Petah Tikva

Petah Tikva (Hebrew: פֶּתַח תִּקְוָה, IPA: [ˌpe.taχ ˈtik.va], "Opening of Hope"), also known as Em HaMoshavot ("Mother of the Moshavot"), is a city in the Central District of Israel, 10.6 km (6.6 mi) east of Tel Aviv. It was founded in 1878, mainly by Orthodox Jews of the Old Yishuv, and became a permanent settlement in 1883 with the financial help of Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

Petah Tikva

פֶּתַח תִּקְוָה | |

|---|---|

City (from 1937) | |

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • Also spelled | Petah Tiqwa (official) Petach Tikva, Petach Tikvah (unofficial) |

Petah Tikva High-Tech Park | |

Emblem of Petah Tikva | |

Petah Tikva  Petah Tikva | |

| Coordinates: 32°05′20″N 34°53′11″E | |

| Grid position | 139/166 PAL |

| Country | |

| District | Central |

| Founded | 1878 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rami Greenberg (Likud) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 35,868 dunams (35.868 km2 or 13.849 sq mi) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 247,956 |

| • Density | 6,900/km2 (18,000/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Opening of hope |

| Website | http://www.petah-tikva.muni.il/ |

In 2019 the city had a population of 247,956.[1] Its population density is approximately 6,277 inhabitants per square kilometre (16,260/sq mi). Its jurisdiction covers 35,868 dunams (~35.9 km2 or 15 sq mi). Petah Tikva is part of the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area.

Etymology

Petah Tikva takes its name (meaning "Door of Hope") from the biblical allusion in Hosea 2:15: "... and make the valley of Achor a door of hope."[2] The Achor Valley, near Jericho, was the original proposed location for the town. The city and its inhabitants are sometimes known by the nickname "Mlabes" after the Arab village preceding the town. (See "Ottoman era" under "History" below.)

History

.jpg.webp)

The place where Petah Tikva was founded existed as a village for a long time, immediately previously as a village called Mulabbis.[3]

Crusader and Mamluk era

Khirbat Mulabbis is believed to have been built on the site of the Crusader village of Bulbus, an identification proposed in the nineteenth century by French scholar J. Delaville Le Roulx.(fr) A Crusader source from 1133 CE states that the Count of Jaffa granted the land to the Hospitaller order, including “the mill/mills of the three bridges” (“des moulins des trios ponts”).[4][5][6][7]

In 1478 CE (883 AH), the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt, Qaitbay, endowed a quarter of the revenues of Mulabbis to two newly established institutions: Madrasa Al-Ashrafiyya in Jerusalem, and a mosque in Gaza.[3]

Mulabbis

It has been suggested that Mulabbis was Milus, a village with 42 Muslim households, mentioned in the Ottoman tax records in 1596.[8]

The village appeared under the name of Melebbes on Jacotin's map drawn-up during Napoleon's invasion in 1799,[9] while it was called el Mulebbis on the map of Southern Palestine that Heinrich Kiepert published in 1856.[10] The village was repopulated following Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt's expedition to the Levant (1831-1841) by Egyptian emigrants belonging to the Abu Hamed al-Masri Clan, as part of a wider wave of migration that settled in Palestine's coastal lowlands.[11]

In 1870 Victor Guérin noted that Melebbes was a small village with 140 persons, surrounded by fields of watermelon and tobacco.[12] An Ottoman village list from about the same year showed that Mulebbes had 43 houses and a population of 125, though the population count included men, only. It was also noted that the village was located on a hill, (Auf einer anhöhe"), 2 3/4 hours NE of Jaffa.[13][14]

The Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine visited Mulebbis in 1874 and described it as "a similar mud village [as Al-Mirr], with a well."[15] Following the sale of Mulabbis' lands to Jewish entrepreneurs, its residents dispersed in neighboring villages like Jaljulia and Fajja[11]

Petah Tikva

Petah Tikva was founded in 1878 by religious Jewish pioneers from Europe, among them Yehoshua Stampfer, Moshe Shmuel Raab, Yoel Moshe Salomon, Zerach Barnett,[16] and David Gutmann, as well as Lithuanian Rabbi Aryeh Leib Frumkin who built the first house.[17] It was the first modern Jewish agricultural settlement in Ottoman Southern Syria (hence its nickname as "Mother of the Moshavot").

