Religion in Berlin

More than 60 percent of Berlin residents have no registered religious affiliation. As of 2010, at least 30 percent of the population identified with some form of Christianity (18.7 percent Protestants, 9.1 percent Catholics and 2.7 percent other Christian), approximately 8.1 percent were Muslim, 1 percent were Jewish, and 1 percent belonged to other religions.[2] As of 2018, the number of registered church members has shrunk to 14.9 percent for EKD Protestants and 8.5 percent for Catholics.[1]

Irreligion

As of April 2009, 64 percent of Berlin residents have no registered religious affiliation. For this reason, Berlin is sometimes called the "atheist capital of Europe".[3]

On 26 April 2009, a referendum (de) was held on whether Berlin pupils should be allowed to choose between the ethics class, a compulsory class introduced in all Berlin schools in 2006, and a religion class.[4] The SPD, the Left Party and Greens supported the "Pro Ethics" camp for a "No" vote, stressing that the ethics class should remain compulsory, and pupils could voluntarily take an extra religion class alongside it if they so chose; the CDU and FDP supported the "Pro Reli" camp for a "Yes" vote, wanting to give pupils a free choice.[4] In East Berlin, an overwhelming majority voted against the introduction of religious education.[4] In total, 51.5 percent voted "No" and 48.4 percent voted "Yes".[4]

There are a number of humanist groups in the city. The Humanistischer Verband Deutschlands (English: Humanist Association of Germany) is an organization to promote and spread a secular humanist worldview and an advocate for the rights of nonreligious people. It was founded 1993 in Berlin, and in 2009 according to the group it counted about 4100 members in the city.[5]

Christianity

Evangelical Church

The largest denominations as of 2010 are the Protestant regional church body of the Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia (EKBO), a united church comprising mostly Lutheran, a few Reformed and United Protestant congregations. EKBO is a member of both the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) and Union Evangelischer Kirchen (UEK) claiming 18.7 percent of the city's population.[2]

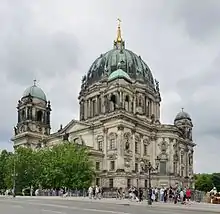

Since 2010 the leader of the church is bishop Dr. Markus Dröge (2010). St. Mary's Church, Berlin, is the church of the bishop of the EKBO with the Berlin Cathedral being under joint supervision of all the member churches of the UEK.

Roman Catholic Church

_1.jpg.webp)

In 1994, Pope John Paul II elevated Berlin to the rank of an archdiocese, supervising since the simultaneously erected Diocese of Görlitz (formerly Apostolic Administration) and the prior exempt Diocese of Dresden-Meißen.

As of 2004 the archdiocese has 386,279 Catholics out of the population of Berlin, most of Brandenburg (except of its southeastern corner, historical Lower Lusatia) and Hither Pomerania, i. e. the German part of Pomerania. This means that a little over 6 percent of the population in this area is Roman Catholic. There are 122 parishes in the archdiocese.

The Roman Catholic Church claims 9.1 percent of the city's registered members in 2010.[2] Berlin is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Berlin covering the northeast of Germany.

The current archbishop is Archbishop Heiner Koch, formerly Bishop of Dresden, who was appointed by Pope Francis on Monday, 8 June 2015, to replace the former archbishop, Cardinal Rainer Maria Woelki.

Orthodox Church

About 2.7 percent of the population identify with other Christian denominations, mostly Eastern Orthodox.[6] Berlin is also the seat of Orthodox cathedrals, such as the Cathedral of St. Boris the Baptist, one of the two seats of the Bulgarian Orthodox Diocese of Western and Central Europe, and the Resurrection of Christ Cathedral of the Diocese of Berlin (Patriarchate of Moscow).

Islam

In 2009, Islamic religious organizations in Berlin reported 249,000 members.[7] As of the end of 2015, 352,667 officially registered residents of Berlin had immigrated after 1955 from Arabic and Islamic countries, the largest part from Turkey, or were children of such immigrants.[8]

The Berlin Mosque (German: Berliner Moschee, Wilmersdorfer Moschee, Ahmadiyya Moschee) in Berlin is Germany's oldest mosque in use, situated on Brienner Straße 7-8 in Berlin-Wilmersdorf. It was designed by K. A. Hermann and was built between 1923 and 1925. Berlin Mosque, which has two 90 feet (27 m) tall minarets.

