Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's [9] is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly and, as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms become more common.[1][4] The most obvious early symptoms are tremor, rigidity, slowness of movement, and difficulty with walking.[1] Cognitive and behavioral problems may also occur with depression, anxiety, and apathy occurring in many people with PD.[10] Parkinson's disease dementia becomes common in the advanced stages of the disease. Those with Parkinson's can also have problems with their sleep and sensory systems.[1][2] The motor symptoms of the disease result from the death of cells in the substantia nigra, a region of the midbrain, leading to a dopamine deficit.[1] The cause of this cell death is poorly understood, but involves the build-up of misfolded proteins into Lewy bodies in the neurons.[11][4] Collectively, the main motor symptoms are also known as "parkinsonism" or a "parkinsonian syndrome".[4]

| Parkinson's disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Parkinson disease, idiopathic or primary parkinsonism, hypokinetic rigid syndrome, paralysis agitans, shaking palsy |

.png.webp) | |

| Illustration of Parkinson's disease by William Richard Gowers, first published in A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System (1886) | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | tremor, rigidity, slowness of movement, difficulty walking[1] |

| Complications | Dementia, depression, anxiety[2] |

| Usual onset | Age over 60[1][3] |

| Causes | Unknown[4] |

| Risk factors | Pesticide exposure, head injuries[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Dementia with Lewy bodies, progressive supranuclear palsy, essential tremor, antipsychotic use[5] |

| Treatment | Medications, surgery[1] |

| Medication | L-DOPA, dopamine agonists[2] |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy about 7–15 years [6] |

| Frequency | 6.2 million (2015)[7] |

| Deaths | 117,400 (2015)[8] |

The cause of PD is unknown, with both inherited and environmental factors being believed to play a role.[4] Those with a family member affected by PD are at an increased risk of getting the disease, with certain genes known to be inheritable risk factors.[12] Other risk factors are those who have been exposed to certain pesticides and who have prior head injuries. Tobacco smokers and coffee and tea drinkers are at a reduced risk.[4][13]

Diagnosis of typical cases is mainly based on symptoms, with motor symptoms being the chief complaint. Tests such as neuroimaging (MRI or imaging to look at dopamine neuronal dysfunction known as DaT scan) can be used to help rule out other diseases.[14][1] Parkinson's disease typically occurs in people over the age of 60, of whom about one percent are affected.[1][3] Males are more often affected than females at a ratio of around 3:2.[4] When it is seen in people before the age of 50, it is called early-onset PD.[15] In 2015, PD affected 6.2 million people and resulted in about 117,400 deaths globally.[7][8] The average life expectancy following diagnosis is between 7 and 15 years.[2]

There is no cure for PD; treatment aims to improve the symptoms.[1][16] Initial treatment is typically with the medications levodopa (L-DOPA), MAO-B inhibitors, or dopamine agonists.[14] As the disease progresses, these medications become less effective, while at the same time producing a side effect marked by involuntary muscle movements.[2] At that time, medications may be used in combination and doses may be increased.[14] Diet and certain forms of rehabilitation have shown some effectiveness at improving symptoms.[17][18] Surgery to place microelectrodes for deep brain stimulation has been used to reduce motor symptoms in severe cases where drugs are ineffective.[1] Evidence for treatments for the non-movement-related symptoms of PD, such as sleep disturbances and emotional problems, is less strong.[4]

The disease is named after the English doctor James Parkinson, who published the first detailed description in An Essay on the Shaking Palsy, in 1817.[19][20] Public awareness campaigns include World Parkinson's Day (on the birthday of James Parkinson, 11 April) and the use of a red tulip as the symbol of the disease.[21] People with Parkinson's who have increased the public's awareness of the condition include the boxer Muhammad Ali, actor Michael J. Fox, Olympic cyclist Davis Phinney, and actor Alan Alda.[22][23][24][25]

Classification

Parkinson's disease is the most common form of parkinsonism and is sometimes called "idiopathic parkinsonism", meaning parkinsonism with no identifiable cause.[16][26] Scientists sometimes refer to Parkinson’s disease as a type of neurodegenerative disease called synucleinopathy due to an abnormal accumulation of the protein alpha-synuclein in the brain.[27] The synucleinopathy classification distinguishes Parkinson's disease from other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, where the brain accumulates a different protein known as the tau protein.[27]

Considerable clinical and pathological overlap exists between tauopathies and synucleinopathies, however there are also differences. In contrast to Parkinson's disease, people with Alzheimer's disease most commonly experience memory loss. The cardinal signs of Parkinson's disease (slowness, tremor, stiffness, and postural instability) are not normal features of Alzheimer's.

Attempts to classify Parkinson's disease into different subtypes have been made, with focus put on age of onset, progression of symptoms, and dominance of tremor. None have currently been widely adopted as a complete model.[28]

Signs and symptoms

The most recognizable symptoms in Parkinson's disease are movement ("motor") related.[31] Non-motor symptoms, which include autonomic dysfunction, neuropsychiatric problems (mood, cognition, behavior or thought alterations), and sensory (especially altered sense of smell) and sleep difficulties, are also common. Some of these non-motor symptoms may be present at the time of diagnosis.[31]

Motor

Four motor symptoms are considered cardinal in PD: tremor, slowness of movement (bradykinesia), rigidity, and postural instability.[31]

The most common presenting sign is a coarse slow tremor of the hand at rest which disappears during voluntary movement of the affected arm and in the deeper stages of sleep.[31] It typically appears in only one hand, eventually affecting both hands as the disease progresses.[31] Frequency of PD tremor is between 4 and 6 hertz (cycles per second). A feature of tremor is pill-rolling, the tendency of the index finger and thumb to touch and perform together a circular movement.[31][32] The term derives from the similarity between the movement of people with PD and the early pharmaceutical technique of manually making pills.[32]

Bradykinesia (slowness of movement) is found in every case of PD, and is due to disturbances in motor planning of movement initiation, and associated with difficulties along the whole course of the movement process, from planning to initiation to execution of a movement. Performance of sequential and simultaneous movement is impaired. Bradykinesia is the most handicapping symptom of Parkinson’s disease leading to difficulties with everyday tasks such as dressing, feeding, and bathing. It leads to particular difficulty in carrying out two independent motor activities at the same time and can be made worse by emotional stress or concurrent illnesses. Paradoxically people with Parkinson's disease can often ride a bicycle or climb stairs more easily than walk on a level. While most physicians may readily notice bradykinesia, formal assessment requires a person to do repetitive movements with their fingers and feet.[33]

Rigidity is stiffness and resistance to limb movement caused by increased muscle tone, an excessive and continuous contraction of muscles.[31] In parkinsonism, the rigidity can be uniform, known as "lead-pipe rigidity," or ratchety, known as "cogwheel rigidity."[16][31][34][35] The combination of tremor and increased tone is considered to be at the origin of cogwheel rigidity.[36] Rigidity may be associated with joint pain; such pain being a frequent initial manifestation of the disease.[31] In early stages of Parkinson's disease, rigidity is often asymmetrical and it tends to affect the neck and shoulder muscles prior to the muscles of the face and extremities.[37] With the progression of the disease, rigidity typically affects the whole body and reduces the ability to move.

