Piano Sonata No. 32 (Beethoven)

The Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111, is the last of Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonatas. The work was written between 1821 and 1822. Like other late period sonatas, it contains fugal elements. It was dedicated to his friend, pupil, and patron, Archduke Rudolf.

| Piano Sonata | |

|---|---|

| No. 32 | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

Title page of the first edition, with dedication | |

| Key | C minor |

| Catalogue | Op. 111 |

| Composed | 1821–22 |

| Dedication | Archduke Rudolf |

| Published | 1822 |

| Movements | 2 |

The sonata consists of only two contrasting movements. The second movement is marked as an arietta with variations. Thomas Mann called it "farewell to the sonata form".[1][2] The work entered the repertoire of leading pianists only in the second half of the 19th century. Rhythmically visionary and technically demanding, it is one of the most discussed of Beethoven's works.

History

Beethoven conceived of the plan for his final three piano sonatas (Op. 109, 110 and 111) during the summer of 1820, while he worked on his Missa solemnis. Although the work was only seriously outlined by 1819, the famous first theme of the allegro ed appassionato was found in a draft book dating from 1801–1802, contemporary to his Second Symphony.[3] Moreover, the study of these draft books implies that Beethoven initially had plans for a sonata in three movements, quite different from that which we know: it is only thereafter that the initial theme of the first movement became that of the String Quartet No. 13, and that what should have been used as the theme with the adagio—a slow melody in A♭—was abandoned. Only the motif planned for the third movement, the famous theme mentioned above, was preserved to become that of the first movement.[4] The Arietta, too, offers a considerable amount of research on its themes; the drafts found for this movement seem to indicate that as the second movement took form, Beethoven gave up the idea of a third movement, the sonata finally appearing to him as ideal.[5]

Along with Beethoven's 33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 (1823) and his two collections of bagatelles—Op. 119 (1822) and Op. 126 (1823)—the sonata was one of Beethoven's last compositions for piano. Nearly ignored by contemporaries, it was not until the second half of the 19th century that it found its way into the repertoire of most leading pianists.[6]

Structure

The work is in two highly contrasting movements:

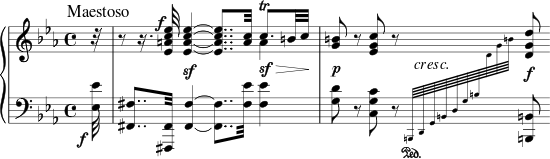

- Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato

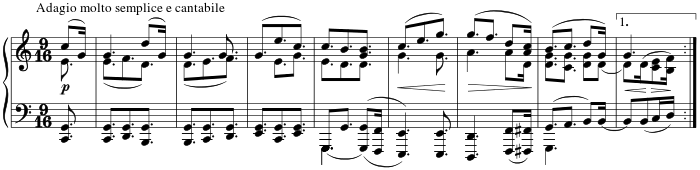

- Arietta: Adagio molto semplice e cantabile

Typical performances take 7–10 minutes for the first movement, and 15–20 minutes for the second, though the range of timings is wide. There are a few recordings that take more than 20 minutes for the second movement, e.g. Barenboim (21 minutes), Afanassiev (22 minutes) and Ugorski (27 minutes).

I. Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato

Duration of roughly 9–11 minutes.

The first movement, like many other works by Beethoven in C minor, is stormy and impassioned—the tempo markings may be translated, respectively, as "majestic" and "brisk, with vigor and passion". It abounds in diminished seventh chords, as in for instance the first full bar of its opening introduction, which may have provided the inspiration for the introduction of Chopin's Second Piano Sonata:[7]

Unlike Beethoven's other C minor sonata-form movements, the exposition of this movement moves to the submediant (A♭ major), not to the mediant, as its second key area. The quiet second theme bears a resemblance to the second theme in the final movement of the fourteenth piano sonata, made even more explicit in the recapitulation where this theme is restated ominously in the bass in minor mode, after initially appearing in C major. Overall, the first movement contains motivic similarities with Mozart's Adagio and Fugue in C minor, which Beethoven arranged for a string quartet (Hess 37).

