Religion in the Philippines

Religion in the Philippines is marked by a majority of people being adherents of the Christian faith.[2] At least 92% of the population is Christian; about 81% belong to the Catholic Church while about 11% belong to Protestantism, Orthodoxy, Restorationist and Independent Catholicism and other denominations such as Iglesia Filipina Independiente, Iglesia ni Cristo, Seventh-day Adventist Church, United Church of Christ in the Philippines, Members Church of God International (MCGI) and Evangelicals.[2] Officially, the Philippines is a secular nation, with the Constitution guaranteeing separation of church and state, and requiring the government to respect all religious beliefs equally.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

According to national religious surveys, about 5.6% of the population of the Philippines is Muslim, making Islam the second largest religion in the country. However, A 2012 estimate by the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF) stated that there were 10.7 million Muslims, or approximately 11 percent of the total population.[3] The majority of Muslims live in parts of Mindanao, Palawan, and the Sulu Archipelago – an area known as Bangsamoro or the Moro region.[4] Some have migrated into urban and rural areas in different parts of the country. Most Muslim Filipinos practice Sunni Islam according to the Shafi'i school.[5] There are some Ahmadiyya Muslims in the country.[6]

Indigenous Philippine folk religions (collectively referred to as Anitism or Bathalism), the traditional religion of Filipinos which predates Philippine Christianity and Islam, is practiced by an estimated 2% of the population,[7][8] made up of many indigenous peoples, tribal groups, and people who have reverted into traditional religions from Catholic/Christian or Islamic religions. These religions are often syncretized with Christianity and Islam. Buddhism is practiced by 2% of the populations by the Japanese-Filipino community,[9][7][8][10] and together with Taoism and Chinese folk religion is also dominant in Chinese communities. There are also smaller number of followers of Sikhism, Hinduism as well.[7][8][10][11][12] More than 10% of the population is non-religious, with the percentage of non-religious people overlapping with various faiths, as the vast majority of the non-religious select a religion in the Census for nominal purposes.[7][8][13]

According to the 2010 census, Evangelicals comprised 2% of the population. It is particularly strong among American and Korean communities, Northern Luzon especially in Cordillera Administrative Region, Southern Mindanao[14] and many other tribal groups in the Philippines. Protestants both mainline and evangelical have gained significant annual growth rate up to 10% since 1910 to 2015.[15]

Demographics

The Philippine Statistics Authority reported in October 2015 that, based on the 2010 census, 80.58% of the total Filipino population were Catholics, 10.8% were Protestant and 5.57% were Muslims.[16]

| Affiliation | Number (2010) | Number (2015) |

|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic, including Catholic Charismatic | 74,211,896 | 80,304,061 |

| Islam | 5,127,084 | 6,064,744 |

| Evangelicals (PCEC) | 2,469,957 | 2,445,113 |

| Iglesia ni Cristo | 2,251,941 | 2,664,498 |

| Non-Roman Catholic and Protestant (NCCP) | 1,071,686 | 1,146,954 |

| Aglipayan | 916,639 | 756,225 |

| Seventh-day Adventist | 681,216 | 791,552 |

| Bible Baptist Church | 480,409 | 553,790 |

| United Church of Christ in the Philippines | 449,028 | 419,017 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 410,957 | 438,148 |

| None | 73,248 | 19,953 |

| Others/Not reported | 3,953,917 | 5,375,248 |

| Total | 92,097,978 | 100,979,303 |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[17] | ||

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

Christianity

Christianity arrived in the Philippines with the landing of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. In 1543, Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos named the archipelago Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip II of Spain, who was then Prince of Girona and of Asturias under his father, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor who, as Charles I, was also King of Spain. Missionary activity during the country's colonial rule by Spain and the United States led the transformation of the Philippines into the first and then, along with East Timor, one of two predominantly Catholic nations in East Asia, with approximately 92.5% of the population belonging to the Christian faith.[7][18]

Catholicism

Catholicism (Filipino: Katolisismo; Spanish: Catolicismo) is the predominant religion and the largest Christian denomination, with estimates of approximately 80.6% of the population belonging to this faith in the Philippines.[19] Spanish efforts to convert many on the islands were aided by the lack of a significant central authority, and by friars who learnt local languages to preach. Some traditional animistic practices blended with the new faith.[20]

The Catholic Church has great influence on Philippine society and politics. One typical event is the role of the Catholic hierarchy during the bloodless People Power Revolution of 1986. Then-Archbishop of Manila and de facto Primate of the Philippines, Jaime Cardinal Sin appealed to the public via radio to congregate along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue in support of rebel forces. Some seven million people responded to the call between February 22–25, and the non-violent protests successfully forced President Ferdinand E. Marcos out of power and into exile in Hawaii.