Postural instability is typical in the later stages of the disease, leading to impaired balance and frequent falls,[38] and secondarily to bone fractures, loss of confidence, and reduced mobility.[39] Instability is often absent in the initial stages, especially in younger people, especially prior to the development of bilateral symptoms.[40] Up to 40% of people diagnosed with PD may experience falls and around 10% may have falls weekly, with the number of falls being related to the severity of PD.[31]

Other recognized motor signs and symptoms include gait and posture disturbances such as festination (rapid shuffling steps and a forward-flexed posture when walking with no flexed arm swing). Freezing of gait (brief arrests when the feet seem to get stuck to the floor, especially on turning or changing direction), a slurred monotonous quiet voice, mask-like facial expression, and handwriting that gets smaller and smaller are other common signs.[41]

Neuropsychiatric

Parkinson's disease can cause neuropsychiatric disturbances, which can range from mild to severe. This includes disorders of cognition, mood, behavior, and thought.[31]

Cognitive disturbances can occur in the early stages of the disease and sometimes prior to diagnosis, and increase in prevalence with duration of the disease.[31][42] The most common cognitive deficit in PD is executive dysfunction, which can include problems with planning, cognitive flexibility, abstract thinking, rule acquisition, inhibiting inappropriate actions, initiating appropriate actions, working memory, and control of attention.[42][43] Other cognitive difficulties include slowed cognitive processing speed, impaired recall and impaired perception and estimation of time.[42][43] Nevertheless, improvement appears when recall is aided by cues.[42] Visuospatial difficulties are also part of the disease, seen for example when the individual is asked to perform tests of facial recognition and perception of the orientation of drawn lines.[42][43]

A person with PD has two to six times the risk of dementia compared to the general population.[31][42] Up to 78% of people with PD have Parkinson's disease dementia.[44] The prevalence of dementia increases with age and, to a lesser degree, duration of the disease.[45] Dementia is associated with a reduced quality of life in people with PD and their caregivers, increased mortality, and a higher probability of needing nursing home care.[42]

Impulse control disorders including pathological gambling, compulsive sexual behavior, binge eating, compulsive shopping and reckless generosity can be caused by medication, particularly orally active dopamine agonists. The dopamine dysregulation syndrome – with wanting of medication leading to overusage – is a rare complication of levodopa use.[46]

Punding in which complicated repetitive aimless stereotyped behaviors occur for many hours is another disturbance caused by anti-Parkinson medication.

Psychosis

Psychosis can be considered a symptom with a prevalence at its widest range from 26 to 83%.[10][47] Hallucinations or delusions occur in approximately 50% of people with PD over the course of the illness, and may herald the emergence of dementia. These range from minor hallucinations – "sense of passage" (something quickly passing beside the person) or "sense of presence" (the perception of something/someone standing just to the side or behind the person) – to full blown vivid, formed visual hallucinations and paranoid ideation. Auditory hallucinations are uncommon in PD, and are rarely described as voices. It is now believed that psychosis is an integral part of the disease. A psychosis with delusions and associated delirium is a recognized complication of anti-Parkinson drug treatment and may also be caused by urinary tract infections (as frequently occurs in the fragile elderly), but drugs and infection are not the only factors, and underlying brain pathology or changes in neurotransmitters or their receptors (e.g., acetylcholine, serotonin) are also thought to play a role in psychosis in PD.[48][49]

Behavior and mood

Behavior and mood alterations are more common in PD without cognitive impairment than in the general population, and are usually present in PD with dementia. The most frequent mood difficulties are depression, apathy, and anxiety.[31]

Depression has been estimated to appear in anywhere from 20 to 35% of people with PD, and can appear at any stage of the disease. In Parkinson's, depression can manifest with symptoms that are common to the disease process (fatigue, insomnia, and difficulty with concentration) which makes diagnosis difficult. The imbalance and change in dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenergic hormones are known to be a primary cause of depression in PD affected people.[10] Another cause is the functional impairment that is caused by the disease.[50] Symptoms of depression can include loss of interest, sadness, guilt, feelings of helplessness/hopelessness/guilt, and suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation in PD affected people is higher than in the general population, but suicidal attempts themselves are lower than in people with depression without PD.[10][50] Risk factors for depression in PD can include disease onset under age 50, being a woman, previous history of depression, severe motor symptoms, and others.[10]

Anxiety has been estimated to have a prevalence in PD affected people around 30%-40% (however up to 60% has been found).[10][50] Anxiety can often be found during "off" periods (periods of time where medication is not working as well as it did before) with PD affected people suffering from panic attacks more frequently compared to the general population. Both anxiety and depression have been found to be associated with decreased quality of life.[10][51] Symptoms can range from mild and episodic to chronic with potential causes being abnormal gamma-aminobutyric acid levels as well as embarrassment or fear about their symptoms/disease.[10][51] Risk factors for anxiety in PD are disease onset under age 50, women, and "off" periods.[10]

Apathy and anhedonia can be defined as a loss of motivation and an impaired ability to experience pleasure, respectively. They are symptoms classically associated with depression however differ in PD affected people in treatment, mechanism, and doesn't always occur with depression. Apathy presents in around 16.5-40%. Symptoms of apathy include reduced initiative/interests in new activities or the world around them, emotional indifference, and loss of affection or concern for others.[10] Apathy is associated with deficits in cognitive functions including executive and verbal memory.[50]

Other

Sleep disorders are a feature of the disease and can be worsened by medications.[31] Symptoms can manifest as daytime drowsiness (including sudden sleep attacks resembling narcolepsy), disturbances in REM sleep, or insomnia.[31] REM behavior disorder (RBD), in which people act out dreams, sometimes injuring themselves or their bed partner, may begin many years before the development of motor or cognitive features of PD or DLB.[52]

Alterations in the autonomic nervous system can lead to orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure upon standing), oily skin and excessive sweating, urinary incontinence, and altered sexual function.[31] Constipation and impaired stomach emptying (gastric dysmotility) can be severe enough to cause discomfort and even endanger health.[17] Changes in perception may include an impaired sense of smell, disturbed vision, pain, and paresthesia (tingling and numbness).[31] All of these symptoms can occur years before diagnosis of the disease.[31]

Causes

Many risk factors have been proposed, sometimes in relation to theories concerning possible mechanisms of the disease; however, none have been conclusively proven.[53] The most frequently replicated relationships are an increased risk in those exposed to pesticides, and a reduced risk in smokers.[53][54] There is a possible link between PD and H. pylori infection that can prevent the absorption of some drugs including levodopa.[55][56]

Environmental factors and exposures

Exposure to pesticides and a history of head injury have each been linked with Parkinson disease (PD), but the risks are modest. Never having smoked cigarettes, and never drinking caffeinated beverages, are also associated with small increases in risk of developing PD.[46]

Low concentrations of urate in the blood serum is associated with an increased risk of PD.[57]

Drug-Induced Parkinsonism

Different medical drugs have been indicated in cases of parkinsonism. Drug-induced parkinsonism is normally reversible by stopping the offending agent.[58] Drugs include but not are not limited to:

- Phenothiazines (chlorpromazine, promazine, etc.)

- Butyrophenones (haloperidol, benperidol, etc.)

- Metoclopramide

- Tetrabenazine

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) is a drug known for causing irreversible parkinsonism that is commonly used in animal model research.[58][59][60]

Toxin-Induced Parkinsonism

Some toxins can cause parkinsonism. These toxins include but are not limited to manganese and carbon disulfide [61][58][62][63]

Genetics

Research indicates that PD is the product of a complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors.[4] Around 15% of individuals with PD have a first-degree relative who has the disease,[16] and 5–10% of people with PD are known to have forms of the disease that occur because of a mutation in one of several specific genes.[64][65] Harboring one of these gene mutations may not lead to the disease; susceptibility factors put the individual at an increased risk, often in combination with other risk factors, which also affect age of onset, severity and progression.[64] At least 11 autosomal dominant and 9 autosomal recessive gene mutations have been implicated in the development of PD. The autosomal dominant genes include SNCA, PARK3, UCHL1, LRRK2, GIGYF2, HTRA2, EIF4G1, TMEM230, CHCHD2, RIC3, VPS35. Autosomal recessive genes include PRKN, PINK1, PARK7, ATP13A2, PLA2G6, FBXO7, DNAJC6, SYNJ1, and VPS13C. Some genes are x-linked or have unknown inheritance pattern: those include PARK10, PARK12, and PARK16. 22q11 deletion is also known to be associated with PD.[66][65] An autosomal dominant form has been associated with mutations in the LRP10 gene.[12][67]

About 5% of people with PD have mutations in the GBA1 gene.[68] These mutations are present in less than 1% of the unaffected population. The risk of developing PD is increased 20–30 fold if these mutations are present. PD associated with these mutations has the same clinical features, but an earlier age of onset and a more rapid cognitive and motor decline. This gene encodes glucocerebrosidase. Low levels of this enzyme cause Gaucher's disease.

