War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) was an early 18th century European war, triggered by the death in November 1700 of the childless Charles II of Spain. It established the principle that dynastic rights were secondary to maintaining the balance of power between different countries.[1] Related conflicts include the 1700–1721 Great Northern War, Rákóczi's War of Independence in Hungary, the Camisard revolt in southern France, Queen Anne's War in North America and minor struggles in Colonial India.

| War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Philip accepts the Spanish throne as Philip V; November 16, 1700 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Although weakened by over a century of continuous conflict, in 1700 the Spanish Empire remained a global confederation that included the Spanish Netherlands, large parts of Italy, the Philippines and much of the Americas. Charles's closest heirs were members of the Austrian Habsburgs or French Bourbons; acquisition of an undivided Spanish Empire by either threatened the European balance of power.

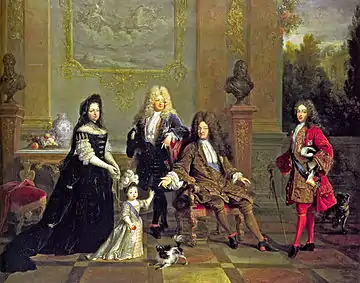

Attempts by Louis XIV of France and William III of England to partition the empire in 1698 and 1700 were rejected by the Spanish. Instead, Charles named Philip of Anjou, a grandson of Louis XIV, as his heir; if he refused, the alternative was Charles, younger son of Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor. Philip accepted and was proclaimed king of an undivided Spanish Empire on 16 November 1700, leading to war between France and Spain on one side, and the Grand Alliance on the other.

The French held the advantage in the early stages, but were forced onto the defensive after 1706; however, by 1710 the Allies had failed to make any significant progress, while Bourbon victories in Spain had secured Philip's position as king. When Emperor Joseph I died in 1711, Charles succeeded his brother as emperor, and the new British government initiated peace talks. Since only British subsidies kept their allies in the war, this resulted in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, followed by the 1714 Treaties of Rastatt and Baden.

Philip was confirmed as king of Spain in return for accepting its permanent separation from France; the Spanish Empire remained largely intact, but ceded territories in Italy and the Low Countries to Austria and Savoy. Britain retained Gibraltar and Menorca which it captured during the war, acquired significant trade concessions in the Spanish Americas, and replaced the Dutch as the leading maritime and commercial European power. The Dutch gained a strengthened defence line in what was now the Austrian Netherlands; although they remained a major commercial power, the cost of the war permanently damaged their economy.

France withdrew backing for the exiled Jacobites and recognised the Hanoverians as heirs to the British throne; ensuring a friendly Spain was a major achievement, but left them financially exhausted. The decentralisation of the Holy Roman Empire continued, with Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony increasingly acting as independent states. Combined with victories over the Ottomans, this meant the Austrian Habsburgs increasingly switched their focus to southern Europe.

Background

In 1665 Charles II became the King of Spain; suffering from ill-health all his life, his death was anticipated almost from birth, and his successor a matter of diplomatic debate for decades. In 1670, England agreed to support the rights of Louis XIV to the Spanish throne in the Treaty of Dover, while the terms of the 1688 Grand Alliance committed England and the Dutch Republic to back Leopold.[2]

In 1700, the Spanish Empire included possessions in Italy, the Spanish Netherlands, the Philippines and the Americas, and though no longer the dominant great power, it remained largely intact.[3] Its acquisition by either the Austrian Habsburgs or French Bourbons would change the balance of power in Europe, and so its inheritance led to a war that involved most of the European powers. The 1700–1721 Great Northern War is considered a connected conflict, for it impacted the involvement of states such as Sweden, Saxony, Denmark–Norway and Russia.[4]

During the 1688–1697 Nine Years' War, armies grew from an average of 25,000 in 1648 to over 100,000 by 1697, a level unsustainable for pre-industrial economies.[5] The 1690s also marked the lowest point of the Little Ice Age, a period of colder and wetter weather that drastically reduced crop yields across Europe.[6] It is estimated the Great Famine of 1695–1697 killed 15–25% of the population in present-day Scotland, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Norway, and Sweden, plus another two million in France and Northern Italy.[7]

The 1697 Treaty of Ryswick was the result of mutual exhaustion and acceptance by Louis that France could not achieve its objectives without allies. Given that it left the Succession unresolved, Leopold signed with extreme reluctance in October 1697; and with Charles's health now clearly failing, it was seen only as a pause in hostilities.[8]

Partition treaties

Unlike France or Austria, the Spanish crown could be inherited through the female line. This allowed Charles' sisters Maria Theresa (1638–1683) and Margaret Theresa (1651–1673) to pass their rights onto the children of their respective marriages with Louis XIV and Emperor Leopold. Louis sought to avoid conflict over the issue through direct negotiation with his main opponent William III of England, while excluding the Spanish.[9]

Maria Antonia (1669–1692), daughter of Leopold and Margaret, married Maximillian Emanuel of Bavaria in 1685, and on 28 October 1692, they had a son, Joseph Ferdinand. Under the October 1698 Treaty of the Hague between France, Britain and the Dutch Republic, five-year old Joseph was designated heir to Charles II; in return, France and Austria would receive parts of Spain's European territories.[10] Charles refused to accept this; on 14 November 1698, he published a will leaving an undivided Spanish monarchy to Joseph Ferdinand. However, the latter's death from smallpox in February 1699 undid these arrangements.[11]

