Panthera spelaea

Panthera spelaea, also known as the "Eurasian cave lion", "European cave lion", or "steppe lion",[1] is an extinct Panthera species that evolved in Europe probably after the third Cromerian interglacial stage, less than 600,000 years ago. Phylogenetic analysis of fossil bone samples revealed that it was highly distinct and genetically isolated from the modern lion (Panthera leo) occurring in Africa and Asia.[2] Analysis of morphological differences and mitochondrial data support the taxonomic recognition of Panthera spelaea as a distinct species that diverged from the lion about 1.9 million years ago.[3][4] Nuclear genomic evidence suggests a more recent split approximately 500,000 years ago, with no subsequent interbreeding with the ancestors of the modern lion.[5] The oldest known bone fragments were excavated in Yakutia and radiocarbon dated at least 62,400 years old. It became extinct about 13,000 years ago.[6]

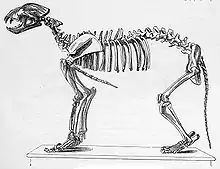

| Panthera spelaea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton in Natural History Museum, Vienna | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | †P. spelaea |

| Binomial name | |

| †Panthera spelaea Goldfuss, 1810 | |

| |

| Red indicates the maximal range of Panthera spelaea, blue Panthera atrox, and green Panthera leo. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

Felis spelaea was the scientific name used by the German paleontologist Georg August Goldfuss in 1810 for a fossil lion skull that was excavated in a cave in southern Germany.[7] It possibly dates to the Würm glaciation.[8][6][2]

Several authors regarded Panthera spelaea as a subspecies of the modern lion and therefore Panthera leo spelaea.[9][10][11][2] One author considered the cave lion to be more closely related to the tiger based on a comparison of skull shapes, and proposed the scientific name Panthera tigris spelaea.[12]

Results from morphological studies indicate that it is distinct in cranial and dental anatomy to justify specific status of Panthera spelaea.[13][14] Results of phylogenetic studies also support this assessment.[15][3][4]

In 2001, the subspecies P. spelaea vereshchagini was proposed for seven specimens found in Siberia and Yukon, which have smaller skulls and teeth than average member of P. spelaea.[16] Genetic analysis using ancient DNA provided no evidence for their distinct subspecific status; DNA signatures from P. spelaea from Europe and Alaska were indistinguishable, suggesting one large panmictic population.[3] Analysis of mitochondrial genome sequences from 31 cave lions showed that they fall into two monophyletic clades. One lived across western Europe and the other was restricted to Beringia during the Pleistocene.[17]

Evolution

BisonsPoursuivisParDesLions.jpg.webp)

Lion-like pantherine felids first appeared in the Tanzanian Olduvai Gorge about 1.7 to 1.2 million years ago. These cats dispersed to Europe from East Africa in the first half of the Middle Pleistocene, giving rise to P. fossilis in Central Europe by 610,000 years ago.[19] Panthera spelaea evolved from P. fossilis about 460,000 years ago in central Europe during the late Saalian glaciation or early Eemian and would have been common throughout Eurasia from 450,000 to 14,000 years ago. Recent nuclear genomic evidence suggest that interbreeding between modern lions and all Eurasian fossil lions took place up until 500,000 years ago, but by 470,000 years ago, no subsequent interbreeding between the two lineages occurred.[19][2][5]

P. spelaea bone fragments excavated in Poland were radiocarbon dated to between the early and late Weichselian glaciation, and are between 109,000 and 57,000 years old.[20] In Eurasia, it became extinct between 14,900 and 14,100 years ago, and survived in Beringia until 13,800 to 13,300 years ago as the Weichselian glaciation receded.[6][5] Mitochondrial DNA sequence data from fossil lion remains show that the American lion represents a sister group of P. spelaea, and likely arose when an early P. spelaea population became isolated south of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet about 340,000 years ago.[3] The following cladogram shows the genetic relationship between P. spelaea and other pantherine cats.[4]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Characteristics