SNCA gene mutations are important in PD because the protein which this gene encodes, alpha-synuclein, is the main component of the Lewy bodies that accumulate in the brains of people with PD.[64] Alpha-synuclein activates ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated), a major DNA damage repair signaling kinase.[69] In addition, alpha-synuclein activates the non-homologous end joining DNA repair pathway. The aggregation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies appears to be a link between reduced DNA repair and brain cell death in PD.[69]

Mutations in some genes, including SNCA, LRRK2 and GBA, have been found to be risk factors for "sporadic" (non-familial) PD.[64] Mutations in the gene LRRK2 are the most common known cause of familial and sporadic PD, accounting for approximately 5% of individuals with a family history of the disease and 3% of sporadic cases.[70][64] A mutation in GBA presents the greatest genetic risk of developing Parkinsons disease.[71]

Several Parkinson-related genes are involved in the function of lysosomes, organelles that digest cellular waste products. It has been suggested that some cases of PD may be caused by lysosomal disorders that reduce the ability of cells to break down alpha-synuclein.[72]

Vascular Parkinsonism

Vascular parkinsonism is the phenomena of the presence of Parkinson's disease symptoms combined with findings of vascular events (such as a cerebral stroke). The damaging of the dopaminergic pathways are similar causes of both vascular parkinsonism and idiopathic Parkinson's Disease, so they can present with many of the same symptoms. Differentiation can be made with careful bedside examination, history taking, and imaging.[73][58][74]

Other identifiable causes of parkinsonism include infections and metabolic derangement. Several neurodegenerative disorders also may present with parkinsonism and are sometimes referred to as "atypical parkinsonism" or "Parkinson plus" syndromes (illnesses with parkinsonism plus some other features distinguishing them from PD). They include multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).[16][75] Dementia with Lewy bodies is another synucleinopathy and it has close pathological similarities with PD, especially with the subset of PD cases with dementia known as Parkinson's disease dementia. The relationship between PD and DLB is complex and incompletely understood.[76] They may represent parts of a continuum with variable distinguishing clinical and pathological features or they may prove to be separate diseases.[76]

Pathophysiology

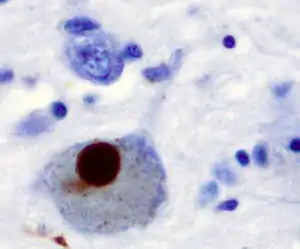

The main pathological characteristics of PD are cell death in the brain's basal ganglia (affecting up to 70% of the dopamine secreting neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta by the end of life).[70] In Parkinson's disease, alpha-synuclein becomes misfolded and clump together with other alpha-synuclein. Cells are unable to remove these clumps and the alpha synuclein becomes cytotoxic, damaging the cells.[11][77] These clumps can be seen in neurons under a microscope and are called Lewy bodies. Loss of neurons is accompanied by the death of astrocytes (star-shaped glial cells) and a significant increase in the number of microglia (another type of glial cell) in the substantia nigra.[78] Braak staging is a way to explain the progression of the parts of the brain affected by Parkinson's disease. According to this staging, PD starts in the medulla and the olfactory bulb before moving to the substantia nigra pars compacta and the rest of the midbrain/basal foerbrain. Movement symptom onset is associated when the disease begins to affect the substantia nigra pars compacta.[14]

- Schematic initial progression of Lewy body deposits in the first stages of Parkinson's disease, as proposed by Braak and colleagues

- Localization of the area of significant brain volume reduction in initial PD compared with a group of participants without the disease in a neuroimaging study, which concluded that brainstem damage may be the first identifiable stage of PD neuropathology[79]

There are five major pathways in the brain connecting other brain areas with the basal ganglia. These are known as the motor, oculo-motor, associative, limbic and orbitofrontal circuits, with names indicating the main projection area of each circuit.[80] All of them are affected in PD, and their disruption explains many of the symptoms of the disease, since these circuits are involved in a wide variety of functions, including movement, attention and learning.[80] Scientifically, the motor circuit has been examined the most intensively.[80]

A particular conceptual model of the motor circuit and its alteration with PD has been of great influence since 1980, although some limitations have been pointed out which have led to modifications.[80] In this model, the basal ganglia normally exert a constant inhibitory influence on a wide range of motor systems, preventing them from becoming active at inappropriate times. When a decision is made to perform a particular action, inhibition is reduced for the required motor system, thereby releasing it for activation. Dopamine acts to facilitate this release of inhibition, so high levels of dopamine function tend to promote motor activity, while low levels of dopamine function, such as occur in PD, demand greater exertions of effort for any given movement. Thus, the net effect of dopamine depletion is to produce hypokinesia, an overall reduction in motor output.[80] Drugs that are used to treat PD, conversely, may produce excessive dopamine activity, allowing motor systems to be activated at inappropriate times and thereby producing dyskinesias.[80]

Brain cell death

There is speculation of several mechanisms by which the brain cells could be lost.[81] One mechanism consists of an abnormal accumulation of the protein alpha-synuclein bound to ubiquitin in the damaged cells. This insoluble protein accumulates inside neurons forming inclusions called Lewy bodies.[70][82] According to the Braak staging, a classification of the disease based on pathological findings proposed by Heiko Braak, Lewy bodies first appear in the olfactory bulb, medulla oblongata and pontine tegmentum; individuals at this stage may be asymptomatic or may have early non-motor symptoms (such as loss of sense of smell, or some sleep or automatic dysfunction). As the disease progresses, Lewy bodies develop in the substantia nigra, areas of the midbrain and basal forebrain and, finally, the neocortex.[70] These brain sites are the main places of neuronal degeneration in PD; however, Lewy bodies may not cause cell death and they may be protective (with the abnormal protein sequestered or walled off). Other forms of alpha-synuclein (e.g., oligomers) that are not aggregated in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites may actually be the toxic forms of the protein.[81][82] In people with dementia, a generalized presence of Lewy bodies is common in cortical areas. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques, characteristic of Alzheimer's disease, are not common unless the person is demented.[78]

Other cell-death mechanisms include proteasomal and lysosomal system dysfunction and reduced mitochondrial activity.[81] Iron accumulation in the substantia nigra is typically observed in conjunction with the protein inclusions. It may be related to oxidative stress, protein aggregation and neuronal death, but the mechanisms are not fully understood.[83]

Diagnosis

A physician will initially assess for Parkinson's disease with a careful medical history and neurological examination.[31] Focus is put on confirming motor symptoms (bradykinesia, rest tremor, etc.) and supporting tests with clinical diagnostic criteria being discussed below. The finding of Lewy bodies in the midbrain on autopsy is usually considered final proof that the person had PD. The clinical course of the illness over time may reveal it is not Parkinson's disease, requiring that the clinical presentation be periodically reviewed to confirm accuracy of the diagnosis.[31][84]

There can be multiple causes of parkinsonism or diseases that look similar. Stroke, certain medications, and toxins can cause "secondary parkinsonism" and needs to be assessed during visit.[14][84] Parkinson-plus syndromes, such as progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy, must also be considered and ruled out appropriately due to different treatment and disease progression (anti-parkinson's medications are typically less effective at controlling symptoms in Parkinson-plus syndromes).[31] Faster progression rates, early cognitive dysfunction or postural instability, minimal tremor, or symmetry at onset may indicate a Parkinson plus disease rather than PD itself.[85]

Medical organizations have created diagnostic criteria to ease and standardize the diagnostic process, especially in the early stages of the disease. The most widely known criteria come from the UK Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders and the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The Queen Square Brain Bank criteria require slowness of movement (bradykinesia) plus either rigidity, resting tremor, or postural instability. Other possible causes of these symptoms need to be ruled out. Finally, three or more of the following supportive features are required during onset or evolution: unilateral onset, tremor at rest, progression in time, asymmetry of motor symptoms, response to levodopa for at least five years, clinical course of at least ten years and appearance of dyskinesias induced by the intake of excessive levodopa.[86]

When PD diagnoses are checked by autopsy, movement disorders experts are found on average to be 79.6% accurate at initial assessment and 83.9% accurate after they have refined their diagnosis at a follow-up examination. When clinical diagnoses performed mainly by nonexperts are checked by autopsy, average accuracy is 73.8%. Overall, 80.6% of PD diagnoses are accurate, and 82.7% of diagnoses using the Brain Bank criteria are accurate.[87]