In 1685, Maria Antonia passed her claim to the Spanish throne onto Leopold's sons, Joseph and Archduke Charles.[12] Her right to do so was doubtful, but Louis and William used this to devise the 1700 Treaty of London. Archduke Charles became the new heir, while France, Savoy and Austria received territorial compensation; however, since neither Leopold or Charles agreed, the treaty was largely pointless.[13] By early October 1700, Charles was clearly dying; his final will left the throne to Louis XIV's grandson Philip, Duke of Anjou; if he refused, the offer would pass to his younger brother the Duke of Berry, followed by Archduke Charles.[14]

Charles died on 1 November 1700, and on the 9th, Spanish ambassadors formally offered the throne to Philip. Louis briefly considered refusing; although it meant the succession of Archduke Charles, insisting William help him enforce the Treaty of London meant he might achieve his territorial aims without fighting. However, his son the Dauphin rejected the idea; French diplomats also advised Austria would fight regardless, while neither the British or Dutch would go to war for a settlement intended to avoid war. Louis therefore accepted on behalf of his grandson, who was proclaimed Philip V of Spain on 16 November 1700.[14]

Prelude to war

.png.webp)

With most of his objectives achieved by diplomacy, Louis now made a series of moves that combined to make war inevitable.[15] The Tory majority in the English Parliament objected to the Partition Treaties, chiefly the French acquisition of Sicily, an important link in the lucrative Levant trade.[16] However, a foreign diplomat observed their refusal to become involved in a European war was true 'only so long as English commerce does not suffer.'[17] Louis either failed to appreciate this or decided to ignore it and his actions gradually eroded Tory opposition.[18]

In early 1701, Louis registered Philip's claim to the French throne with the Paris Parlement, raising the possibility of union with Spain, contrary to Charles' will. In February, the Spanish-controlled Duchies of Milan and Mantua in Northern Italy announced their support for Philip and accepted French troops. Combined with efforts to build an alliance between France and Imperial German states in Swabia and Franconia, these were challenges Leopold could not ignore.[19]

Helped by the Viceroy, Max Emanuel of Bavaria, French troops replaced Dutch garrisons in the 'Barrier' fortresses in the Spanish Netherlands, granted at Ryswick. It also threatened the monopoly over the Scheldt granted by the 1648 Peace of Münster, while French control of Antwerp and Ostend would allow them to blockade the English Channel at will.[20] Combined with other French actions that threatened English trade, this produced a clear majority for war and in May 1701, Parliament urged William to negotiate an anti-French alliance.[21]

On 7 September, Leopold, the Dutch Republic and Britain[lower-alpha 1] signed the Treaty of The Hague renewing the 1689 Grand Alliance. Its provisions included securing the Dutch Barrier in the Spanish Netherlands, the Protestant succession in England and Scotland and an independent Spain but did not refer to placing Archduke Charles on the Spanish throne.[22] When the exiled James II of England died on 16 September 1701, Louis reneged on his recognition of the Protestant William III as king of England and Scotland and supported the claim of his son, James Francis Edward Stuart. War became inevitable and when William himself died in March 1702, his successor Queen Anne confirmed her support for the Treaty of the Hague. The Dutch did the same and on 15 May the Grand Alliance declared war on France, followed by the Imperial Diet on 30 September.[23]

General strategic drivers

The importance of trade and economic interests to the participants is often underestimated; contemporaries viewed Dutch and English support for the Habsburg cause as primarily driven by a desire for access to the American markets.[24] Modern economists generally assume a constantly growing market, but the then-dominant theory of Mercantilism viewed it as relatively static. Increasing your share implied taking it from someone else, the government's role is to restrict foreign competition by attacking merchant ships and colonies.[25]

That expanded the war to North America, India, and other parts of Asia, with tariffs used as a policy weapon. From 1690 to 1704, English import duties on foreign goods increased by 400%, and the 1651–1663 Navigation Acts were a major factor in the Anglo-Dutch Wars. On 6 September 1700, France banned the import of English manufactured goods like cloth and imposed prohibitive duties on a wide range of others.[26]

Armies of the Nine Years' War often exceeded 100,000 men, levels unsustainable for pre-industrial economies; those of 1701–1714 averaged around 35,000 to 50,000.[27] Dependence on water-borne transport for supplying these numbers meant campaigns were focused on rivers like the Rhine or Adda, which limited operations in poor areas like Northern Spain. Better logistics, unified command, and simpler internal lines of communication gave Bourbon armies an advantage over their opponents.[28]

Specific objectives

Britain (England and Scotland pre-1707)

Alignment on reducing the power of France and securing the Protestant succession for the British throne masked differences on how to achieve them. In general, the Tories favoured a mercantilist strategy of using the Royal Navy to attack French and Spanish trade while protecting and expanding their own; land commitments were viewed as expensive and primarily of benefit to others.[29] The Whigs argued France could not be defeated by seapower alone, making a Continental strategy essential, while Britain's financial strength made it the only member of the Alliance able to operate on all fronts against France.[30]

