Peace of Vienna (1725)

The Peace of Vienna (often referred to as the First Treaty of Vienna) was a series of four treaties signed between 30 April 1725 and 5 November 1725 by the Habsburg Monarchy, the Holy Roman Empire (in accordance with Austria), and Bourbon Spain; the Russian Empire later joined the newly-found alliance in 1726.[1] The signing of this treaty marks the founding of the Austro-Spanish Alliance and led the Fourth Anglo-Spanish War (1727-1729).[1] This new alliance thereby removed Austria from the Quadruple Alliance. In addition to a formation of the new partnership, the Habsburgs relinquished all formal claims to the Spanish throne, while the Spanish removed their claims in the Southern Netherlands, and a number of other territories.[1]

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

| Type | Peace, Defensive Alliance, Commerce |

| Context | Stately Quadrille |

| Signed | 5 November 1725 |

| Location | Vienna, Austria |

| Effective | 26 January 1726 |

| Expiry | 16 March 1731 (alliance only) |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Ratifiers | |

| Languages | Latin, Spanish, French |

Treaties on commerce between the two countries were also formally established.[1] The main article of importance is the Spanish recognition of the Ostend East India Company and the permission of free docking rights which included the rights to refuel in the Spanish colonies.[1] In addition, the treaty publicly signed certifying an alliance was only a defensive one, though later in the year, both parties signed a secret treaty which founded a general alliance between both nations.

Principle Conditions

Friendship between Spain and the Empire

Due to recent conclusion of the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1717-1720) and the earlier War of the Spanish Succession (1700-1714), and even though both of these wars had prior states of peace written, Austria and Spain both saw it necessary to make an established bilateral peace on matters that affected both nations personally.[2] In fact, this peace was directly modeled off the previous Treaty of London (1718) and the Treaty of The Hague (1720).[1]

"That there be a Christian, General, and perpetual Peace, and sincere Friendship between his Imperial and Catholic Majesty, and his Catholic Majesty the King of Spain their Heirs and Successors, hereditary Kingdoms, and the Subjects and Provinces thereof; the said Peace to be inviolably observed and cultivated..."[1]

Claim to the Kingdoms of Sardinia

Prior to the War of the Spanish Succession, the Kingdom of Sardinia had always been under the personal union to the King of Spain (and previously Aragon).[3] Though, in 1708, during the War of the Spanish Succession, the Austrians occupied Sardinia and the crown shifted to the ownership of Charles VI.[4] In 1720, the Kingdom was parceled out to Duke Victor Amadeus II of the House of Savoy, whereupon it was joined with the Savoyard lands to create the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont.[5] Charles VI agreed to officially abandon his claim to the Kingdom.[1]

"In the same Condition it was in when he made himself Master of it; and renounced, in favour of his Imperial Majesty, all Rights, Pretensions, Demands and Claims on the said Kingdom; so that his Imperial Majesty might fully and freely dispose of the same, as of his own Property, in such manner as he has done for the sake of the public Good."[1]

Recognition of the Peace of Utrecht

A principle agreement in the Peace of Utrecht was the newly seated Spanish Bourbons would be barred from ascending to the French throne; vice versa for the French Bourbons and the Spanish throne, thereby eliminating a possible personal union between France and Spain.[2] This agreement was simply reaffirmed, which denotes the seriousness of this matter.[1]

"In relation to the Right and Order of Succession to the Kingdoms of France and Spain; and renounces, as well for himself as for his Heirs, Descendants, and Successors, Male and Female, all Rights and Pretensions whatsoever in general, without any Exception, to any the Kingdoms, Territories and Provinces of the Spanish Monarchy, whereof the Catholic King was by the Treaty of Utrecht acknowledged lawful Possessor..."[1]

Habsburg renunciation of the Kingdom of Spain

Emperor Charles VI also relinquished all familial claims to the Kingdom of Spain, which allowed King Philip V to be considered the rightful claimant of the Spanish throne without dissent.[1] Charles was following in the actions of Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who had also waived his claims to the Spanish throne during the Peace of Utrecht ten years earlier.[1]

"By virtue of the said Renunciation, which his Imperial Majesty made for the sake of the general Safety of Europe, and in consideration that the Duke of Orleans had renounced, for himself and his Descendants, his Rights and Pretensions to the Kingdom of Spain, on Condition that neither the Emperor, nor any of his Descendants should ever succeed to the said Kingdoms; his Imperial and Catholic Majesty acknowledges King Philip V. for lawful King of Spain and the Indies; and will likewise let the said King of Spain', his Descendants, Heirs and Successors, Male and Female, peaceably enjoy all those Dominions of the Spanish Monarchy in Europe, in the Indies, and elsewhere, the Possession whereof was secured to him by the Treatys of Utrecht..."[1]

Spanish renunciation of the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily, similar to Sardinia, was a former Spanish possession, and was occupied by the Austrians during the War of the Spanish Succession; and in the Peace of Utrecht, the Kingdom was ceded to the Duke of Savoy.[5] Though, in 1717, during the War of the Quadruple Alliance, the Austrian's occupied Sicily once again. The only difference being that the Victor Amadeus II was an ally of the Empire, and had been invaded by the Spanish to be reacquired once again as a possession.

Therefore, the Austrian takeover of Sicily as a direct possession under Charles VI was debated as to whether the acquisition was legitimate or not. Regardless of Austrian legitimacy, Philip V renounced his personal and filial claims to the Kingdom of Sicily.[1]

"His Catholic Majesty renounces likewise all Rights of Reversion to the Kingdom of Sicily, which had been reserved to the Crown of Spain; and all other Claims and Pretensions..."[1]

Only ten years later, Sicily would again shift into Bourbon (not Spanish) hands. The Duke of Parma, Charles I d'Bourbon, would conquer Sicily from the Austrians in the War of the Polish Succession (1734-1735) and would be crowned the independent 'Charles V' as King of Sicily in 1735. Charles would later be crowned King of Spain as 'Charles III' in 1759, after the death of his brother Philip V. Though Charles was obligated to give up his Italian possessions to his son Ferdinand I.

Spanish renunciation of the Southern Netherlands

Prior to 1714, the Spanish had owned a portion of low-country territory which had become known as the Spanish Netherlands.[2] The Spanish had owned the territory starting with the abdication of Charles V (Charles I in Spain) as Holy Roman Emperor in 1556. Before Spanish ownership, it was occupied by the Austrians who conquered the provinces the War of the Burgundian Succession (1477-1482).

After the Austrians re-occupied the territory during the War of the Spanish Succession, it was decided at the Peace of Utrecht the lands of the Spanish Netherlands should pass once again to the Austrians.[2] Philip V agreed to a renunciation of his claims to the area in this article:

"And all other Claims and Pretensions, under Colour of which he might directly or indirectly disturb his Imperial Majesty, his Heirs and Successors, either in the above-mentioned Kingdoms and Provinces, or in any other Dominions which his Imperial Majesty actually possesses in the Netherlands and Italy, or any where else"[1]

Succession in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The final disputed territory was the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. Charles VI came to an agreement with Philip V that his heirs and siblings would have legal rights to Tuscany.[1] Grand Duke Gian de' Medici was ailing without issue and decided to be bedridden for the end of his reign.[6] Rights to the Duchies of Parma and Piacenza were also granted to the Spanish Bourbons.[1] The catch being these duchies would remain fiefs of the Holy Roman Empire, and not be independent of Imperial affairs.

"His Imperial Majesty, out of regard to the most serene Queen of Spain, has already consented, with a Reservation of the Consent of the Empire; and that being obtained, does again consent, that if, at any time, the Duchy of Tuscany, as also the Duchies of Parma and Piacenza, which are acknowledged by the contracting Parties in the Treaty of London to be undoubted Male Fiefs of the Empire, shall on failure of Male Issue ever happen to become vacant, and be open to the Disposal of the Emperor and Empire"[1]

Spanish concessions in Livorno and Elba

King Philip V agreed to establish the City of Livorno as a free port of entry for both parties.[1] The Tuscan Isle of Elba and the Town of Porto Logone were agreed to be ceded to the future claimant and owner of the throne of Tuscany upon their accession.[1] In addition to these concessions, Philip V was obligated to rescind his claims on these duchies.

"The Catholic King does, moreover, promise and oblige himself to yield and deliver up the Town of Porto Longone, together with that part of the Island of Elba which he possesses, to the aforesaid Prince, his and the Queen's Son, as soon as he shall, in due Time and Order, attain the actual Possession of the Dukedom of Tuscany. And he renounces for himself and his Successors, Kings of Spain, ail Rights of claiming, acquiring, or ever possessing any Thing in the said Duchies..."[1]

%252C_Holy_Roman_Emperor.jpg.webp)

Spanish recognition of the Pragmatic Sanction

An important victory for Charles VI was Philip V's acceptance of Charles' Pragmatic Sanction of 1713. While Charles agreed to withdraw his claims to the Spanish throne and consented to defend the Spanish succession, Philip agreed to the Austrian Succession.[1] The Spanish recognition of the Sanction would continue Charles VI's lifelong pursuit to secure his daughter Maria Theresa's succession to the Austrian throne and approval in an Imperial Election.

"His Imperial Majesty further promises, that he will defend and guaranty, and, as often as there shall be occasion, maintain the Order of Succession settled in the Kingdom of Spain...the King of Spain promises likewise to defend and guaranty that Order of Succession, which his Imperial Majesty, according to the Intention of his Ancestors, has declared and established in his most serene House...and has been cheerfully and dutifully acknowledged and entered among the public Acts, to have the Force of a Law and Pra2gmatic Sanction of perpetual Validity."[1]

Commerce Provision

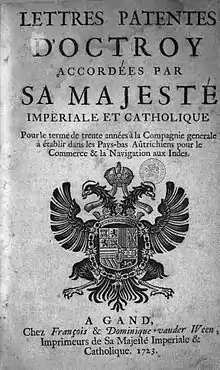

Ostend East India Company

The main commerce clause within the treaty was the recognition of the Ostend East India Company. Philip V granted the Company permission to dock and resupply in Spanish dominions and states across the globe, providing these ships produce proper documentation.[1] The Ostend Company was granted the same privileges granted to the United Provinces in matters of trade.

"It shaII be allowed to bis Imperial Majesty's Subjects and Ships to carry and import from the East-lndies, into any of the King of Spain; States and Dominions, all forts of Fruits, Things, and Merchandises: provided it appear from the Certificates of the deputies of the India Company, erected in the Austrian Low Countries, that they are the 'Produce of the 'Places conquered, the Colonies, or the Factories of the said Company, or that they came from thence; and in this Respect they shall enjoy the fame Privileges that were granted to the Subjects of the United Provinces..."[1]

Austro-Spanish alliance

The last of the three separate treaties written in Vienna was the defensive military alliance between the Habsburgs and Spain. After Spain's severe loss in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1717-1720) and weakening in the War of the Spanish Succession (1700-1714) the balance of power needed to be reset in Europe; and the Habsburgs believed making peace and fostering a new relationship with the Spanish would spark a realignment of control.[1] Both army and naval support were guaranteed in the event of either nation being attacked by a foreign power.

"That there be and remain a solid and sincere Friendship betwixt his Imperial Catholic Majesty and his Royal Catholic Majesty and that the fame be so cultivated on both sides, that the one shall promote the Advantages and avert the Injuries of the other as much as their own."[1]

Restitution of Gibraltar and Menorca

A principle condition on the formation of the alliance was the Spanish claims in Gibraltar and Menorca. These territories were annexed by the British during the War of the Spanish Succession, and Spain began quickly scheming on how to reacquire them. Habsburg support for the restitution was not military but financial; and promoted itself as a mediator for the peace succeeding the future war.[1]

"And whereas it has been represented by the Minister of the most Serene King of Spain, that the Restitution of Gibraltar.....his Sacred Imperial and Catholic Majesty, that he will not oppose the said Restitution, if it be effected in an amicable manner; and that if it be thought necessary, he will make use of all good Offices for that purpose, and if the Party's desire it, he will also act in the Affair as Mediator.[1]

References

- Knapton, J.J. & P. (1732). A General Collection of Treaties of Peace and Commerce, Manifestos, Declarations of War, and other Publick Papers, from the End of the Reign of Queen Anne to the Year 1731. University of Toronto. pp 457-485

- James Falkner (2015). The War of the Spanish Succession 1701-1714. Pen and Sword. p. 205.

- Geronimo Zurita, Los cinco libros postreros de la segunda parte de los Anales de la Corona d'Aragon, Oficino de Domingo de Portonaris y Ursono, Zaragoza, 1629, libro XVII, pag. 75–76

- McKay, Derek. "Bolingbroke, Oxford and the Defence of the Utrecht Settlement in Southern Europe". The English Historical Review,. 86:339 (1971), 264–84.

- Symcox, Geoffrey (1983). Victor Amadeus II: absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675-1730. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04974-1.

- Acton, Harold (1980). The Last Medici. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-29315-0.