Preadolescence

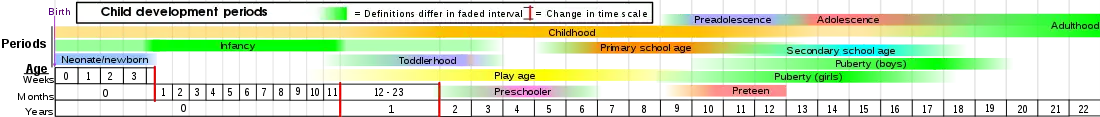

Preadolescence, also known as pre-teen or tween, is a stage of human development following early childhood and preceding adolescence.[1] It commonly ends with the beginning of puberty[2] but may also be defined as ending with the start of the teenage years.[3] For example, the age range is commonly designated as 10–13 years.[4] Preadolescence can bring its own challenges and anxieties.

| Part of a series on |

| Human growth and development |

|---|

|

| Stages |

| Biological milestones |

| Development and psychology |

|

Prepubescence, puberty, and age range

Being prepubescent is not the same thing as being preadolescent. Instead, prepubescent (and sometimes child) is a term for boys and girls who have not developed secondary sex characteristics,[5] while preadolescent is generally defined as those ranging from age 10 to 13 years.[4][6] Preadolescence may also be defined as the period from 9 to 14 years.[7][8]

The point at which a child becomes an adolescent is defined by the onset of puberty or the beginning of the teenage stage.[2][3][5] However, in some individuals (particularly females), puberty begins in the preadolescence years.[9][10] Studies indicate that the onset of puberty has been one year earlier with each generation since the 1950s.[11]

One can also distinguish middle childhood and preadolescence[7] – middle childhood from approximately 5–8 years, as opposed to the time children are generally considered to reach preadolescence.[8] There is no exact agreement as to when preadolescence starts and ends, and research by Gesell et al. suggests that "chronological time...is by no means identical with developmental time" – the duration of the "inner" stages of growth' – or with physiological time.[12]

While known as preadolescent in psychology, the terms preteen, preteenager, or tween are common in everyday use. A preteen or preteenager[1] is a person 12 and under.[13] Generally, the term is restricted to those close to reaching age 12,[1] especially age 11.[14] Tween is an American neologism and marketing term[15] for preteen, which is a blend of between and teen.[13][14] People within this age range are variously described as tweens, preadolescents, tweenies, preteens, pubescents, junior highers,[16] or tweenagers.[17][18]

The term tween was previously used in J. R. R. Tolkien's 1954 novel The Lord of the Rings to refer to hobbits in their twenties: "tweens as hobbits called the irresponsible twenties between childhood and the coming of age at thirty-three."[19] In this context, the word is really either a shortened version of between or a portmanteau of teen and twenty and in either case has no connection to teens, preteens, or the American marketing niche.

Psychological development

Of the 'two major socializing agents in children's lives: the family environment...and formal educational institutions,'[20] it is 'the family in its function a primary socializer of the child'[21] that predominates in the first five years of life: middle childhood by contrast is characterized by 'a child's readiness for school...being self-assured and interested; knowing what kind of behavior is expected...being able to wait, to follow directions, and getting along with other children.'[22]

Preadolescent children in fact have a different view of the world from younger children in many significant ways. Typically, theirs is a more realistic view of life than the intense, fantasy-oriented world of earliest childhood. Preadolescents have more mature, sensible, realistic thoughts and actions: 'the most "sensible" stage of development...the child is a much less emotional being now.'[23] They will often have developed a sense of ' intentionality. The wish and capacity to have an impact, and to act upon that with persistence';[24] and will have a more developed sense of looking into the future and seeing effects of their actions (as opposed to early childhood where children often do not worry about their future). This can include more realistic job expectations ("I want to be an engineer when I grow up", as opposed to "I want to be a wizard"). Middle children generally show more investment 'in control over external reality through the acquisition of knowledge and competence':[25] where they do have worries, these may be more a fear of kidnappings, rapes, and scary media events, as opposed to fantasy things (e.g., witches, monsters, ghosts).