A task force of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) has proposed diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease as well as research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal disease, but these will require validation against the more established criteria.[88][89]

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) scans of people with PD usually appear normal.[90] MRI has become more accurate in diagnosis of the disease over time, specifically through iron-sensitive T2* and SWI sequences at a magnetic field strength of at least 3T, both of which can demonstrate absence of the characteristic 'swallow tail' imaging pattern in the dorsolateral substantia nigra.[91] In a meta-analysis, absence of this pattern was highly sensitive and specific for the disease.[92] A 2020 meta-analysis found that neuromelanin-MRI had a favorable diagnostic performance in discriminating individuals with Parkinson's from healthy subjects.[93] Diffusion MRI has shown potential in distinguishing between PD and Parkinson-plus syndromes, though its diagnostic value is still under investigation.[90] CT and MRI are also used to rule out other diseases that can be secondary causes of parkinsonism, most commonly encephalitis and chronic ischemic insults, as well as less frequent entities such as basal ganglia tumors and hydrocephalus.[90]

The metabolic activity of dopamine transporters in the basal ganglia can be directly measured with PET and SPECT scans, with the DaTSCAN being a common proprietary version of this study. It has shown high agreement with clinical diagnoses of Parkinson's.[94] Reduced dopamine-related activity in the basal ganglia can help exclude drug-induced Parkinsonism. This finding is not entirely specific, however, and can be seen with both PD and Parkinson-plus disorders.[90] In the United States, DaTSCANs are only FDA approved to distinguish Parkinson’s disease or Parkinsonian syndromes from essential tremor.[95]

Iodine-123-meta-iodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy can help find denervation of the nerves around the heart, which can support a PD diagnosis.[14]

Differential diagnosis

Secondary Parkinsonism - There can be multiple causes of Parkinsonism including drugs, toxins, and vascular incidents (such as strokes). These can be differentiated between with careful history, physical, and appropriate imaging.[58][14][96] This topic is further discussed in the causes section here.

Parkinson-plus syndrome - Multiple diseases can be considered part of the Parkinson's plus group including corticobasal syndrome, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and dementia with lewy bodies. Differential diagnosis can be narrowed down with careful history and physical (especially focused on onset of specific symptoms), progression of the disease, and response to treatment.[97][96] Some key features between them:[58][96]

- Corticobasal syndrome - levodopa-resistance, myoclonus, dystonia, corticosensory loss, apraxia, and non-fluent aphasia.

- Multiple system atrophy - levodopa resistance, rapidly progressive, autonomic failure, stridor, present babinski sign, cerebellar ataxia, and specific MRI findings.

- Progressive supranuclear palsy - levodopa resistance, restrictive vertical gaze, specific MRI findings, and early and different postural difficulties.

- Dementia with Lewy bodies - levodopa resistance, cognitive predominance before motor symptoms, and fluctuating congnitive symptoms. Visual hallucinations are very common in this disease however PD patients can also have those.

Essential tremor - Essential tremor can at first look like parkinsonsim, however there are key differentiators. In essential tremor the tremor will get worse with action (where in PD it gets better), there will be a lack of other symptoms common in PD, and normal DatSCAN.[96][58]

Other conditions that can have similar presentations to PD include:[98][58]

- Arthritis

- Creutzfeld-Jacob Disease

- Dystonia

- Depression

- Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome

- Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17

- Huntington’s disease

- Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification

- Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation

- Normal-pressure hydrocephalus

- Obsessional slowness

- Psychogenic parkinsonism

- Wilson’s disease

Prevention

Exercise in middle age may reduce the risk of Parkinson's disease later in life.[18] Caffeine also appears protective with a greater decrease in risk occurring with a larger intake of caffeinated beverages such as coffee.[99] People who smoke cigarettes or use smokeless tobacco are less likely than non-smokers to develop PD, and the more they have used tobacco, the less likely they are to develop PD. It is not known what underlies this effect. Tobacco use may actually protect against PD, or it may be that an unknown factor both increases the risk of PD and causes an aversion to tobacco or makes it easier to stop using tobacco.[100][101]

Antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, have been proposed to protect against the disease, but results of studies have been contradictory and no positive effect has been proven.[53] The results regarding fat and fatty acids have been contradictory, with various studies reporting protective effects, risk-increasing effects or no effects.[53] There have been preliminary indications that the use of anti-inflammatory drugs and calcium channel blockers may be protective.[4] A 2010 meta-analysis found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (apart from aspirin), have been associated with at least a 15 percent (higher in long-term and regular users) reduction in the incidence of the development of Parkinson's disease.[102]

Management

There is no known cure for Parkinson's disease. Medications, surgery, and physical treatment may provide relief, improve the quality of a persons life, and are much more effective than treatments available for other neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson-plus syndromes.[103] The main families of drugs useful for treating motor symptoms are levodopa (always combined with a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor and sometimes also with a COMT inhibitor, dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors. The stage of the disease and the age at disease onset determine which group is most useful.[103]

Braak staging of Parkinson's disease gives six stages, that can be used to identify early stages, later stages, and late stages.[104] The initial stage in which some disability has already developed and requires pharmacological treatment is followed by later stages associated with the development of complications related to levodopa usage, and a third stage when symptoms unrelated to dopamine deficiency or levodopa treatment may predominate.[104]

Treatment in the first stage aims for an optimal trade-off between symptom control and treatment side-effects. The start of levodopa treatment may be postponed by initially using other medications such as MAO-B inhibitors and dopamine agonists instead, in the hope of delaying the onset of complications due to levodopa use.[105] However, levodopa is still the most effective treatment for the motor symptoms of PD and should not be delayed in people when their quality of life is impaired. Levodopa-related dyskinesias correlate more strongly with duration and severity of the disease than duration of levodopa treatment, so delaying this therapy may not provide much longer dyskinesia-free time than early use.[106]

In later stages the aim is to reduce PD symptoms while controlling fluctuations in the effect of the medication. Sudden withdrawals from medication or its overuse have to be managed.[105] When oral medications are not enough to control symptoms, surgery, deep brain stimulation, subcutaneous waking day apomorphine infusion and enteral dopa pumps may be useful.[107] Late stage PD presents many challenges requiring a variety of treatments including those for psychiatric symptoms particularly depression, orthostatic hypotension, bladder dysfunction and erectile dysfunction.[107] In the final stages of the disease, palliative care is provided to improve a person's quality of life.[108]

Levodopa

The motor symptoms of PD are the result of reduced dopamine production in the brain's basal ganglia. Dopamine does not cross the blood-brain barrier, so it cannot be taken as a medicine to boost the brain's depleted levels of dopamine. However a precursor of dopamine, levodopa, can pass through to the brain where it is readily converted to dopamine, and administration of levodopa temporarily diminishes the motor symptoms of PD. Levodopa has been the most widely used PD treatment for over 40 years.[105]

Only 5–10% of levodopa crosses the blood–brain barrier. Much of the remainder is metabolized to dopamine elsewhere in the body, causing a variety of side effects including nausea, vomiting and orthostatic hypotension.[109] Carbidopa and benserazide are dopa decarboxylase inhibitors which do not cross the blood-brain barrier and inhibit the conversion of levodopa to dopamine outside the brain, reducing side effects and improving the availability of levodopa for passage into the brain. One of these drugs is usually taken along with levodopa, often combined with levodopa in the same pill.[110]

Levodopa-use leads in the long term to the development of complications: involuntary movements called dyskinesias, and fluctuations in the effectiveness of the medication.[105] When fluctuations occur, a person can cycle through phases with good response to medication and reduced PD symptoms ("on" state), and phases with poor response to medication and significant PD symptoms ("off" state).[105] Using lower doses of levodopa may reduce the risk and severity of these levodopa-induced complications.[111] A former strategy to reduce levodopa-related dyskinesia and fluctuations was to withdraw levodopa medication for some time. This is now discouraged since it can bring on dangerous side effects such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[105] Most people with PD will eventually need levodopa and will later develop levodopa-induced fluctuations and dyskinesias.[105]

