Phelps and Gorham Purchase

The Phelps and Gorham Purchase was the purchase in 1788 of 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2) of land in what is now western New York State from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for $1,000,000 (£300,000), to be paid in three annual installments, and the pre-emptive right to the title on the land from the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy for $5000 (£12,500). A syndicate formed by Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham bought preemptive rights to 6,000,000-acre (24,000 km2) in New York, west of Seneca Lake between Lake Ontario and the Pennsylvania border, from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Phelps and Gorham then negotiated with the Seneca nation and other Iroquois tribes to obtain clear title for the entire parcel. They acquired title to only about 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2)[1] east of the Genesee River plus the 12 miles (19 km) by 24 miles (39 km) Mill Yard Tract along the river's northwestern bank. Within a year, monetary values rose and, in combination with poor sales, the syndicate was unable to make the second of three payments for the land west of the Genesee River, forcing them to default on exercising the remainder of the purchase agreement. They were also forced to sell at a discount much of the land they had already bought title to but had not yet re-sold; it was purchased by Robert Morris of Philadelphia, financier, U.S. Founding Father, and Senator. In some sources, the Phelps and Gorham Purchase refers only to the 2,250,000 acres (9,100 km2) on which Phelps and Gorham were able to extinguish the Iroquois' aboriginal title.

Origins and background

Much of the land south of the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario, and west of the Hudson River, had been historically occupied by the Iroquoian-speaking Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy well before any encounter with Europeans. Archaeological evidence suggests that Iroquoian peoples lived in the Finger Lakes region from at least 1000 CE; the nations known to the colonists are believed to have coalesced after that time, and formed their confederacy for internal peace among them.[2] The Mohawk were the easternmost Iroquois tribe, occupying much of the Mohawk Valley west of Albany. The Onondaga and Oneida tribes lived near the eastern edge of this region of land purchases, closer to their namesake lakes, Lake Oneida and Onondaga Lake. (Onondaga territory had extended up to Lake Ontario). The Cayuga and Seneca nations lived to the west in the Finger Lakes region, with the Seneca the westernmost tribe.

Major Iroquois towns in the Finger Lakes region included the Seneca town of Gen-nis-he-yo (present-day Geneseo), Kanadaseaga (Seneca Castle, near present-day Geneva), Goiogouen (Cayuga Castle, east of Cayuga Lake), Chonodote (Cayuga town, present-day Aurora), and Catherine's Town (near present-day Watkins Glen).

The Iroquois nations had earlier formed a decentralized political and diplomatic Iroquois Confederacy. Allied as one of the most powerful Indian confederacies during colonial times, the Iroquois prevented most European colonization west of the middle of the Mohawk Valley and in the Finger Lakes region for nearly two centuries after first contact.

During colonial times, some smaller tribes moved into the Finger Lakes region, seeking the protection of the Iroquois. In about 1720, the Tuscarora tribe arrived, having migrated from the Carolinas after defeat by European colonists and Indian allies. They were also Iroquoian-speaking and were accepted as "cousins", forming the Sixth Nation of the Confederacy.

In 1753 remnants of several Virginia Siouan tribes, collectively called the Tutelo-Saponi, moved to the town of Coreorgonel at the south end of Cayuga Lake (near present-day Ithaca). They lived there until 1779, when their village was destroyed during the Revolutionary War by allied rebel forces.

The French colonized northern areas, moving in along the St. Lawrence River from early trading posts among Algonquian-speaking tribes on the Atlantic Coast; they founded Quebec in 1608. When Samuel de Champlain explored the St. Lawrence River, he claimed the region French Canada as including Western New York. The French sent traders and missionaries there, but ceded any claim in 1759 during the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War, in which they were defeated by Great Britain.[3]

During the American Revolutionary War, four of the six Iroquois nations allied with the British, hoping to push American colonists out of their territory. The Oneida and the Tuscarora became allies of the rebel Americans. Within each tribe, there were often members on either side of the war, as the tribes were highly decentralized. Led by Joseph Brant, a war leader of the Mohawk, numerous Iroquois warriors joined in British attacks against the rebels, particularly in the Mohawk and Schoharie valleys. They attacked and killed settlers, took some women and children as captives, drove off their livestock, and burned their houses and barns.[4] The Iroquois resisted colonists encroaching into their territory, which roughly comprised the Allegheny, Genesee, Upper Susquehanna and Chemung River basins. The Iroquois nations also raided American settlements in Western New York and along the Susquehanna River.[4]