The A♭ major closing theme of the exposition, based on the first motif of the first theme, initiates a chromatic descent to its dominant with the motif A♭–C–G – and the same motif appears in the theme's restatement in the recapitulation, this time at the culmination of the chromatic descent instead of at the beginning. This moment is also prepared by the inclusion of the minor-mode inflected flattened sixth (F♭) at the corresponding point in the exposition's closing theme.

In a move that mirrors the Piano Sonata, Op. 49 No. 1, and the Cello Sonata, Op. 5 No. 2, Beethoven ends this movement with a Picardy third that directly prepares the major-mode finale.

II. Arietta: Adagio molto semplice e cantabile

Duration of roughly 14–30 minutes

The final movement, in C major, is a set of five variations on a 16-bar theme in 9

16, with a final coda. The last two variations (Var. 4 and 5) are famous for introducing small notes which constantly divide the bar into 27 beats, which is very uncommon. Beethoven eventually introduces a trill which gives the impression of a further acceleration. The tempo marking may be translated "slowly, very simple and songlike."

Beethoven's markings indicate that he wished variations 2–4 to be played to the same basic (ternary) pulse as the theme, first variation and subsequent sections (that is, each of the three intra-bar groupings move at the same speed regardless of time signature; Beethoven uses the direction "L'istesso tempo" at each change of time signature).[8] The simplified time signatures (6

16 for 18

32 and 12

32 for 36

64; both implying unmarked triplets) support this. However, in performance, the theme and first variation sound much slower, with wide spaces between the chords, and the second variation (and much more so, the third variation) faster, because of the shorter note values that create a doubling (and redoubling) of the effective compound time groupings. The third variation has a powerful, stomping, dance-like character with falling swung sixty-fourth notes, and heavy syncopation. Mitsuko Uchida has remarked that this variation, to a modern ear, has a striking resemblance to cheerful boogie-woogie, and the closeness of it to jazz and ragtime, which were still over 70 years into the future at the time, has often been pointed out. Jeremy Denk, for example, describes the second movement using terms like "proto-jazz" and "boogie-woogie".[9] Conversely, András Schiff denounces that hypothesis, maintaining that it has nothing to do with jazz or anything of the sort.[10] From the fourth variation onwards the time signature returns to the original 9

16 but divided into constant triplet thirty-second notes, effectively creating a doubly compound meter (equivalent to 27

32).

The work is one of the most famous compositions of the composer's "late period" and is widely performed and recorded. The pianist Robert Taub has called it "a work of unmatched drama and transcendence ... the triumph of order over chaos, of optimism over anguish."[11] John Lill sees Beethoven's struggle that permeates the first movement as physically challenging pianists performing this work; even in the opening of the sonata, for instance, there is a downward leap of a seventh in the left hand – Beethoven is making his pianists physically struggle to reach the notes.[12] Alfred Brendel commented of the second movement that "what is to be expressed here is distilled experience" and "perhaps nowhere else in piano literature does mystical experience feel so immediately close at hand".[13]

Asked by Anton Schindler why the work has only two movements (this was unusual for a classical sonata but not unique among Beethoven's works for piano), the composer is said to have replied "I didn't have the time to write a third movement." However, according to Robert Greenberg, this may have just as easily been the composer's prickly personality shining through, since the balance between the two movements is such that it obviates the need for a third.[14] Jeremy Denk points out that Beethoven "whittles away everything down to the absolute difference of the two movements", "an Allegro and an Adagio, two opposed poles", and suggests that "as with the greatest Beethoven pieces, the structure itself becomes a message".[9]

Legacy

Chopin greatly admired this sonata. In two of his works, the Second Piano Sonata and the Revolutionary Étude, he alluded to the opening and ending of the sonata's first movement, respectively[15] (compare the opening bars of the two sonatas, and bars 77–81 of Chopin's Étude with bars 150–152 in the first movement of Beethoven's sonata).

Prokofiev based the structure of his Symphony No. 2 on this sonata.