Carvings and cave paintings of lions discovered in the Lascaux and Chauvet Caves in France were dated to 15,000 to 17,000 years old.[21][18] A drawing in the Chauvet cave depicts two cave lions walking together. The one in the foreground is slightly smaller than the one in the background, which has been drawn with a scrotum and without a mane.[22] Such cave paintings suggest that male cave lions completely lacked manes, or at most had very small manes.[6] P. spelaea is also known from the Löwenmensch figurine found in Vogelherd cave in the Swabian Alb, southwest Germany, which dates to the Aurignacian culture. These archaeological artifacts indicate that it may have been featured in Paleolithic religious rituals.[23][24]

P. spelaea was thought to have been one of the largest lion species. The skeleton of an adult male found in 1985 near Siegsdorf in Germany had a shoulder height of around 1.2 m (3.9 ft) and a head-body length of 2.1 m (6.9 ft) without the tail, similar in size to large modern lions. The size of this male was exceeded by other specimens, with another male reaching 2.5 m (8.2 ft) long without the tail. Similarly, footprints attributed to a male cave lion measured 15 cm (5.9 in) across. The heaviest Panthera spelaea was estimated to weigh 339 kg (747 lb).[25] This shows that P. spelaea would have been up to or over 12% larger than modern lions, but still smaller than the earlier Panthera fossilis or the American lion (P. atrox). Cave paintings almost exclusively show hunting animals without a mane, suggesting that males were indeed maneless.[26][27] P. spelaea had a relatively longer and narrower muzzle compared to that of the extant lion. Despite this, the two species do not exhibit major differences in morphology.[6] Like modern lions, females were smaller than males.[28]

In 2016, hair found near the Maly Anyuy River was identified as cave lion hair through DNA analysis. Comparison with hair of a modern lion revealed that cave lion hair was probably similar in colour as that of the modern lion, though slightly lighter. In addition, the cave lion is thought to have had a very thick and dense undercoat comprising closed and compressed yellowish-to-white wavy downy hair with a smaller mass of darker-coloured guard hairs, possibly an adaptation to the Ice Age climate.[29]

Distribution and habitat

P. spelaea formed a contiguous population from Europe to Alaska over the Bering land bridge, across the range of the mammoth steppe.[30] It was widely distributed from the Iberian peninsula, Southeast Europe, Great Britain, Central Europe, the East European Plain, and across most of northern Eurasia into Canada and Alaska. The oldest known fossils were excavated in northeastern Yakutia and were radiocarbon dated at 62,400 years old. The youngest known fossils are dated 11,925 years old and originated near Fairbanks, Alaska.[6] Phalanx bones excavated in Spain's La Garma cave complex were radiocarbon dated to 14,300–14,000 years old.[31] In Slovakia, skull, femur and pelvis remains were excavated in ten Karst caves in hilly and montane areas at elevations from 240 to 1,133 m (787 to 3,717 ft).[32] In Yakutia's Khayrgas Cave, bones of P. spelaea were found together with remains of humans, wolf, reindeer, Pleistocene horse and fish in a layer dated 13,200–21,500 years old.[33] In 2008, a well-preserved mature cave lion specimen was unearthed near the Maly Anyuy River in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug in Russia, which still retained some clumps of hair.[34] The cave lion was probably predominantly found in open habitits such as steppe and grasslands although it would have also have occurred in open woodlands as well.[6]

Discoveries

In 2015, two frozen cave lion cubs, estimated to be between 25,000 and 55,000 years old, were discovered close to the Uyandina River in Yakutia, Siberia in permafrost.[35][36][37] Research results indicate that the cubs were likely barely a week old at the time of their deaths, as their milk teeth had not fully erupted. Further evidence suggests the cubs were hidden at a den site until they were strong enough to follow their mother back to the pride, as with modern lions. Researchers believe that the cubs were trapped and killed by a landslide, and that the absence of oxygen underground hindered their decomposition and allowed the cubs to be preserved in such good condition. A second expedition to the site where the cubs were found was planned for 2016, in hopes of finding either the remains of a third cub or possibly the cubs' mother.[38]

In 2017, another frozen specimen, thought to be a lion cub, was found in Yakutia on the banks of the Tirekhtyakh River (Russian: Тирехтях), a tributary of the Indigirka River. Named 'Boris',[39] this cat was believed to be slightly older than the 2015 cubs at the time of its death; it is estimated to have been around one and a half to two months.[40] In 2018, another preserved carcass of a cub was found in a location 15 m (49 ft) away. Named 'Spartak', it was considered to be around a month old when it died approximately 50,000 years ago, and presumed to be a sibling to Boris.[39]

Paleobiology

P. spelaea inhabited open environment such as mammoth steppe and boreal forest. It was one of the keystone species of the mammoth steppe, being one of the main apex predators alongside grey wolf, cave hyena and brown bear.[42] Large amounts of bones belonging to P. spelaea were excavated in caves, where bones of cave hyena, cave bear and Paleolithic artefacts were also found.[43][44] It is unclear whether P. spelaea was social like the modern lion; some evidence indicates that it may have been solitary.[42]

Isotopic analyses of bone collagen samples extracted from fossils indicate that cave bear cubs, reindeer and other cervids were prominent in the diet of cave lions. Later cave lions seem to have preyed foremost on reindeer, up to the brink of local extinction or extirpation of both species.[45] Other possible prey species were giant deer, red deer, wild horse, musk ox, aurochs, wisent, steppe bison, young woolly rhino and young woolly mammoth. It likely competed for prey with the European Ice Age leopard (P. pardus spelaea) as well as cave hyenas, cave bears and wolves.[46] An Isotope analysis study suggested most sampled P. spelea specimens were primarily consuming reindeer.[42]

See also

References

- Diedrich, C. G. (2014). "Palaeopopulations of Late Pleistocene Top Predators in Europe: Ice Age Spotted Hyenas and Steppe Lions in Battle and Competition about Prey". Paleontology Journal. 2014: 1–34. doi:10.1155/2014/106203.

- Burger, J.; Rosendahl, W.; Loreille, O.; Hemmer, H.; Eriksson, T.; Götherström, A.; Hiller, J.; Collins, M. J.; Wess, T.; Alt, K. W. (2004). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (3): 841–849. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.020. PMID 15012963.

- Barnett, R., Shapiro, B., Barnes, I. A. N., Ho, S. Y., Burger, J., Yamaguchi, N., Higham, T. F., Wheeler, H., Rosendahl, W., Sher, A. V., Sotnikova, M. (2009). "Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 18 (8): 1668–1677. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. PMID 19302360. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2012.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Barnett, R.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Soares, A. E. R.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Zazula, G.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Kirillova, I. V.; Larson, G.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2016). "Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), Resolve its Position within the Panthera Cats". Open Quaternary. 2: 4. doi:10.5334/oq.24.

- Manuel, M. d.; Ross, B.; Sandoval-Velasco, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Liu, S.; Martin, M. D.; Sinding, M.-H. S.; Mak, S. S. T.; Carøe, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Zheng, J.; Zazula, G.; Baryshnikov, G.; Eizirik, E.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Antunes, A.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Larson, G.; Yang, H.; O’Brien, S. J.; Hansen, A. J.; Zhang, G.; Marques-Bonet, T. & Gilbert, M. T. P. (2020). "The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (20): 10927–10934. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919423117. PMC 7245068. PMID 32366643.

- Stuart, A. J., Lister, A. M. (2011). "Extinction chronology of the cave lion Panthera spelaea". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17): 2329–2340. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.2329S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.023.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Goldfuss, G. A. (1810). Die Umgebungen von Muggensdorf. Erlangen: Johann Jakob Palm.

- Diedrich, C. G. (2008). "The holotypes of the upper Pleistocene Crocuta crocuta spelaea (Goldfuss, 1823: Hyaenidae) and Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810: Felidae) of the Zoolithen Cave hyena den (South Germany) and their palaeo-ecological interpretation". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 154 (4): 822–831. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00425.x.

- Kurtén, B. (1968). Pleistocene Mammals of Europe <publisher=Weidenfeld and Nicolson. London.

- Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung 17: 167–280.

- Turner, A. (1984). "Dental sex dimorphism in European lions (Panthera leo L.) of the Upper Pleistocene: palaeoecological and palaeoethological implications". Annales Zoologici Fennici. 21: 1–8.

- Groiss, J. Th. (1996). "Der Höhlentiger Panthera tigris spelaea (Goldfuss)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie (7): 399–414. doi:10.1127/njgpm/1996/1996/399.

