Park Yong-man

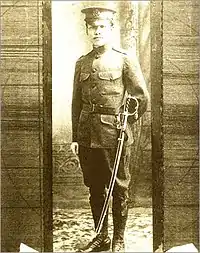

Park Yong-man (Korean: 박용만); (2 July 1881 – 17 October 1928) was a Korean nationalist and independence activist who, after spending time in prison for reformist activities, immigrated to the United States of America. There Park was involved in the establishment of various Korean nationalist organizations in Denver, Nebraska and Hawaii. Park also founded the Korean Military Corps. Following the March 1st movement in 1919, Park became involved with the military training of Korean nationalists in China, but may have also engaged in anti-communist activity. Park was assassinated in Beijing by a Korean communist.

Park Yong-man | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 July 1881 |

| Died | 17 October 1928 (aged 47) |

| Nationality | Korean |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Pak Yong-man |

| McCune–Reischauer | Pak Yongman |

Early life

Park was born on 2 July 1881 in Cheorwon, a rural town in Gangwon province to a family with military traditions. After the death of his parents in his early childhood, Park was raised by his uncle, Park Hee-Byung. Together with his uncle, Park moved to Seoul, and then to Japan. He developed reformist leanings while in Japan, and upon his return to Korea, around 1897, became involved with various reformist and protest movements. His activities were frowned upon by the government and Park was imprisoned.[1]

It was while he was incarcerated that he met Syngman Rhee, another reformist. Rhee was working on a book, "The Spirit of Independence", a treatise on reform and patriotism. Park assisted Rhee in the writing of his book, and smuggled the manuscript out of prison upon his release around 1903.[2] His uncle had by now returned to Korea and Park joined him in Sonchon, in what is now North Korea, and worked at a private school.[1] In late 1904 or early 1905, Park emigrated to the United States of America.[3][4]

Emigration to the U.S.

Life in Nebraska

Initially settling in Nebraska, Park was a student at the Hastings College. He then moved to Denver, Colorado to again join his uncle, who had also moved to the United States and was one of the first Korean immigrants to live in Denver. Together with his uncle, Park helped organise a Korean nationalist network in Denver. However, when his uncle was assassinated in 1907,[5] Park subsequently returned to Nebraska, this time to Lincoln to study political and military science at the University of Nebraska.[3]

By June 1909, and now recognized as one of the leaders of the Korean-American community, Park established a military school in Kearney, Nebraska.[6] Park was a firm believer in military action against Japan in order to achieve an independent Korea, and such action clearly required trained fighters.[2] With his school, he aimed to provide young Korean-Americans with military drills and training for the anticipated clash with Japan. History, English, Korean and even agriculture were also taught to students.[7]

By 1910, Park was dabbling in journalism and was editor of the Korean newspaper The New Korea (신한민보) published by the recently established Korean National Association (KNA) in San Francisco.[1] Syngman Rhee, by now released from prison and living in the United States, was asked to take over Park's military school, which had shifted from Kearney to Hastings, Nebraska. Upon his arrival, Rhee was highly critical of the school and only stayed a short time before departing.[7] The school eventually was closed in 1915.[1]

Life in Hawaii

The KNA had one of its two headquarters in Hawaii, the other being in San Francisco,[2] and Park served as its vice-chairman for a time.[8] This necessitated a move to Honolulu in 1912, and he continued his editorial work at the Korean National Herald.

Also while in Hawaii, as Park still considered that a military confrontation with Japan was likely, he established the Korean Military Corps. A firm believer in the use of military force to secure independence for Korea, Park gradually fell out with Syngman Rhee and others in the KNA, who favored a more diplomatic solution to Korea's annexation by Japan. There were also clashes over funding, with Rhee preferring the available funds collected from the Korean-American community to be spent on education rather than maintaining the Korean Military Corps.[4] The funding issue became problematic, and the Corps was shut down in 1917 because of this.[8]

Back in Korea, opposition to Japanese rule was increasing, and following the 1 March 1919 uprising which resulted in the Declaration of Independence, Park translated the Declaration into English for publication in Honolulu.[3] Then, in May 1919, Park joined the American Expeditionary Force, which was embarking for Siberia.[1]

Return to Asia

The American Expeditionary Force had been dispatched to Siberia in 1918 to assist the Czechoslovak Legions in their retreat from the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War. Japanese forces were also present in the region, nominally to assist in fighting the Bolsheviks, but also as part of a process to expand their influence in North East Asia. Consequently, Park appears to have considered his sojourn to Siberia as an ideal start to combating Japanese colonialism.[1] His role with the American Expeditionary Force was as an intelligence officer, and it is likely that he collected information on the communist Koreans present in Siberia at the time.[3]

In the interim, three separate Provisional Governments of Korea (PGK) had been established, one each in Seoul, Vladivistok and Shanghai. By September 1919, these had merged into a single government in Shanghai, with Syngman Rhee (in absentia) appointed as president. Park was offered the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Government.[9] Park, having finished his duties with the American Expeditionary Force, arrived in Shanghai in March 1920. However, it seems that Park was only part of the PGK for a few months, if at all.[6] It is possible that the selection of Syngman Rhee as head of the PKG was a factor in deterring Park from playing a more significant role with the organisation.[1]

Park was also involved with negotiations to form a secret mutual defense pact between the newly established PGK and the Soviets. Park was now based in Manchuria, spending time training recruits and preparing for a military campaign against Japan. Little is known about his activities in Manchuria, but he returned to Korea at least once, in 1924, with a group of military and business leaders of the pro-Japanese Chinese government.[3] Park, now under suspicion of collaborating with the Japanese against communism due to his activities in Siberia and Manchuria, was assassinated in Beijing on 17 October 1928 by a Korean communist, Lee Hae-young.[8]

Notes

- Kim, 2002, pp. 16-17

- Choe, Kim & Han, 2003

- Kim, 2003

- Tikhonov, 2009

- McGhee, 2007

- Lee, 1963 pp. 318

- Nielsen, 1997

- Choi, 2002 pp. 43-71

- Neff, 2010

References

- Yong-Ho Choe; Ilpyong J. Kim; Moo-Young Han (2003). "Annotated Chronology of the Korean Immigration to the United States, 1882 to 1952". www.duke.edu. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Choi Zihn (2002). "Early Korean Immigrants to America: their Role in the Establishment of the Republic of Korea". East Asia Review. 14 (4): 43–71.

- Han-Kyo Kim (Spring–Summer 2002). "The Korean Independence Movement in the United States: Syngman Rhee, An Chang-Ho, and Pak Yong-Man". International Journal of Korean Studies: 16–17.

- Young-Sik Kim (11 September 2003). "The Korean Americans in the War of Independence". www.asianresearch.org. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Chong-Sik Lee (1963). The Politics of Korean Nationalism. The Center for Japanese Studies.

- Tom McGhee (14 October 2007). "Korean-Americans honor their roots". Denver Post. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Robert Neff (28 March 2010). "Provisional Government in Shanghai Resisted Colonial Rule". www.koreatimes.co.kr. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Margaret Stines Nielsen (May–June 1997). "The Korean Connection". Buffalo Tales. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Vladimir Tikhonov (16 March 2009). "Militarism and Anti-militarism in South Korea: ""Militarized Masculinity" and the Conscientious Objector Movement"". www.japanfocus.org. Retrieved 15 July 2011.