The colonists were angry and hungry for retaliation. In response, on July 31, 1779, Gen. George Washington ordered Gen. James Clinton and Gen. John Sullivan to march from Pennsylvania, near present-day Wilkes-Barre, to the Finger Lakes area of New York. The campaign mobilized 6200 Colonial troops, about 25% of the entire rebel army.[5] Their orders were to

destroy all Indian villages and crops belonging to the six nations, to engage the Indian and Tory marauders under Brandt and Butler whenever possible, and to drive them so far west that future raids would be impossible.[4]

Sullivan led his army on an expedition with the goal of subduing the Iroquois in the region. Although they did not kill many Natives, his forces destroyed much of the Iroquois homelands, including 40 villages such as the major Cayuga villages of Cayuga Castle and Chonodote (Peachtown) and their surrounding fields. In the area from Albany to Niagara, they emptied their winter stores, which included at least 160,000 bushels of stored corn along "with a vast quantity of vegetables of every kind".[5] These actions denied both the Iroquois and the British the food needed to sustain their war effort. The formerly self-sufficient Iroquois fled as refugees, gathering at Fort Niagara to seek food from the British. Weakened by their ordeal and famine, thousands of Iroquois died of starvation and disease. Their warriors no longer were a major factor in the war. The Continental Army took heart from their punishment of the Iroquois on the frontier.[4]

During their advance west, Sullivan's army took a route to New York through northeast Pennsylvania. They had to cut a new road through lightly inhabited areas of the Pocono Mountains (this trail is known today as "Sullivan's Trail"). When the troops returned to Pennsylvania, they told very favorable stories of the region that impressed potential settlers.[4]

Treaty of Hartford

Following the American Revolution, there were a confusing collection of contradictory royal charters from James I, Charles I, and Charles II, mixed with a succession of treaties with the Dutch and with the Indians, which made the legal situation for land sales intractable.[6] Following the war, Great Britain ceded all its claims to the territory, including lands controlled by the Iroquois, who were not consulted.

To stimulate settlement, the federal government planned to release much of these millions of acres of land for sale. Before that could happen, New York and Massachusetts had to settle their competing claims for a region west of New York. (Massachusetts' colonial claim had extended west without end.) The two states signed the Treaty of Hartford in December 1786. With the treaty, Massachusetts ceded its claim to the United States government, and sovereignty and jurisdiction of the region to New York State.

The treaty established Massachusett's pre-emptive rights right to negotiate with the Iroquois nations for their aboriginal title to the land ahead of New York, and also gave the two states the exclusive rights ahead of individuals to buy the land. Anyone else who wanted to purchase title to or ownership of land from the Iroquois was required to first obtain Massachusetts' approval.[6]

After the adoption of the United States Constitution in 1787, the federal government ratified the states' compact.[7] In April 1788, Phelps and Gorham bought the preemptive rights from Massachusetts, but this did not get them the right to develop or re-sell the land. They only obtained exclusive right to negotiate with the Iroquois and obtain clear title to the land. For this preemptive right, they paid Massachusetts $1,000,000 (£300,000) (equivalent to about $15.1 million today) or 16 and 2/3 cents an acre ($41.18/km2). This was to be paid in three annual installments.[8]

By an act of the Massachusetts Legislature approved April 1, 1788,[9] it was provided that "this Commonwealth doth hereby agree, to grant, sell & convey to Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham, for a purchase price of $1,000,000, payable in three equal annual installments all the Right, Title & Demand, which the said Commonwealth has in & to the said 'Western Territory' ceded to it by the Treaty of Hartford."[9] But first Phelps and Gorham had to go up against competing companies and persuade the Iroquois to give up their title to the land.