In 2009, the Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero wrote a composition for piano solo entitled Op. 111 – Bagatella su Beethoven, which is a blend of themes from this sonata and Dmitri Shostakovich's musical monogram DSCH.

The work is referenced in chapter 8 of Thomas Mann's novel Doktor Faustus. Wendell Kretschmar, the town organist and music teacher, delivers a lecture on the sonata to a bemused audience, in the fictional town of Kaisersaschern on the Saale, playing the piece on an old piano while declaiming his lecture over the music:

He sat on his revolving stool,... and in a few words brought to an end his lecture on why Beethoven had not written a third movement to op. 111. We had only needed, he said, to hear the piece to answer the question ourselves. A third movement? A new approach? A return after this parting – impossible! It had happened that the sonata had come, in the second, enormous movement, to an end, an end without any return. And when he said 'the sonata', he meant not only this one in C minor, but the sonata in general, as a species, as traditional art-form; it itself was here at an end, brought to its end, it had fulfilled its destiny, resolved itself, it took leave – the gesture of farewell of the D G G motif, consoled by the C sharp, was a leave-taking in this sense too, great as the whole piece itself, the farewell of the sonata form.[1]

In his technical musical excurses, Mann borrowed extensively from Theodor Adorno's Philosophy of Modern Music (and Adorno indeed played this particular opus for Mann), to the extent that some critics consider him as the novel's tacit co-author. The influence is particularly strong in the passages outlining Kretschmar's lectures.[16]

References

- Mann, Thomas (1949). Doctor Faustus. Translated by H. T. Lowe-Porter. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 56.

- Cobley, Evelyn (Spring–Summer 2002). "Avant-Garde Aesthetics and Fascist Politics: Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus and Theodor W. Adorno's Philosophy of Modern Music". New German Critique (p. 63) (86): 43–70. doi:10.2307/3115201. JSTOR 3115201.

- Zwei Skizzenbücher von B. aus den Jahren 1801 bis 1803, Breitkopf, pp. 19 and 14 – cited by R. Rolland, in Beethoven: Les grandes époques créatrices: Le chant de la résurrection – Sablier editions, Paris, 1937, p. 517

- Rolland R., Beethoven: Les grandes époques créatrices: Le chant de la résurrection – Sablier editions, Paris, 1937, pp. 518–520

- Rolland R., Beethoven: Les grandes époques créatrices: Le chant de la résurrection – Sablier editions, Paris, 1937, p. 513

- Jean Witold, Ludwig van Beethoven: The Man and His Work (Paris 1964), p. 140: "The sonata went almost unnoticed by contemporaries and it would be not until later that they came to understand its richness."

- Petty, Wayne C. (Spring 1999). "Chopin and the Ghost of Beethoven". 19th-Century Music. 22 (3): 289.

- Tovey, Donald Francis, Annotations to the Beethoven Piano Sonatas. London: Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, 1932

- Denk, Jeremy (2012). Ligeti / Beethoven (booklet). Nonesuch Records.

- Schiff, András. "Schiff on Beethoven: Part 3. Sonata in C minor, Opus 111, No. 32". The Guardian (podcast).

- Robert Taub. "Robert Taub on The Beethoven Sonatas". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 14 October 2004. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Tania Halban (19 March 2014). "Beethoven Piano Sonata, Op. 111, John Lill". Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Liner notes on a Philips LP with Brendel playing Op. 111 and the Appassionnata, c. 1970.

- Greenberg, Robert, "The Piano Sonatas of Beethoven" Lecture 24. The Teaching Company

- For the allusion in Chopin's second piano sonata, see Petty, Wayne C. (Spring 1999). "Chopin and the Ghost of Beethoven". 19th-Century Music. 22 (3): 281–299. JSTOR 746802.

- Cobley (2002), p. 45

External links

Media related to Piano Sonata No. 32 (Beethoven) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Piano Sonata No. 32 (Beethoven) at Wikimedia Commons- Free recordings at Musopen

- Piano Sonata No. 32: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Recording by Paavali Jumppanen, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum