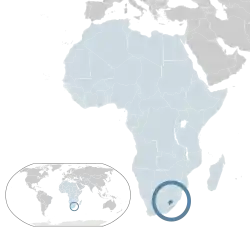

Religion in Lesotho

Christianity is the dominant religion in Lesotho,[2] which is estimated to be more than 95 per cent Christian.[3][2][4] Non-Christian religions represent only 1.5% of the population, and those of no religion 3.5%.[5] The non-Christian people primarily subscribe to traditional African religions, with an insignificant (< 0.2%) minor presence of Islam, Judaism and Asian religions.[6]

Religion in Lesotho (Association of Religion Data Archives 2015)[1]

Christianity

Catholics account for 49.4 per cent of the population while Protestants represent 40 percent (Anglicans 5.3 per cent, Pentecostals 15.4 per cent, other Protestants 18.2% and other Christians an additional 1.8 per cent).[1] The Roman Catholic population is served by the province of the Metropolitan Archbishop of Maseru and his three suffragans (the bishops of Leribe, Mohale's Hoek and Qacha's Nek), who also form the national episcopal conference.

Christianity arrived in Lesotho from French missions at the invitation of King Moshoeshoe I in 1830s.[7] While King Moshoeshoe I invited Christian missionaries, he retained his traditional religion and divorced two of his wives who had converted to Christianity.[7] Initial reports of French evangelist missionaries alleged cannibalism as a part of Lesotho traditional religion. Later missionaries such as Henry Callaway, as well as anthropologists, consider those initial reports as unreliable and mythical, rather than historical or true representation of the traditional religion of the Lesotho people.[8]

The first Catholic mission started in 1863. It was called Motse-oa-'M'a-Jesu, and led by Bishop Allard. He invited Holy Family Sisters from France to work with Sotho women. The initial efforts aimed at the gaining converts as well as ending the practice of polygyny where old men paid brideprice to marry young girls. The later efforts attracted resistance from the traditional families. According to Allard's memoirs, Sotho women converted to Catholicism in larger numbers earlier than Sotho men.[9]

The two Christian denominations have historic links to two major political parties in Lesotho. The Evangelicals have been aligned with the Basotho Congress Party, while the Roman Catholic Church has supported the Basotho National Party.[4] The Pronuncio from Pretoria represents the Holy See in the Lesotho government.[4]

Traditional religion

The traditional Sotho religion is traceable with archaeological evidence to around the 10th century. They share themes with the Tswana traditional religion. The Chief of a Sotho community was also their spiritual leader. Ancestor spirits called Badimo worship practices were a significant part of the Sotho community, along with rituals such as rainmaking dance. The Sotho had developed the concept of Modimo, the Supreme Being. The Modimo, in Sotho theology, created lesser deities with powers to interact with human beings.[10]

Religious rights

The Lesotho constitution protects the freedom of religion, a right that has been broadly and generally respected by the Lesotho Government.[2]

See also

- Anglican Diocese of Lesotho

- Christian Council of Lesotho

- Islam in Lesotho

- Roman Catholicism in Lesotho

References

- "Lesotho". Association of Religion Data Archives. 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Lesotho. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Table: Christian Population as Percentages of Total Population by Country". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Elias Kifon Bongmba (2015). Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa. Routledge. pp. 393–394. ISBN 978-1-134-50577-7.

- "Lesotho: Demographic and Health Survey, 2014" (PDF). Ministry of Health. p. 38. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Lesotho, CIA Factbook

- Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 699. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- David Chidester (1997). African Traditional Religion in South Africa: An Annotated Bibliography. ABC-CLIO. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-313-30474-3.

- Richard Elphick (1997). Christianity in South Africa: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. University of California Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0-520-20940-4.

- Toyin Falola; Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. pp. 644–645. ISBN 978-1-59884-666-9.