Raymond Elder

Raymond Elder (c.1962 – 31 July 1994) was a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary and a prominent figure within the Ulster Defence Association's South Belfast Brigade. Suspected by security forces of playing a role in numerous killings, including the Sean Graham shooting, he was shot dead by the Irish Republican Army on the Ormeau Road in 1994.

Early life

A native of Belfast, Elder grew up in the Annadale Flats, an Ulster loyalist area in South Belfast close to the Ormeau Road.[1] Although some individual districts in the Ormeau Road were divided along sectarian lines there were no peace lines, several mixed streets and the main road was frequented by both Protestants and Catholics. As such, Elder knew many Catholics and in his youth was involved in sectarian bullying and street fights before he graduated to UDA membership.[2] He was nicknamed "Snowy" on account of his blond hair.[3]

Ulster Defence Association

Elder was the right-hand man of Joe Bratty, the officer in command of the UDA's south Belfast Brigade during the early 1990s, a period of intense UDA activity. He was charged in relation to the Sean Graham shooting on the lower Ormeau Road in 1992. He had been identified as one of the gunmen by numerous witnesses.[4] Elder was charged for his involvement in the attack although all charges were dropped due to a lack of evidence.[5]

Elder was close personally to sometime UDA West Belfast Brigade leader Johnny Adair and sometimes partied with Adair's group of C Company associates at shebeens on the Shankill Road.[6] Soon after the charges relating to the Sean Graham attack (which Adair had helped to plan) were dropped, Elder accompanied Adair to a UDA ceremony in Scotland where the West Belfast leader presented Elder with a gold ring inscribed with the letters "UFF" as a memento of the attack.[5]

Elder's unit, commanded by Joe Bratty, killed numerous Catholics in this period, including Michael Gilbride[7] and Teresa Clinton, the wife of a local Sinn Féin councillor in the lower Ormeau district.[8]

Death

On 31 July 1994, Elder was shot dead along with Joe Bratty by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). Two men armed with AK-47 assault rifles leapt from a van that was parked in front of their car and fired at Elder and Bratty. The getaway car was pursued by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in an unmarked patrol car, who also fired shots, and brought to a halt at the bottom of Hatfield Street, where the police were surrounded by a crowd which allowed the gunmen and getaway driver to escape on foot.[9] The two were known to drink at the same establishment every Sunday morning and had been observed by IRA members doing so, allowing the attack to be planned well in advance.[10] Two of Bratty's cousins were also present at the attack but were not fired on.[11]

Reaction

In the short-term the killing of Elder was greeted with relief, even by some nationalist residents of the Lower Ormeau normally opposed to violence.[10] However, the aftermath saw three Catholics killed by the UDA in separate attacks with these sparking a series of IRA bomb attacks on loyalist bars, thus bringing about a temporary return to the spiral of tit-for-tat killing.[12] The killings of Bratty and Elder, along with that of Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) leader Ray Smallwoods earlier the same month, played a central role in delaying the Combined Loyalist Military Command (CLMC) ceasefire. The CLMC had been considering declaring a ceasefire following the shootings in Loughinisland, but reversed their decision after these three killings as they believed that any cessation of violence would have been seen by the IRA as a sign of weakness.[13] This was confirmed by the UDP's David Adams, who said the CLMC was ready to call a ceasefire in late June/early July 1994, although his party colleague Gary McMichael admitted the killings of Elder, Bratty and Smallwoods convinced him that an IRA ceasefire was near as he felt these were long-standing targets who were being killed before calling a halt to hostilities.[14]

Certain hardline elements with the UDA would later claim that Elder's killing had been sanctioned by members of the CLMC who were eager to see a ceasefire as Bratty had been an outspoken opponent of the initiative, although these allegations were never proven.[10] Pastor Kenny McClinton, a dissident former UDA gunman who was variously associated with the Ulster Independence Movement, the Loyalist Volunteer Force and the Orange Volunteers, even suggested in a pamphlet that Elder's killing had been arranged by the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP). This was part of a wider theme in McClinton's writing arguing that the PUP was a front for MI5 activity.[15]

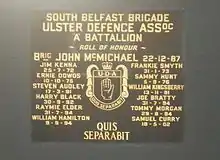

Elder and Bratty were commemorated in a wall plaque erected outside the Kimberley Bar. The pub, where the pair had been on the day they were killed, was known as a UDA stronghold in the area.[16] An August 2014 march commemorating the pair was condemned by both nationalist politicians and the Ulster Unionist Party after it ended with a ceremony in a Housing Executive-funded First World War garden of remembrance close to the Annadale Flats.[17][18]

Footnotes

- Cusack & McDonald, p. 224

- Cusack & McDonald, p. 184

- Lister & Jordan, p. 225

- "Sean Graham shooting: full report" (PDF).

- Lister & Jordan, p. 134

- Lister & Jordan, p. 117

- McDonald & Cusack, 2004, p. 238

- McDonald & Cusack, 2004, p. 255

- "IRA kills two in Belfast shooting". Independent report 1994. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- McDonald & Cusack, pp. 269–270

- "Cousins saw Loyalist boss gunned down". Daily Mirror – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . March 8, 1996. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- McDonald and Cusack 2004, pp. 259–70

- Taylor 2004, p. 231

- Wood 2006, p. 189

- McDonald and Cusack 2004, p. 283

- Wood 2006, pp. 288–89

- Fitzmaurice, Maurice (August 2, 2014). "WW1 Garden 'Has No Link to Terrorism'. Housing Executive Defends Its Funding". Daily Mirror – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- Kilpatrick, Chris (March 8, 1996). "'Disgrace' as UDA Accused of Hijacking Memorial to War Heroes; Residents' Fury at Plaque". Belfast Telegraph – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

References

Cusack, Jim & McDonald, Henry (1997). UVF. Dublin: Poolbeg. ISBN 1-85371-687-1.

Cusack, Jim & McDonald, Henry (2004). UDA: Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror. Dublin: Penguin Ireland. ISBN 1-84488-020-6.

Lister, David & Jordan, Hugh (2004). Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Edinburgh: Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-890-1.

Taylor, Peter (2000). Loyalists. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-4519-7.

Wood, Ian S. (2004). Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2427-9.