Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi

The Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (in Māori: ngā mātāpono o te tiriti), in New Zealand law and politics, are a set of principles derived from, and interpreting, the Treaty of Waitangi. They are partly an attempt to reconcile the different te reo Māori and English language versions of the Treaty, and allow the application of the Treaty to a contemporary context.[1]

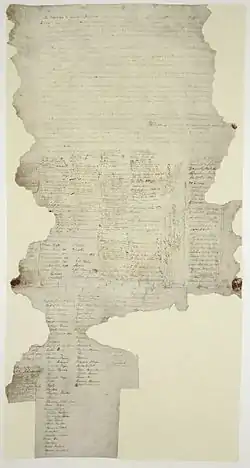

.jpg.webp)

The principles of the Treaty are often mentioned in contemporary New Zealand politics.[2]

Need for Treaty principles

The Treaty is not regarded as law because "the English and Māori versions are not exactly the same", and "it focuses on the issues relevant at the time it was signed."[3] As well as this, New Zealand law affirms the common law doctrine that "any rights purporting to be conferred by a treaty of cession cannot be enforced in the courts, except in so far as they have been incorporated in the municipal law".[4] However, the Treaty of Waitangi is still a pivotal document, and should be used in legislation and health approaches to achieve a more equitable nation, and reverse the effects of colonisation upon the arrival of the European settlers in 1840.

Origins of the principles

The principles originate from the famous case brought in the High Court by the New Zealand Māori Council (New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General[5]) in 1987. There was great concern at that time about the ongoing restructuring of the New Zealand economy by the then Fourth Labour Government, specifically the transfer of assets from former Government departments to State-owned enterprises. Because the state-owned enterprises were essentially private firms owned by the government, there was an argument that they would prevent assets which had been given by Māori for use by the state from being returned to Māori by the Waitangi Tribunal and through Treaty settlements. The Māori Council sought enforcement of section 9 of the State Owned Enterprises Act 1986 which reads: "Nothing in this Act shall permit the Crown to act in a manner that is inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi".[6]

The Court of Appeal, in a judgement of its then President Sir Robin Cooke, decided upon the following Treaty principles:

- The acquisition of sovereignty in exchange for the protection of rangatiratanga.

- The Treaty established a partnership, and imposes on the partners the duty to act reasonably and in good faith.

- The freedom of the Crown to govern.

- The Crown's duty of active protection.

- The duty of the Crown to remedy past breaches.

- Māori to retain rangatiratanga over their resources and taonga and to have all the privileges of citizenship.

- Duty to consult.

Fourth Labour Government's principles

In 1989, the Fourth Labour Government adopted the "Principles for Crown Action on the Treaty of Waitangi". Therese Crocker has argued that Labour's publication of the principles "comprised one of a number of Crown responses to what is generally known as the 'Maori Renaissance'."[7] Prime Minister David Lange, in an introduction to the document said of the principles that:

They [the principles] are not an attempt to rewrite the Treaty of Waitangi. These Crown principles are to help the Government make decisions about matters related to the Treaty. For instance, when the Government is considering recommendations from the Waitangi Tribunal.

I have said that the Treaty of Waitangi has the potential to be our nation's most powerful unifying symbol. I trust that these principles demonstrate that there is a place for all New Zealanders within the Treaty of Waitangi.[8]

The principles in the 1989 publication are as follow:

This principle describes the balance between articles 1 and 2: the exchange of sovereignty by the Māori people for the protection of the Crown. It was emphasised in the context of this principle that "the Government has the right to govern and make laws".[10]

The Government also recognised the Court of Appeal's description of active protection, but identified the key concept of this principle as a right for iwi to organise as iwi and, under the law, to control the resources they own.

The third Article of the Treaty constitutes a guarantee of legal equality between Maori and other citizens of New Zealand. This means that all New Zealand citizens are equal before the law. Furthermore, the common law system is selected by the Treaty as the basis for that equality although human rights accepted under international law are incorporated also.

Reasonable cooperation can only take place if there is consultation on major issues of common concern and if good faith, balance, and common sense are shown on all sides. The outcome of reasonable cooperation will be partnership.[13]

The Principles in legislation

The Treaty of Waitangi principles have impacted and enacted various legislation in particular issues in regards to property or land and many other social, legal and political aspects that affected one or more of the principles. The principles therefore have strong influence on not only the decision making of governments but also on laws.[15]

The following legislation were established due to a significant amount of influence by the Treaty of Waitangi principles and are only a few of many applications of principles within laws:

Fisheries Act 1983

Environment Act 1986

State Owned Enterprises Act 1986

Conservation Act 1987

Resource Management Act 1991

Crown Minerals Act 1991

Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011

Opposition to the principles

Principles Deletion Bill, 2005

The "Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Deletion Bill" was introduced to the New Zealand Parliament in 2005 as a private member's bill by New Zealand First MP Doug Woolerton. "This bill eliminates all references to the expressions "the principles of the Treaty", "the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi" and the "Treaty of Waitangi and its principles" from all New Zealand Statutes including all preambles, interpretations, schedules, regulations and other provisos included in or arising from each and every such Statute".[16]

At the first reading of the Bill, New Zealand First leader Winston Peters said:

this is not an attack on the treaty itself, but on the insertion of the term "the principles of the Treaty" into legislation.

...

This bill seeks to do three fundamental things. First, as the bill's title implies, it seeks to remove all references to the undefined and divisive term "the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi" from legislation. Second, it seeks to reverse the insidious culture of division that has grown up around the existence of these principles. It has seen Māori pitted against Māori and non-Māori, seen family members pitted against each other, and gone right to the heart of our social fabric. Finally, the bill aims to put an end to the expensive and never-ending litigious programme that has sprung up around these principles. This programme has diverted hundreds of millions of dollars into dead-end paths and away from the enlightened programmes that are the true pathway to success.[17]

The bill failed to pass its second reading in November 2007.[18]

In a legal analysis of the bill for Chapman Tripp, David Cochrane argued that without the principles it would probably be an "impossible task" for the Waitangi Tribunal to carry out its role.[1]

Notes

- Cochrane, David (5 May 2005). "What are the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi? What should the law do about them?". Chapman Tripp. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- He Tirohanga ō Kawa ki te Tiriti o Waitangi: a guide to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi as expressed by the Courts and the Waitangi Tribunal (PDF). Te Puni Kokiri. 2001. ISBN 0-478-09193-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Hayward, Janine (October 2014). "Story: Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi – ngā mātāpono o te tiriti". Te Ara. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Te Heuheu Tukino v Aotea District Maori Land Board (PC) [1941] NZLR 590". www.nzlii.org. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- New Zealand Māori Council v. Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641.

- "State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Crocker, Therese, "Introduction" in Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 5

- Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 1

- Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 9

- Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 7

- Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 10

- Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 12

- Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 14

- Principles of the Treaty for Crown Action, p 15

- Mark Hickford, 'Law of the foreshore and seabed', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/law-of-the-foreshore-and-seabed (accessed 28 May 2018)

- "Doug Woolerton's Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Deletion Bill". New Zealand First. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- "Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Deletion Bill – First Reading". New Zealand Parliament. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "New Zealand Parliament – Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Deletion Bill". Parliament.nz. 7 November 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

References

- Principles for Crown Action on the Treaty of Waitangi, 1989. Wellington: Treaty of Waitangi Research Unit, Victoria University of Wellington. 2011.