Dutch Republic

Although Marlborough was Allied commander in the Low Countries, the Dutch provided much of the manpower, and strategy in this theatre was subject to their approval. The 1672 to 1678 Franco-Dutch War showed the Spanish could not defend the Southern Netherlands, and so the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick allowed the Dutch to place garrisons in eight key cities. They hoped this barrier would provide the strategic depth needed to protect their commercial and demographic heartlands around Amsterdam against attack from the south. In the event, they were quickly over-run in 1701, then later in 1748, and modern historians consider the idea fundamentally flawed. However, Dutch priorities were to re-establish and strengthen the Barrier fortresses, retain control of the economically vital Scheldt estuary, and gain access to trade in the Spanish Empire.[31]

Austria / Holy Roman Empire

Despite being the dominant power within the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian and Imperial interests did not always coincide. The Habsburgs wanted to put Archduke Charles on the throne of an undivided Spanish Monarchy, while their Allies were fighting to prevent either the Bourbons or the Habsburgs from doing so. This divergence and Austria's financial collapse in 1703 meant the campaign in Spain was reliant on Anglo-Dutch naval support and after 1706, British funding. Particularly during the reign of Joseph I, the priority for the Habsburgs was to secure their southern borders from French intervention in northern Italy and suppress Rákóczi's War of Independence in Hungary.[32]

Much of the Spanish nobility resented what they considered to be the arrogance of the Austrians, a key factor in the selection of Philip as their preferred candidate in 1700. In return for British support, Charles agreed to major commercial concessions within the Empire, as well as accepting British control of Gibraltar and Menorca. These made him widely unpopular at all levels of Spanish society, and he was never able to sustain himself outside the coastal regions, which could be supplied by the Royal Navy. [33]

The Wittelsbach-controlled states of Bavaria, Liège, Cologne allied with France, but the vast majority of the Empire remained neutral, or limited their involvement to the supply of mercenaries. Like Bavaria, the larger entities pursued their own policies; his claim to the Polish crown meant Augustus of Saxony focused on the Great Northern War, while Frederick I made his support dependent on Leopold recognising Prussia as a kingdom and making it an equal member of the Grand Alliance. Since George, Elector Hanover was also heir to the British throne, his support was more reliable, but the suspicion remained the interests of Hanover came first.[34]

France

Under Louis XIV, France was the most powerful state in Europe with revenue-generating capacities that far exceeded its rivals. Its geographical position provided enormous tactical flexibility; unlike Austria, it had its navy, and as the campaigns of 1708–1710 proved, even under severe pressure it could defend its borders. The Nine Years' War had shown France could not impose its objectives without support but the alliance with Spain and Bavaria made a successful outcome far more likely. Apart from denying an undivided Spanish Monarchy to others, Louis's objectives were to secure his borders with the Holy Roman Empire, weaken Austria and increase French commercial strength through access to the trade of the Americas.

.png.webp)

Spain

Although Spain remained a great power, almost constant warfare during the 17th century made the economy subject to long periods of low productivity and depression. Enacting political or economic reform was extremely complex since Habsburg Spain was a personal union between the Crowns of Castile and Aragon, each with very different political cultures.[lower-alpha 2] Most of Philip's support came from the Castilian elite.[35]

Savoy

During the Nine Years' War, Savoy joined the Grand Alliance in 1690 before agreeing on a separate peace with France in 1696. The Duchy was strategically important as it provided access to the southern borders of Austria and France. Philip's accession as King of Spain in 1701 placed Savoy between the Spanish-ruled Duchy of Milan and France, while the Savoyard County of Nice and County of Savoy were in Transalpine France, and thus very difficult to defend.[36]

Victor Amadeus II allied with France in 1701 but his long-term goal was the acquisition of Milan; neither France, Austria, or Spain would relinquish this voluntarily, leaving Britain as the only power that could. After the Royal Navy established control over the Western Mediterranean in 1703, Savoy changed sides. During 1704, the French captured Villefranche and the County of Savoy, accompanied by an offensive in Piedmont; by the end of 1705, Victor Amadeus controlled only his capital of Turin.[37]

Military campaigns 1701–1708

Italy

The war in Italy primarily involved the Spanish-ruled Duchies of Milan and Mantua, considered essential to the security of Austria's southern borders. In 1701, French troops occupied both cities and Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy, allied with France, his daughter Maria Luisa marrying Philip V.[38] In May 1701, an Imperial army under Prince Eugene of Savoy moved into Northern Italy; by February 1702, victories at Carpi, Chiari and Cremona forced the French behind the Adda river.[39]

Vendôme, one of the best French generals, took command and was substantially reinforced; Prince Eugene managed a draw at the Battle of Luzzara but the French recovered most of the territory lost the year before.[40] In October 1703, Victor Amadeus declared war on France; by May 1706, the French held most of Savoy except Turin while victories at Cassano and Calcinato forced the Imperialists into the Trentino valley.[41]

However, in July 1706 Vendôme and any available forces were sent to reinforce France's northern frontier after the defeat at Ramillies. Reinforced by German auxiliaries, Prince Eugene broke the Siege of Turin in September; despite a minor French victory at Castiglione, the war in Italy was over. To the fury of his allies, in the March 1707 Convention of Milan Emperor Joseph gave French troops in Lombardy free passage to Southern France.[42]

