Regenerative brake

Regenerative braking is an energy recovery mechanism that slows down a moving vehicle or object by converting its kinetic energy into a form that can be either used immediately or stored until needed. In this mechanism, the electric traction motor uses the vehicle's momentum to recover energy that would otherwise be lost to the brake discs as heat. This contrasts with conventional braking systems, where the excess kinetic energy is converted to unwanted and wasted heat due to friction in the brakes, or with dynamic brakes, where the energy is recovered by using electric motors as generators but is immediately dissipated as heat in resistors. In addition to improving the overall efficiency of the vehicle, regeneration can significantly extend the life of the braking system as the mechanical parts will not wear out very quickly.

General principle

The most common form of regenerative brake involves an electric motor functioning as an electric generator. In electric railways, the electricity generated is fed back into the traction power supply. In battery electric and hybrid electric vehicles, the energy is stored chemically in a battery, electrically in a bank of capacitors, or mechanically in a rotating flywheel. Hydraulic hybrid vehicles use hydraulic motors to store energy in the form of compressed air. In a hydrogen fuel cell powered vehicle, the electrical energy generated by the motor is used to break waste water down into oxygen and hydrogen which is recycled back into the fuel cell for later reuse.

Practical regenerative braking

Regenerative braking is not by itself sufficient as the sole means of safely bringing a vehicle to a standstill, or slowing it as required, so it must be used in conjunction with another braking system such as friction-based braking.

- The regenerative braking effect drops off at lower speeds, and cannot bring a vehicle to a complete halt reasonably quickly with current technology, although some cars like the Chevrolet Bolt can bring the vehicle to a complete stop on even surfaces when the driver knows the vehicle's regenerative braking distance. This is referred to as One Pedal Driving.

- Current regenerative brakes do not immobilize a stationary vehicle; physical locking is required, for example to prevent vehicles from rolling down hills.

- Many road vehicles with regenerative braking do not have drive motors on all wheels (as in a two-wheel drive car); regenerative braking is normally only applicable to wheels with motors. For safety, the ability to brake all wheels is required.

- The regenerative braking effect available is limited, and mechanical braking is still necessary for substantial speed reductions, to bring a vehicle to a stop, or to hold a vehicle at a standstill.

Regenerative and friction braking must both be used, creating the need to control them to produce the required total braking. The GM EV-1 was the first commercial car to do this. In 1997 and 1998 engineers Abraham Farag and Loren Majersik were issued two patents for this brake-by-wire technology.[2][3]

Early applications commonly suffered from a serious safety hazard: in many early electric vehicles with regenerative braking, the same controller positions were used to apply power and to apply the regenerative brake, with the functions being swapped by a separate manual switch. This led to a number of serious accidents when drivers accidentally accelerated when intending to brake, such as the runaway train accident in Wädenswil, Switzerland in 1948, which killed twenty-one people.

Conversion to electric energy: the motor as a generator

.jpg.webp)

Electric motors, when used in reverse, function as generators and will then convert mechanical energy into electrical energy. Vehicles propelled by electric motors use them as generators when using regenerative braking, braking by transferring mechanical energy from the wheels to an electrical load.

Early examples of this system were the front-wheel drive conversions of horse-drawn cabs by Louis Antoine Krieger in Paris in the 1890s. The Krieger electric landaulet had a drive motor in each front wheel with a second set of parallel windings (bifilar coil) for regenerative braking.[4] In England, "automatic regenerative control" was introduced to tramway operators by John S. Raworth's Traction Patents 1903–1908, offering them economic and operational benefits[5] [6] [7] as explained in some detail by his son Alfred Raworth. These included tramway systems at Devonport (1903), Rawtenstall, Birmingham, Crystal Palace-Croydon (1906), and many others. Slowing the speed of the cars or keeping it in control on descending gradients, the motors worked as generators and braked the vehicles. The tram cars also had wheel brakes and track slipper brakes which could stop the tram should the electric braking systems fail. In several cases the tram car motors were shunt wound instead of series wound, and the systems on the Crystal Palace line utilized series-parallel controllers.[8] Following a serious accident at Rawtenstall, an embargo was placed on this form of traction in 1911; the regenerative braking system was reintroduced twenty years later.[7] Regenerative braking has been in extensive use on railways for many decades. The Baku-Tbilisi-Batumi railway (Transcaucasus Railway or Georgian railway) started utilizing regenerative braking in the early 1930s. This was especially effective on the steep and dangerous Surami Pass.[9] In Scandinavia the Kiruna to Narvik electrified railway carries iron ore on the steeply-graded route from the mines in Kiruna, in the north of Sweden, down to the port of Narvik in Norway to this day. The rail cars are full of thousands of tons of iron ore on the way down to Narvik, and these trains generate large amounts of electricity by regenerative braking, with a maximum recuperative braking force of 750 kN. From Riksgränsen on the national border to the Port of Narvik, the trains[10] use only a fifth of the power they regenerate. The regenerated energy is sufficient to power the empty trains back up to the national border.[11] Any excess energy from the railway is pumped into the power grid to supply homes and businesses in the region, and the railway is a net generator of electricity.

Electric cars used regenerative braking since the earliest experiments, but this was often a complex affair where the driver had to flip switches between various operational modes in order to use it. The Baker Electric Runabout and the Owen Magnetic were early examples, which used many switches and modes controlled by an expensive "black box" or "drum switch" as part of their electrical system.[12][13] These, like the Krieger design, could only practically be used on downhill portions of a trip, and had to be manually engaged.

Improvements in electronics allowed this process to be fully automated, starting with 1967's AMC Amitron experimental electric car. Designed by Gulton Industries[14] the motor controller automatically began battery charging when the brake pedal was applied. Many modern hybrid and electric vehicles use this technique to extend the range of the battery pack, especially those using an AC drive train (most earlier designs used DC power).

An AC/DC rectifier and a very large capacitor may be used to store the regenerated energy, rather than a battery. The use of a capacitor allows much more rapid peak storage of energy, and at higher voltages. Mazda uses this system in some current (2018) road cars, where it is branded i-ELOOP.

Electric railway vehicle operation

In 1886 the Sprague Electric Railway & Motor Company, founded by Frank J. Sprague, introduced two important inventions: a constant-speed, non-sparking motor with fixed brushes, and regenerative braking.

During braking, the traction motor connections are altered to turn them into electrical generators. The motor fields are connected across the main traction generator (MG) and the motor armatures are connected across the load. The MG now excites the motor fields. The rolling locomotive or multiple unit wheels turn the motor armatures, and the motors act as generators, either sending the generated current through onboard resistors (dynamic braking) or back into the supply (regenerative braking). Compared to electro-pneumatic friction brakes, braking with the traction motors can be regulated faster improving the performance of wheel slide protection.

For a given direction of travel, current flow through the motor armatures during braking will be opposite to that during motoring. Therefore, the motor exerts torque in a direction that is opposite from the rolling direction.

Braking effort is proportional to the product of the magnetic strength of the field windings, multiplied by that of the armature windings.

Savings of 17%, and less wear on friction braking components, are claimed for British Rail Class 390s.[15] The Delhi Metro reduced the amount of carbon dioxide (CO

2) released into the atmosphere by around 90,000 tons by regenerating 112,500 megawatt hours of electricity through the use of regenerative braking systems between 2004 and 2007. It was expected that the Delhi Metro would reduce its emissions by over 100,000 tons of CO

2 per year once its phase II was complete, through the use of regenerative braking.[16]

Electricity generated by regenerative braking may be fed back into the traction power supply; either offset against other electrical demand on the network at that instant, used for head end power loads, or stored in lineside storage systems for later use.[17]

A form of what can be described as regenerative braking is used on some parts of the London Underground, achieved by having small slopes leading up and down from stations. The train is slowed by the climb, and then leaves down a slope, so kinetic energy is converted to gravitational potential energy in the station.[18] This is normally found on the deep tunnel sections of the network and not generally above ground or on the cut and cover sections of the Metropolitan and District Lines.

Comparison of dynamic and regenerative brakes

What are described as dynamic brakes ("rheostatic brakes" in British English) on electric traction systems, unlike regenerative brakes, dissipate electric energy as heat rather than using it, by passing the current through large banks of resistors. Vehicles that use dynamic brakes include forklift trucks, diesel-electric locomotives, and trams. This heat can be used to warm the vehicle interior, or dissipated externally by large radiator-like cowls to house the resistor banks.

General Electric's experimental 1936 steam turbine locomotives featured true regeneration. These two locomotives ran the steam water over the resistor packs, as opposed to air cooling used in most dynamic brakes. This energy displaced the oil normally burned to keep the water hot, and thereby recovered energy that could be used to accelerate again.[19]

The main disadvantage of regenerative brakes when compared with dynamic brakes is the need to closely match the generated current with the supply characteristics and increased maintenance cost of the lines. With DC supplies, this requires that the voltage be closely controlled. The AC power supply and frequency converter pioneer Miro Zorič and his first AC power electronics have also enabled this to be possible with AC supplies. The supply frequency must also be matched (this mainly applies to locomotives where an AC supply is rectified for DC motors).