Originally intending to establish a new settlement in the Achor Valley, near Jericho, the pioneers purchased land in that area. However, Abdülhamid II cancelled the purchase and forbade them from settling there, but they retained the name Petah Tikva as a symbol of their aspirations.

In 1878 the founders of Petah Tikva learned of the availability of land northeast of Jaffa near the village of Mulabes (or Umlabes). The land was owned by two Christian businessmen from Jaffa, Antoine Bishara Tayan and Selim Qassar, and was worked by some thirty tenant farmers. Tayan's property was the larger, some 8,500 dunams, but much of it was in the malarial swamp of the Yarkon Valley. Qassar's property, approximately 3,500 dunams, lay a few kilometers to the south of the Yarkon, away from the swampland. It was Qassar's that was purchased on July 30, 1878. Tayan's holdings were purchased when a second group of settlers, known as the Yarkonim, arrived in Petah Tikva the following year.[18] Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II allowed the purchase because of the poor quality of the land.[19]

A malaria epidemic broke out in 1880, forcing the abandonment of the settlements on both holdings.[20] Those who remained in the area moved south to Yehud. After Petah Tikva was reoccupied by Bilu immigrants in 1883 some of the original families returned. With funding for swamp drainage provided by Baron Edmond de Rothschild, the colony became more stable.[21]

Upon learning that the Austrian post office in Jaffa wanted to open a branch in Petah Tikva, Yitzchak Goldenhirsch, an early resident, offered his assistance on condition that the Austrian consulate issued a Hebrew stamp and a special postmark for Petah Tikva. The stamp was designed by an unknown artist featuring a plow, green fields and a blossoming orange tree. The price was 14 paras (a Turkish coin) and displayed the name 'Petah Tikva' in Hebrew letters.[22]

David Ben Gurion lived in Petah Tikva for a few months on his arrival in Palestine in 1906. It had a population of around 1000, half of them farmers. He found occasional work in the orange groves.[23] But he soon caught malaria and his doctor recommended he return to Europe.[24] The following year, after moving to Jaffa, he set up a Jewish workers organisation in Petah Tikva.[25]

During the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I, Petah Tikva served as a refugee town for residents of Tel Aviv and Jaffa, following their exile by the Ottoman authorities due to their refusal to serve the Ottoman army to fight the invading British forces. The town suffered heavily as it lay between the Ottoman and British fronts during the war.

British Mandate era (1917–1948)

In the early 1920s, industry began to develop in the Petah Tikva region. In 1921, Petah Tikva was granted local council status by the British authorities. Petah Tikva was also the scene of Arab rioting in May 1921, which left four Jews dead.[26]

According to the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Petah Tikva had a total population of 3,032; 3,008 Jews, 22 Muslims and 2 Orthodox Christians.[27][28]

In the 1931 census the population had increased to 6,880 inhabitants, in 1,688 houses.[29] In 1937 it was recognized as a city. Its first mayor, Shlomo Stampfer, was the son of one of its founders, Yehoshua Stampfer.

Petah Tikva, a center of citrus farming, was considered by both the British government and the Jaffa Electric Company as a potentially important consumer of electricity for irrigation. The Auja Concession, which was granted to the Jaffa Electric Company on 1921, specifically referred to the relatively large Jewish settlement of Petah-Tikva. But it was only in late 1929 that the company submitted an irrigation scheme for Petah-Tikva, and it was yet to be approved by the government in 1930.[30]

In 1931 Ben Gurion wrote that Petah Tikva had 5000 inhabitants and employed 3000 Arab labourers.[31]

In the 1930s, the pioneering founders of Kibbutz Yavneh from the Religious Zionist movement immigrated to the British Mandate of Palestine, settling near Petah Tikva on land purchased by a Jewish-owned German company. Refining the agricultural skills they learned in Germany, these pioneers began in 1941 to build their kibbutz in its intended location in the south of Israel, operating from Petah Tikva as a base.[32]

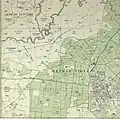

Petah Tiqva 1928 1:20,000

Petah Tiqva 1928 1:20,000 Petah Tiqva 1945 1:250,000

Petah Tiqva 1945 1:250,000

Urban development

After the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, several adjoining villages – Amishav and Ein Ganim to the east (named after the biblical village (Joshua 15:34)), Kiryat Matalon to the west, towards Bnei Brak, Kfar Ganim and Mahaneh Yehuda to the south and Kfar Avraham on the north – were merged into the municipal boundaries of Petah Tikva, giving it a significant population boost to 22,000.