- Spassov, N., Iliev, N. (1994). "Animal remains from the submerged Late Eneolithic – early Bronze Age settlements in Sozopol (South Bulgarian Black Sea Coast)". Proceedings of the International Symposium VI. Thracia Pontica. pp. 287–314.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sotnikova, M., Nikolskiy, P. (2006). "Systematic position of the cave lion Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss) based on cranial and dental characters". Quaternary International. 142–143: 218–228. Bibcode:2006QuInt.142..218S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2005.03.019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Christiansen, P. (2008). "Phylogeny of the great cats (Felidae: Pantherinae), and the influence of fossil taxa and missing characters". Cladistics. 24 (6): 977–992. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00226.x. S2CID 84497516.

- Baryshnikov, G. F.; Boeskorov, G. (2001). "The Pleistocene cave lion, Panthera spelaea (Carnivora, Felidae) from Yakutia, Russia". Cranium. 18 (1): 7–24.

- Stanton, D.W.; Alberti, F.; Plotnikov, V.; Androsov, S.; Grigoriev, S.; Fedorov, S.; Kosintsev, P.; Nagel, D.; Vartanyan, S.; Barnes, I. & Barnett, R. (2020). "Early Pleistocene origin and extensive intra-species diversity of the extinct cave lion". Scientific Reports. 10: 12621. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1012621S. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69474-1. PMID 32724178.

- Chauvet, J.-M.; Brunel, D. E.; Hillaire, C. (1996). Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave. The oldest known paintings in the world. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Sotnikova, M.V. & Foronova, I.V. (2014). "First Asian record of Panthera (Leo) fossilis (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae) in the Early Pleistocene of Western Siberia, Russia". Integrative Zoology. 9 (4): 517–530. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12082. PMID 24382145.

- Marciszak, A. & Stefaniak, K. (2010). "Two forms of cave lion: Middle Pleistocene Panthera spelaea fossilis Reichenau, 1906 and Upper Pleistocene Panthera spelaea spelaea Goldfuss, 1810 from the Bisnik Cave, Poland". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 258 (3): 339–351. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0117.

- Leroi-Gourhan, A.; Allain, J. (1979). Lascaux inconnu. XXIIe supplement à "Gallia Préhistoire". Paris.

- Yamaguchi, N.; Cooper, A.; Werdelin, L.; MacDonald, D. W. (2004). "Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review". Journal of Zoology. 263 (4): 329–342. doi:10.1017/S0952836904005242.

- Bahn, P. G.; Vertut, J. (1997). Journey Through the Ice Age. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Guthrie, R. D. (2005). The Nature of Paleolithic Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sherani, Shaheer (2016). "A new specimen-dependent method of estimating felid body mass". PeerJ Preprints: 16. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.2327v2.

- Koenigswald, W. v. (2002). Lebendige Eiszeit: Klima und Tierwelt im Wandel (in German). Stuttgart: Theiss. ISBN 978-3-8062-1734-6.

- Koenigswald, W. v. (2002). Lebendige Eiszeit. Darmstadt: Theiss-Wissenschaftliche Buchgemeinschaft. ISBN 3-8062-1734-3.

- Diedrich, C. G. (2011). "Late Pleistocene Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) skeletons from the Czech Republic (central Europe); their pathological cranial features and injuries resulting from intraspecific fights, conflicts with hyenas, and attacks on cave bears". Bulletin of Geosciences. 86 (4): 817–840. doi:10.3140/bull.geosci.1263.

- Chernova, O. F., Kirillova, I. V., Shapiro, B., Shidlovskiy, F. K., Soares, A. E. R., Levchenko, V. A., and Bertuch, F. (2016). "Morphological and genetic identification and isotopic study of the hair of a cave lion (Panthera spelaea Goldfuss, 1810) from the Malyi Anyui River (Chukotka, Russia)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 142: 61–73. Bibcode:2016QSRv..142...61C. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.04.018.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Ersmark, E., Orlando, L., Sandoval-Castellanos, E., Barnes, I., Barnett, R., Stuart, A., Lister, A., Dalén, L. (2015). "Population Demography and Genetic Diversity in the Pleistocene Cave Lion". Open Quaternary. 1 (1): Art. 4. doi:10.5334/oq.aa.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cueto, M., Camarós, E., Castaños, P., Ontañón, R., and Arias, P. (2016). "Under the Skin of a Lion: Unique Evidence of Upper Paleolithic Exploitation and Use of Cave Lion (Panthera spelaea) from the Lower Gallery of La Garma (Spain)". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0163591. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1163591C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163591. PMC 5082676. PMID 27783697.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sabol, M. (2011). "A record of Pleistocene lion-like felids in the territory of Slovakia". Quaternaire. Hors-série (4): 215−228.