There are controlled-release versions of levodopa. Older controlled-release levodopa preparations have poor and unreliable absorption and bioavailability and have not demonstrated improved control of PD motor symptoms or a reduction in levodopa-related complications when compared to immediate release preparations. A newer extended-release levodopa preparation does seem to be more effective in reducing fluctuation,s but in many people problems persist. Intestinal infusions of levodopa (Duodopa) can result in striking improvements in fluctuations compared to oral levodopa when the fluctuations are due to insufficient uptake caused by gastroparesis. Other oral, longer acting formulations are under study and other modes of delivery (inhaled, transdermal) are being developed.[110]

COMT inhibitors

During the course of Parkinson's disease, affected people can experience what's known as a "wearing off phenomena" where they have a recurrence of symptoms after a dose of levodopa but right before their next dose.[14] Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), is a protein that degrades levodopa before it can cross the blood-brain barrier and these inhibitors allow for more levodopa to cross.[113] They are normally not used in the management of early symptoms however can be used in conjunction with levodopa/carbidopa when a person is experiencing the "wearing off phenomena" with their motor symptoms.[14]

There are three COMT inhibitors available to treat adults with Parkinson’s Disease and end-of-dose motor fluctuations: opicapone, entacapone and tolcapone.[14] Tolcapone has been available for several years however its usefulness is limited by possible liver damage complications and therefore requires liver function monitoring.[114][58][14][113] Entacapone and opicapone have not been shown to cause significant alterations to liver function.[113][115][116] Licensed preparations of entacapone contain entacapone alone or in combination with carbidopa and levodopa.[117][58][118] Opicapone is a once-daily COMT inhibitor.[119][14]

Dopamine agonists

Several dopamine agonists that bind to dopamine receptors in the brain have similar effects to levodopa.[105] These were initially used as a complementary therapy to levodopa for individuals experiencing levodopa complications (on-off fluctuations and dyskinesias); they are now mainly used on their own as first therapy for the motor symptoms of PD with the aim of delaying the initiation of levodopa therapy and so delaying the onset of levodopa's complications.[105][120] Dopamine agonists include bromocriptine, pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, piribedil, cabergoline, apomorphine and lisuride.

Though dopamine agonists are less effective than levodopa at controlling PD motor symptoms, they are usually effective enough to manage these symptoms in the first years of treatment.[16] Dyskinesias due to dopamine agonists are rare in younger people who have PD but, along with other complications, become more common with older age at onset.[16] Thus dopamine agonists are the preferred initial treatment for younger onset PD, and levodopa is preferred for older onset PD.[16]

Dopamine agonists produce significant, although usually mild, side effects including drowsiness, hallucinations, insomnia, nausea, and constipation.[105] Sometimes side effects appear even at a minimal clinically effective dose, leading the physician to search for a different drug.[105] Agonists have been related to impulse control disorders (such as compulsive sexual activity, eating, gambling and shopping) even more strongly than levodopa.[121] They tend to be more expensive than levodopa.[16]

Apomorphine, a non-orally administered dopamine agonist, may be used to reduce off periods and dyskinesia in late PD.[105] It is administered by intermittent injections or continuous subcutaneous infusions.[105] Since secondary effects such as confusion and hallucinations are common, individuals receiving apomorphine treatment should be closely monitored.[105] Two dopamine agonists that are administered through skin patches (lisuride and rotigotine) and are useful for people in the initial stages and possibly to control off states in those in the advanced state.[122]

MAO-B inhibitors

MAO-B inhibitors (safinamide, selegiline and rasagiline) increase the amount of dopamine in the basal ganglia by inhibiting the activity of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), an enzyme which breaks down dopamine.[105] They have been found to help alleviate motor symptoms when used as monotherapy (on their own) and, when used in conjunction with levodopa, reduce the time spent in the "off" phase. Selegiline has been shown to delay the need for levodopa commencement, suggesting that it might be neuroprotective and slow the progression of the disease (however this has not been proven).[123] An initial study indicated that selegiline in combination with levodopa increased the risk of death, but this has been refuted.[124]

Common side-effects are nausea, dizziness, insomnia, sleepiness, and (in selegiline and rasagiline) orthostatic hypotension.[123][14] Along with dopamine, MAO-Bs are known to increase serotonin, so care must be used when used with certain antidepressants due to a potentially dangerous condition known as serotonin syndrome.[123]

Other drugs

Other drugs such as amantadine and anticholinergics may be useful as treatment of motor symptoms. However, the evidence supporting them lacks quality, so they are not first choice treatments.[105][125] In addition to motor symptoms, PD is accompanied by a diverse range of symptoms. A number of drugs have been used to treat some of these problems.[126] Examples are the use of quetiapine for psychosis, cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia, and modafinil for daytime sleepiness.[126][127] In 2016 pimavanserin was approved for the management of Parkinson's disease psychosis.[128]

Doxepin and rasagline may reduce physical fatigue in PD.[129]

Surgery

Treating motor symptoms with surgery was once a common practice, but since the discovery of levodopa, the number of operations has declined.[130] Studies in the past few decades have led to great improvements in surgical techniques, so that surgery is again being used in people with advanced PD for whom drug therapy is no longer sufficient.[130] Surgery for PD can be divided in two main groups: lesional and deep brain stimulation (DBS). Target areas for DBS or lesions include the thalamus, the globus pallidus or the subthalamic nucleus.[130] Deep brain stimulation is the most commonly used surgical treatment, developed in the 1980s by Alim Louis Benabid and others. It involves the implantation of a medical device called a neurostimulator, which sends electrical impulses to specific parts of the brain. DBS is recommended for people who have PD with motor fluctuations and tremor inadequately controlled by medication, or to those who are intolerant to medication, as long as they do not have severe neuropsychiatric problems.[131] Other, less common, surgical therapies involve intentional formation of lesions to suppress overactivity of specific subcortical areas. For example, pallidotomy involves surgical destruction of the globus pallidus to control dyskinesia.[130]

Four areas of the brain have been treated with neural stimulators in PD.[132] These are the globus pallidus interna, thalamus, subthalamic nucleus and the pedunculopontine nucleus. DBS of the globus pallidus interna improves motor function while DBS of the thalamic DBS improves tremor but has little effect on bradykinesia or rigidity. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus is usually avoided if a history of depression or neurocognitive impairment is present. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus is associated with reduction in medication. Pedunculopontine nucleus DBS remains experimental at present. Generally DBS is associated with 30–60% improvement in motor score evaluations.

Rehabilitation

Exercise programs are recommended in people with Parkinson's disease.[18] There is some evidence that speech or mobility problems can improve with rehabilitation, although studies are scarce and of low quality.[133][134] Regular physical exercise with or without physical therapy can be beneficial to maintain and improve mobility, flexibility, strength, gait speed, and quality of life.[134] When an exercise program is performed under the supervision of a physiotherapist, there are more improvements in motor symptoms, mental and emotional functions, daily living activities, and quality of life compared to a self-supervised exercise program at home.[135] In terms of improving flexibility and range of motion for people experiencing rigidity, generalized relaxation techniques such as gentle rocking have been found to decrease excessive muscle tension. Other effective techniques to promote relaxation include slow rotational movements of the extremities and trunk, rhythmic initiation, diaphragmatic breathing, and meditation techniques.[136] As for gait and addressing the challenges associated with the disease such as hypokinesia (slowness of movement), shuffling and decreased arm swing; physiotherapists have a variety of strategies to improve functional mobility and safety. Areas of interest with respect to gait during rehabilitation programs focus on, but are not limited to improving gait speed, the base of support, stride length, trunk and arm swing movement. Strategies include utilizing assistive equipment (pole walking and treadmill walking), verbal cueing (manual, visual and auditory), exercises (marching and PNF patterns) and altering environments (surfaces, inputs, open vs. closed).[137] Strengthening exercises have shown improvements in strength and motor function for people with primary muscular weakness and weakness related to inactivity with mild to moderate Parkinson's disease. However, reports show a significant interaction between strength and the time the medications was taken. Therefore, it is recommended that people with PD should perform exercises 45 minutes to one hour after medications when they are at their best.[138] Also, due to the forward flexed posture, and respiratory dysfunctions in advanced Parkinson's disease, deep diaphragmatic breathing exercises are beneficial in improving chest wall mobility and vital capacity.[139] Exercise may improve constipation.[17] It is unclear if exercise reduces physical fatigue in PD.[129]