As of 2018, with a population of over 240,000 inhabitants, Petah Tikva is the third most populous city in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area ("Gush Dan").

Petah Tikva is divided into 33 neighborhoods for municipal purposes.[33]

Economy

Petah Tikva is the second-largest industrial sector in Israel after the northern city of Haifa. The industry is divided into three zones—Kiryat Aryeh (named after Aryeh Shenkar, founder and first president of the Manufacturers Association of Israel and a pioneer in the Israeli textile industry), Kiryat Matalon (named after Moshe Yitzhak Matalon), and Segula, and includes textiles, metalwork, carpentry, plastics, processed foods, tires and other rubber products, and soap.[34]

Numerous high-tech companies and start-ups have moved into the industrial zones of Petah Tikva, which now house the Israeli headquarters for the Oracle Corporation, IBM, Intel, Alcatel-Lucent, ECI Telecom, and GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals. The largest data center in Israel, operated by the company TripleC, is also located in Petah Tikva.[35] Furthermore, the Israeli Teva company, the world's largest generic drug manufacturer, is headquartered in Petah Tikva. One of Israel's leading food processing corporations, Osem opened in Petah Tikva in 1976 and has since been joined by the company's administrative offices, distribution center and sauce factory. Strauss is also based in Petach Tikva.[36]

Over time, the extensive citrus groves that once ringed Petah Tikva have disappeared as real-estate developers acquired the land for construction projects. Many new neighborhoods are going up in and around Petah Tikva. A quarry for building stone is located east of Petah Tikva.[37] As well as general hi-tech firms, Petah Tikva has developed a position as a base for many communications firms. As such, the headquarters of the Bezeq International international phone company is located in the Kiryat Matalon industrial zone as are those of the 012 Smile Internet Service Provider. The headquarters of Tadiran Telecom are in the Ramat Siv industrial zone. Arutz Sheva, the right wing Religious Zionist Israeli media network, operates an internet radio studio in Petah Tikva, where Arutz Sheva internet TV is located as well as the printing press for its B'Sheva newspaper.[38]

The Israeli secret service, Shin Bet, has an interrogation facility in Petah Tikva.[39]

Transportation

Petah Tikva is served by a large number of buses. A large number of intercity Egged buses stop there, and the city has a network of local buses operated by the Kavim company. The Dan bus company operates lines to Ramat Gan, Bnei Brak and Tel Aviv.

Petah Tikva's largest bus terminal is the Petah Tikva Central Bus Station (Tahana Merkazit), while other major stations are located near Beilinson Hospital and Beit Rivka. A rapid transit/light rail system is in the works that will connect Petah Tikva to Bnei Brak, Ramat Gan, Tel Aviv and Bat Yam.

Israel Railways maintains two suburban railroad stations in Segula and Kiryat Aryeh, in the northern part of the city. A central train station near the main bus station is envisioned as part of Israel Railways's long-term expansion plan. There are eight taxi fleets based in Petah Tikva, and the city is bordered by three of the major vehicle arteries in Israel: Geha Highway (Highway 4) on the west, the Trans-Samaria Highway (Highway 5) on the north, and the Trans-Israel Highway (Highway 6) on the east.

Santiago Calatrava's bridge, a 164 feet (50 m) long span Y-shaped cable-stayed pedestrian three-way bridge connecting Rabin Hospital to a shopping mall, a residential development and a public park. The structure is supported from a 95-foot (29 m) high inclined steel pylon, which is situated where the three spans intersect. Light in construction, the bridge is built principally of steel with a glass-paved deck.[40]

The Red Line of the Tel Aviv Light Rail system currently under cunstruction will split into 2 branches uppon entrance to Petach Tikva. One branch will travel to an underground terminal at the Kiryat Aryeh railway station, while the other will continue east to the Petach Tikva Central Bus Station. The Light Rail's train depot will also be located at Kiryat Aryeh. It is expected to be completed in 2022[41]