Council at Buffalo Creek

The New York Genesee Land Company, led by John Livingston, was one of the competitors to acquire title to these lands. He gathered several of the chiefs together at Geneva. To circumvent New York state law that only permitted the state to buy land from the natives, he negotiated a lease for a term of 999 years for all the Iroquois lands of Western New York. This included a down payment of $20,000 and an annual payment of $200 to their heirs. But when New York state learned of his agreement, it advised all parties including the natives that the lease had no standing in either Massachusetts or New York.[10]

Another competitor was the Niagara Genesee Land Company formed by Colonel John Butler, Samuel Street, and other Tory friends of the Iroquois. They tried to persuade the Iroquois to grant them a lease. Some proposed that an independent state be created in western New York.[10][11]

Phelps eliminated many of his competitors by persuading them to join his syndicate. Phelps and Gorham retained 82 shares for themselves, sold 15 shares to the Niagara Genesee Land Company, and divided another 23 shares among 21 persons.[12]

On July 8, 1788, Phelps met with the original Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, including the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations, at Buffalo Creek. His goal was to execute a deed or treaty and obtain title to a portion of their land.[13] The Oneida were split by internal divisions over whether they should give up their title.[14]

Missionary influence

Phelps was aided by Samuel Kirkland, a Presbyterian minister and missionary among the Oneida. Kirkland had been appointed by the state of Massachusetts to oversee the transaction. Kirkland had previously taken part in six prior illegal land treaties made by individual states with the Indians, in violation of federal authority over Indian affairs. Only the US government had the authority to make treaties with the Native American nations.

Kirkland encouraged the Oneida and other Iroquois to sell their land to the whites in part because he was convinced that they "would never become farmers unless forced to by the loss of land for hunting."[14] Kirkland also benefitted from the land sales, receiving 6,000-acre (24 km2) around present day Utica from New York State and from the Oneida people. Kirkland was determined to build the Hamilton-Oneida Academy and needed financial support from the wealthy land speculators.[14] In November 1790, some Iroquois, including Cornplanter, accused Phelps, Kirkland, and the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant of altering deeds in order to favor Phelps.[14]

Land ownership

The Indians believed they were owners of the land, but Phelps persuaded the Chiefs that, since they had been allies to the defeated British during the Revolutionary War, and since the British had given up the lands in the 1783 peace treaty, the tribes could expect to retain only the lands granted by the United States.[10] Phelps and Gorham wanted to buy 2,600,000-acre (11,000 km2), but the Iroquois refused to sell the rights to 185,000 acre (749 km2) west of the Genesee River.

Mill Yard Tract

Phelps suggested that the Iroquois could use a grist mill to grind their maize which would relieve the women of the grinding work. The Indians asked how much land was needed for a grist mill, and Phelps suggested a huge section of land west of the Genesee River, much larger than actually required, extending west from the river 12 miles (19 km), running south from Lake Ontario approximately 24 miles (39 km), and totaling about 288 square miles (750 km2). The section stretches from near the present-day town of Avon north to the community of Charlotte at Lake Ontario and encompasses Rochester. The Iroquois agreed.

Within this area on the west bank, Phelps and Gorham gave 100 acres (0.40 km2; 0.16 sq mi) at the high falls of the Genesee River to Ebenezer "Indian" Allen, on the condition that he build the grist mill and sawmill. The grist mill was distant from potential customers—only about 25 families lived on the west bank at the time—and there were no roads going to it from the few nearby farms on the west bank of the river. It never prospered.[15] Allen's tract became the nucleus of modern Rochester, New York. The section of land on the west bank of the Genesee River became known as the Mill Yard Tract.[16]

Purchase agreement

Phelps and his company paid the Indians $5,000 cash and promised an annual annuity of $500 to their heirs forever.[12] The agreement gave them title to 2,250,000 acres (9,100 km2), included approximately the eastern third of the territory ceded to Massachusetts by the Treaty of Hartford, from the Genesee River in the west to the Preemption Line in the east, which was the boundary that had been set between the lands awarded to Massachusetts and those awarded to New York State by the Treaty of Hartford.

Boundaries established by Phelps' agreement were reaffirmed between the United States and the Six Nations by Article 3 of the Treaty of Canandaigua in 1794.[17] The scrip's low value substantially reduced Massachusetts' proceeds from the sale.[18]

Area boundaries

After the Revolutionary War ended, the Iroquois chiefs had been assured by the US government in the 1784 Fort Stanwix treaty that their lands would remain theirs unless the Indians made new cessions—as a result of regular councils duly convened and conducted according to tribal custom.[10] The eastern boundary was defined by a Preemption Line, which was anchored on the south at the 82nd milestone on the New York-Pennsylvania boundary line and on the north by Lake Ontario. The treaties gave Massachusetts the right to buy from the Native Americans and resell all territory west of the Preemption Line, while New York State retained the right to govern that territory. New York State would add to its territory all land east of the Preemption Line.