A combined Savoyard-Imperial attack on the French base of Toulon planned for April was postponed when Imperial troops were diverted to seize the Spanish Bourbon Kingdom of Naples. By the time they besieged Toulon in August, the French were too strong, and they were forced to withdraw. By the end of 1707, fighting in Italy ceased, apart from small-scale attempts by Victor Amadeus to recover Nice and Savoy.[43]

Low Countries, Rhine and Danube

The first objective for the Grand Alliance in this theatre was to secure the Dutch frontiers, threatened by the alliance between France, Bavaria, and Joseph Clemens of Bavaria, ruler of Liège and Cologne. During 1702, the Barrier fortresses were retaken along with Kaiserswerth, Venlo, Roermond and Liège.[44] The 1703 campaign was marred by Allied conflicts over strategy; they failed to take Antwerp, while the Dutch defeat at Ekeren in June led to bitter recriminations.[45]

On the Upper Rhine, Imperial forces under Louis of Baden remained on the defensive, although they took Landau in 1702. Throughout 1703, French victories at Friedlingen, Höchstädt and Speyerbach with the capture of Kehl, Breisach and Landau directly threatened Vienna.

In 1704, Franco-Bavarian forces continued their advance with the Austrians struggling to suppress Rákóczi's revolt in Hungary.[46] To relieve the pressure, Marlborough marched up the Rhine, joined forces with Louis of Baden and Prince Eugene, and crossed the Danube on 2 July. Allied victory at Blenheim on 13 August forced Bavaria out of the war and the Treaty of Ilbersheim placed it under Austrian rule.[47]

Allied efforts to exploit their victory in 1705 foundered on poor co-ordination, tactical disputes and command rivalries, while Leopold's ruthless rule in Bavaria caused a brief but vicious peasant revolt.[48] In May 1706, an Allied force under Marlborough shattered a French army at the Battle of Ramillies and the Spanish Netherlands fell to the Allies in under two weeks.[49] France assumed a defensive posture for the rest of the war; despite the loss of strongpoints like Lille, they prevented the Allies from making a decisive breach in their frontiers. By 1712, the overall position remained largely unchanged from 1706.[50]

Spain and Portugal

British involvement was driven by safeguarding their trade routes in the Mediterranean, while by putting Archduke Charles on the Spanish throne, they hoped to gain commercial privileges within the Spanish Empire. The Habsburgs viewed Northern Italy and suppressing the Hungarian revolt as higher priorities, while after 1704 the Dutch focused on Flanders. As a result, this theatre was largely dependent on British naval and military support; high casualties from disease made it a heavy drain on resources, for little apparent benefit.[51]

Spain was a union between the Crowns of Castile and Aragon, which was divided into the Principality of Catalonia, plus the Kingdoms of Aragon, Valencia, Majorca, Sicily, Naples and Sardinia. In 1701, Majorca, Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia declared for Philip, while a mixture of anti-Castilian and anti-French sentiment meant the others supported Archduke Charles, the most important being Catalonia. Allied victory at Vigo Bay in October 1702 persuaded Peter II of Portugal to switch sides, giving them an operational base in this area.[52]

Archduke Charles landed at Lisbon in March 1704 to begin a land campaign, while the British capture of Gibraltar was a significant blow to Bourbon prestige. An attempt to retake it was defeated at in August, with a land siege being abandoned in April 1705.[53] The 1705 'Pact of Genoa' between Catalan representatives and Britain opened a second front in the north-east; the loss of Barcelona and Valencia left Toulon as the only major port available to the Bourbons in the Western Mediterranean. Philip tried to retake Barcelona in May 1706 but was repulsed, while his absence allowed an Allied force from Portugal to enter Madrid and Zaragossa.[54]

However, lack of popular support and logistical issues meant the Allies could not hold territory away from the coastline, and by November, Philip controlled Castile, Murcia, and parts of Valencia. Allied efforts to regain the initiative ended with defeat at Almansa in April 1707, followed by failure to take Toulon in August. The capture of Menorca in 1708, combined with possession of Gibraltar, gave the British control of the Western Mediterranean, which many considered their primary objective.[51]

War beyond Europe and related conflicts

The close links between war and trade meant conflict extended beyond Europe, particularly in North America, where it is known as Queen Anne's War, and the West Indies, which produced sugar, then hugely profitable. Also, there were minor trade conflicts in South America, India, and Asia; the financial strains of war particularly affected the Dutch East India Company, as it was a huge drain on scarce naval resources.

Related conflicts include Rákóczi's War of Independence in Hungary, which was funded by France and a serious concern for the Habsburgs throughout the war. In South-Eastern France, Britain funded the Huguenot 1704–1710 Camisard rebellion; one objective of the 1707 campaign in Northern Italy and Southern France was to support this revolt, one of a series that began in the 1620s.