Several Catholic holidays are culturally important as family occasions, and are observed in the civil calendar. Chief among these are Christmas, which includes celebrations of the civil New Year, and the more solemn Holy Week, which may occur in March or April. Every November, Filipino families celebrate All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day as a single holiday in honour of the saints and the dead, visiting and cleaning ancestral graves, offering prayers, and feasting. As of 2018, Feast of the Immaculate Conception on December 8 was added as a special non-working holiday.[21]

Census data from 2010 found that about 80.58% of the population professed Catholicism.[16]

Papal visits

- Pope Paul VI was the target of an assassination attempt at Manila International Airport in the Philippines in 1970. The assailant, a Bolivian Surrealist painter named Benjamín Mendoza y Amor Flores, lunged toward Pope Paul with a kris, but was subdued.

- Pope John Paul II visited the country twice, 1981 and 1995. The final Mass of the event was recorded to have been attended by 5 million people, and was at the time the largest papal crowd in history.

- Pope Benedict XVI declined the invitation of Cardinal Gaudencio Rosales and CBCP President Ángel Lagdameo to visit because of a hectic schedule.

- Pope Francis visited the country in January 2015, and the concluding Mass at the Quirino Grandstand had an estimated 7 million attendees, breaking the record at Pope John Paul's Mass at the same site twenty years prior.

Philippine Independent Church

.jpg.webp)

The Philippine Independent Church (officially Spanish: Iglesia Filipina Independiente, IFI; colloquially known as the Aglipayan Church) is an independent Christian denomination in the form of a national church in the Philippines. Its schism from the Catholic Church was proclaimed in 1902 by the members of the Unión Obrera Democrática Filipina due to the mistreatment of Filipinos by Spanish priests and the execution of nationalist José Rizal under Spanish colonial rule.

Isabelo de los Reyes was one of the initiators of the separation, and suggested that former Catholic priest Gregorio Aglipay be the head of the church. It is also known as the Aglipayan Church after its first Obispo Maximo, Gregorio Aglipay.

Commonly shared beliefs in the Aglipayan Church are the rejection of the Apostolic Succession solely to the Petrine Papacy, the acceptance of priestly ordination of women, the free option of clerical celibacy, the tolerance to join Freemasonry groups, non-committal in belief regarding transubstantiation and Real Presence of the Eucharist, and the advocacy of contraception and same-sex civil rights among its members. Many saints canonised by Rome after the schism are also not officially recognised by the Aglipayan church and its members.

Today, Aglipayans in the Philippines claim to number at least 6 to 8 million members, with most from the northern part of Luzon, especially in the Ilocos Region and in the parts of Visayas like Antique, Iloilo and Guimaras provinces. Congregations are also found throughout the Philippine diaspora in North America, Europe, Middle East and Asia. The church is the second-largest single Christian denomination in the country after the Catholic Church (some 80.2% of the population), comprising about 6.7% of the total population of the Philippines. By contrast, the 2010 Philippine census recorded only 916,639 members in the country, or about 1% of the population. It has 47 dioceses including the dioceses outside the Philippines such the Diocese of Tampa (USA) and the Diocese Western USA and Canada. It has Fellowship congregations in the United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates, Hongkong and Singapore. IFI is in full communion with the Anglican Churches and the Episcopal Church.

In 2010 the Philippine Independent Church had around 138,364 adherents.[16]

Iglesia ni Cristo

(2018-02-07).jpg.webp)

Iglesia ni Cristo (English: Church of Christ; Spanish: Iglesia de Cristo) is the largest entirely indigenous-initiated religious organisation in the Philippines comprising roughly 1.5% of religious affiliation in the Philippines.[22][23][24][25][26] Felix Y. Manalo officially registered the church with the Philippine Government on July 27, 1914[27] and because of this, most publications refer to him as the founder of the church. Felix Manalo claimed that he was restoring the church of Christ that was lost for 2,000 years. He died on April 12, 1963, aged 76.

The Iglesia ni Cristo is known for its large evangelical missions. The largest of which was the Grand Evangelical Mission (GEM) which also occurred simultaneously on 19 sites across the country. In Manila site alone, more than 600,000 people attended the event.[28] Other programs includes the Lingap sa Mamamayan (Aid to Humanity),[29] The Kabayan Ko Kapatid Ko (My Countrymen, My Brethren) and various resettlement projects for affected individuals.[30]

Jesus Miracle Crusade International Ministry

The Jesus Miracle Crusade International Ministry (JMCIM) is an apostolic Pentecostal religious group from the Philippines which believes in the gospel of Jesus Christ with signs, wonders, miracles and faith in God for healing. JMCIM was founded by evangelist Wilde E. Almeda on February 14, 1975.

Members Church of God International

Members Church of God International (Filipino: Mga Kaanib sa Iglesia ng Dios Internasyonal) is a religious organization popularly known through its Filipino television program, Ang Dating Daan (English Program "The Old Path", in Spanish "El Camino Antiguo", in Portuguese "O Caminho Antigo")

The church is known for their "Bible Expositions", where guests and members are given a chance to ask any biblical question to the "Overall Servant" Eliseo Soriano. He and his associates refute teachings of asked religions which are, according to Soriano, "not biblical" and discuss controversial passages. Besides general preaching, they also established charity works. Among these humanitarian services are the charity homes for the senior citizens and orphaned children and teenagers; transient homes; medical missions; full college scholarship; start-up capital for livelihood projects; vocational training for the differently-abled; free legal assistance; free bus, jeepney, and train rides for commuters and senior citizens, and; free Bibles for everyone. MCGI is now one of the major blood donor in the Philippines, as acknowledged by the Philippine National Red Cross.[31]

Most Holy Church of God in Christ Jesus

The Most Holy Church of God in Christ Jesus (Filipino: Kabanalbanalang Iglesia ng Dios kay Kristo Hesus),[32][33] is an independent Christian denomination officially registered in the Philippines by Teofilo D. Ora in May 1922. The Church claims to restore the visible Church founded in Jerusalem by Christ Jesus. It has spread to areas including California, USA; Calgary, Canada, Dubai, UAE and other Asian countries. The Church will be celebrating its centennial anniversary in May 2022.

The church was founded by Bishop Teofilo D. Ora in 1922. He, along with Avelino Santiago and Nicolas Perez, split off from the Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ) in 1922. They initially called their church Iglesia Verdadera de Cristo Hesus (True Church of Christ Jesus). However, following a religious doctrine controversy, Nicolas Perez split off from the group and registered an offshoot called Iglesia ng Dios kay Kristo Hesus, Haligi at Suhay ng Katotohanan (Church of God in Christ Jesus, the Pillar and Support of the Truth). Teofilo D. Ora was bishop until his death in 1969. He was officially succeeded by Bishop Salvador C. Payawal who led the church until 1989. Subsequent bishops were Bishop Gamaliel T. Payawal (1989 to 2003) and Bishop Isagani N. Capistrano (2003–present). It was during Gamaliel Payawal's tenure when the church was renamed as Most Holy Church of God in Christ Jesus.

Apostolic Catholic Church

The Apostolic Catholic Church (ACC) is an independent catholic denomination founded in the 1980s in Hermosa, Bataan. It formally separated in the Catholic Church in 1992 when Patriarch Dr. John Florentine Teruel registered it as a Protestant and Independent Catholic denomination. Today, it has more than 5 million members worldwide. The largest international congregations are in Japan, United States and Canada.

Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy has been continuously present in the Philippines for more than 200 years.[34] It is represented by two groups, by the Exarchate of the Philippines (a jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople governed by the Orthodox Metropolitanate of Hong Kong and Southeast Asia), and by the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Mission in the Philippines (a jurisdiction of the Antiochian Orthodox Church governed by the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand, and All Oceania). In 1999, it was asserted that there were about 560 Orthodox church members in the Philippines.[35]

Protestantism

Protestantism arrived in the Philippines with the take-over of the islands by Americans at the turn of the 20th century. In 1898, Spain lost the Philippines to the United States. After a bitter fight for independence against its new occupiers, Filipinos surrendered and were again colonized. The arrival of Protestant American missionaries soon followed. As of 2015, Protestants comprised about 10%–15% of the population, with an annual growth rate of 10% since 1910[36] and constitute the largest Christian grouping after Catholicism. Protestants were 10.8% of the population in 2010.[37] Protestant church organizations established in the Philippines during the 20th century include the following:

- Association of Fundamental Baptist Churches in the Philippines

- Awake International Ministries (Evangelical)

- Baptist Bible Fellowship in the Philippines (Baptist)

- Bread of Life Ministries International (Evangelical)

- Cathedral of Praise (Pentecostal)

- Christ's Commission Fellowship (Evangelical)

- Christ Living Epistle Ministries Inc. (Full Gospel/Pentecostal).

- Christian and Missionary Alliance Churches of the Philippines

- Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee)

- Church of God in Christ (Memphis, Tennessee)

- Church of the Foursquare Gospel in the Philippines (Full Gospel/Pentecostal)

- Church of the Nazarene (Holiness movement)

- Citichurch Cebu (Pentecostal)

- Conservative Baptist Association of the Philippines (Baptist)

- Convention of Philippine Baptist Churches (Baptist)

- Day by Day Christian Ministries (Evangelical)

- Episcopal Church in the Philippines (Anglican)

- Every Nation Churches and Ministries (Pentecostal)

- Grace Christian Church of the Philippines

- Greenhills Christian Fellowship (Conservative Baptist)

- Heartland Covenant Church (formerly Jesus Cares Ministries)

- Iglesia Evangelica Metodista en las Islas Filipinas

- Iglesia Evangelica Unida de Cristo

- Jesus Flock Gateway Church (Full Gospel)

- Jesus Is Lord Church Worldwide (Pentecostal)

- Jesus Miracle Crusade International Ministry (Full Gospel)

- Jesus the Anointed One Church (Pentecostal)

- Lutheran Church in the Philippines (Lutheran)

- Luzon Convention of Southern Baptists (Baptist)

- Mindanao and Visayas Convention of Southern Baptists (Baptist)

- New Life Christian Center (Pentecostal)

- Pentecostal Global Ministries Full Gospel Church (Pentecostal)

- Pentecostal Missionary Church of Christ (4th Watch) (Pentecostal)

- Philippine Evangelical Holiness Churches

- Philippines General Council of the Assemblies of God

- Presbyterian Church of the Philippines

- Redeeming Grace Christian Centre

- Salvation Army

- Seventh-day Adventist Church

- TEAM Ministries international

- The Blessed Word International Church (Evangelical)

- The United Methodist Church (Methodist)

- Union Church Manila

- Union Espiritista Cristiana de Filipinas (established on 1905)[38]

- United Church of Christ in the Philippines (Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Disciples, United Brethren, Methodist).

- United Evangelical Church of the Philippines

- United Methodist Church https://www.umc.org/en/content/philippines-episcopal-areas

- Victory Christian Fellowship (Evangelical)

- Vineyard Christian Fellowship (Evangelical)

- Word for the World Christian Fellowship (Evangelical)

- Word of Life World Mission Church (Pentecostal)

- Words of Life Christian Ministries

- His Life Ministries (Non-Denominational)

- His Life City Church (Pentecostal)

- City of God Celebration Church. by Bishop Virgilio Senados {Pentecostal}

Members Church of God in Jesus Christ Worldwide

Members Church of God in Jesus Christ Worldwide (also known as Miembro de la Iglesia de Dios en Todo el Mundo Inc.) is an independent Christian organization with headquarters in the Philippines led by Wilfredo "Bro. Willy" Santiago, a former Bible reader for Members Church of God International (MCGI). Willy Santiago was excommunicated from MCGI due to various violations. Santiago is currently building a new church headquarters in Malolos, Bulacan.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in the Philippines was founded during the Spanish–American War in 1898. Two men from Utah who were members of the United States artillery battery, and who were also set apart as missionaries by the Church before they left the United States, preached while stationed in the Philippines. Missionary work picked up after World War II, and in 1961 the Church was officially registered in the Philippines.[39] In 1969, the Church had spread to eight major islands and had the highest number of baptisms of any area in the Church. Membership was 805,209 in 2019.[40] A temple was built in 1984 which is located in Manila, and a second temple was completed in Cebu City in 2010. As of 2019, four more LDS temples have been announced, they are planned to be built in Urdaneta, Cagayan de Oro, Davao, as well as a second temple in the greater Manila area.[41]