Preadolescents may well view human relationships differently (e.g. they may notice the flawed, human side of authority figures). Alongside that, they may begin to develop a sense of self-identity, and to have increased feelings of independence: 'may feel an individual, no longer "just one of the family."'[26] A different view on morality can emerge; and the middle child will also show more cooperativeness. The ability to balance one's own needs with those of others in group activities'.[27] Many preadolescents will often start to question their home life and surroundings around this time and they may also start to form opinions that may differ from their upbringing in regards to issues such as politics, religion, sexuality, and gender roles.

Greater responsibility within the family can also appear, as middle children become responsible for younger siblings and relatives, as with babysitting; while preadolescents may start caring about what they look like and what they are wearing.

Middle children often begin to experience infatuation, limerence, puppy love, or love itself, though arguably at least with 'girls carrying out all the romantic interest....preadolescent girls' romantic pursuits often seem to be more aggressive than affectionate.'[28]

Preadolescents may still suffer tantrums at the age of 13, sometimes leading to rash decisions regarding risky actions.

Home from home

Where development has been optimal, preadolescents 'come to school for something to be added to their lives; they want to learn lessons...which can lead to their eventually working in a job like their parents.'[29] When earlier developmental stages have gone astray, however, then, on the principle that 'if you miss a stage, you can always go through it later,'[30] some middle children 'come to school for another purpose...[not] to learn but to find a home from home...a stable emotional situation in which they can exercise their own emotional liability, a group of which they can gradually become a part.'[31]

Divorce

Children at the threshold of adolescence in the nine-to-twelve-year-old group[32] would seem to have particular vulnerabilities to parental separation. Among such problems were the very "eagerness of these youngsters to be co-opted into the parental battling; their willingness to take sides...and the intense, compassionate, caretaking relations which led these youngsters to attempt to rescue a distressed parent often to their own detriment".[33]

Media

Preadolescents may well be more exposed to popular culture than younger children and have interests based on internet trends, television shows and movies (no longer just cartoons), fashion, technology, music and social media. Preadolescents generally prefer certain brands, and are a heavily targeted market of many advertisers. Their tendency to buy brand-name items may be due to a desire to fit in, although the desire is not as strong as it is with teenagers.

Some scholars suggest that 'pre-adolescents ... reported frequent encounters with sexual material in the media, valued the information received from it, and used it as a learning resource ... and evaluated such content through what they perceived to be sexual morality.'[34] However, other research has suggested that sexual media influences on preadolescent and adolescent sexual behavior is minimal.[35]

Freud

Freud called this stage the latency period to indicate that sexual feelings and interest went underground ... the feelings that create that first "eternal triangle" with the parents fade, and free energy for other interests and activities.'[36] Erik H. Erikson confirmed that 'violent drives are normally dormant ... a lull before the storm of puberty, when all the earlier drives re-emerge in a new combination, to be brought under the dominance of genitality.'[37]

Latency period children can then direct more of their energy into asexual pursuits such as school, athletics, and same-sex friendships: middle childhood especially is marked by 'the importance of school, teams, classes, friends, gangs and organised activities ... and the adults who run those.'[38] Nevertheless, recent research suggests that "most children do not cease sexual development, interest and behavior" at this time: rather, they "cease to share their interest with adults and are less frequently observed."[39] Because "they've learned the rules ... [they] fit in with the grown-up's belief that they're not interested. But the curiosity about it all continues, and there's quite a lot of experimenting going on between them.'[40] alongside other pursuits

But while the eight-year-old still has "years to wait until puberty, adolescence and finally sexual maturity ... a sort of lull before puberty arrives,'[41] with preadolescence proper (9–12), and the move forward from middle childhood, what have been called 'the introspective and social concerns of the prepubescent'[42] tend to come more to the fore. Clearly "few experiences are more prominent in the lives of preadolescents than the onset of puberty";[43] so that "at eleven or twelve you're just reaching the end of a long period during which change was steady and incremental":[44] Freud's latency years.

See also

References

- New Oxford American Dictionary. 2nd Edition. 2005. Oxford University Press.

- Frank D. Cox, Kevin Demmitt (2013). Human Intimacy: Marriage, the Family, and Its Meaning. Cengage Learning. p. 76. ISBN 978-1285633046. Retrieved February 25, 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Puberty and adolescence". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- Dictionary.com --> Definition of preadolescence (Based on the Random House Dictionary, 2009) Retrieved on July 5, 2009

- Robert C. Manske (2015). Fundamental Orthopedic Management for the Physical Therapist Assistant. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 110. ISBN 978-0323291378. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Nancy T. Hatfield (2007). Broadribb's Introductory Pediatric Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 588. ISBN 978-0781777063. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- William A. Corsaro, The Sociology of Childhood (2005) p. 191 and p. 124

- Donald C. Freeman, Essays in Modern Stylistics (1981) p. 399

- Cecilia Breinbauer (2005). Youth: Choices and Change : Promoting Healthy Behaviors in Adolescents. Pan American Health Organization. p. 303. ISBN 927511594X. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Heather L. Appelbaum (2016). Abnormal Female Puberty: A Clinical Casebook. Springer. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-3319272252. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- G. Ryan et al., Juvenile Sexual Offending (2010) p. 42

- A. Gesell et al., Youth (London 1956) p. 20

- Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Eleventh Edition. 2003. Merriam-Webster.

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Fourth Edition. 2000. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Levasseur, Maïthé (2007-02-09). Familiar with tweens? You should be.... The Tourism Intelligence Network. Retrieved on 2007-12-04.

- Krafft, Bob (1994). Coping With Your Feelings: Five Active Meetings for Your Junior Highers. p. 55.

- Thornburg, Hershel (1974). Preadolescent development. p. 291.

- Hjarvard, Stif Prof (2013). The Mediatization of Culture and Society. p. 107.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. The Lord of the Rings; The Fellowship of the Ring Copyright 1965 by J.R.R Tolkien; Ballantine Books, A Division of Random House Inc. SBN 345-24032-4-150. US$1.50. ISBN 0-345-24032-4.

- Dafna Lemish, Children and Television (Oxford 2007) p. 181

- David Cooper, The Death of the Family (Penguin 1974) p. 26

- Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (London 1996) p. 193

- Mavis Klein, Okay Parenting (1991) p. 13 and p. 78

- daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (London 1996) p. 194

- Mavis Klein, Okay Parenting (1991) p. 13

- E. Fenwick/T. Smith, Adolescence (London 1993) p. 29

- Goleman, p. 194

- Giselle Liza Anatol, Reading Harry Potter: Critical Essays (2003) p. 20

- D. W. Winnicott, The Child, the Family, and the Outside World (Penguin 1973) p. 207

- Skynner/Cleese, p. 24

- Winnicott, p. 208

- Ann Charlton, Caught in the Middle (London 2003) p. 90

- Charlton, p. 90

- Dafna Lemish, Children and Television (Oxford 2007) p. 116

- Steinberg, L., & Monahan, K. 2010. Developmental Psychology.

- Robin Skynner/John Cleese, Families and how to survive them (London 1994) p. 271 and p. 242

- Erik H Erikson, Childhood and Society (Penguin 1973) p. 252

- Lisa Miller, Understanding Your 8 year old (London 1993) p. 26

- Ryan, Juvenile p. 41-42

- Skynner/Cleese, Families p. 271

- Miller, p. 23 and p. 75

- Michell Landsberg, The World of Children's Books (London 1988) p. 270

- Anatol, Potter p. 21

- Francis Spufford, The Child that Books Built (London 2002) p. 163

Further reading

The dictionary definition of Wikisaurus:preteen at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Wikisaurus:preteen at Wiktionary- Myers, James. "Tweens and cool", Admap, March 2004.

- G. Berry Brazelton, Heart Start: The Emotional Foundations of School Readiness 9Arlington 1992)

| Preceded by Childhood |

Stages of human development Preadolescence |

Succeeded by Adolescence |