Pachyophis

Pachyophis is an extinct genus of Simoliophiidae snakes that were extant during the Late Cretaceous period. More specifically, it was found to be from the Cenomanian Age about 93.9-100.5 million years ago in the suburb area of Bileca, Herzegovina.[2]

| Pachyophis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil specimen of Pachyophis woodwardi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | †Simoliophiidae |

| Genus: | †Pachyophis Nopsca, 1923[1] |

| Type species | |

| Pachyophis woodwardi Nopsca, 1923[1] | |

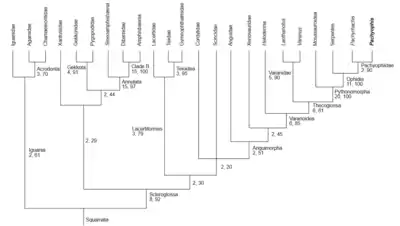

Pachyophis belongs to the family Simoliophiidae (hind-limbed snakes) in the clade Ophidia.[3] The family is characterized by the presence of hindlimbs and pelvic girdles, as seen in Pachyrhachis (one of the first discovered hind-limbed snakes). Included in the most basal of snake relatives, Pachyophis in contrast does not have evidence of any form of limb preservation. Despite this, they are considered under Pachyophiidae due to their other morphological similarities along with the generas Mesophis and Simoliophis.[4][5][3]

Only one species has been discovered for the genus Pachyophis. This holotype is known as Pachyophis woodwardi.[1]

Description

Pachyophis is considered a hind-limbed snake despite presence of any indication of forelimbs or shoulder girdle due to its other shared general morphology. All Simoliophiidae display evident pachyostosis (increase in bone massiveness) and osteosclerosis (increase in inner bone compactness). Pachyophis evidently displays such in their vertebrae specifically. Other shared characteristics include a smaller head and distally straight ribs for a lateral compression of the trunk.[6]

The holotype Pachyophis woodwardi exhibits a body extension of a total of 60 cm. The body structure of such has an overall flattened morphology and distinctively severe pachyostosis. This is especially in comparison to other related taxa like Pachyrhacis. The differences are likely attributed to adaptations to its aquatic dwelling habitat. All physical characteristic known are based solely specific on the three specimens discovered under this holotype.[7]

Skull

The skull itself is slender and pointed in nature. Relation wise, the skull is about an eighteenth of the trunk length. The jaw bones are more reminiscent of lizards than snakes. The upper jaw closely relates to that of varanids, scincoids, and dolichosaurids. The maxilla specifically resembles that of lepidosaurs more so than that of snakes. The lower jaw is more resembles that of dolichosaurids.[1][5]

The upper jaw measures 17 mm in length. Its shaped into a long triangular surface which is longitudinally concave and narrow in structure. Its highest point reaches 2.1mm forming a blunt tip and concave posterior outline on the shorter edge. The jawbone is approximately 1m thick. The anterior end represents the antorbital part of the jaw. A notable posterior concave outline represents the orbital opening as well as the beginning of the lacrimal. This projection then forms the connection of the jawbone with the palatine. At the anterior tip a small grove at the lower edge shows swollen character. Directly above it are two small groves with blunt lumps dividing them. This is representative of a suture and likely the location where the upper jawbone joins the premaxilla in the nasal opening region.[1]

The lower jaw measures 15.5mm in length and 1.9mm in width. The edges are elevated to produce a concavity that extends 3.5mm to a point posteriorly. The angular is the largest bone being widest anteriorly. It meets the splenial anteroventrally in a vertical joint. The splenial is preserved only at the joint, forming a bulge on the ventral margin. It is inferred then that the intramandibular joint is situated far anteriorly. This resembles that of Pachyrhachis. The tooth row extends the same length as exhibited in the upper jaw for equal alignment.[3]

Dentition

In contrast to the jaw, Pachyophis teeth clearly resemble that of snakes. Their dentition show thecodont nature, their teeth fitted into bowl like alveoli lined on the jaw bones. The enamel layer of the teeth is well developed with large, hollow pulp cavities possessing small openings leading into them. The tooth row extends the entirety of the jaw with the teeth curving backwards anteriorly. The first three teeth stand 2.8mm apart, with the following becoming more crowded so the last six teeth stand only 2.4mm apart. The more spaced teeth are longer and stronger in form, with lengths up to 1.6mm and 0.5mm thickness. The closer proximal teeth in contrast are shorter with lengths of 0.8mm and widths of 0.3mm.[1]

Vertebrae

The articulation of all the vertebrae together is very snakelike. Yet the construction of the vertebrae themselves are very unlike such.

The anterior vertebrae are smaller than the more posterior. The neural arches grow to be more swollen moving anterior to posterior, indicative of pachystotic nature. Zygosphenes presence are notable in some vertebrae. They project anteriorly from the neural arch and reach more dorsally than that of the zygapophyses located above the centrum. Neural spines rise from the zygosphene horizontally for a reach midlength of the vertebrae. This length increases to peak at the posterior end. At the anterior end, the neural arches are characteristically thin and shorter rising at an angle of 45o post dorsally. Prezygapophyses are inclined at 40 degree angle anteriorly, becoming almost horizontal in the middle and then reobtaining their inclination anteriorly. Postzygapophyses width is slightly larger than that of the prezygapophyses. Both do not project very far laterally, with the anterior being more elongated that the posterior.[7]