Local government

Petah Tikva's history of government goes back to 1880, when the pioneers elected a council of seven members to run the new colony. From 1880 to 1921, members of the council were David Meir Guttman, Yehoshua Stampfer, Ze'ev Wolf Branda, Abraham Ze'ev Lipkis, Yitzhak Goldenhirsch, Chaim Cohen-Rice, Moshe Gissin, Shlomo Zalman Gissin and Akiva Librecht. This governing body was declared a local council in 1921, and Petah Tikva became a city in 1937. Kadima, the political party founded by former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon, had its headquarters in Petah Tikva.[42]

Council heads and mayors

- Shlomo Zalman Gissin (1921)

- Pinchas Meiri (1922–1928)[43]

- Shlomo Stampfer (1928–1937)

- Shlomo Stampfer (1938–1940)

- Yosef Sapir (1940–1950)

- Mordechai Kraufman (1951)

- Pinchas Rashish (1951–1966)

- Yisrael Feinberg (1966–1978)

- Dov Tavori (1978–1989)

- Giora Lev (1989–1999)

- Yitzhak Ohayon (1999–2013)

- Uri Ohad (2013)

- Itzik Braverman (2013–2018)

- Rami Greenberg (2018–)[44]

Schools and religious institutions

Petah Tikva is home to 300 educational institutions from kindergarten through high school, catering to the secular, religious and Haredi populations. There are over 43,000 students enrolled in these schools, which are staffed by some 2,400 teachers. In 2006, five schools participated in the nationwide Mofet program, which promotes academic excellence. Petah Tikva has seventeen public libraries, the main one located in the city hall building.[45]

Some 70,000 Orthodox Jews live in Petah Tikva. The community of Petah Tikva is served by 300 synagogues,[46] including the 120-year-old Great Synagogue,[47] eight mikvaot (ritual baths)[48] and two major Haredi yeshivot, Lomzhe Yeshiva and Or-Yisrael (founded by the Chazon Ish, Rabbi Avraham Yeshayahu Karelitz). Yeshivat Hesder Petah Tikva, a modern-orthodox Hesder Yeshiva affiliated with the Religious Zionist movement, directed by Rabbi Yuval Cherlow, is also located in Petah Tikva. Additionally, Rav Michael Laitman, PhD in Philosophy and Kabbalah (see Bnei Baruch), daily leads 200-300 students and hundreds of thousands virtually (some estimates of up to 2 million) in the method of Kabbalah learned from his teacher Rav Baruch Ashlag, known as the RABASH.

Petah Tikva has two cemeteries: Segula Cemetery, east of the city, and Yarkon Cemetery, to the northeast.

Health care

Six hospitals are located in the city. The Rabin Medical Center Beilinson complex includes the Beilinson Medical Center, the Davidoff Oncologic Center, the Geha Psychiatric Hospital, the Schneider Pediatric Hospital and Tel Aviv University's Faculty of Medical Research.[49] Other medical facilities in Petah Tikva are HaSharon Hospital, the Beit Rivka Geriatric Center, the Kupat Holim Medical Research Center and a private hospital, Ramat Marpeh, affiliated with Assuta Hospital. The Schneider Pediatric Center is one of the largest and most modern children's hospitals in the Middle East. In addition, there are many family health clinics in Petah Tikva as well as Kupat Holim clinics operated by Israel's health maintenance organizations.

Landmarks and cultural institutions

Petah Tikva's Independence Park includes a zoo at its northeastern edge, the Museum of Man and Nature, a memorial to the victims of the 1921 Arab riots, an archaeological display, Yad Labanim soldiers memorial, a local history museum, a Holocaust museum and the Petah Tikva Museum of Art.[50][51]

Arab–Israeli conflict

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Petah Tikva took over all of the lands of the newly depopulated Palestinian village of Fajja.[52]

During the Second Intifada, Petah Tikva suffered three terrorist attacks: On May 27, 2002, a suicide bomber blew himself up at a small cafe outside a shopping mall, leaving two dead, including a baby;[53] on December 25, 2003, a suicide bomber blew himself up at a bus stop near the Geha bridge, killing 4 civilians,[54][55][56] and on February 5, 2006, a Palestinian got into a shuttle taxi, pulled out a knife, and began stabbing passengers killing two of them, but a worker from a nearby factory hit him with a log, subduing him.[57]