No peace without Spain; 1709–1713

By the end of 1708, the French had withdrawn from Northern Italy, while the Maritime Powers controlled the Spanish Netherlands, and secured the borders of the Dutch Republic; in the Mediterranean, Britain's Royal Navy had achieved naval supremacy, and acquired permanent bases in Gibraltar and Menorca. However, as Marlborough himself pointed out, the French frontiers remained largely intact, their army showed no signs of being defeated, while Philip proved far more popular with the Spanish than his rival. Many of the objectives set out by the Grand Alliance in 1701 had been achieved, but success in 1708 made them overconfident.[55]

Diplomacy

France viewed the Dutch as the most likely to favour a quick end to the war; Ramillies removed any direct military threat to the Republic, while highlighting differences with Britain on the Spanish Netherlands. Initial peace talks broke down since the Allies had agreed to negotiate jointly, but could not agree terms.[56] After the severe winter of 1708 caused widespread famine in France and Spain, Louis reopened talks, and in May 1709, the Allies presented him with the 'Preliminaries of Hague'. Philip was given two months to cede his throne to Archduke Charles, while France was required to remove him by force if he did not comply.[57]

The terms seriously underestimated France's ability to continue the war, assumed Philip would abdicate on request, and required the Spanish to accept Archduke Charles as king, which they were clearly unwilling to do.[58] While Louis was willing to abandon his ambitions in Spain, making war on his grandson was unacceptable; when publicicised, the terms were considered so offensive they ended by strengthening French resolve to fight on.[59]

Marlborough's 1709 offensive in Northern France led to the Battle of Malplaquet on 11 September, between an Allied army of 86,000 and a French one of 75,000. Technically an Allied victory, it cost them 20,000 men; these enormous casualties increased war-weariness in Britain and the Dutch Republic, and showed the fighting ability of the French army remained intact. This was compounded by Spanish victories at Alicante in April, and La Gudina in May.[60]

The Dutch now discovered they had been excluded from a commercial agreement between Britain and Archduke Charles, awarding them trading rights in Spanish America. This deepened divisions between the Allies, while increasing Spanish opposition to having Charles as their king. The Whig government tried to compensate the Dutch by concessions in the Spanish Netherlands, which were opposed by the Tories as detrimental to British commerce.[60]

The Whigs had won the 1708 British general election by arguing military victory was the quickest road to peace, but failure in France was mirrored in Spain. Archduke Charles re-entered Madrid in 1710 after victories in the Battle of Almenar and Battle of Saragossa, but the Allies could not hold the interior and were forced to retreat. 3,500 British troops surrendered at the Brihuega on 8 December, and the Battle of Villaviciosa on 10 December confirmed Bourbon control of Spain.[61]

Negotiations

When negotiations resumed in March 1710 at Geertruidenberg, it was clear to the French the mood in Britain had changed. This was confirmed when the pro-peace Tories won a landslide victory in the October 1710 British general election, although they confirmed their commitment to the war to prevent a credit crisis. Despite the capture of Bouchain in September, a decisive victory in Northern France continued to elude the Allies, and an expedition against Quebec in French North America ended in disaster.[62]

When Emperor Joseph died in April 1711, Archduke Charles was elected Emperor; continuing the war now seemed pointless since the union of Spain with Austria was as unwelcome as one with France. The British secretly negotiated peace terms directly with France, leading to the signing of the Preliminary Articles of London on 8 October 1711.[lower-alpha 3] They included French acceptance of the Act of Settlement and a guarantee the French and Spanish crowns would remain separate; France undertook to ensure Spain ceded Gibraltar and Menorca and award the Asiento to Britain for 30 years.[63]

Despite resentment at their exclusion from the Anglo-French negotiations, the Dutch were financially exhausted by the enormous cost of the war, and could not continue without British support. Although Charles VI initially rejected the idea of a peace conference, he reluctantly agreed once the Dutch decided to support it, but Habsburg opposition to the treaty continued.[64]

Peace of Utrecht

Within weeks of the conference opening, events threatened the basis of the peace agreed between Britain and France. First, the French presented proposals awarding the Spanish Netherlands to Max Emmanuel of Bavaria and a minimal Barrier, leaving the Dutch with little to show for their huge investment of money and men. Second, a series of deaths left Louis XIV's two-year-old great-grandson, the future Louis XV as heir, making Philip next in line and his immediate renunciation imperative.[65]

The Dutch and Austrians fought on, hoping to improve their negotiating position but Bolingbroke issued 'Restraining Orders' to Marlborough's replacement, the Duke of Ormonde, instructing him not to participate in offensive operations against the French.[66] These orders caused fury then and later, with Whigs urging Hanoverian military intervention; those George considered responsible, including Ormonde and Bolingbroke were driven into exile after his succession, and became prominent Jacobites.[67]

Prince Eugene captured Le Quesnoy in June and besieged Landrecies but was defeated at Denain on 24 July; the French went on to recapture Le Quesnoy and many towns lost in previous years, including Marchines, Douai, and Bouchain. This showed the French retained their fighting ability, while the Dutch finally reached the end of their willingness and ability to continue the war.[68]

On 6 June, Philip confirmed his renunciation of the French throne, and the British offered the Dutch a revised Barrier Treaty, replacing that of 1709 which they rejected as overly generous. A significant improvement on the 1697 Barrier, it was subject to Austrian approval; although the final terms were less beneficial, it was sufficient for the Dutch to agree peace terms.[69]