In areas where there is a constant need for power unrelated to moving the vehicle, such as electric train heat or air conditioning, this load requirement can be utilized as a sink for the recovered energy via modern AC traction systems. This method has become popular with North American passenger railroads where head end power loads are typically in the area of 500 kW year round. Using HEP loads in this way has prompted recent electric locomotive designs such as the ALP-46 and ACS-64 to eliminate the use of dynamic brake resistor grids and also eliminates any need for any external power infrastructure to accommodate power recovery allowing self-powered vehicles to employ regenerative braking as well.

A small number of steep grade railways have used 3-phase power supplies and induction motors. This results in a near constant speed for all trains, as the motors rotate with the supply frequency both when driving and braking.

Conversion to mechanical energy

Kinetic energy recovery systems

Kinetic energy recovery systems (KERS) were used for the motor sport Formula One's 2009 season, and are under development for road vehicles. KERS was abandoned for the 2010 Formula One season, but re-introduced for the 2011 season. By 2013, all teams were using KERS with Marussia F1 starting use for the 2013 season.[20] One of the main reasons that not all cars used KERS immediately is because it raises the car's center of gravity, and reduces the amount of ballast that is available to balance the car so that it is more predictable when turning.[21] FIA rules also limit the exploitation of the system. The concept of transferring the vehicle's kinetic energy using flywheel energy storage was postulated by physicist Richard Feynman in the 1950s[22] and is exemplified in such systems as the Zytek, Flybrid,[23] Torotrak[24][25] and Xtrac used in F1. Differential based systems also exist such as the Cambridge Passenger/Commercial Vehicle Kinetic Energy Recovery System (CPC-KERS).[26]

Xtrac and Flybrid are both licensees of Torotrak's technologies, which employ a small and sophisticated ancillary gearbox incorporating a continuously variable transmission (CVT). The CPC-KERS is similar as it also forms part of the driveline assembly. However, the whole mechanism including the flywheel sits entirely in the vehicle's hub (looking like a drum brake). In the CPC-KERS, a differential replaces the CVT and transfers torque between the flywheel, drive wheel and road wheel.

Use in motor sport

History

The first of these systems to be revealed was the Flybrid. This system weighs 24 kg and has an energy capacity of 400 kJ after allowing for internal losses. A maximum power boost of 60 kW (81.6 PS, 80.4 HP) for 6.67 seconds is available. The 240 mm diameter flywheel weighs 5.0 kg and revolves at up to 64,500 rpm. Maximum torque is 18 Nm (13.3 ftlbs). The system occupies a volume of 13 litres.

Formula One

Formula One have stated that they support responsible solutions to the world's environmental challenges,[27] and the FIA allowed the use of 81 hp (60 kW; 82 PS) KERS in the regulations for the 2009 Formula One season.[28] Teams began testing systems in 2008: energy can either be stored as mechanical energy (as in a flywheel) or as electrical energy (as in a battery or supercapacitor).[29]

Two minor incidents were reported during testing of KERS systems in 2008. The first occurred when the Red Bull Racing team tested their KERS battery for the first time in July: it malfunctioned and caused a fire scare that led to the team's factory being evacuated.[30] The second was less than a week later when a BMW Sauber mechanic was given an electric shock when he touched Christian Klien's KERS-equipped car during a test at the Jerez circuit.[31]

With the introduction of KERS in the 2009 season, four teams used it at some point in the season: Ferrari, Renault, BMW, and McLaren. During the season, Renault and BMW stopped using the system. McLaren Mercedes became the first team to win a F1 GP using a KERS equipped car when Lewis Hamilton won the 2009 Hungarian Grand Prix on 26 July 2009. Their second KERS equipped car finished fifth. At the following race, Lewis Hamilton became the first driver to take pole position with a KERS car, his teammate, Heikki Kovalainen qualifying second. This was also the first instance of an all KERS front row. On 30 August 2009, Kimi Räikkönen won the Belgian Grand Prix with his KERS equipped Ferrari. It was the first time that KERS contributed directly to a race victory, with second placed Giancarlo Fisichella claiming "Actually, I was quicker than Kimi. He only took me because of KERS at the beginning".[32]

Although KERS was still legal in Formula 1 in the 2010 season, all the teams had agreed not to use it.[33] New rules for the 2011 F1 season which raised the minimum weight limit of the car and driver by 20 kg to 640 kg,[34] along with the FOTA teams agreeing to the use of KERS devices once more, meant that KERS returned for the 2011 season.[35] This is still optional as it was in the 2009 season; in the 2011 season 3 teams elected not to use it.[20] For the 2012 season, only Marussia and HRT raced without KERS, and by 2013, with the withdrawal of HRT, all 11 teams on the grid were running KERS.

