Polydactyl cat

A polydactyl cat is a cat with a congenital physical anomaly called polydactyly (or polydactylism, also known as hyperdactyly), which causes the cat to be born with more than the usual number of toes on one or more of its paws. Cats with this genetically inherited trait are most commonly found along the East Coast of North America (in the United States and Canada) and in South West England and Wales.

Occurrence

Polydactyly is a congenital abnormality that can be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Some cases of polydactyly are caused by mutations in the ZRS, a genetic enhancer that regulates expression of the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) gene in the limb.[1] The SHH protein is an important signalling molecule involved in patterning of many body elements, including limbs and digits.

Normal cats have a total of 18 toes, with five toes on each fore paw, and four toes on each hind paw; polydactyl cats may have as many as nine digits on their front or hind paws. Both Jake, a Canadian polydactyl cat, and Paws, an American polydactyl cat, were recognised by Guinness World Records as having the highest number of toes on a cat, 28.[2] Various combinations of anywhere from four to seven toes per paw are common.[3] Polydactyly is most commonly found on the front paws only; it is rare for a cat to have polydactyl hind paws only, and polydactyly of all four paws is even less common.[4]

Kitten with 23 toes

Kitten with 23 toes Right front paw of a polydactyl cat. Circles represent digits. The circle with a question mark indicates what might be a separate digit. The rightmost circle is for a small, underdeveloped, clawless digit.

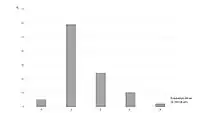

Right front paw of a polydactyl cat. Circles represent digits. The circle with a question mark indicates what might be a separate digit. The rightmost circle is for a small, underdeveloped, clawless digit. Preaxial polydactyly, Hemingway mutant: frequency of polydactylous digits per individual

Preaxial polydactyly, Hemingway mutant: frequency of polydactylous digits per individual Polydactyl Red Maine Coon Kitten

Polydactyl Red Maine Coon Kitten Preaxial polydactyly: ectopic Shh-expression, Hemingway mutant, mouse, right forelimb

Preaxial polydactyly: ectopic Shh-expression, Hemingway mutant, mouse, right forelimb Preaxial polydactyly: Maine Coon cat, Hemingway mutant, right forefoot

Preaxial polydactyly: Maine Coon cat, Hemingway mutant, right forefoot A domestic true polydactyl cat

A domestic true polydactyl cat

History and folklore

The condition seems to be most commonly found in cats along the East Coast of North America (in the United States and Canada)[5] and in South West England, Wales and Kingston-upon-Hull.[4] Polydactyl cats have been extremely popular as ship's cats.[5] Although there is some controversy over whether the most common variant of the trait originated as a mutation in New England or was brought there from Britain, there seems to be agreement that it spread widely as a result of cats carried on ships originating in Boston, Massachusetts, and the prevalence of polydactyly among the cat population of various ports correlates with the dates when they first established trade with Boston.[5] Contributing to the spread of polydactyl cats by this means, sailors were long known to value polydactyl cats especially for their extraordinary climbing and hunting abilities as an aid in controlling shipboard rodents.[5] Some sailors thought they bring good luck at sea.[5] The rarity of polydactyl cats in Europe may be because they were hunted and killed due to superstitions about witchcraft.[5]

Genetic work studying the DNA basis of the condition indicates that many different mutations in the same ZRS area can all lead to polydactyly.[1]

Nobel Prize-winning author Ernest Hemingway was a famous aficionado of polydactyl cats, after being first given, by a ship captain, a six-toed cat he named Snow White.[6][7][8] Upon Hemingway's death in 1961, his former home in Key West, Florida became a museum and a home for his cats, and it currently houses approximately fifty descendants of his cats (about half of which are polydactyl).[8] Because of his love for these animals, polydactyl cats are sometimes referred to as "Hemingway cats".[8][9]

Naming

Nicknames for polydactyl cats include Hemingway cats,[8][9] mitten cats,[8] conch cats, boxing cats, mitten-foot cats, snowshoe cats, thumb cats, six-fingered cats, and Cardi-cats. Two specific breeds recognized by some cat fancier clubs are the American Polydactyl and Maine Coon Polydactyl.

Breeding

American Polydactyl cats are bred as a specific cat breed, with specific physical and behavioral characteristics in addition to extra digits.[10]

The American Polydactyl is not to be confused with the pedigree Maine Coon polydactyl. The polydactyl form of the Maine Coon is being reinstated by some breeders.[11]

Genetics

In the case of preaxial polydactyly of the Maine Coon cat (Hemingway mutant) a mutation of the cis-regulatory element ZRS (ZPA regulator sequence) is associated. ZRS is a noncoding element, 800 kilobasepairs (kb) remote to the target gene SHH. An ectopic expression of SHH is seen on the anterior side of the limb. Normally SHH is expressed in an organiser region, called the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) on the posterior limb side. From there it diffuses anteriorly, laterally to the growth direction of the limb. In the mutant mirroring smaller ectopic expression in a new organiser region is seen on the posterior side of the limb. This ectopic expression causes cell proliferation delivering the raw material for one or more new digits.[12][13] An identical sequence at this position serves the same function in human and mice and cause similar symptoms when mutated. Different mutations have different specific effects: for example, while the Hemingway (Hw) mutant tends to mostly induce extra fingers in the fore limbs, many other mutations affect the posterior limbs too.[1]

