Pavel Tcacenco

Pavel Tcacenco or Tkachenko (Russian: Павел Дмитриевич Ткаченко; born Yakov Antipov or Antip, Russian: Яков Яковлевич Антипов; 7 April?, 1892/1899/1901 – 5 September 1926) was an Imperial Russian-born Romanian communist activist, a leading member of the communist movements of Bessarabia and Romania in the 1920s.

Pavel Tcacenco | |

|---|---|

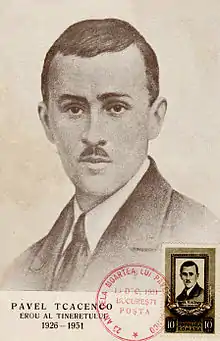

Pavel Tcacenco on a 1952 Romanian postcard | |

| Born | Yakov Antip 1892/1899/1901 |

| Died | 5 September 1926 |

| Occupation | Professional revolutionary |

Early life and the Russian Revolution

Yakov Antipov was born in the village of Novosavitskaya (nowadays part of the unrecognized Trans-Dniester Republic) to Yakov Antipov, a railway worker, and Smaragda Dimitrievna. The date of his birth is unsure. According to his own declaration on the occasion of his arrest in 1926, he was born in 1899, while his Siguranța (Romanian secret police) file noted 7 April 1899 as his birth date.[1] However, an article published in 1926 in the newspaper Izvestia of Odessa, mentions 1892 as the year of his birth,[2] while several late Soviet sources present April 1901 as the month of his birth.[3][4]

In 1902 the whole family relocated to Bendery. At the age of 14 he began working as an apprentice in the local railway workshops, around this time becoming a supporter of socialism.[3] After finishing a local high school in 1917, he left for Petrograd to enrol in Law school.[5][3] There he joined the Russian revolutionary movement,[3][5] adopting the pseudonym Tcacenco.[6] He participated in the Russian Revolutions of February and October.[6] In August 1917 he joined the Red Guards and fought against the forces of White general Lavr Kornilov. In late 1917 Tcacenco returned to Bendery, where he helped organise the local supporters of the Bolsheviks,[5] and became one of the leaders of the revolutionary youth organisation.[3]

Activism in Romania

After Bessarabia joined Greater Romania, a large part of the communist organisation in Chișinău, the Bessarabian capital, was arrested by the new authorities and put under trial in the Trial of the 108. Tcacenco received the task of restoring the organisation, and in October 1919 he was elected secretary of the Chișinău communist committee. Later he would be elected secretary of the regional organisation of the party in Bessarabia.[5] Tcacenco was one of the founders of an illegal typography in Chișinău, and was the editor of Bolșevicul basarabean ("The Bessarabian Bolshevik", in Moldavian), and Bessarabskiy kommunist ("The Bessarabian Communist", in Russian). He also contributed to the restoration of the communist youth organisation in the main city of Bessarabia, and tightened contacts with the local communist-influenced trade unions.[3] At the same time, Tcacenco established contacts with Alecu Constantinescu, a leading member of Bucharest's nascent communist movement. The contacts between the two organisations were however soon interrupted as Tcacenco was arrested in Chișinău on 6/7 August 1920, along with several communist activists.[6] Tcacenco succeeded in escaping custody on 17 August 1920, leaving for Iași. On 19 February 1921, the Chișinău court-martial convicted him in absentia to death.[6][3]

In Iași, Tcacenco assisted in the organisation of the still chaotic local workers' movement. In March 1921 he participated at the Iași Conference of communist organisations, and was elected in the central committee of the Conference.[6][3] During the debates, he supported the creation of an unified communist movement, part of the Socialist Party of Romania, and opposed the creation of several provincial parties, as proposed by other delegates. He and most of the delegates to the Conference were arrested by the Romanian authorities on 26 March and during the following days. Tcacenco was included in the group of communists tried in the Dealul Spirii Trial (January–June 1922), when the National-Liberal government attempted to eliminate the Communist Party by making it responsible for a bomb attack on the Romanian Senate by anarchist Max Goldstein.[7][3] During the trial, Tcacenco acknowledged he had participated in distributing communist newspapers and manifestos, but denied any connection with the bomb attack.[7] Most of the defendants were ultimately amnestied under public pressure, however Tcacenco received a 2-year jail sentence.[7][3]