Sports

The main stadium in Petah Tikva is the 11,500-seat HaMoshava Stadium. Petah Tikva has two football teams – Hapoel Petah Tikva and Maccabi Petah Tikva. The local baseball team, the Petach Tikva Pioneers, played in the inaugural 2007 season of the Israel Baseball League. The league folded the following year. In 2014, Hapoel Petah Tikva's women's soccer team recruited five Arab-Israeli women to play on the team. One of them is now a team captain.[58]

Archaeology

In November–December 2006 and May 2007, a salvage excavation was conducted at Khirbat Mulabbis, east of Moshe Sneh Street in Petah Tikva on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Four main strata (I–IV) were identified, dating to the Byzantine period (fourth–seventh centuries CE; Stratum IV), Early Islamic period (eighth–tenth centuries CE; Stratum III), Crusader period (twelfth–thirteenth centuries CE; Stratum II) and Ottoman period (Stratum I).[7]

Notable residents

- Yehuda Amichai (1924–2000), poet

- Zvi Arad (1942-2018), mathematician, acting president of Bar-Ilan University, president of Netanya Academic College

- Hannah Barnett-Trager (1870–1943), wrote about early Petah Tikva[59]

- Hanoch Bartov (1926-2016), author

- Mor Bulis (b. 1996 in Petah Tikva), tennis player

- Tal Burstein (b. 1980 in Petah Tikva), basketball player

- Moran Buzovski (b. 1992), Olympic rhythmic gymnast

- Shmuel Dayan (1891–1968), Zionist activist

- Israel Finkelstein (b. 1949 in Petah Tikva), archaeologist

- Dudu Fisher (b. 1951 in Petah Tikva), cantor and stage performer

- Gal Gadot (b. 1985), actress and model

- Zehava Gal-On (b. 1956), Meretz politician

- A. D. Gordon (1856–1922), Labor Zionist ideologue

- Tamar Gozansky (b. 1940 in Petah Tikva), politician

- Avraham Grant (b. 1955 in Petah Tikva), football coach

- Tzofit Grant (b. 1964 in Petah Tikva), television personality

- Tzachi Halevy (b. 1975 in Petah Tikva), film and television actor, singer

- Simcha Jacobovici (b. 1953 in Petah Tikva), filmmaker

- Doron Jamchi (b. 1961 in Petah Tikva), basketball player

- Yosef Karduner (b. 1969 in Petah Tikva), Hasidic singer-songwriter

- Haim Kaufman (1934–1995), Knesset member

- Yehoshua Kenaz (b. 1937 in Petah Tikva), novelist

- Itzik Kol (1932–2007), television and movie producer

- Alona Koshevatskiy (b. 1997), Olympic rhythmic gymnast

- Amnon Krauz (b. 1952), Olympic swimmer

- Peretz Lavie (b. 1949), expert in the psychophysiology of sleep and sleep disorders, 16th president of the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, Dean of the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine

- Karina Lykhvar (b. 1998), Olympic rhythmic gymnast

- Menachem Magidor (born 1946), mathematician; President of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Samir Naqqash (1938–2004), Iraqi-Jewish author

- Zvi Nishri (Orloff) (1878–1973), physical education pioneer

- Uri Orbach (1960–2015), The Jewish Home politician, journalist and writer

- Elyakum Ostashinski (1909–1983, b. in Petah Tikva), first mayor of Rishon LeZion

- Leah Rabin (1928–2000), wife of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin

- Neta Rivkin (b. 1991), rhythmic gymnast

- Pnina Rosenblum (b. 1954 in Petah Tikva), actress, fashion model, businesswoman and politician

- Nimrod Kamer (b. 1981), poet and class warrior residing in London

- Michal Rozin (b. 1969), Meretz politician

- Rami Saari (b. 1963 in Petah Tikva), poet, translator and linguist

- Dan Shechtman (b. 1941), winner of Nobel Prize for Chemistry[60]

- Sigal Shachmon (b. 1971), model, actress and television presenter

- Giora Spiegel (b. 1947 in Petah Tikva), football player and coach

- Nahum Stelmach (1936–1999), football player

- Pnina Tamano-Shata (b. 1981), politician

In popular culture

Petah Tikva is referenced in the Tony Award-winning musical The Band's Visit, as the main plot derives from a mix-up between the city and the fictional town of "Bet Hatikva" in the Negev Desert of southern Israel.[61]