Other Christians

- The Bible Student movement, from which Jehovah's Witnesses later developed, was introduced to the Philippines in 1912, when the president of the Watch Tower Society, Charles Taze Russell, gave a talk at the former Manila Grand Opera House.[42] In 1993, a Supreme Court case involving the Witnesses resulted in the reversal of an earlier 1959 Supreme Court decision and in upholding "the right of children of Jehovah's Witnesses to refrain from saluting the flag, reciting the pledge of allegiance, and singing the national anthem."[43][44] As of 2015, there were officially 201,001 active members in the Philippines in 3,156 congregations nationwide. Their 2013 observance of the annual Memorial of Christ's death attracted an attendance of 543,282 in the country.[45]

- The Kingdom of Jesus Christ, the Name Above Every Name was founded by Pastor Apollo C. Quiboloy on September 1, 1985. Pastor Quiboloy claims to be the "Appointed" Son of God, that salvation is through him, that he is the residence of the God the Father and that he restores the Kingdom of God in the gentile settings.

- The Seventh-day Adventist Church was founded by Ellen G. White, which is best known for its teaching that Saturday, the seventh day of the week, is the Sabbath, and that the second advent of Christ is imminent. Colloquially called Sabadístas by outsiders, Filipino Adventists numbered 571,653 in 88,706 congregations as of 2007, and with an annual membership growth rate of 5.6%.[46]

- United Pentecostal Church International (Oneness) originated in the United States as an offshoot of the Pentecostal movements in the 1920s. The church is a proponent of the belief of modalism to describe God, and is non-trinitarian in its conception of God.

- Jesus Christ To God be the Glory (Friends Again) was founded by Luis Ruíz Santos in 1988.

- Churches of Christ (Churches of Christ 33 AD/the Stone-Campbellites) is a restorationist movement that distinctly believes in a set of steps or ways to attain salvation, among of which is prerequisite immersion baptism.

- True Jesus Church a "oneness" movement that started in the People's Republic of China.

- Jesus is Our Shield Worldwide Ministries (commonly known as Oras ng Himala, "Hour of Miracle[s]") was founded by Renato D. Carillo, who claims to be the end-times apostle.

- Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UCKG Help Center) was founded by Edir Macedo in 1977 in Brazil.

- Unification Church, founded by Sun Myung Moon in what is today South Korea.

- Jesus is I.L Church, founded by I.L Noval in 2011. The church has exponentially expanded since then and now has about 76,000 members.

Islam

Islam reached the Philippines in the 14th century with the arrival of Muslim traders from the Persian Gulf, Southern India, and their followers from several sultanate governments in Maritime Southeast Asia. Islam's predominance reached all the way to the shores of Manila Bay, home to several Muslim kingdoms. During the Spanish conquest, Islam had a rapid decline as the predominant monotheistic faith in the Philippines as a result of the introduction of Roman Catholicism by Spanish missionaries and via the Spanish Inquisition.[47] The southern Filipino tribes were among the few indigenous Filipino communities that resisted Spanish rule and conversions to Roman Catholicism. The vast majority of Muslims in Philippines follow Sunni Islam of Shafi school of jurisprudence, with small Shiite and Ahmadiyya minorities.[6] Islam is the oldest recorded monotheistic religion in the Philippines.