One of the most widely practiced treatments for speech disorders associated with Parkinson's disease is the Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT).[133][140] Speech therapy and specifically LSVT may improve speech.[133] Occupational therapy (OT) aims to promote health and quality of life by helping people with the disease to participate in as many of their daily living activities as possible.[133] There have been few studies on the effectiveness of OT and their quality is poor, although there is some indication that it may improve motor skills and quality of life for the duration of the therapy.[133][141]

Palliative care

Palliative care is specialized medical care for people with serious illnesses, including Parkinson's. The goal of this speciality is to improve quality of life for both the person with Parkinson's and the family by providing relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of illnesses.[142] As Parkinson's is not a curable disease, all treatments are focused on slowing decline and improving quality of life, and are therefore palliative in nature.[143]

Palliative care should be involved earlier, rather than later in the disease course.[144][145] Palliative care specialists can help with physical symptoms, emotional factors such as loss of function and jobs, depression, fear, and existential concerns.[144][145][146]

Along with offering emotional support to both the affected person and family, palliative care serves an important role in addressing goals of care. People with Parkinson's may have many difficult decisions to make as the disease progresses such as wishes for feeding tube, non-invasive ventilator, and tracheostomy; wishes for or against cardiopulmonary resuscitation; and when to use hospice care.[143] Palliative care team members can help answer questions and guide people with Parkinson's on these complex and emotional topics to help them make the best decision based on their own values.[145][147]

Muscles and nerves that control the digestive process may be affected by PD, resulting in constipation and gastroparesis (food remaining in the stomach for a longer period than normal).[17] A balanced diet, based on periodical nutritional assessments, is recommended and should be designed to avoid weight loss or gain and minimize consequences of gastrointestinal dysfunction.[17] As the disease advances, swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) may appear. In such cases it may be helpful to use thickening agents for liquid intake and an upright posture when eating, both measures reducing the risk of choking. Gastrostomy to deliver food directly into the stomach is possible in severe cases.[17]

Levodopa and proteins use the same transportation system in the intestine and the blood–brain barrier, thereby competing for access.[17] When they are taken together, this results in a reduced effectiveness of the drug.[17] Therefore, when levodopa is introduced, excessive protein consumption is discouraged and well balanced Mediterranean diet is recommended. In advanced stages, additional intake of low-protein products such as bread or pasta is recommended for similar reasons.[17] To minimize interaction with proteins, levodopa should be taken 30 minutes before meals.[17] At the same time, regimens for PD restrict proteins during breakfast and lunch, allowing protein intake in the evening.[17]

Prognosis

|

no data

< 5

5–12.5

12.5–20

20–27.5

27.5–35

35–42.5

|

42.5–50

50–57.5

57.5–65

65–72.5

72.5–80

> 80

|

PD invariably progresses with time. A severity rating method known as the Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale (UPDRS) is the most commonly used metric for clinical study. A modified version known as the MDS-UPDRS is also sometimes used. An older scaling method known as the Hoehn and Yahr scale (originally published in 1967), and a similar scale known as the Modified Hoehn and Yahr scale, have also been commonly used. The Hoehn and Yahr scale defines five basic stages of progression.

Motor symptoms, if not treated, advance aggressively in the early stages of the disease and more slowly later. Untreated, individuals are expected to lose independent ambulation after an average of eight years and be bedridden after ten years.[148] However, it is uncommon to find untreated people nowadays. Medication has improved the prognosis of motor symptoms, while at the same time it is a new source of disability, because of the undesired effects of levodopa after years of use.[148] In people taking levodopa, the progression time of symptoms to a stage of high dependency from caregivers may be over 15 years.[148] However, it is hard to predict what course the disease will take for a given individual.[148] Age is the best predictor of disease progression.[81] The rate of motor decline is greater in those with less impairment at the time of diagnosis, while cognitive impairment is more frequent in those who are over 70 years of age at symptom onset.[81]

Since current therapies improve motor symptoms, disability at present is mainly related to non-motor features of the disease.[81] Nevertheless, the relationship between disease progression and disability is not linear. Disability is initially related to motor symptoms.[148] As the disease advances, disability is more related to motor symptoms that do not respond adequately to medication, such as swallowing/speech difficulties, and gait/balance problems; and also to levodopa-induced complications, which appear in up to 50% of individuals after 5 years of levodopa usage.[148] Finally, after ten years most people with the disease have autonomic disturbances, sleep problems, mood alterations and cognitive decline.[148] All of these symptoms, especially cognitive decline, greatly increase disability.[81][148]

The life expectancy of people with PD is reduced.[148] Mortality ratios are around twice those of unaffected people.[148] Cognitive decline and dementia, old age at onset, a more advanced disease state and presence of swallowing problems are all mortality risk factors. On the other hand, a disease pattern mainly characterized by tremor as opposed to rigidity predicts an improved survival.[148] Death from aspiration pneumonia is twice as common in individuals with PD as in the healthy population.[148]

In 2016 PD resulted in about 211,000 deaths globally, an increase of 161% since 1990.[149] The death rate increased by 19% to 1.81 per 100,000 people during that time.[149]

Epidemiology

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer's disease and affects approximately seven million people globally and one million people in the United States.[38][53][150] The proportion in a population at a given time is about 0.3% in industrialized countries. PD is more common in the elderly and rates rise from 1% in those over 60 years of age to 4% of the population over 80.[53] The mean age of onset is around 60 years, although 5–10% of cases, classified as young onset PD, begin between the ages of 20 and 50.[16] Males are more often affected than females at a ratio of around 3:2.[4] PD may be less prevalent in those of African and Asian ancestry, although this finding is disputed.[53] The number of new cases per year of PD is between 8 and 18 per 100,000 person–years.[53]

The age adjusted rate of Parkinson's disease in Estonia is 28.0/100,000 person years.[151] The Estonian rate has been stable between 2000 and 2019.[151]

History

Several early sources, including an Egyptian papyrus, an Ayurvedic medical treatise, the Bible, and Galen's writings, describe symptoms resembling those of PD.[152] After Galen there are no references unambiguously related to PD until the 17th century.[152] In the 17th and 18th centuries, several authors wrote about elements of the disease, including Sylvius, Gaubius, Hunter and Chomel.[152][153][154]

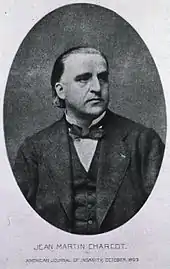

In 1817 an English doctor, James Parkinson, published his essay reporting six cases of paralysis agitans.[21] An Essay on the Shaking Palsy described the characteristic resting tremor, abnormal posture and gait, paralysis and diminished muscle strength, and the way that the disease progresses over time.[19][155] Early neurologists who made further additions to the knowledge of the disease include Trousseau, Gowers, Kinnier Wilson and Erb, and most notably Jean-Martin Charcot, whose studies between 1868 and 1881 were a landmark in the understanding of the disease.[21] Among other advances, he made the distinction between rigidity, weakness and bradykinesia.[21] He also championed the renaming of the disease in honor of James Parkinson.[21]

In 1912 Frederic Lewy described microscopic particles in affected brains, later named "Lewy bodies".[21] In 1919 Konstantin Tretiakoff reported that the substantia nigra was the main cerebral structure affected, but this finding was not widely accepted until it was confirmed by further studies published by Rolf Hassler in 1938.[21] The underlying biochemical changes in the brain were identified in the 1950s, due largely to the work of Arvid Carlsson on the neurotransmitter dopamine and Oleh Hornykiewicz on its role on PD.[156] In 1997, alpha-synuclein was found to be the main component of Lewy bodies by Spillantini, Trojanowski, Goedert and others.[82]