Polydactyly is a spontaneous complex phenotypic variation, developed in one generation. In the concrete preaxial form of the Hemingway (Hw) mutant the variation is induced by a single point mutation in a noncoding cis-regulatory element for SHH. In an extensive phenotypic variation like this, one or more complete digits at each single limb are developed including nerves, blood vessels, muscles and ligaments. The physiology of the digits can be perfect. This complex phenotypic result cannot be explained by the mutation alone. The mutation can only induce the variation. In the consequence of the mutation, thousands of events, each different from the wildtype, occur on different organisation layers, such as expression changes of other genes, cell-cell signal exchange, cell differentiation, cell and tissue growth. The summarized small random changes on all layers build the raw material and the process steps for the generation of the plastic variation.[3] The mentioned form of polydactyly of the Hemingway mutant shows a biased variation. In a recent empirical study first the number of extra toes of 375 mutant Maine Coon cats were variable (polyphenism) and second, the number of extra toes followed a discontinuous statistical distribution. They were not equally distributed as one might expect of an identical single point mutation. The example demonstrates that the variation is not explained completely by the mutation alone.[3]

References

- Lettice LA, Hill AE, Devenney PS, Hill RE (2008). "Point mutations in a distant sonic hedgehog cis-regulator generate a variable regulatory output responsible for preaxial polydactyly". Human Molecular Genetics. 17 (7): 978–85. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm370. PMID 18156157.

- "Most toes on a cat". Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- Lange, Axel; Nemeschkal, Hans L.; Müller, Gerd B. (2013). "Biased Polyphenism in Polydactylous Cats Carrying a Single Point Mutation: The Hemingway Model for Digit Novelty". Evolutionary Biology. 41 (2): 262–75. doi:10.1007/s11692-013-9267-y. S2CID 10844604.

- "7 Amazing Facts About Polydactyl Cats". The Spruce Pets. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- JillGat (29 June 1999). Zotti, Ed (ed.). "Is it true many New England cats have extra paws because Boston ships' captains considered them lucky?". The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader. Sun-Times Media Group. ISSN 1096-6919. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

Several sources I checked recounted the story you told, that ships' captains carried them onboard because they were considered lucky (and better mousers, one source said). An article from Cornell University's Cat Watch (1998) looked at studies done on polydactyl cats from the 1940s to the 1970s, and tentatively concluded that the trait probably initially occurred in cats who came over from England to the Boston area with the Puritans in the mid 1600s. There was also speculation in the article that the mutation might have developed in cats already in the Boston area [...] In Europe, polydactyl cats are rare because they were practically wiped out during medieval times due to superstitions about witchcraft (Kelly, Larson, 1993).

- https://www.hemingwayhome.com/cats/

- "11 Writers Who Really Loved Cats". 2013-03-11. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- Syufy, Franny (28 January 2018) [Updated; originally published 20 May 2004]. "The Amazing Hemingway Cats". Cats (Cat FAQs). The Spruce. Dotdash. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- Nichols, Karen (26 September 2008). "The Hemingway Cats Get a Reprieve!". Lifestyle. Catster. Belvoir Media Group. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

In fact, polydactyl cats are often referred to as 'Hemingway Cats.'

- "American Polydactyl". Archived from the original on January 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- Kus, Beth E. "The History of the Polydactyl Maine Coon". Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- Lettice LA, Heaney SJ, Purdie LA, Li L, de Beer P, Oostra BA, Goode D, Elgar G, Hill RE, de Graaff E (2003). "A long-range Shh enhancer regulates expression in the developing limb and fin and is associated with preaxial polydactyly" (PDF). Human Molecular Genetics. 12 (14): 1725–35. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg180. PMID 12837695.

- Lettice LA, Williamson I, Wiltshire JH, Peluso S, Devenney PS, Hill AE, Essafi A, Hagman J, Mort R, Grimes G, DeAngelis CL, Hill RE (2012). "Opposing functions of the ETS factor family define Shh spatial expression in limb buds and underlie polydactyly". Developmental Cell. 22 (2): 459–67. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.010. PMC 3314984. PMID 22340503.

Further reading

- Chapman, V. A.; Zeiner, Fred N. (1961). "The anatomy of polydactylism in cats with observations on genetic control". The Anatomical Record. 141 (3): 205–17. doi:10.1002/ar.1091410305. PMID 13878202. S2CID 44384678.

- Danforth CH (1947). "Heredity of polydactyly in the cat". The Journal of Heredity. 38 (4): 107–12. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a105701. PMID 20242531.

- Danforth, C. H. (1947). "Morphology of the feet in polydactyl cats". American Journal of Anatomy. 80 (2): 143–71. doi:10.1002/aja.1000800202. PMID 20286212.

- Jude, A. C. (1955). Cat genetics. Fond du Lac: All-Pets Books. OCLC 1572542.

- Lockwood, Samuel (1874). "Malformations". The Popular Science Monthly. Vol. IV. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 383.

- Robinson, Roy (1977). Genetics for Cat Breeders (2nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-021209-8.

- Sis RF, Getty R (1968). "Polydactylism in cats". Veterinary Medicine, Small Animal Clinician. 63 (10): 948–51. PMID 5188319.

- Todd NB (1966). "The independent assortment of dominant white and polydactyly in the cat". The Journal of Heredity. 57 (1): 17–8. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107451. PMID 5917255.

- Vella, Carolyn M.; Shelton, Lorraine M.; McGonagle, John J.; Stanglein, Terry W. (1999). Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians (4th ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-4069-5.

- Wenthe, M; Lazarz, B (1995). "Ein Fall von atavistischer Polydaktylie an der Hinterextremität des Hauskatze" [A case of atavistic polydactyly at the hind limb of a cat]. Kleintierpraxis (in German). 40 (8): 617–9.

- Wittmann, F (1992). "Polydactylism in a Cat". Der Praktische Tierarzt. 73 (8): 709.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polydactyl cats. |