- Kuzmin, Y. V., Kosintsev, P. A., Stepanov, A. D., Boeskorov, G. G., and Cruz, R. J. (2017). "Chronology and faunal remains of the Khayrgas Cave (Eastern Siberia, Russia)" (PDF). Radiocarbon. 59 (2): 575−582. doi:10.1017/RDC.2016.39. S2CID 133453976.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kirillova, I. V., Tiunov, A. V., Levchenko, V. A., Chernova, O. F., Yudin, V. G., Bertuch, F., and Shidlovskiy, F.,K. (2015). "On the discovery of a cave lion from the Malyi Anyui River (Chukotka, Russia)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 117: 135–151. Bibcode:2015QSRv..117..135K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.03.029.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Extinct lion cubs found in Siberia are up to 55,000 years old - latest test results reveal". The Siberian Times. 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "Meet this extinct cave lion, at least 10,000 years old - world exclusive". siberiantimes.com. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Switek, B. (2015). "Frozen Cave Lion Cubs from the Ice Age Found in Siberia". National Geographic News. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- "Whiskers still bristling after more than 12,000 years in the Siberian cold". The Siberian Times. 17 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Gertcyk, Olga (12 September 2018). "Cute first pictures of new 50,000 year old cave lion cub found perfectly preserved in permafrost". The Siberian Times. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Extinct cave lion cub in 'perfect' condition found in Siberia rising cloning hopes". The Siberian Times. 9 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Bölsche, W. & Harder, H. (1900). Tiere der Urwelt. Serie III. Wandsbek-Hamburg: Verlag der Kakao-Compagnie Theodor Reichardt.

- Bocherens, H. (2015). "Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe". Quaternary Science Reviews. 117: 42–71. Bibcode:2015QSRv..117...42B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.03.018.

- Diedrich, C. G. (2011). "The largest European lion Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss 1810) population from the Zoolithen Cave, Germany: specialised cave bear predators of Europe". Historical Biology. 23 (2–3): 271–311. doi:10.1080/08912963.2010.546529. S2CID 86638786.

- Diedrich, C. G. (2011). "Pleistocene Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss 1810) remains from the Balve cave (NW Germany) - a cave bear, hyena den and middle palaeolithic human cave – and review of the Sauerland Karst lion cave sites". Quaternaire. 22 (2): 105–127. doi:10.4000/quaternaire.5897.

- Bocherens, H.; Drucker, D. G.; Bonjean, D.; Bridault, A.; Conard, N. J.; Cupillard, C.; Germonpré, M.; Höneisen, M.; Münzel, S. C.; Napierala, H. & Patou-Mathis, M. (2011). "Isotopic evidence for dietary ecology of cave lion (Panthera spelaea) in North-Western Europe: prey choice, competition and implications for extinction" (PDF). Quaternary International. 245 (2): 249–261. Bibcode:2011QuInt.245..249B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.02.023.

- Diedrich, C. G. (2013). "Late Pleistocene leopards across Europe – northernmost European German population, highest elevated records in the Swiss Alps, complete skeletons in the Bosnia Herzegowina Dinarids and comparison to the Ice Age cave art". Quaternary Science Reviews. 76: 167–193. Bibcode:2013QSRv...76..167D. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.05.009.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Panthera spelaea. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera spelaea. |

- Prehistoric cats and prehistoric cat-like creatures, from the Messybeast Cat Resource Archive

- The mammoth and the flood, volume 5, chapter 1, by Hans Krause.

- Hoyle and cavetigers, from the Dinosaur Mailing List. (Groiss)