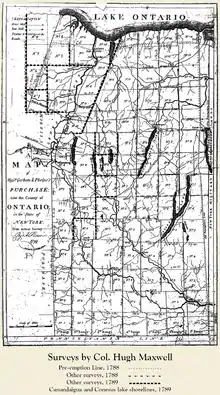

The Fort Stanwix Treaty and earlier treaties established the approximate western boundary, but a survey was required to establish the exact line.[6] Phelps believed that the line ran through Seneca Lake and included the former Cayuga settlement of Kandesaga, present-day Geneva, New York. He planned to make Geneva the headquarters and location of the land sales office. He hired Col. Hugh Maxwell, a man of high reputation, to perform the survey. During his original survey for Phelps and Gorham, Maxwell was assisted by Augustus Porter and other surveyors.[8]

Maxwell and his assistants started a preliminary survey on June 13, 1788 from the 82-mile stone on the Pennsylvania Line. The trial survey reached Seneca Lake. The actual survey was started on July 25, 1788,[19] and when the surveyors reached the area of Kandesaga, the line was fixed west of Seneca Lake and Kandesaga, which survived as a key town in the region. Oliver Phelps was extremely upset when he learned that the survey did not include Seneca Lake or the Indian village. He wrote a letter to Col. William Walker, the local agent responsible for the survey, and requested that they survey be redone in that area. For unknown reasons, it was not completed.[8]

On the west, the survey ran north from the Pennsylvania border to the confluence of Canaseraga Creek and the Genesee River. The survey line followed the river to a point 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Canawagus Village, and then due west 12 miles (19 km) distant from the westernmost bend, and then due north to the shore of Lake Ontario. Maxwell divided the land into ranges 6 miles (9.7 km) wide from north to south.[6] Maxwell's work later became known as "The First Survey."[11]

Settlers arrive

Phelps opened one of the first land sales offices in the U.S. in Suffield, Connecticut[20] and another in Canandaigua. During the next two years, they sold 500,000-acre (2,000 km2) at a higher price to a number of buyers. People arrived from New England, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and from across the Atlantic, from England and Scotland. Settlers also included veterans who had fought under General Sullivan.[11] There was considerable land hunger among people in New England, who had been crowded for some time.

Financial difficulties

Many purchasers were buying land for speculative purposes and quickly resold it. For example, Oliver Phelps sold township 3, range 2, to Prince Bryant of Pennsylvania on September 5, 1789. Prince Bryant sold the land a month later to Elijah Babcock, who in turn sold various parcels to Roger Clark, Samuel Tooker, David Holmes, and William Babcock.[6] The syndicate was able to sell about half of its holdings.

Syndicate defaults

However, within the year, currency values rose in anticipation of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton's plan to nationalize the debts of the states forming the new nation. This raised the value of the consolidated securities Phelps and Gorham had used to buy the land, effectively quadrupling the syndicate's debt[6] and substantially inflating the amount required to purchase title from the Iroquois for the remaining 1,000,000-acre (4,000 km2).[12] The syndicate sold about 50 townships but the purchasers were mainly stockholders who had accepted land in exchange for interest on the loan principal.[8] Fewer emigrants bought land than expected, reducing the income expected by the syndicate. Two of the three bonds financing the purchase were canceled, but even when the debt was reduced to $109,333 (£31,000) (about $1.6 million today), the syndicate was unable to make the next payment. In August 1790, the reverses forced Phelps to sell his Suffield home and his interest in the Hartford National Bank and Trust Co. of Connecticut

In early 1791, the syndicate was unable to make the second payment on the preemptive right to the lands west of the Genesee River, comprising some 3,750,000 acres (15,200 km2), and the land reverted to Massachusetts on March 10, 1791. On March 12, Massachusetts agreed to sell these rights to Robert Morris for $333,333.33 (about $5.02 million today). Morris was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution, and was the major financier of the American Revolution. At the time, he was the richest man in America. Morris paid about 11 or 12 cents an acre for the land, or about $9,878 (£24,695) (about $148,809 today). The land was conveyed to Morris in five deeds on May 11, 1791. On August 10, 1790, the syndicate sold the remaining lands of the Genesee tract directly to Morris, with the exception of about 47,000 acres retained by Phelps and Gorham. The deed was conveyed on November 18, 1790, and specified that the tract should contain 1 million acres, and any amount over that would require further payment.[8]