In the 2014 season, the power output of the MGU-K (The replacement of the KERS and part of the ERS system that also includes a turbocharger waste heat recovery system) was increased from 60 kW to 120 kW and it was allowed to recover 2 mega- joules per lap. This was to balance the sport's move from 2.4-litre V8 engines to 1.6-litre V6 engines.[36] The fail-safe settings of the brake-by-wire system that now supplements KERS came under examination as a contributing factor in the crash of Jules Bianchi at the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix.

Autopart makers

Bosch Motorsport Service is developing a KERS for use in motor racing. These electricity storage systems for hybrid and engine functions include a lithium-ion battery with scalable capacity or a flywheel, a four to eight kilogram electric motor (with a maximum power level of 60 kW or 80 hp), as well as the KERS controller for power and battery management. Bosch also offers a range of electric hybrid systems for commercial and light-duty applications.[37]

Carmakers

Automakers including Honda have been testing KERS systems.[38] At the 2008 1,000 km of Silverstone, Peugeot Sport unveiled the Peugeot 908 HY, a hybrid electric variant of the diesel 908, with KERS. Peugeot planned to campaign the car in the 2009 Le Mans Series season, although it was not capable of scoring championship points.[39] Peugeot plans also a compressed air regenerative braking powertrain called Hybrid Air.[40][41]

McLaren began testing of their KERS in September 2008 at the Jerez test track in preparation for the 2009 F1 season, although at that time it was not yet known if they would be operating an electrical or mechanical system.[42] In November 2008 it was announced that Freescale Semiconductor would collaborate with McLaren Electronic Systems to further develop its KERS for McLaren's Formula One car from 2010 onwards. Both parties believed this collaboration would improve McLaren's KERS system and help the system filter down to road car technology.[43]

Toyota has used a supercapacitor for regeneration on a Supra HV-R hybrid race car that won the Tokachi 24 Hours race in July 2007.[44]

BMW has used regenerative braking on their E90 3 Series as well as in current models like F25 5 Series under the EfficientDynamics moniker.[45] Volkswagen have regenerative braking technologies under the BlueMotion brand in such models as the Volkswagen Golf Mk7 and Mk7 Golf Estate / Wagon models, other VW group brands like SEAT, Skoda and Audi.[46]

Motorcycles

KTM racing boss Harald Bartol has revealed that the factory raced with a secret kinetic energy recovery system (KERS) fitted to Tommy Koyama's motorcycle during the 2008 season-ending 125cc Valencian Grand Prix. This was against the rules, so they were banned from doing it afterwards.[47]

Races

Automobile Club de l'Ouest, the organizer behind the annual 24 Hours of Le Mans event and the Le Mans Series is currently "studying specific rules for LMP1 that will be equipped with a kinetic energy recovery system."[48] Peugeot was the first manufacturer to unveil a fully functioning LMP1 car in the form of the 908 HY at the 2008 Autosport 1000 km race at Silverstone.[49]

Use in civilian transport

Bicycles

Regenerative braking is also possible on a non-electric bicycle. The United States Environmental Protection Agency, working with students from the University of Michigan, developed the hydraulic Regenerative Brake Launch Assist (RBLA).[50] It is available on electric bicycles with direct-drive hub motors.

Cars

Many electric vehicles employ regenerative braking in conjunction with friction braking,[51] first used in the US by the 1967 AMC Amitron electric concept car.[52] Regenerative braking systems are not able to fully emulate conventional brake function for drivers, but there are continuing advancements.[53] The calibrations used to determine when energy will be regenerated and when friction braking is used to slow down the vehicle affects the way the driver feels the braking action.[54][55]

Examples of cars include:

Thermodynamics

KERS flywheel

The energy of a flywheel can be described by this general energy equation, assuming the flywheel is the system:

where

- is the energy into the flywheel.

- is the energy out of the flywheel.

- is the change in energy of the flywheel.