The Sehitlik Mosque in Neukölln built in 1983 serves as a cultural center as well as a place of worship. It can hold up to 1,500 people, and is the largest Islamic mosque in Berlin.[9]

Judaism

Of the estimated population of 30,000-45,000 Jewish residents in 2014,[11] approximately 12,000 are registered members of religious organizations.[6] Berlin is considered to have one of the rapidly growing Jewish communities in the world due to Russian, Eastern European, Israeli and German Jewish immigrants.[12][13]

The Centrum Judaicum and several synagogues—including the largest in Germany—have been renovated and reopened in 2007.[14] Berlin's annual week of Jewish culture and the Jewish Cultural Festival in Berlin, held for the 21st time in the same year, featuring concerts, exhibitions, public readings and discussions partially explain why Rabbi Yitzhak Ehrenberg of the orthodox Jewish community in Berlin states: "Orthodox Jewish life is alive in Berlin again." [15][16]

The Neue Synagoge ("New Synagogue") was built 1859–1866 as the main synagogue of the Berlin Jewish community, on Oranienburger Straße. Because of its refined Moorish style and resemblance to the Alhambra, it became an important architectural monument of the second half of the 19th century in the city.

Buddhism

In 1924 Dr. Paul Dahlke established the first German Buddhist monastery, the "Das Buddhistische Haus" in Reinickendorf. It is considered to be the oldest and largest Theravada Buddhist center in Europe and has been declared a National Heritage site.[17]

Places of worship

There are many places of worship in Berlin for the variety of religions and denominations. For example, there are 36 Baptist congregations (within Union of Evangelical Free Church Congregations in Germany), 29 New Apostolic Churches, 15 United Methodist churches, eight Free Evangelical Congregations, four Churches of Christ, Scientist (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 11th), six congregations of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), an Old Catholic church and even an Anglican church. The Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church has eight parishes of different sizes in Berlin.[18] Berlin has more than 80 mosques,[19] as well as two Buddhist temples.

Interfaith initiatives

Over the past years, Berlin has seen a considerable increase in interfaith initiatives, including the House of One project which looks at building a joint place of worship for adherents to different religions. In 2016, Berlin celebrated its first ever Interfaith Music Festival ("Festival der Religionen") which was organised by the international non-profit initiative Faiths In Tune and made possible with funds from the Berlin Lottery Foundation.

The Festival der Religionen combined live music and dance performances by artists from 13 different religions, an interfaith fair and several exhibitions on faith subjects.[20][21][22]

See also

References

- Statistischer Bericht Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner im Land Berlin am 31. Dezember 2018 (PDF). Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg. Abgerufen am 22. Februar 2020.

- Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland: Kirchenmitgliederzahlen am 31. Dezember 2010. EKD, 2011, (PDF; 0,45 MB) Retrieved, 10 March 2012.

- Connolly, Kate (26 April 2009). "Atheist Berlin to decide on religion's place in its schools". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- Antoine Verbij (27 April 2009). "Berlijn blijft een heidense stad". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Wer sind die Humanisten?". Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Amt für Statistik Berlin Brandenburg: Die kleine Berlin-Statistik 2010. (PDF-Datei Archived 4 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine). Retrieved, 4 January 2011.

- "Die kleine Berlin-Statistik 2015" (PDF). Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). December 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner im Land Berlin am 31. Dezember 2015" [Residents of the State of Berlin as of 31 December 2015] (PDF). Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). March 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Sehitlik Mosque Berlin - Germany". Beautiful Mosques. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "Epicenter of Holocaust Now Fastest-growing Jewish Community". Haaretz. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Ross, Mike (1 November 2014). "In Germany, a Jewish community now thrives". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- JEWS IN BERLIN? www.berlin-judentum.de. 16 August 2016.

- Germany: Berlin Facing Challenge Of Assimilating Russian-Speaking Jews. Radio Free Europe. 6 September 2012.

- "World | Europe | Major German synagogue reopened". BBC News. 31 August 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- Die Bundesregierung (Federal government of Germany): "Germany's largest synagogue officially reopened. Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine" 31 August 2007

- Axelrod, Toby. "Cantor who led Berlin's Jews for past 50 years dies." j.. 21 January 2000

- "80th anniversary of Das Buddhistische Haus in Berlin – Frohnau, Germany". Daily News (Sri Lanka). 24 April 2004. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "Lutheran Diocese Berlin-Brandenburg". Selbständige Evangelisch-Lutherische Kirche. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "Berlin′s mosques". Deutsche Welle. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- "FAITHS IN TUNE Interfaith Music Festival". FAITHS IN TUNE Interfaith Music Festival. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "Public Praying in Berlin". www.tagesspiegel.de. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Lombard, Jerome (14 July 2016). "Glauben im Einklang: Das Festival der Religionen will durch Musik Respekt und Dialog fördern". Retrieved 2 August 2016 – via Jüdische Allgemeine.