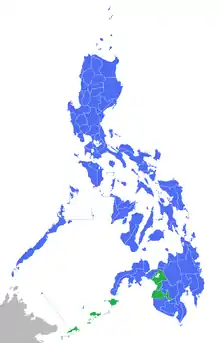

As of 2015. According to the Philippine Statistics Authority,[16] the Muslim population of Philippines in 2015 was 5.57%. However, a 2012 estimate by the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF) stated that there were 10.7 million Muslims, or approximately 11 percent of the total population.[3][48] Some Muslim scholars have observed that difficulties in getting accurate numbers have been compounded in some Muslim areas by the hostility of the inhabitants to government personnel, leading to difficulty in getting accurate data for the Muslim population in the country.[49] The majority of Muslims live in Mindanao and nearby islands.[50][51]

History

In 1380 Karim ul' Makhdum the first Arabian trader reached the Sulu Archipelago and Jolo in the Philippines and through trade throughout the island established Islam in the country. In 1390 the Minangkabau's Prince Rajah Baguinda and his followers preached Islam on the islands.[52] The Sheik Karimal Makdum Mosque was the first mosque established in the Philippines on Simunul in Mindanao in the 14th century. Subsequent settlements by Arab missionaries traveling to Malaysia and Indonesia helped strengthen Islam in the Philippines and each settlement was governed by a Datu, Rajah and a Sultan.

By the next century conquests had reached the Sulu islands in the southern tip of the Philippines where the population was animistic and they took up the task of converting the animistic population to Islam with renewed zeal. By the 15th century, half of Luzon (Northern Philippines) and the islands of Mindanao in the south had become subject to the various Muslim sultanates of Borneo and much of the population in the South were converted to Islam. However, the Visayas was largely dominated by Hindu-Buddhist societies led by rajahs and datus who strongly resisted Islam. One reason could be due to the economic and political disasters prehispanic Muslim pirates from the Mindanao region bring during raids. These frequent attacks gave way to naming present-day Cebu as then-Sugbo or scorched earth which was a defensive technique implemented by the Visayans so the pirates have nothing much to loot.[53][54]

Moro (derived from the Spanish word meaning Moors) is the appellation inherited from the Spaniards, for Filipino Muslims and tribal groups of Mindanao. The Moros seek to establish an independent Islamic province in Mindanao to be named Bangsamoro. The term Bangsamoro is a combination of an Old Malay word meaning nation or state with the Spanish word Moro. A significant Moro rebellion occurred during the Philippine–American War. Conflicts and rebellion have continued in the Philippines from the pre-colonial period up to the present.

Muslim Mindanao

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) comprises the Philippines' predominantly Muslim provinces, namely: Basilan (except Isabela City), Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi, and the Islamic City of Marawi. It is the only region with its own government. The regional capital is at Cotabato City, although this city is outside of its jurisdiction.

Other religions

Judaism

In the 1590s some Jews fleeing from the Inquisition were recorded to have come to the Philippines.[55] In 2006, Metro Manila boasted the largest Jewish community in the Philippines, which consisted of roughly 100 families.[55] As of 2018, the Jewish population comprised between 100 and 300 individuals, depending on one's definition of Jew.[56]

The country's only synagogue, Beth Yaacov, is located in Makati.[55] There are other Jews elsewhere in the country,[55] but these are much fewer and almost all transients,[57] either diplomats or business envoys, and their existence is almost totally unknown in mainstream society. There are a few Israelis in Manila recruiting caregivers for Israel, some work in call centers, businessmen and a few other executives.

Hinduism

The Srivijaya Empire and Majapahit Empire on what is now Malaysia and Indonesia, introduced Hinduism and Buddhism to the islands.[58] Ancient statues of Hindu-Buddhist gods have been found in the Philippines dating as far back as 600 to 1600 years from present.[59]

The archipelagos of Southeast Asia were under the influence of Hindu Tamil people, Gujarati people and Indonesian traders through the ports of Malay-Indonesian islands. Indian religions, possibly an amalgamated version of Hindu-Buddhist arrived in Philippines archipelago in the 1st millennium, through the Indonesian kingdom of Srivijaya followed by Majapahit. Archeological evidence suggesting exchange of ancient spiritual ideas from India to the Philippines includes the 1.79 kilogram, 21 carat gold Hindu goddess Agusan (sometimes referred to as Golden Tara), found in Mindanao in 1917 after a storm and flood exposed its location.