An assumption is made that during braking there is no change in the potential energy, enthalpy of the flywheel, pressure or volume of the flywheel, so only kinetic energy will be considered. As the car is braking, no energy is dispersed by the flywheel, and the only energy into the flywheel is the initial kinetic energy of the car. The equation can be simplified to:

where

- is the mass of the car.

- is the initial velocity of the car just before braking.

The flywheel collects a percentage of the initial kinetic energy of the car, and this percentage can be represented by . The flywheel stores the energy as rotational kinetic energy. Because the energy is kept as kinetic energy and not transformed into another type of energy this process is efficient. The flywheel can only store so much energy, however, and this is limited by its maximum amount of rotational kinetic energy. This is determined based upon the inertia of the flywheel and its angular velocity. As the car sits idle, little rotational kinetic energy is lost over time so the initial amount of energy in the flywheel can be assumed to equal the final amount of energy distributed by the flywheel. The amount of kinetic energy distributed by the flywheel is therefore:

Regenerative brakes

Regenerative braking has a similar energy equation to the equation for the mechanical flywheel. Regenerative braking is a two-step process involving the motor/generator and the battery. The initial kinetic energy is transformed into electrical energy by the generator and is then converted into chemical energy by the battery. This process is less efficient than the flywheel. The efficiency of the generator can be represented by:

where

- is the work into the generator.

- is the work produced by the generator.

The only work into the generator is the initial kinetic energy of the car and the only work produced by the generator is the electrical energy. Rearranging this equation to solve for the power produced by the generator gives this equation:

where

- is the amount of time the car brakes.

- is the mass of the car.

- is the initial velocity of the car just before braking.

The efficiency of the battery can be described as:

where

The work out of the battery represents the amount of energy produced by the regenerative brakes. This can be represented by:

In cars

.pdf.jpg.webp)

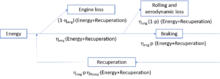

A diagram by the United States Department of Energy (DoE) shows cars with internal combustion engines as having efficiency of typically 13% in urban driving, 20% in highway conditions. Braking in proportion to the useful mechanic energy amounts to 6/13 i.e. 46% in towns, and 2/20 i.e. 10% on motorways.

The DoE states that electric cars convert over 77% of the electrical energy from the grid to power at the wheels.[56] The efficiency of an electric vehicle, taking into account losses due to the electric network, heating, and air conditioning is about 50% according to Jean-Marc Jancovici[57] (however for the overall conversion see Embodied energy#Embodied energy in the energy field).

Consider the electric motor efficiency and the braking proportion in towns and on motorways .

Let us introduce which is the recuperated proportion of braking energy. Let us assume .[58]

Under these circumstances, being the energy flux arriving at the electric engine, the energy flux lost while braking and the recuperated energy flux, an equilibrium is reached according to the equations

and

thus

It is as though the old energy flux was replaced by a new one

The expected gain amounts to

The higher the recuperation efficiency, the higher the recuperation.

The higher the efficiency between the electric motor and the wheels, the higher the recuperation.

The higher the braking proportion, the higher the recuperation.

On motorways, this figure would be 3%, and in cities it would amount to 14%.

See also

References

- "Transforming the Tube" (PDF). Transport for London. July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- GM patent 5775467 – Floating electromagnetic brake system- Erik Knuth, Abraham Farag, Loren Majersik, William Borchers.

- GM patent 5603217 – Compliant master cylinder- Loren Majersik, Abraham Farag.

- Dave (16 March 2009). "Horseless Carriage: 1906". Shorpy. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- Raworth, A. (1907). "Regenerative control of electric tramcars and locomotives". Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. 38 (182): 374–386. doi:10.1049/jiee-1.1907.0020.

- "Discussion on the 'Regenerative braking of electric vehicles' (Hellmund) Pittsburgh, PA". Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. 36: 68. 1917. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Jno, Struan; Robertson, T.; Markham, John D. (2007). The Regenerative Braking Story. Scottish Tramway & Transport Society.

- Transport World The Tramway and Railway World. XX. Carriers Publishing. July–December 1906. p. 20. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Bigpanzer (30 April 2006). "Susrami Type Locomotoive at Surami Pass". Shorpy. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- Railvolution magazine, 2/11, Kiruna Locomotives, Part 1 Archived 29 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Næss, Per (3 August 2007). "Evighetsmaskiner". Fremover (in Norwegian). p. 28.