Charles withdrew from the Conference when France insisted he guarantee not to acquire Mantua or Mirandola; he was supported in this by George, Elector of Hanover, who wanted France to withdraw support for the Stuart heir James Francis. As a result, neither Austria nor the Empire signed the Treaty of Utrecht of 11 April 1713 between France and the other Allies; Spain made peace with the Dutch in June, then Savoy and Britain on 13 July 1713.[70]

Treaties of Rastatt and Baden

Fighting continued on the Rhine, but Austria was financially exhausted, and after the loss of Landau and Freiburg in November 1713, Charles came to terms. The Treaty of Rastatt on 7 March 1714 confirmed Austrian gains in Italy, returned Breisach, Kehl, and Freiburg, ended French support for the Hungarian revolt and agreed on terms for the Dutch Barrier fortresses. Charles abandoned his claim to Strasbourg and Alsace and agreed to the restoration of the Wittelsbach Electors of Bavaria and Cologne, Max Emmanuel, and Joseph Clemens. Article XIX of the treaty transferred sovereignty over the Spanish Netherlands to Austria.[71]

On 7 September, the Holy Roman Empire joined the agreement by the Treaty of Baden; although Catalonia and Majorca were not finally subdued by the Bourbons until June 1715, the war was over.

Aftermath

Article II of the Peace of Utrecht included the stipulation "because of the great danger which threatened the liberty and safety of all Europe, from the too-close conjunction of the kingdoms of Spain and France,... the same person should never become King of both kingdoms." Some historians view this as a key point in the evolution of the modern nation-state; Randall Lesaffer argues it marks a significant milestone in the concept of collective security.[72]

Britain is usually seen as the main beneficiary of Utrecht, which marked its rise to becoming the dominant European commercial power.[73] It established naval superiority over its competitors, acquired the strategic Mediterranean ports of Gibraltar and Menorca and trading rights in Spanish America. France accepted the Protestant succession, ensuring a smooth inheritance by George I in August 1714, while agreeing to end support for the Stuarts in the 1716 Anglo-French Treaty.[74] Although the war left all participants with unprecedented levels of government debt, only Britain was able to finance it efficiently, providing a relative advantage over its competitors.[75]

Philip was confirmed as King of Spain, which retained its independence and the majority of its empire, in return for ceding the Spanish Netherlands, most of their Italian possessions, as well as Gibraltar and Menorca. These losses were deeply felt; Naples and Sicily were regained in 1735 and Menorca in 1782, although Gibraltar is still held by Britain, despite numerous attempts to regain it. The 1707 Nueva Planta decrees centralised power in Madrid, and abolished regional political structures, although Catalonia and Majorca remained outside the system until 1767.[76] Their economy recovered remarkably quickly, while the Bourbon dynasty remains the reigning royal house in Kingdom of Spain.[77]

Despite failure in Spain, Austria secured its position in Italy and Hungary and acquired the bulk of the Spanish Netherlands; even after reimbursing the Dutch for the cost of their Barrier garrisons, the increased revenues funded a significant expansion of the Austrian army.[78] The shift of Habsburg focus away from Germany and into Southern Europe continued with victory in the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–18. Their position as the dominant power within the Holy Roman Empire was challenged by Bavaria, Hanover, Prussia, and Saxony, who increasingly acted as independent powers; in 1742, Charles of Bavaria became the first non-Habsburg Emperor in over 300 years.[79]

The Dutch Republic ended the war effectively bankrupt, while the barrier that cost so much proved largely illusory.[80] The forts were quickly overrun in 1740, with Britain's promise of military support against an aggressor proving far more effective.[81] The economy was permanently affected by the damage inflicted by the war on their merchant navy, and while retaining their position in the Far East, Britain replaced them as the pre-eminent commercial and maritime power.[82]

Louis XIV died on 1 September 1715, his five-year-old great-grandson reigning as Louis XV until 1774; on his deathbed, he is alleged to have admitted, "I have loved war too well".[83] True or not, while the final settlement was far more favourable than the Allied terms of 1709, it is hard to see what Louis gained that he had not already achieved through diplomacy by February 1701.[84]

Since 1666, Louis had based his policies on the assumption of French military and economic superiority over their rivals; by 1714, this was no longer the case. Concern over the expansion of British trade post-Utrecht, and the advantage provided over its rivals, was viewed by his successors as a threat to the balance of power, and a major factor behind French participation in the 1740 to 1748 War of the Austrian Succession.[85]

Wider implications include the rise of Prussia and Savoy while many of the participants were involved in the 1700–1721 Great Northern War, with Russia becoming a major European power for the first time as a result. Finally, while colonial conflicts were relatively minor and largely confined to the North American theatre, the so-called Queen Anne's War, they were to become a key element in future wars.[84] Meanwhile, maritime unemployment brought on by the war's end led to the third stage of the Golden Age of Piracy, as many sailors formerly employed in the navies of the warring powers turned to piracy for survival.[86]

See also

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnotes

- England and Scotland were separate kingdoms until 1707 but the Treaty was signed by William as King of Great Britain

- Aragon was divided into the Kingdoms of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Majorca, Naples, Sicily, Malta, and Sardinia.

- Also known as the Mesnager Convention.

References

- Falkner 2015, p. 7.

- Hochedlinger 2003, p. 171.

- Storrs 2006, pp. 6–7.