Anticholinergics and surgery (lesioning of the corticospinal pathway or some of the basal ganglia structures) were the only treatments until the arrival of levodopa, which reduced their use dramatically.[153][157] Levodopa was first synthesized in 1911 by Casimir Funk, but it received little attention until the mid 20th century.[156] It entered clinical practice in 1967 and brought about a revolution in the management of PD.[156][158] By the late 1980s deep brain stimulation introduced by Alim Louis Benabid and colleagues at Grenoble, France, emerged as a possible treatment.[159]

Society and culture

Cost

The costs of PD to society are high, but precise calculations are difficult due to methodological issues in research and differences between countries.[160] The annual cost in the UK is estimated to be between £49 million and £3.3 billion, while the cost per affected person per year in the U.S. is probably around $10,000 and the total burden around $23 billion.[160] The largest share of direct cost comes from inpatient care and nursing homes, while the share coming from medication is substantially lower.[160] Indirect costs are high, due to reduced productivity and the burden on caregivers.[160] In addition to economic costs, PD reduces quality of life of those with the disease and their caregivers.[160]

Advocacy

The birthday of James Parkinson, 11 April, has been designated as World Parkinson's Day.[21] A red tulip was chosen by international organizations as the symbol of the disease in 2005: it represents the James Parkinson Tulip cultivar, registered in 1981 by a Dutch horticulturalist.[161] Advocacy organizations include the National Parkinson Foundation, which has provided more than $180 million in care, research and support services since 1982,[162] Parkinson's Disease Foundation, which has distributed more than $115 million for research and nearly $50 million for education and advocacy programs since its founding in 1957 by William Black;[163][164] the American Parkinson Disease Association, founded in 1961;[165] and the European Parkinson's Disease Association, founded in 1992.[166]

Notable cases

Actor Michael J. Fox has PD and has greatly increased the public awareness of the disease.[22] After diagnosis, Fox embraced his Parkinson's in television roles, sometimes acting without medication, in order to further illustrate the effects of the condition. He has written two autobiographies in which his fight against the disease plays a major role,[167] and appeared before the United States Congress without medication to illustrate the effects of the disease.[167] The Michael J. Fox Foundation aims to develop a cure for Parkinson's disease.[167] Fox received an honorary doctorate in medicine from Karolinska Institutet for his contributions to research in Parkinson's disease.[168]

Professional cyclist and Olympic medalist Davis Phinney, who was diagnosed with young onset Parkinson's at age 40, started the Davis Phinney Foundation in 2004 to support Parkinson's research, focusing on quality of life for people with the disease.[23][169]

Boxer Muhammad Ali showed signs of Parkinson's when he was 38, but was not diagnosed until he was 42, and has been called the "World's most famous Parkinson's patient".[24] Whether he had PD or parkinsonism related to boxing is unresolved.[170][171]

Research

There are no approved disease modifying drugs (drugs that target the causes or damage) for Parkinson's, this is a major focus of Parkinson's research.[172] Active research directions include the search for new animal models of the disease and studies of the potential usefulness of gene therapy, stem cell transplants and neuroprotective agents.[172]

Animal models

PD is not known to occur naturally in any species other than humans, although animal models which show some features of the disease are used in research. The appearance of parkinsonism in a group of drug addicts in the early 1980s who consumed a contaminated batch of the synthetic opiate MPPP led to the discovery of the chemical MPTP as an agent that causes parkinsonism in non-human primates as well as in humans.[173] Other predominant toxin-based models employ the insecticide rotenone, the herbicide paraquat and the fungicide maneb.[174] Models based on toxins are most commonly used in primates. Transgenic rodent models that replicate various aspects of PD have been developed.[175] The use of neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine, creates a model of Parkinson's disease in rats by targeting and destroying dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway when injected into the substantia nigra.[176]

Gene therapy

Gene therapy typically involves the use of a non-infectious virus (i.e., a viral vector such as the adeno-associated virus) to shuttle genetic material into a part of the brain. Several approaches have been tried. These approaches have involved the expression of growth factors to try to prevent damage (Neurturin – a GDNF-family growth factor), and enzymes such as glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD – the enzyme that produces GABA), tyrosine hydroxylase (the enzyme that produces L-DOPA) and catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT – the enzyme that converts L-DOPA to dopamine). There have been no reported safety concerns, but the approaches have largely failed in phase 2 clinical trials.[172] The delivery of GAD showed promise in phase 2 trials in 2011, but whilst effective at improving motor function was inferior to DBS. Follow-up studies in the same cohort have suggested persistent improvement.[177]

Neuroprotective treatments

Investigations on neuroprotection are at the forefront of PD research. Several molecules have been proposed as potential treatments.[81] However, none of them have been conclusively demonstrated to reduce degeneration.[81] Agents currently under investigation include, antiglutamatergics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (selegiline, rasagiline), promitochondrials (coenzyme Q10, creatine), calcium channel blockers (isradipine) and growth factors (GDNF).[81] Reducing alpha-synuclein pathology is a major focus of preclinical research.[178] A vaccine that primes the human immune system to destroy alpha-synuclein, PD01A (developed by Austrian company, Affiris), entered clinical trials and a phase 1 report in 2020 suggested safety and tolerability.[179][180] In 2018, an antibody, PRX002/RG7935, showed preliminary safety evidence in stage I trials supporting continuation to stage II trials.[181]

Cell-based therapies

Since early in the 1980s, fetal, porcine, carotid or retinal tissues have been used in cell transplants, in which dissociated cells are injected into the substantia nigra in the hope that they will incorporate themselves into the brain in a way that replaces the dopamine-producing cells that have been lost.[81] These sources of tissues have been largely replaced by induced pluripotent stem cell derived dopaminergic neurons as this is thought to represent a more feasible source of tissue. There was initial evidence of mesencephalic dopamine-producing cell transplants being beneficial, double-blind trials to date have not determined whether there is a long-term benefit.[182] An additional significant problem was the excess release of dopamine by the transplanted tissue, leading to dyskinesia.[182] In 2020, a first in human clinical trial reported the transplantation of induced pluripotent stem cells into the brain of a person suffering from Parkinson's disease.[183]

Other

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation temporarily improves levodopa-induced dyskinesias.[184] Its usefulness in PD is an open research topic.[185] Several nutrients have been proposed as possible treatments; however there is no evidence that vitamins or food additives improve symptoms.[186] There is no evidence to substantiate that acupuncture and practice of Qigong, or T'ai chi, have any effect on the course of the disease or symptoms.[187][188][189]

The role of the gut–brain axis and the gut flora in Parkinsons became a topic of study in the 2010s, starting with work in germ-free transgenic mice, in which fecal transplants from people with PD had worse outcomes. Some studies in humans have shown a correlation between patterns of dysbiosis in the gut flora in the people with PD, and these patterns, along with a measure of severity of constipation, could diagnose PD with a 90% specificity but only a 67% sensitivity. As of 2017 some scientists hypothesized that changes in the gut flora might be an early site of PD pathology, or might be part of the pathology.[190][191] Evidence indicates that gut microbiota can produce lipopolysaccharide that interferes with the normal function of α-synuclein.[192]

Ventures have been undertaken to explore antagonists of adenosine receptors (specifically A2A) as an avenue for novel drugs for Parkinson's.[193] Of these, istradefylline has emerged as the most successful medication and was approved for medical use in the United States in 2019.[194] It is approved as an add-on treatment to the levodopa/carbidopa regime.[194]

References

- "Parkinson's Disease Information Page". NINDS. 30 June 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Sveinbjornsdottir S (October 2016). "The clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 139 Suppl 1: 318–24. doi:10.1111/jnc.13691. PMID 27401947.

- Carroll WM (2016). International Neurology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 188. ISBN 978-1118777367. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Kalia LV, Lang AE (August 2015). "Parkinson's disease". Lancet. 386 (9996): 896–912. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61393-3. PMID 25904081. S2CID 5502904.

- Ferri FF (2010). "Chapter P". Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 978-0323076999.

- Macleod AD, Taylor KS, Counsell CE (November 2014). "Mortality in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Movement Disorders. 29 (13): 1615–22. doi:10.1002/mds.25898. PMID 24821648.