On September 21, 1791, Geneva was described as "a small, unhealthy village with about 15 houses, all of log construction except three. There are about 20 families."[8]

Survey inaccuracies

When Morris bought the property, issues with the first survey were well known. The purchase deed stated, "A manifest error has been committed in the laying out and dividing the same, so that a new survey must be laid in order to correct the said error."[21] Some accounts from early in the 20th century attribute errors discovered during the second survey to the primitive instruments used by the surveyors, but allegations of fraud were also made. A description of the survey in 1892 cast suspicion on an assistant surveyor named Jenkins, who was supposed to have altered the survey line to favor his employer, Peter Ryckman. He wanted to control the site of present-day Geneva.[8] Ryckman had previously sought to buy the land directly from the Iroquois, but it was illegal under New York state law for him to buy land from the natives, and his contract was voided by the state. When a new survey was commissioned, Maxwell's survey became known as "The First Survey."[22]

Adam Hoops was hired to lead a team of new surveyors, who discovered that Maxwell erred on both the eastern preemption line and the western boundary. Maxwell had located the westernmost boundary of the Millyard Tract in the belief that the Genesee River ran due north. Hoops' team found that Maxwell had made a serious error when he ignored the variance between magnetic north and true north.[6] A survey team that Benjamin Ellicott headed found in November–December 1792 that the preemption line ran through Seneca Lake and north along a line to Lake Ontario near the center of Sodus Bay, about four miles west of the line surveyed by Maxwell.[8] The line now divides the city of Geneva and the Town of Waterloo in Border City. The old preemption line reached Lake Ontario, three miles west of Sodus Bay. The new line terminated near the center of the head of the bay. The new preemption line traveled in a northeasterly direction from the west end of the southern boundary.[19]

In his new survey, Hoops established that the western boundary of the Mill Yard tract included a gore-shaped tract of land about 85,896 acres (347.61 km2; 134.213 sq mi) west of the Genesee River, that should have been retained by the Iroquois. To make it easier, Morris' syndicate returned an equivalent amount of land on the west, a 87,000 acres (350 km2; 136 sq mi) parcel known as the Triangle Tract, to the Iroquois. Morris then purchased the rights to the Triangle Tract from the Iroquois; this land became part of the Morris Reserve.[6] The area of land purchased by Morris was fixed at 1,267,569 acres (5,129.67 km2; 1,980.577 sq mi).[8] Hoop's corrected survey became known as the "Second Survey" and was accepted by Simeon DeWitt, New York's surveyor-general, in a resolution passed by the state on March 24, 1795.[8]

London investors purchase land

After buying the land from the state of Massachusetts in early 1790, Morris almost immediately resold 12,000,000 acres (49,000 km2; 19,000 sq mi) through his London agent William Temple Franklin to the Pulteney Associates, led by Sir William Pulteney. He sold at more than double the price he had paid. Sir William Pulteney bought 9/12ths interest, William Hornby 2/12ths, and Patrick Colquhoun 1/12th interest. At the time non-citizens could not legally hold title to land. The buyers sent Charles Williamson from Scotland, and he was naturalized on January 9, 1792, in order to permit him to hold the land in trust for the owners. He relocated to the United States in February 1792 and settled on the tract.[6] Morris conveyed the deed to Williamson on April 11, 1792 and was paid $333,333 (£75,000). The U.S. Congress had passed The Coinage Act which established the U.S. Mint and the dollar as its official currency only a week before.[8] Morris made a profit of over $160,000 on the transaction.[21]

The Pulteney Purchase, or the Genesee Tract, as it was also known, comprised all of the present counties of Ontario, Steuben and Yates, as well as portions of Allegany, Livingston, Monroe, Schuyler and Wayne counties. After Sir William Pulteney's death in 1805, it was known as the Pulteney Estate.