Twin towns – sister cities

Petah Tikva is twinned with:[62][63][64][65]

Bacău, Romania

Bacău, Romania Cherkasy, Ukraine

Cherkasy, Ukraine Chernihiv, Ukraine

Chernihiv, Ukraine Chicago, United States

Chicago, United States Las Condes, Chile

Las Condes, Chile Gabrovo, Bulgaria

Gabrovo, Bulgaria Gyumri, Armenia

Gyumri, Armenia Kadıköy, Turkey

Kadıköy, Turkey Koblenz, Germany

Koblenz, Germany Międzyrzec Podlaski, Poland

Międzyrzec Podlaski, Poland Șimleu Silvaniei, Romania

Șimleu Silvaniei, Romania Taichung, Taiwan

Taichung, Taiwan Trondheim, Norway

Trondheim, Norway Xinjiang, China

Xinjiang, China

See also

References

- "Population in the Localities 2019" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Petaḥ Tiqwa | Israel". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Marom, Roy (April 3, 2019). "A short history of Mulabbis (Petah Tikva, Israel)". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 151 (2): 134–145. doi:10.1080/00310328.2019.1621734. S2CID 197799335 – via Taylor and Francis+NEJM.

- Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 37, No. 147

- Delaville Le Roulx, 1894, pp. 86−87, No. 97

- Clermont-Ganneau, 1895, pp. 192−196: "Les Trois−Ponts, Jorgilia"

- Haddad, 2013, Petah Tikva, Kh. Mulabbis

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 154. Suggested by David Grossman, 1986, p. 372, cited in Marom, 2019

- Karmon, 1960, p. 170 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Kiepert, 1856, Map of Southern Palestine

- Marom, The village of Mulabbis, Cathedra 176, 2020, pp. 48-64.

- Guérin, 1875, p. 372

- Socin, 1879, p. 158

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 136, also noted 43 houses at Mulebbes

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 252

- זאב וולף ברנדה ז"ל [Ze'ev Wolf Branda memorial] (in Hebrew). Rishonim.org.il. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- "Future Tense – Israel at 60: A Dream Fulfilled". Office of the Chief Rabbi. December 2007. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- Avneri (1984, p. 71); Glass & Kark (1991, pp. 137–138); Ben Ezer (2013) has a more detailed discussion of the Yarkonim, in Hebrew.

- Yaari, Avraham (1958). The Goodly Heritage: Memoirs Describing the Life of the Jewish Community of Eretz Yisrael From the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Centuries. (Translated and abridged by Israel Schen; edited by Isaac Halevy-Levin). Jerusalem: Youth and Hechalutz Dept. of the Zionist Organization. p. 93.

- Yaari (1958, pp. 89–93) suggests that the colonists began to abandon Petah Tikva in late 1880, and had all left in 1881.

- "Petah Tikva". The Jewish Agency for Israel. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- "Lot - An envelope with a Petah Tikva stamp, signed with a special stamp for this stamp". www.auctionzip.com.

- Segev, Tom (2018 - 2019 translation Haim Watzman) A State at Any Cost. The Life of David Ben-Gurion. Apollo. ISBN 9-781789-544633 . p.62

- Segev. p.64

- Segev. p.81

- "Petah Tikvah". Jewish Agency for Israel. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jaffa, p. 20

- Barron, 1923, Table XIV, p. 46

- Mills, 1932, p. 14

- Shamir, Ronen (2013). Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804787062.

- Segev, Tom (2018 - 2019 translation Haim Watzman) A State at Any Cost. The Life of David Ben-Gurion. Apollo. ISBN 9-781789-544633 p.132

- "Kevutsat Rodges (Kevutsat Yavne) est. 1929". Massuah, International Institute for Holocaust Studies.

- "Connect to the Neighborhood". Petah Tikva municipality. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- "DUN'S 100 - 2016". emagazine.globes.co.il.

- Thecom.co.il (in Hebrew) Archived November 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Strauss- Contact Us".

- "Vered Quarry Co Ltd - Company Profile and News". Bloomberg.com.

- "צור קשר".