- Frey 1995, pp. 191–192.

- Childs 1991, p. 1.

- White 2011, pp. 542–543.

- de Vries 2009, pp. 151–194.

- Meerts 2014, p. 168.

- Frey 1995, p. 389.

- McKay & Scott 1983, pp. 54–55.

- Ward & Leathes 1912, p. 385.

- Ingrao 2000, p. 105.

- Kamen 2001, p. 3.

- Rule 2017, pp. 91–108.

- Falkner 2015, pp. 508–510.

- Gregg 1980, p. 126.

- Somerset 2012, p. 166.

- Falkner 2015, p. 96.

- Thompson 1973, pp. 158–160.

- Israel 1989, pp. 197–199.

- Somerset 2012, p. 167.

- Somerset 2012, p. 168.

- Wolf 1974, p. 514.

- Schmidt Voges & Solana Crespo 2017, p. 2.

- Rothbard 2010.

- Schaeper 1986, p. 1.

- Childs 1991, p. 2.

- Falkner 2015, p. 37.

- Shinsuke 2013, pp. 37–40.

- Ostwald 2014, pp. 100–129.

- Lesaffer.

- Ingrao 1979, p. 220.

- Hattendorf 1979, pp. 50–54.

- Ingrao 1979, pp. 39–40.

- Cowans 2003, pp. 26–27.

- Symcox 1983, p. 147.

- Symcox 1983, p. 149.

- Dhondt 2015, pp. 16–17.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 270–271.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 276–277.

- Falkner 2015, p. 1302.

- Sundstrom 1992, p. 196.

- Symcox 1985, p. 155.

- Lynn 1999, p. 275.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 280–281.

- Ingrao 1979, p. 123.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 286–294.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 298–299.

- Holmes 2008, pp. 347–349.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 320–323.

- Atkinson 1944, pp. 233–233.

- Francis 1965, pp. 71–93.

- Lynn 1999, p. 296.

- Lynn 1999, p. 302.

- Nicholson 1955, pp. 124–125.

- Bromley 1979, p. 446.

- Ward & Leathes 1912, pp. 422–423.

- Kamen 2001, pp. 70–72.

- Ward & Leathes 1912, p. 424.

- Gregg 1980, p. 289.

- Kamen 2001, p. 101.

- Simms 2008, pp. 60–64.

- Bromley 1979, pp. 459–460.

- Dadson 2014, p. 63.

- Somerset 2012, p. 470.

- Gregg 1980, p. 354.

- Somerset 2012, p. 477.

- Holmes 2008, p. 462.

- Myers 1917, pp. 799–829.

- Somerset 2012, pp. 494–495.

- Frey 1995, pp. 374–375.

- Lesaffer 2014.

- Pincus & Warwick, pp. 7–8.

- Szechi 1994, pp. 93–95.

- Carlos, Neal & Wandschneider 2006, p. 2.

- Vives 1969, p. 591.

- Fernández-Xesta y Vázquez 2012.

- Falkner 2015, pp. 4173–4181.

- Lindsay 1957, p. 420.

- Kubben 2011, p. 148.

- Ward & Leathes 1912, p. 57.

- Elliott 2014, p. 8.

- Colville 1935, p. 149.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 361–362.

- McKay & Scott 1983, pp. 138–140.

- "Golden Age of Piracy – Post Spanish Succession Period". goldenageofpiracy.org. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

Sources

- Anderson, MS (1995). The War of Austrian Succession 1740–1748. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582059504.

- Atkinson, CT (1944). "The Peninsula Second Front in the War of the Spanish Succession". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. JSTOR 44228346.

- Bromley, JS (1970). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 6, The Rise of Great Britain and Russia (1979 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521293969.

- Carlos, Ann; Neal, Larry; Wandschneider, Kirsten (2006). "The Origins of National Debt: The Financing and Re-financing of the War of the Spanish Succession". International Economic History Association.

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688–1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719089964.

- Clodfelter, M. (2008). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (2017 ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Colville, Alfred (1935). Studies in Anglo-French History During the Eighteenth, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1528022392.

- Cowans, Jon (2003). Modern Spain: A Documentary History. U. of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1846-6.

- de Vries, Jan (2009). "The Economic Crisis of the 17th Century". Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 40 (2).

- Dhondt, Frederik (2015). De Ruysscher, D; Capelle, K (eds.). History in Legal Doctrine; Vattel and Réal De Curban on the Spanish Succession; the War of the Spanish Succession in Legal history; moving in new directions. Maklu. ISBN 9789046607589.

- Elliott, John (2014). Dadson, Trevor (ed.). The Road to Utrecht in Britain, Spain and the Treaty of Utrecht 1713–2013. Routledge. ISBN 978-1909662223.

- Falkner, James (2015). The War of the Spanish Succession 1701 – 1714. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1781590317.

- Francis, David (May 1965). "Portugal and the Grand Alliance". Historical Research. 38 (97): 71–93. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1965.tb01638.x.

- Frey, Linda; Frey, Marsha, eds. (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313278846.

- Gregg, Edward (1980). Queen Anne (Revised) (The English Monarchs Series) (2001 ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300090246.

- Hattendorf, John (1979). A Study in the English View and Conduct of Grand Strategy, 1701 - 1713 (PhD). Pembroke College Oxford.