Holland Land Purchase

Morris sold additional land in December 1792 and in February and July 1793 to the Holland Land Company, an unincorporated syndicate formed by Wilheim Willink and thirteen other Dutch bankers. The bankers hired American trustees in the United States to take title to the land, because U.S. law made it illegal for them to own the property directly. Robert Morris prevailed upon the New York Legislature to repeal that ordinance, which it did shortly thereafter, as it was eager to have the lands developed into settlements.

The investors of the Holland Land Company could in a worst-case scenario resell their property, i.e. the right to purchase aboriginal land. The investors expected a significant profit if they could obtain clear title from the Iroquois and sell unencumbered parcels of land. They organized a council at Big Tree in the summer of 1797. The council was attended by the Iroquois sachems, Robert Morris, James Wadsworth (who represented the Federal Government), and Joseph Ellicott, who represented the Holland Land Company. The Europeans and Americans found Red Jacket, chief of the Seneca nation, very difficult to negotiate with. The Dutch gave presents to the influential women of the tribes, and offered generous payments to several other chiefs to influence their cooperation. They offered the Iroquois about 200,000 acres in return as reservations for the tribes. The result was the Treaty of Big Tree.

In 1802, the Holland Land Company opened its sales office in Batavia, managed by surveyor and agent Joseph Ellicott.[23] The office remained open until 1846 when the company was finally dissolved. The Company granted some plots of land to persons with the condition that they establish improvements, such as inns and taverns, to encourage growth. The building that housed the Holland Land Office still exists; it is operated as a museum dedicated to the Holland Purchase and is designated a National Historic Landmark.

Morris Reserve

Morris kept 500,000 acres (2,000 km2) in a 12-mile-wide (19 km) strip along the east side of the lands acquired from Massachusetts, from the Pennsylvania border to Lake Ontario. This later became known as the Morris Reserve. At the north end of the Morris Reserve, Morris sold a 87,000-acre (350 km2) triangular-shaped tract to Herman Leroy, William Bayard, and John McEvers. This was nicknamed the Triangle Tract. A 100,000-acre (400 km2) tract due west of the Triangle Tract was sold to the State of Connecticut.

In May 1796, John Barker Church accepted a mortgage on another 100,000 acres of the Morris Reserve in present-day Allegany County and Genesee County, against a debt owed to him by Morris.[24] After Morris failed to pay the mortgage, Church foreclosed, and Church's son Philip Schuyler Church acquired the land in May 1800.[24] Philip began the settlement of Allegany and Genesee counties by founding the village of Angelica, New York.[25]

As noted above, in September 1797 under the Treaty of Big Tree, negotiated and signed at Geneseo, New York, Morris gained the remaining title to all the lands west of the Genesee held by the Iroquois. Morris paid $100,000 along with perpetual annuities, among other concessions. He created ten reservations for the Iroquois nations within the purchase; these totalled 200,000 acres (800 km2), in comparison to the millions of acres they had ceded. The remainder of the Morris Reserve was quickly subdivided and settled.

Subdivision into counties of New York

In 1802, the entire Holland Purchase, as well as the 500,000 acre (2,000 km2) Morris Reserve immediately to the east, was split off from Ontario County and organized as Genesee County.

In the ensuing 40 years after Genesee County was formed, it was repeatedly split to form all or parts of the counties of Allegany (1806), Niagara (1808), Cattaraugus (1808), Chautauqua (1808), Erie (1821), Monroe (1821), Livingston (1821), Orleans (1824), and Wyoming (1841).

Legacy

Many of the men who were active in these land sales were honored, either by their business associates or by settlers, in the place names of new villages. Many of the original villages have retained their identity as the central district of a larger town:

- Busti, a town in Chautauqua County, named for agent Paolo Busti

- Cazenovia, a town and its village in Madison County, named for agent Theophilus Cazenove

- Ellicott, a town in Chautauqua County, named for surveyor Joseph Ellicott

- Ellicottville, a town and its village in Cattaraugus County, also named for Joseph Ellicott

- Franklinville, a town and its village in Cattaraugus County, named for agent William Temple Franklin, a grandson of Benjamin Franklin

- Gorham, a town in Ontario County, named for Nathaniel Gorham

- Holland, a town in Erie County, named for the Holland Purchase or the Holland Land Company

- Mount Morris, a town and its village in Livingston County, named for Robert Morris

- Phelps, a town and its village in Ontario County, named for Oliver Phelps

- Williamson, a town in Wayne County, named for Charles Williamson

In contrast, Angelica, a town and its village in Allegany County, were named by landowner Philip Church for his mother, Angelica Schuyler Church.[24][25]

See also

- Fellows v. Blacksmith, 60 U.S. 366 (1857)

- New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble, 62 U.S. 366 (1858)

- Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy, 162 U.S. 283 (1896)

References

- "Rare 18th-century map of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase". Archived from the original on 2017-11-16.

- Jennings, Francis (1988). Empire of Fortune: Crown, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York: Norton. p. 259. ISBN 0-393-30640-2. Archived from the original on 2016-12-31.

- Turner, Orsamus (1852). History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelps & Gorham's Purchase, and Morris' Reserve. Rochester, New York: William Alling. p. 246.

- "Gen. Sullivan's 1779 Campaign Against the Iroqouis". The Daily and Sunday Review. 2001. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- Spiegelman, Bob. "Sullican / Clinton Campaign". Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- Henry, Marian S. (February 25, 2000). "The Phelps-Gorham Purchase". Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- Seneca Nation, 162 U.S. at 285

- Aldrich, Lewis Cass (1893). "VIII. The Phelps and Gorham Purchase". In George S. Conover (ed.). History of Ontario County, New York. Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co. pp. 85–102. At Google Books.

- Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court. Boston: Adams & Nourse. 1893. pp. 900–901. Archived from the original on 2014-07-05.

- McKelvey, Blake (January 1939). "Rochester History" (PDF). Rochester Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Robortella, John M. Steps West: The Field Notes of Col. Hugh Maxwell's Pre-emption Line Survey in the Phelps and Gorham Purchase Archived 2010-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Milliken, Charles F. (1911). A History of Ontario County, New York and Its People Vol. 1. Lewis Historical Publishing Co. pp. 15. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- McKeveley, Blake (January 1939). "Historic Aspects of the Phelps and Gorham Treaty of July 4–8, 1788" (PDF). Rochester History. Rochester Public Library. 1 (1). ISSN 0035-7413. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- Hauptman, Laurence M.; =L. Gordon McLester III, eds. (1999). The Oneida Indian Journey: From New York to Wisconsin, 1784 - 1860. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299161446.

- Merrill, Arch. "Pioneer Profiles". Archived from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Shilling, Donovan A. "Rochester's Romantic Rogue: The Life and Times of Ebenezer Allan". The Crooked Lake Review. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "1794 Canadaigua Treaty Text". Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- Chandler, Alfred N. (2000). Land Title Origins: A Tale of Force and Fraud. Beard Books. p. 568. ISBN 978-1893122895. Archived from the original on 2014-07-05.

- Auten, Betty. "The Gore" (PDF). Seneca County. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- "Oliver Phelps (1749-1809)". Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- Rochester Historical Society (1892). "Publications". Rochester, N.Y. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Robortella, John. "Why Canandaigua Was Chosen". Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- History of Batavia, New York from Our County and Its People: A Descriptive and Biographical Record of Genesee County, New York (1899)

- "Philip Church's Career – One of the Most Prominent of Allegany's Early Settlers". The New York Times. June 23, 1895. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017.

- Minard, John S. (1896). Allegany County and Its People. Alfred, NY: W.A. Ferguson & Co. p. 405.

Further reading

- Hauptman, Laurence M. (2001). Conspiracy of Interests: Iroquois Dispossession and the Rise of New York State. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0712-0.

- McKelvey, Blake (January 1939). "Historical Aspects of the Phelps & Gorham Treaty of July 4–8, 1788" (PDF). Rochester History. 1 (1): 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2005-05-14.

- Robortella, John M., ed. (Spring 2004). "Steps West: The Field Notes of Col. Hugh Maxwell's Pre-emption Line Survey in the Phelps and Gorham Purchase". Crooked Lake Review. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17.

- Turner, Orsamus (1852). History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelps & Gorham's Purchase, and Morris' Reserve. Rochester, N.Y.: William Alling. p. 246. (PDF format)

External links

- Animations of Land Acquisitions (Map Scene 5) – video for Adobe Flash Player