- "Kept in the Dark". B'Tselem. October 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "Calatrava in Israel: Museum exhibition lands 's Calatrava first project in Israel". World Architecture News. December 15, 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- www.nta.co.il https://www.nta.co.il/en/line/73. Retrieved 2020-12-23. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Hoffman, Gil (September 20, 2007). "Olmert Moves to Keep Kadima United". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- הנהגת הישוב, השלטון המקומי והעומדים בראשם [Community Leadership, local government and their leaders] (in Hebrew). Petah Tikva Summit. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- "Kalisch-Rotem takes Haifa, Huldai keeps Tel Aviv". 2018-10-31.

- "Petah Tikva today". Koblenz–Petah Tikva Friendship Circle. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- "Places to Live – Petah Tikvah". Tehilla – Pilot Trips. Archived from the original on March 23, 2008. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- Stoil, Rebecca Anna (May 4, 2006). "Petah Tikva Synagogue Desecrated". The Jerusalem Post, cited in Pogrom.co.il. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- "List of Mikvaot in the City". Petah Tikva municipality. Archived from the original on January 1, 2009. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- "A hospital's journey from architectural paean to beacon of bad taste".

- Tamar Berger (Summer 2002). "Sleep, Teddy Bear, Sleep: Independence Park, Petach Tikva: An Israeli Realm of Memory". Israel Studies. Indiana University Press. 7 (2): 1–32. doi:10.2979/isr.2002.7.2.1. JSTOR 30245584. S2CID 144392733.

- "Petach Tikva Museum Hosted at Leumi Bet Mani House". Bank Leumi. Archived from the original on 2013-03-27. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 240

- "2000-2006: Major Terror Attacks". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- "Palestinian Bomber Kills 4 Near Tel Aviv - New York Daily News". articles.nydailynews.com. 26 December 2003.

- "Tel Aviv suicide bombing kills four". theage.com.au. Melbourne. 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "USATODAY.com - Israel targets militants after bombing". USA Today. McLean, VA: Gannett. 26 December 2003. ISSN 0734-7456. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Azoulai, Yuval (February 6, 2006). "Israeli Woman Stabbed to Death by Lone Terrorist in Petah Tikva". Haaretz.

- "Israeli Soccer Team Breaks New Ground: Recruits Arab Women". Haaretz. Associated Press. 24 April 2014.

- Pioneers in Palestine: Stories of One of the First Settlers in Petach Tikvah. G. Routledge & sons, Limited. 1923.

- Shtull, Asaf (2011-04-01). "Clear as crystal". Haaretz. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- "The Band's Visit Study Guide" (PDF). The Band's Visit. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "ערים תאומות". petah-tikva.muni.il (in Hebrew). Petah Tikva. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- "Armenian Genocide Memorial to be unveiled in Israel". armenpress.am. Armenpress. 2019-10-10. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- "Kardeş Şehirlerimiz". kadikoy.bel.tr (in Turkish). Kadıköy. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- "Петах Тиква, Израел". gabrovo.bg (in Bulgarian). Gabrovo. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

Bibliography

- Assis, Royee (2012-12-24). "Petah Tiqwa, Mahane Yehuda" (124). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ‘Azab, Anan (2008-10-05). "Petah Tiqwa" (120). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1895). Études d'archéologie orientale (in French). Paris: E. Bouillon.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dagan, Yehuda; Golan, Dor (2009-08-23). "Petah Tiqwa–Rishon Le-Ziyyon, Survey" (121). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dayan, Ayelet (2011-08-03). "Petah Tiqwa, Mahane Yehuda" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Delaville Le Roulx, J. (1894). Cartulaire général de l'Ordre des Hospitaliers (in Latin). 1. Paris.

- Gorzalczany, Amir (2005-11-28). "Petah Tiqwa, Mahane Yehuda" (117). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Haddad, Elie (2013-08-20). "Petah Tiqwa, Kh. Mulabbis" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-22. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Marom, Roy (2019). "A short history of Mulabbis (Petah Tikva, Israel)" (151:2). Palestine Exploration Quarterly: 134–145. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Masarwa, Durar (2012-08-26). "Petah Tiqwa (Mulabbis)" (124). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Masarwa, Durar (2011-12-15). "Petah Tiqwa (Mulabbis)" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (p. 216)

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Toueg, Ron (2013-08-08). "Petah Tiqwa, Mahane Yehuda" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Petah Tikva. |

- Municipality's official website

- Photos of Petah Tikva

- Cadastral map of Petah Tiqva, Ein Ganim, Al Mirr, Mahne Yehuda, 1934 - Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel