Prehistoric Korea

Prehistoric Korea is the era of human existence in the Korean Peninsula for which written records do not exist. It nonetheless constitutes the greatest segment of the Korean past and is the major object of study in the disciplines of archaeology, geology, and palaeontology.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Korea | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Prehistoric period | ||||||||

| Ancient period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Proto–Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Northern and Southern States period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Later Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Dynastic period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Colonial period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Modern period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||

Geological prehistory

Geological prehistory is the most ancient part of Korea's past. The oldest rocks in Korea date to the Precambrian. The Yeoncheon System corresponds to the Precambrian and is distributed around Seoul extending out to Yeoncheon-gun in a northeasterly direction. It is divided into upper and lower parts and is composed of biotite-quartz-feldspar schist, marble, lime-silicate, quartzite, graphite schist, mica-quartz-feldspar schist, mica schist, quartzite, augen gneiss, and garnet-bearing granitic gneiss. The Korean Peninsula had an active geological prehistory through the Mesozoic, when many mountain ranges were formed, and slowly became more stable in the Cenozoic. Major Mesozoic formations include the Gyeongsang Supergroup, a series of geological episodes in which biotite granites, shales, sandstones, conglomerates andesite, basalt, rhyolite, and tuff that were laid down over most of present-day Gyeongsang-do Province.

The remainder of this article describes the human prehistory of the Korean Peninsula.

Periodization

Historians in Korea use the three-age system to classify Korean prehistory. The three-age system was applied during the post-Imperial Japanese colonization period as a way to refute the claims of Imperial Japanese colonial archaeologists who insisted that, unlike Japan, Korea had "no Bronze Age".[1]

- Bissalmuneui or Jeulmun pottery period ("Neolithic") 8000–1500 BCE

- Incipient 8000-6000 BCE

- Early 6000–3500 BCE

- Middle 3500–2000 BCE

- Late 2000–1500/1000 BCE

- Mumun pottery period ("Bronze Age") 1500/1000–300 BCE

- Samhan / Proto–Three Kingdoms Period ("Iron Age") 100 BCE to 300 CE

There are some problems with the three-age system applied to the situation in Korea. This terminology was created to describe prehistoric Europe, where sedentism, pottery and agriculture go together to characterize the Neolithic stage. The periodization scheme used by Korean archaeologists proposes that the Neolithic began in 8000 BCE and lasted until 1500 BCE. This is despite the fact that palaeoethnobotanical studies indicate that the first bona fide cultivation did not begin until circa 3500 BCE. The period of 8000 to 3500 BCE corresponds to the Mesolithic cultural stage, dominated by hunting and gathering of both terrestrial and marine resources.[2]

Korean archaeologists traditionally (until the 1990s) used a date of 1500 or 1000 BCE as the beginning of the Bronze Age. This is in spite of bronze technology not being adopted in the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula until circa 700 BCE, and the archaeological record indicates that bronze objects were not used in relatively large numbers until after 400 BCE. This does leave Korea with a proper Bronze Age, albeit a relatively short one, as bronze metallurgy began to be replaced by ferrous metallurgy soon after it had become widespread.[3]

Paleolithic

The origins of this period are an open question but the antiquity of hominid occupation in Korea may date to as early as 500,000 BCE. Yi and Clark are somewhat skeptical of dating the earliest occupation to the Lower Palaeolithic.[4]

At Seokjang-ri, an archaeological site near Gongju, Chungcheongnam-do Province, artifacts that appear to have an affinity with Lower Paleolithic stone tools were unearthed in the lower levels of the site. Bifacial chopper or chopping-tools were also excavated. Hand axes and cleavers produced by men in later eras were also uncovered.

From Jeommal Cave a tool, possibly for hunting, made from the radius of a hominid was unearthed, along with hunting and food preparation tools of animal bones. The shells of nuts collected for nourishment were also uncovered.

In Seokjang-ri and in other riverine sites, stone tools were found with definite traces of Palaeolithic tradition, made of fine-grain rocks such as quartzite, porphyry, obsidian, chert, and felsite manifest Acheulian, Mousteroid, and Levalloisian characteristics. Those of the chopper tradition are of simpler in shape and chipped from quartz and pegmatite. Seokjang-ri's middle layers showed that humans hunted with these bola or missile stones.

During the Middle Paleolithic Period, humans dwelt in caves at the Jeommal Site near Jecheon and at the Durubong Site near Cheongju. From these two cave sites, fossil remains of rhinoceros, cave bear, brown bear, hyena and numerous deer (Pseudaxi gray var.), all extinct species, were excavated.

The earliest radiocarbon dates for the Paleolithic indicate the antiquity of occupation on the Korean peninsula is between 40,000 and 30,000 BCE.[5] From an interesting habitation site at Locality 1 at Seokjang-ri, excavators claim that they excavated some human hairs of Mongoloid origin along with limonitic and manganese pigments near and around a hearth, as well as animal figurines such as a dog, tortoise and bear made of rock. Reports claim that these were carbon dated to some 20,000 years ago.

The Palaeolithic ends when pottery production begins c 8000 BCE.

Jeulmun pottery period

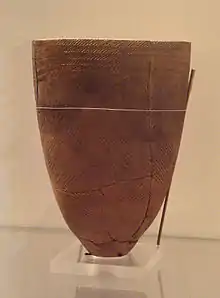

The earliest known Korean pottery dates back to c 8000 BCE or before. This pottery is known as Yunggimun pottery (ko:융기문토기) is found in much of the peninsula. Some examples of Yunggimun-era sites are Gosan-ri in Jeju-do and Ubong-ri in Greater Ulsan. Jeulmun or Comb-pattern pottery (즐문토기) is found after 7000 BC, and pottery with comb-patterns over the whole vessel is found concentrated at sites in west–central Korea between 3500–2000 BC, a time when a number of settlements such as Amsa-dong and Chitam-ni existed. Jeulmun pottery bears basic design and form similarities to that of the Russian Maritime Province, Mongolia, the Amur and Sungari River basins of Manchuria, the Baiyue of southeastern China and the Jōmon culture in Japan.[6]

The people of the Jeulmun practiced a broad spectrum economy of hunting, gathering, foraging, and small-scale cultivation of wild plants. It was during the Jeulmun that the cultivation of millet and rice was introduced to the Korean peninsula from the Asian continent.

Mumun Pottery Period

Agricultural societies and the earliest forms of social-political complexity emerged in the Mumun pottery period (c 1500–300 BCE). People in southern Korea adopted intensive dry-field and paddy-field agriculture with a multitude of crops in the Early Mumun Period (1500–850 BCE). The first societies led by chiefs emerged in the Middle Mumun (850–550 BCE), and the first ostentatious elite burials can be traced to the Late Mumun (c 550–300 BCE). Bronze production began in the Middle Mumun and became increasingly important in Mumun ceremonial and political society after 700 BCE. The Mumun is the first time that villages rose, became large, and then fell: some important examples include Songgung-ni, Daepyeong, and Igeum-dong. The increasing presence of long-distance exchange, an increase in local conflicts, and the introduction of bronze and iron metallurgy are trends denoting the end of the Mumun around 300 BCE.

The Bronze Age reaches Korea beginning about 800 BCE, via Chinese transmission.[7] Bronze metallurgy does not become widespread until the 4th century BCE and soon gives way to the transition to ferrous metallurgy, complete by about the 1st century BCE.

Iron Age

The transition from the Late Bronze to Early Iron Age in Korea begins in the 4th century BCE. This corresponds to the later stage of Gojoseon, the Jin state period in the south, and the Proto–Three Kingdoms period of the 1st to 4th century CE.[8]

The period that begins after 300 BCE can be described as 'protohistoric', a time when some documentary sources seem to describe societies in the Korean peninsula. The historical polities described in ancient texts such as the Samguk Sagi are an example.

The historical period in Korea begins in the late 4th to mid 5th centuries, when as a result of the transmission of Buddhism, the Korean Three Kingdoms modified Chinese writing to produce the earliest records in Old Korean.

Mythological prehistory

Ancient texts such as the Samguk Sagi, Samgungnyusa, Book of the Later Han, and others have sometimes been used to interpret segments of Korean prehistory. The most well-known version of the founding legend that relates the origins of the Korean ethnicity explains that a mythical "first emperor", Dangun, was born from the child of the creator deity's son and his union with a female bear in human form. Dangun built the first city.[9] A significant amount of historical inquiry in the twentieth century was devoted to the interpretation of the accounts of Gojoseon (2333–108 BCE), Gija Joseon (1122–194 BCE), Wiman Joseon (194–108 BCE), and others mentioned in historical texts.

References

- Kim, Seung Og. 1996. "Political Competition and Social Transformation: The Development of Residence, Residential Ward, and Community in Prehistoric Taegongni of Southwestern Korea". PhD dissertation, University of Michigan.

- Choe, C P and Martin T Bale (2002) Current Perspectives on Settlement, Subsistence, and Cultivation in Prehistoric Korea. Arctic Anthropology 39(1–2): 95–121. ISSN 0066-6939

- Kim 1996 Lee, June-Jeong. 2001 From Shellfish Gathering to Agriculture in Prehistoric Korea: The Chulmun to Mumun Transition. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madision. Proquest, Ann Arbor.

- Yi Seon-bok and G A Clark. 1983 Observations on the Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Northeast Asia. Current Anthropology 24(2): 181–202.

- Bae, Kidong. 2002 Radiocarbon Dates from Palaeolithic Sites in Korea. Radiocarbon 44(2): 473–476.

- Stark, Miriam T (2005). Archaeology Of Asia. Blackwell Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 1-4051-0212-8.

- Mary E. Connor, "The Korea, A global studies handbook", 2002, pp. 9

- Barnes (1993): Early Bronze c. 5th to 4th c. BCE, Early Iron (Late Bronze) c. 3rd to 1st c. BCE. Choe & Bale (2002): Mumun (Bronze): mid 2nd millennium BCE to 4th c. BCE, Early Iron: 3rd c. BCE to 1st c. BCE.

- Connor, Mary E. (2002). The Koreas: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-277-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Ahn, Jae-ho. (2000) Hanguk Nonggyeongsahoe-ui Seongnip [The Formation of Agricultural Society in Korea]. Hanguk Kogo-Hakbo [Journal of the Korean Archaeological Society] 43: 41–66. ISSN 1015-373X

- Bae, Kidong 2002. "Radiocarbon Dates from Palaeolithic Sites in Korea", Radiocarbon 44(2):473-476.

- Bale, Martin T. (2001) Archaeology of Early Agriculture in Korea: An Update on Recent Developments. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 21(5): 77–84. ISSN 0156-1316

- Bale, Martin T and Min-jung Ko (2006) Craft Production and Social Change in Mumun Period Korea. Asian Perspectives 45(2): 159–187.

- Barnes, Gina L 1993. China, Korea, and Japan: The Rise of Civilization in East Asia. Thames and Hudson, London.

- Choe, C P and Martin T Bale (2002) Current Perspectives on Settlement, Subsistence, and Cultivation in Prehistoric Korea. Arctic Anthropology 39(1–2): 95–121. ISSN 0066-6939

- Crawford, Gary W and Gyoung–Ah Lee (2003) Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity 77(295): 87–95.

- Im, Hyo-jae (2000) Hanguk Sinseokgi Munhwa [Neolithic Culture in Korea]. Jibmundang, Seoul. ISBN 89-303-0257-2

- Kim, Jangsuk (2003) Land-use Conflict and the Rate of Transition to Agricultural Economy: A Comparative Study of Southern Scandinavia and Central-western Korea. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 10(3): 277–321.

- Kuzmin, Yaroslav V (2006) Chronology of the Earliest Pottery in East Asia: Progress and Pitfalls. Antiquity 80: 362–371.

- Lee, Sung-joo 1998. Silla-Gaya Sahoe-eui Giwon-gwa Seongjang (The Rise and Growth of Society in Silla and Gaya). Hakyeon Munhwasa, Seoul.

- Nelson, Sarah M (1993) The Archaeology of Korea. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-40783-4

- Nelson, Sarah M (1999) Megalithic Monuments and the Introduction of Rice into Korea. In The Prehistory of Food: Appetites for Change, edited by C. Gosden and J. Hather, pp. 147–165. Routledge, London.

- Rhee, S N and M L Choi (1992) Emergence of Complex Society in Prehistoric Korea. Journal of World Prehistory 6: 51–95.