The Supreme Council of Re-examination annulled the sentence on 22 September, and disposed a retrial to take place at the War Council of the 5th Army Corps, in Constanța. As the legal proceedings were delayed, Tcacenco escaped custody again on 2 April 1923, and left for Bucharest.[7] He joined the local communist movement, however he was quickly re-apprehended by the authorities. Back in Constanța, the court decided his 1921 activities had a political character, thus falling under the royal amnesty of 1922.[3][8] Nevertheless, he was not set free, as he was sent to Chișinău for a retrial of the February 1921 decision. In August 1923 the sentence was quashed, but Tcacenco was ordered to leave the country in 30 days. He subsequently fled Romania, settling temporarily in Prague, Czechoslovakia.[8]

Exile and demise

Tcacenco eventually made his way into the Soviet Union, where he worked for the Joint State Political Directorate in Moscow. In February 1924 Tcacenco, Grigory Kotovsky, Solomon Timov and other Bessarabian and Romanian communists sent a letter to the Central Committees of the Communist Parties of Russia and Ukraine, requesting the formation of a Moldovan national territory.[3] Soon after, a Moldavian Autonomous Oblast would be created on the left bank of the Dniester, on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR. Later that year, Tcacenco left for Vienna, where he worked for the apparatus of the Comintern.[5] In August 1924, at the Third Congress of the Communist Party of Romania, he was elected a member in the Central Committee,[8] and in March and April 1925 he represented the party in the Executive Committee of the Communist International. There he participated in the political, trade union and peasant commissions.[5] Tcacenco returned to Romania for a short time in July 1925, reintegrating in the local communist movement, however he fled again to Prague as he was notified of an imminent arrest. He succeeded in coming back to Bucharest in 1926, despite a Siguranța order disposing his arrest at the border. In Romania, he agitated for the Workers' and Peasants' Bloc, a legal front organization of the Romanian Communist Party during the 1926 electoral campaign. Tcacenco was a supporter of a united front comprising, besides the Bloc, the Peasants' Party, the National Party and the People's Party. [8]

On 15 August 1926, during a meeting with communist leaders Boris Stefanov and Timotei Marin, the group was surrounded by the police. Tcacenco was shot, but succeeded in escaping, only to be captured later that day.[9] He was sent to Tighina for trial, but never appeared before the court, as he was killed by the Romanian secret police.[5][10] The exact details of his death are disputed. According to one version, he was killed by the Siguranța in Chișinău.[3] Another version posits that he escaped his guards in Chișinău with the help of local communists, only to be captured the following days near Soroca, while attempting to cross the Dniester River in the Soviet Union, and executed.[11] According to a third account, he was shot in Vesterniceni, near Chișinău, while attempting to escape.[12] The location of his remains is unknown.[11]

Legacy

After World War II, as the Romanian Communist Party gained power in Romania, Tcacenco was honoured by the official propaganda along other young communists killed by the previous Romanian governments. After 1970, they were all gradually removed from official discourse, as the personality cult of president Nicolae Ceaușescu singularised the Romanian leader as a hero of the communist youth.[10]

Tcacenco was also celebrated in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. His name was adopted for several enterprises, cultural institutions, and streets bore his name in Chișinău, Bender, and Tiraspol. A monument and a museum dedicated to Tcacenco are found in Bender, while a bust was placed in Tiraspol.[3]

Notes

- Mușat 1970, p. 114.

- Muşat 1970, p. 114.

- Bobeico 1976, p. 409.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Lazić & Drachkovitch 1986, p. 470.

- Muşat 1970, p. 115.

- Muşat 1970, p. 116.

- Muşat 1970, p. 117.

- Muşat 1970, p. 118.

- Stănescu & Catalan 2010, p. 14.

- Muşat 1970, p. 119.

- Bendery 1408–2008.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pavel Tcacenco. |

- Muşat, Ştefan (1970). "Pavel Antip-Tcacenco". Anale de Istorie (in Romanian). Bucharest: Institutul de Studii Istorice și Social-Politice de pe lîngă C.C. al P.C.R. XVI (4): 114–118.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bobeico, Ivan (1976). "ТКАЧЕНКО Павел Дмитриевич" [TKACHENKO Pavel Dmitrievich]. In Varticean, Iosif (ed.). Енчиклопедия Советикэ Молдовеняскэ (in Romanian). 6. Chişinău: Academy of Sciences of the MSSR. p. 409.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lazić, Branko M.; Drachkovitch, Milorad M. (1986). Biographical dictionary of the Comintern. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-8401-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Ткаченко Павел Дмитриевич" [Tkachenko Pavel Dmitrievich]. Бендеры 1408–2008 (in Russian). Aleksandr Tikhonov. 2008–2009. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Stănescu, Mircea; Catalan, Gabriel (2010). "Fondul C.C. al U.T.C. Secţia Cadre-Litera A (1945–1989)" [CC of the UTC fund, Cadres section – Letter A (1945–1989)] (PDF) (in Romanian). National Archives of Romania. Retrieved 5 November 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)