- GBD 2015 Disease Injury Incidence Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- GBD 2015 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- "Understanding Parkinson's". Parkinson's Foundation. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Han, Ji Won; Ahn, Yebin D.; Kim, Won-Seok; Shin, Cheol Min; Jeong, Seong Jin; Song, Yoo Sung; Bae, Yun Jung; Kim, Jong-Min (19 November 2018). "Psychiatric Manifestation in Patients with Parkinson's Disease". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 33 (47): e300. doi:10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e300. ISSN 1598-6357. PMC 6236081. PMID 30450025.

- Villar-Piqué, Anna; Lopes da Fonseca, Tomás; Outeiro, Tiago Fleming (October 2016). "Structure, function and toxicity of alpha-synuclein: the Bermuda triangle in synucleinopathies". Journal of Neurochemistry. 139: 240–255. doi:10.1111/jnc.13249. PMID 26190401. S2CID 11420411.

- Quadri M, Mandemakers W, Grochowska MM, et al. (July 2018). "LRP10 genetic variants in familial Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a genome-wide linkage and sequencing study". The Lancet. Neurology. 17 (7): 597–608. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30179-0. PMID 29887161. S2CID 47009438.

- Barranco Quintana JL, Allam MF, Del Castillo AS, Navajas RF (February 2009). "Parkinson's disease and tea: a quantitative review". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 28 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/07315724.2009.10719754. PMID 19571153. S2CID 26605333.

- Armstrong, Melissa J.; Okun, Michael S. (11 February 2020). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review". JAMA. 323 (6): 548–560. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.22360. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 32044947.

- Mosley AD (2010). The encyclopedia of Parkinson's disease (2nd ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 89. ISBN 978-1438127491. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR (May 2004). "Parkinson's disease". Lancet. 363 (9423): 1783–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16305-8. PMID 15172778. S2CID 35364322.

- Barichella M, Cereda E, Pezzoli G (October 2009). "Major nutritional issues in the management of Parkinson's disease". Movement Disorders. 24 (13): 1881–92. doi:10.1002/mds.22705. hdl:2434/67795. PMID 19691125. S2CID 23528416.

- Ahlskog JE (July 2011). "Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease?". Neurology. 77 (3): 288–94. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e318225ab66. PMC 3136051. PMID 21768599.

- Parkinson J (1817). An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. London: Whittingham and Roland for Sherwood, Neely, and Jones. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Shulman JM, De Jager PL, Feany MB (February 2011) [25 October 2010]. "Parkinson's disease: genetics and pathogenesis". Annual Review of Pathology. 6: 193–222. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130242. PMID 21034221. S2CID 8328666.

- Lees AJ (September 2007). "Unresolved issues relating to the shaking palsy on the celebration of James Parkinson's 250th birthday". Movement Disorders. 22 Suppl 17 (Suppl 17): S327–34. doi:10.1002/mds.21684. PMID 18175393. S2CID 9471754.

- Davis P (3 May 2007). "Michael J. Fox". The TIME 100. Time. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- Macur J (26 March 2008). "For the Phinney Family, a Dream and a Challenge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

About 1.5 million Americans have received a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease, but only 5 to 10 percent learn of it before age 40, according to the National Parkinson Foundation. Davis Phinney was among the few.

- Brey RL (April 2006). "Muhammad Ali's Message: Keep Moving Forward". Neurology Now. 2 (2): 8. doi:10.1097/01222928-200602020-00003. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Alltucker K (31 July 2018). "Alan Alda has Parkinson's disease: Here are 5 things you should know". USA Today. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Schrag A (2007). "Epidemiology of movement disorders". In Tolosa E, Jankovic JJ (eds.). Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 50–66. ISBN 978-0-7817-7881-7.

- Galpern WR, Lang AE (March 2006) [17 February 2006]. "Interface between tauopathies and synucleinopathies: a tale of two proteins". Annals of Neurology. 59 (3): 449–58. doi:10.1002/ana.20819. PMID 16489609. S2CID 19395939.

- Marras, C.; Lang, A. (1 April 2013). "Parkinson's disease subtypes: lost in translation?". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 84 (4): 409–415. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-303455. ISSN 0022-3050. PMID 22952329.

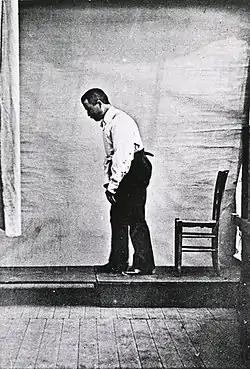

- Photo by Arthur Londe from Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpètrière, vol. 5, p. 226

- Charcot J, Sigerson G (1879). Lectures on the diseases of the nervous system (Second ed.). Philadelphia: Henry C. Lea. p. 113.

The strokes forming the letters are very irregular and sinuous, whilst the irregularities and sinuosities are of a very limited width. (...) the down-strokes are all, with the exception of the first letter, made with comparative firmness and are, in fact, nearly normal – the finer up-strokes, on the contrary, are all tremulous in appearance (...).

- Jankovic J (April 2008). "Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 79 (4): 368–76. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. PMID 18344392. Archived from the original on 19 August 2015.

- Cooper G, Eichhorn G, Rodnitzky RL (2008). "Parkinson's disease". In Conn PM (ed.). Neuroscience in medicine. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 508–12. ISBN 978-1-60327-454-8.

- Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T (June 2009). "Parkinson's disease". Lancet. 373 (9680): 2055–66. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. PMID 19524782. S2CID 42608600.

- Banich MT, Compton RJ (2011). "Motor control". Cognitive neuroscience. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage learning. pp. 108–44. ISBN 978-0-8400-3298-0.

- Longmore M, Wilkinson IB, Turmezei T, Cheung CK (4 January 2007). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 486. ISBN 978-0-19-856837-7.

- Fung VS, Thompson PD (2007). "Rigidity and spasticity". In Tolosa E, Jankovic (eds.). Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 504–13. ISBN 978-0-7817-7881-7.

- O'Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ (2007). "Parkinson's Disease". Physical Rehabilitation (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. pp. 856–57.

- Yao SC, Hart AD, Terzella MJ (May 2013). "An evidence-based osteopathic approach to Parkinson disease". Osteopathic Family Physician. 5 (3): 96–101. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2013.01.003.

- Hallett M, Poewe W (13 October 2008). Therapeutics of Parkinson's Disease and Other Movement Disorders. John Wiley & Sons. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-470-71400-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD (May 1967). "Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality". Neurology. 17 (5): 427–42. doi:10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. PMID 6067254.

- Pahwa R, Lyons KE (25 March 2003). Handbook of Parkinson's Disease (Third ed.). CRC Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-203-91216-4. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Caballol N, Martí MJ, Tolosa E (September 2007). "Cognitive dysfunction and dementia in Parkinson disease". Movement Disorders. 22 Suppl 17 (Suppl 17): S358–66. doi:10.1002/mds.21677. PMID 18175397. S2CID 3229727.

- Parker KL, Lamichhane D, Caetano MS, Narayanan NS (October 2013). "Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease and timing deficits". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 7: 75. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075. PMC 3813949. PMID 24198770.

- Gomperts SN (April 2016). "Lewy Body Dementias: Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Parkinson Disease Dementia". Continuum (Minneap Minn) (Review). 22 (2 Dementia): 435–63. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000309. PMC 5390937. PMID 27042903.

- Garcia-Ptacek S, Kramberger MG (September 2016). "Parkinson Disease and Dementia". Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 29 (5): 261–70. doi:10.1177/0891988716654985. PMID 27502301. S2CID 21279235.

- Noyce AJ, Bestwick JP, Silveira-Moriyama L, et al. (December 2012). "Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease". Annals of Neurology (Review). 72 (6): 893–901. doi:10.1002/ana.23687. PMC 3556649. PMID 23071076.

- Ffytche, Dominic H.; Creese, Byron; Politis, Marios; Chaudhuri, K. Ray; Weintraub, Daniel; Ballard, Clive; Aarsland, Dag (1 February 2017). "The psychosis spectrum in Parkinson disease". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 13 (2): 81–95. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2016.200. ISSN 1759-4766. PMC 5656278. PMID 28106066.