- Hochedlinger, Michael (2003). Austria's Wars of Emergence, 1683–1797. Routledge. ISBN 0582290848.

- Holmes, Richard (2008). Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius. Harper. ISBN 978-0007225729.

- Ingrao, Charles (1979). In Quest & Crisis; Emperor Joseph I and the Habsburg Monarchy (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521785051.

- Ingrao, Charles (2000). The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815 (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521785051.

- Israel, Jonathan (1989). Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585–1740 (1990 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198211396.

- Kamen, Henry (2001). Philip V of Spain: The King Who Reigned Twice. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0253190253.

- Kamen, Henry (1969). The War of Succession in Spain 1700-15. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0300180541.

- Kann, Robert (1974). A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918 (1980 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520042063.

- Kubben, Raymond (2011). Regeneration and Hegemony; Franco-Batavian Relations in the Revolutionary Era 1795–1803. Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-9004185586.

- Lesaffer, Randall (10 November 2014). "The peace of Utrecht and the balance of power". Blog.OUP.com. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Lesaffer, Randall. "Fortress Belgium – The 1715 Barrier Treaty". OUP Law. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Lindsay, JO (1957). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 7, The Old Regime, 1713–1763. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521045452.

- Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714 (Modern Wars in Perspective). Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- McKay, Derek; Scott, HM (1983). The Rise of the Great Powers 1648 – 1815 (The Modern European State System). Routledge. ISBN 978-0582485549.

- Meerts, Paul Willem (2014). Diplomatic negotiation: Essence and Evolution (PhD). Leiden University. hdl:1887/29596.

- Myers (1917). "Violation of Treaties: Bad Faith, Nonexecution and Disregard". The American Journal of International Law. 11 (4): 794–819. doi:10.2307/2188206. JSTOR 2188206.

- Nicholson, Lt.-Col. G. W. L. (1955). Marlborough and the War of the Spanish Succession. Queens Printer.

- Ostwald, Jamel (2014). Murray, Williamson; Sinnreich, Richard (eds.). Creating the British way of war: English strategy in the War of the Spanish Succession in Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107633599.

- Pincus, Steven. "Rethinking Mercantilism: Political Economy, The British Empire and the Atlantic World in the 17th and 18th Centuries". Warwick University.

- Rothbard, Murray (23 April 2010). "Mercantilism as the Economic Side of Absolutism". Mises.org. Good summary of the concept. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Rule, John (2017). The Partition Treaties, 1698–1700 in A European View in Redefining William III: The Impact of the King-Stadholder in International Context. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138257962.

- Schaeper, Thomas (March 1986). "French and English Trade after Utrecht". Journal for Eighteenth Century Studies. 9 (1). doi:10.1111/j.1754-0208.1986.tb00117.x.

- Schmidt Voges, Inken; Solana Crespo, Ana, eds. (2017). Introduction to New Worlds?: Transformations in the Culture of International Relations Around the Peace of Utrecht in Politics and Culture in Europe, 1650–1750). Routledge. ISBN 978-1472463906.

- Shinsuke, Satsuma (2013). Britain and Colonial Maritime War in the Early Eighteenth Century. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843838623.

- Simms, Brendan (2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714–1783. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140289848.

- Somerset, Anne (2012). Queen Anne; the Politics of Passion. Harper. ISBN 978-0007203765.

- Storrs, Christopher (2006). The Resilience of the Spanish Monarchy 1665–1700. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0199246373.

- Sundstrom, Roy A (1992). Sidney Godolphin: Servant of the State. EDS Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0874134384.

- Symcox, Geoffrey (1985). Victor Amadeus; Absolutism in the Savoyard State, 1675–1730. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520049741.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719037740.

- Thompson, Andrew (2014). Dadson, Trevor (ed.). The Utrecht Settlement and its Aftermath in Britain, Spain and the Treaty of Utrecht 1713–2013. Routledge. ISBN 978-1909662223.

- Thompson, RT (1973). Lothar Franz von Schönborn and the Diplomacy of the Electorate of Mainz. Springer. ISBN 978-9024713462.

- Vives, Jaime (1969). An Economic History of Spain. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691051659.

- Ward, William; Leathes, Stanley (1912). The Cambridge Modern History (2010 ed.). Nabu. ISBN 978-1174382055.

- White, Ian (2011). Rural Settlement 1500–1770 in The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. OUP. ISBN 978-0192116963.

- Wolf, John (1968). Louis XIV (1974 ed.). WW Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0393007534.

- Navarro i Soriano, Ferran (2019). Harca, harca, harca! Músiques per a la recreació històrica de la Guerra de Successió (1794-1715). Editorial DENES. ISBN 978-84-16473-45-8

Further reading

- de Bruin, Renger E. et al. Performances of Peace: Utrecht 1713 (Brill, 2011) online

- Gilbert, Arthur N. "Army Impressment During the War of the Spanish Succession." Historian 38$4 1976, pp. 689–708. in Britain

- Thomson, M. A. "Louis XIV and the Origins of the War of the Spanish Succession." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 4, 1954, pp. 111–134. online

External link

Media related to War of the Spanish Succession at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to War of the Spanish Succession at Wikimedia Commons