Another gold artifact, from the Tabon caves in the island of Palawan, is an image of Garuda, the bird who is the mount of Vishnu. The discovery of sophisticated Hindu imagery and gold artifacts in Tabon caves has been linked to those found from Oc Eo, in the Mekong Delta in Southern Vietnam.[60] These archaeological evidence suggests an active trade of many specialized goods and gold between India and Philippines and coastal regions of Vietnam and China. Golden jewelry found so far include rings, some surmounted by images of Nandi – the sacred bull, linked chains, inscribed gold sheets, gold plaques decorated with repoussé images of Hindu deities.[61]

Today Hinduism is largely confined to the Indian Filipinos and the expatriate Indian community. There are temples also for Sikhism, also located in the provinces and in the cities, sometimes located near Hindu temples. The two Paco temples are well known, comprising a Hindu temple and a Sikh temple.

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith in the Philippines started in 1921 with the first Baháʼí first visiting the Philippines that year,[62] and by 1944 a Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was established.[63] In the early 1960s, during a period of accelerated growth, the community grew from 200 in 1960 to 1000 by 1962 and 2000 by 1963. In 1964 the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the Philippines was elected and by 1980 there were 64,000 Baháʼís and 45 local assemblies.[64] The Baháʼís have been active in multi/inter-faith developments. The 2010 World Christian Encyclopedia estimates the Philippines has the world's sixth largest population of Baháʼís, at just over 275,000.[65]

Buddhism

No written record exists about the early Buddhism in the Philippines. However, archaeological discoveries and the few scant references in the other nations' historical records can tell about the existence of Buddhism from the 9th century onward in the islands. These records mention the independent states that comprise the Philippines and which show that they were not united as one country in the early days. Archaeological finds include Buddhist artifacts. The style are of Vajrayana influence.

Loanwords with Buddhist context appear in languages of the Philippines.[66][67] Archaeological finds include Buddhist artifacts.[68][69] The style are of Vajrayana influence.[70][71] The Philippines's early states must have become the tributary states of the powerful Buddhist Srivijaya empire that controlled the trade and its sea routes from the 6th century to the 13th century in Southeast Asia. The states's trade contacts with the empire long before or in the 9th century must have served as the conduit for introducing Vajrayana Buddhism to the islands.

Both Srivijaya empire in Sumatra and Majapahit empire in Java were unknown in history until 1918 when the Ecole Francaise d'Extreme Orient's George Coedes postulated their existence because they had been mentioned in the records of the Chinese Tang and Sung imperial dynasties. Ji Ying, a Chinese monk and scholar, stayed in Sumatra from 687 to 689 on his way to India. He wrote on the Srivijaya's splendour, "Buddhism was flourishing throughout the islands of Southeast Asia. Many of the kings and the chieftains in the islands in the southern seas admire and believe in Buddhism, and their hearts are set on accumulating good action."

Both empires replaced their early Theravada Buddhist religion with Vajrayana Buddhism in the 7th century.[72]

In 2010 Buddhism was practiced by around 0.05% of the population,[16] concentrated among Filipinos of Chinese descent[73] and there are several prominent Buddhist temples in the country like Seng Guan Temple in Manila and Lon Wa Buddhist Temple in Mindanao.

Indigenous religions

Indigenous Philippine folk religions, also referred to as Anitism,[75][76] are a body of myths, tales, and superstitions held by Filipinos (composed of more than a hundred ethnic peoples in the Philippines), mostly originating from beliefs held during the pre-Hispanic era. Some of these beliefs stem from pre-Christian religions that were specially influenced by Hinduism and were regarded by the Spanish as "myths" and "superstitions" in an effort to de-legitimize legitimate precolonial beliefs by forcefully replacing those native beliefs with colonial Christian myths and superstitions. Today, some of these precolonial beliefs are still held by many Filipinos, both in urban and rural areas.

Philippine mythology is incorporated from various sources, having similarities with Indonesian and Malay myths, as well as Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, and Christian traditions, such as the notion of heaven (kaluwalhatian, kalangitan, kamurawayan, etc.), hell (kasamaan, sulad, etc.), and the human soul (kaluluwa, kaulolan, etc.). Philippine mythology attempts to explain the nature of the world through the lives and actions of deities (gods, goddesses), heroes, and mythological creatures. The majority of these myths were passed on through oral tradition, and preserved through the aid of community spiritual leaders or shamans (babaylan, katalonan, mumbaki, baglan, machanitu, walian, mangubat, bahasa, etc.) and community elders.

