10.1119/1.1969607.

- Zhang (1997), pp. 75–101

Further reading

- Janis, Allen (2010). "Conventionality of Simultaneity". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Mathpages: Conventional Wisdom, Round Trips and One-Way Speeds, Teaching Special Relativity

- Rizzi, Guido; Ruggiero, Matteo Luca; Serafini, Alessio (2005). "Synchronization Gauges and the Principles of Special Relativity". Foundations of Physics. 34 (12): 1835–1887. arXiv:gr-qc/0409105. Bibcode:2004FoPh...34.1835R. doi:10.1007/s10701-004-1624-3. S2CID 9772999.

- Sonego, Sebastiano; Pin, Massimo (2009). "Foundations of anisotropic relativistic mechanics". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 50 (4): 042902-1–042902-28. arXiv:0812.1294. Bibcode:2009JMP....50d2902S. doi:10.1063/1.3104065. S2CID 8701336.