Ribs

The ribs are characterized by their needle like shape. Generally associated with the vertebrae, the ribs are technically not articulated to them. The upper third along the vertebral column are straight in shape, followed by a section of distinctive 120 degree bending, and then a return to the original straight form. The length of the ribs increases through the vertebral column. Pchyostosis also results in rib thickening, where the proximal section in each rib is around three times thicker in the posterior most than the anterior most. All exhibit a tapering to the distal tip for a consistent slender end.[7]

Scales

Exact knowledge of scalation of Pachyophis is not definitive. Scale repetition is defined in transverse rows, running parallel to one at notable right angles to the cervical vertebral column. Each bulge believed to be a scale is approximately 2.2mm in length, with minimal thickness and spacing between neighbors of about 0.8mm.[1]

Paleobiology

Habitat

Pachyophis likely dwelled in shallow aquatic sea regions as evidenced by fossil location and morphology. Pre and post zygapophyses lend to undulating horizontal movement of the body. The neck in addition to this, had more flexibility and also indicates a range of vertical movement. This likely means that the Pachyophis' would hold its head above its flat bodied stature, indicative of shallow water dwelling character.[8]

Fossils were preserved specifically in calcareous mud, indicative of very little water movement in the environment. The rocks of Selišta were deposited in environments analogous to patch reef and inter reef basin systems. It is likely that Pachyophis coexisted along a diverse assemblage of marine squamates with a large diversity of fish fauna of a limited wave action lagoons.[8][9]

Diet

Pachyophis' narrowly tapered mouth and sharp backward pointing teeth indicates its carnivorous diet by action of gripping versus biting methods. The jaw-teeth structure is designed for simultaneous grabbing and swallowing, fighting back against the forward pushing force of escaping prey. The jaw's posterior elongation was also notably blocked from opening very wide, another usual characteristic of snake feeding mechanisms. Thus soft, small and slippery animals were likely the main form of prey. Specifically, marine worms.[1]

Discovery

There is a single species discovered of Pachyophis, found in 1923 by F. Nopsca. The holotype Pachyophis woodwardi was discovered in a quarry in an eastern suburb of Bileca known as Selišta, located in East Herzegovina 40 km inland from Dubrovnik. Fossils of the area are generally from the Cenomanian-Turonian age, with Pachyophis being slightly younger found ranging in the mid to late Cenomanian layers.[1]

Three known preserved fossil specimens have been found. Specimens were preserved in bedded carbonate mudstone. One specimen was a postcranial skeleton and disarticulated skull preserved on a large slab of stone. Adjacently was another slab preserving three vertebral column segments in cross section. It is not known if these were all from the same individual organism. Yet the consistent ventral view, related bone size, and the overall skeletal arrangement does suggest such.[7]

- The only identifiable pieces of the skull in the larger slab was determined to be a well preserved maxilla and the posterior portion of the lower jaw.[7]

- The first of the vertebral segments consisted of thirty three articulated vertebrae with ribs. Following this was nine vertebrae shown in dorsal view, with the last few shown in right lateral face. Pelvic girdle and hindlimbs are absent. This segment is thought to represent the cervical vertebrae and few following dorsal.[7]

- The second segment is smaller and in ventral view consisting of sixteen articulated dorsal vertebrae with ribs. Less structural information is drawn from this segment, though all do display characteristic pachyostosis and osteosclerosis. Thickening proximal rib sections and notable emphasis anteriorly specifically. This segment is thought to represent the posterior dorsal section.[7]

- The third segment is most evident of pachyostotic ribs, which appear articulated with the vertebral column.[7]

See also

References

- Nopsca, F. (1923). "Eidolosaurus und Pachyophis, Zwei neue Neocom-Reptilien". Palaeontographica (55): 97–154.

- Rage, Jean-Claude; Escuillie, Francois (2003). "The Cenomanian: stage of hindlimbed snakes". Carnets de Géologie. CG2003 (A01–en): 1–11.

- Lee, Michael; Caldwell, Michael; Scanlon, John (1999). "A second primitive marine snake: Pachyophis woodwardi from the Cretaceous of Bosnia-Herzegovina". Journal of Zoology. 248 (4): 509–520. doi:10.1017/s0952836999008109.

- Rage, Jean-Claude (2003). "The Cenomanian: Stage of Hindlimbed Snakes" (PDF). Carnets de Géologie. CG2003 (A01–en): 1–11. doi:10.4267/2042/293.

- Bardet, Nathalie (2008). "The Cenomanian-Turonian (late Cretaceous) radiation of marine squamates (Reptilia): the role of the Mediterranean Tethys". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 179 (6): 605–623. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.179.6.605.

- Lee, Michael; Scanlon, John (28 November 2002). "The Cretaceous marine squamate Mesoleptos and the origin of snakes". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum. 68 (2): 121–142. doi:10.1017/s0968047002000158.

- Houssaye, Alexandra. "Rediscovery and the description of the second specimen of the hind-limbed snake Pachyophis woodwardi Nopsca, 1923 (Squamata, Ophidia) from the Cenomanian of Bosnia Herzegovina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (1): 276–279. doi:10.1080/02724630903416043. S2CID 84947278.

- Caldwell, Michael; Albino, Adriana (2001). "Palaeoenvironment and palaeoecology of three Cretaceous snakes: Pachyophis, Pachyrhachis, and Dinilysia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 46 (2): 203–318.

- "Pachyophis woodwardi Nopsca 1923 (snake)". Fossilworks. Retrieved 27 February 2017.