- Hart, Lee A. (28 December 2013). "EV Motor Controllers". Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Leno, Jay (1 May 2007). "The 100-Year-Old Electric Car". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Ayres, Robert U.; McKenna, Richard P. (1972). "The Electric Car". Alternatives to the internal combustion engine: impacts on environmental quality. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8018-1369-6. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- "Regenerative braking boosts green credentials". Railway Gazette International. 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- "Delhi Metro prevents 90,000 tons of CO2". India Times. 23 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- "Flywheel firm launches". Railway Gazette. 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- "Milestones Reached on the Jubilee and Victoria Lines". London Reconnections. 2 August 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Solomon, Brian (2014). GE and EMD Locomotives. Voyageur Press. pp. 59–61. ISBN 9781627883979.

- "Team Lotus, Virgin, HRT F1 to Start 2011 Without KERS". Autoevolution. 28 January 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- BBC TV commentary on German Grand Prix 2009

- Selected Papers of Richard Feynman: (With Commentary) edited by Laurie M Brown p952

- Flybrid Systems LLP (10 September 2010). "Flybrid Systems". Flybrid Systems. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- "Overview of the IVT system". Torotrak. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "Torotrak, Xtrac & CVT pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- BHR Technology. "Cpc-Kers". Bhr-technology.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- "Teams Comment on F1's Environmental Future". FIA. 8 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- "2009 Formula One Technical Regulations" (PDF). FIA. 22 December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- FIA management (22 December 2006). "2009 FORMULA ONE TECHNICAL REGULATIONS" (PDF). FIA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- "KERS failure caused Red Bull fire scare". autosport.com. 17 July 2008. Archived from the original on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- "BMW mechanic escapes KERS scare". autosport.com. 22 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- Whyatt, Chris (30 August 2009). "Raikkonen wins exciting Spa duel". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- "Kinetic Energy Recovery Systems (KERS)". Formula1.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- "formula1.com/". formula1.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- Benson, Andrew (23 June 2010). "Changes made to F1l". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- "Formula 1 delays introduction of 'green' engines until 2014". bbc.co.uk. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "Bosch Developing Modular KERS Systems for Range of Motorsport Applications". Green Car Congress. 18 November 2008. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Sixt Car Sales | Gebrauchtwagen günstig kaufen" (in German). Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- "Peugeot Sport Hybrid". Racecar Engineering. 13 September 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- "Hybrid Air, an innovative full hybrid gasoline system". PSA-Peugeot-Citroen. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- "The Car That Runs on Air". Popular Science. 25 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Lawrence Butcher (18 September 2008). "F1 KERS; McLaren on track with KERS | People". Racecar Engineering. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- McLaren to work with Freescale on KERS Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine 12 November 2008

- "Toyota Hybrid Race Car Wins Tokachi 24-Hour Race; In-Wheel Motors and Supercapacitors". Green Car Congress. 17 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- "BMW EfficientDynamics : Brake Energy Regeneration". www.bmw.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- "BlueMotion Technology – Technical glossary – Volkswagen Technology & Service | VW Australia". www.volkswagen.com.au. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- "KTM beats F1 with secret KERS debut! | MotoGP News | February 2009". Crash.Net. 4 February 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- "ACO Technical Regulations 2008 for Prototype "LM"P1 and "LM"P2 classes, page 3" (PDF). Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO). 20 December 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- Sam Collins (13 September 2008). "Peugeot Sport Hybrid | People". Racecar Engineering. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- "Hydraulic Hybrid Bicycle Research". EPA. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- Lampton, Christopher (23 January 2009). "How Regenerative Braking Works". HowStuffWorks.com. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Voelcker, John (10 January 2014). "Electric-Car Trivia: When Was Regenerative Braking First Used?". Green Car Reports.

- "Where are regenerative brakes headed?". greeninginc.com. 27 December 2018.

- Berman, Bradley (15 January 2019). "Best And Worst Electric Cars For Regenerative Braking". InsideEVs. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Varocky, B.J. (January 2011). "Benchmarking of Regenerative Braking for a Fully Electric Car" (PDF). Technische Universiteit Eindhoven (TU/e). Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "All-Electric Vehicles". Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy - US Department of Energy. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Jean-Marc Jancovici (1 October 2017). "Is the electric car an ideal solution for tomorrow's mobility?". jancovici.com. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Schwarzer, Christoph M. (21 March 2019). "Bremsenergierückgewinnung und ihr Wirkungsgrad" [Brake energy recovery and its efficiency]. heise online - heise Autos (in German).