Today, many ethnic peoples continue to practice and conserve their unique indigenous religions, notably in ancestral domains, although foreign and foreign-inspired Hispanic and Arabic religions continue to interfere with their life-ways through conversions, land-grabbing, inter-marriage, and/or land-buying. Various scholarly works have been made regarding Anitism and its many topics, although much of its stories and traditions are still undocumented by the international anthropological and folkloristic community.[77][78][75][79]

Presently, around 2% of the population are Anitists, concentrating in the Cordillera Administrative Region, Palawan, Mindoro, Western Visayas, and Mindanao. Specific communities throughout the Philippines also adhere to Anitism, while more than 90% of the Philippine national population continue to believe in certain Anitist belief system, despite adhering to another religion.[80][74] The 2020 census recorded around 0.1% of the population as practicing Philippine traditional religions.[16]

Revitalization attempts

In search of a national culture and identity, away from those imposed by Spain during the colonial age, Filipino revolutionaries during the Philippine revolution proposed to revive the indigenous Philippine folk religions and make them the national religion of the entire country. The Katipunan opposed the religious teachings of the Spanish friars, saying that they "obscured rather than explained religious truths." After the revival of the Katipunan during the Spanish–American War, an idealized form of the folk religions was proposed by some, with the worship of God under the ancient name of Bathala, which applies to all supreme deities under the many ethnic pantheons in the Philippines.[81]

No religion

Dentsu Communication Institute Inc., Research Centre for Japan said in 2006 that about 11% of the population is irreligious.[82] Other sources put the number at less than 0.1%.[83]

The Philippine Atheists and Agnostics Society (PATAS) is a nonprofit organization for the public understanding of atheism and agnosticism in the Philippines which educates society, and eliminates myths and misconceptions about atheism and agnosticism.[84] In February 2009, Filipino Freethinkers[85] was formed. Since 2011, the Philippine Atheists and Agnostics Society has held its OUT Campaigns in Rizal Park and Quezon Memorial Circle. Also it held two feeding programs "Good without Religion" in Bacoor, Cavite.[86] The society also is a member affiliate and associate of various international atheist organizations such as the Atheist Alliance International, Institute for Science and Human Values, and the International Humanist and Ethical Union, as one among secular organizations that promotes free thought and scientific development in the Philippines.[87] The 2010 Philippine Census reported the religion of about 0.08% of the population as "none".[16]

Religion and politics

The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines declares: The separation of Church and State shall be inviolable. (Article II, Section 6), and, No law shall be made respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. The free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed. No religious test shall be required for the exercise of civil or political rights. (Article III, Section 5). Joaquin Bernas, a Filipino Jesuit specializing in constitutional law, acknowledges that there were complex issues that were brought to court and numerous attempts to use the separation of Church and State against the Catholic Church, but he defends the statement, saying that "the fact that he [Marcos] tried to do it does not deny the validity of the separation of church and state".[88]

On April 28, 2004, the Philippines Supreme Court reversed the ruling of a lower court ordering five religious leaders to refrain from endorsing a candidate for elective office.[89][90] Manila Judge Conception Alarcon-Vergara had ruled that the "head of a religious organization who influences or threatens to punish members could be held liable for coercion and violation of citizen's right to vote freely". The lawsuit filed by Social Justice Society party stated that "the Church's active participation in partisan politics, using the awesome voting strength of its faithful flock, will enable it to elect men to public office who will in turn be forever beholden to its leaders, enabling them to control the government".

They claimed that this violates the Philippine constitution's separation of Church and State clause. The named respondents were the Archbishop of Manila Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, El Shaddai Movement Leader Mike Velarde, Iglesia ni Cristo Executive Minister Eduardo V. Manalo and Jesus Is Lord Church Worldwide leader Eddie Villanueva. Manalo's Iglesia ni Cristo practices bloc voting. Former Catholic Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin had been instrumental in rallying support for the assumption to power of Corazon Aquino and Gloria Arroyo. Velarde supported Fidel V. Ramos, Joseph Estrada, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and Benigno Aquino III while Villanueva endorsed Fidel Ramos and Jose De Venecia. The papal nuncio agreed with the decision of the lower court[91] while the other respondents challenged the decision.[92][93]

See also

References

- "East Asia/Southeast Asia :: Philippines — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- Philippines in Figures : 2014 Archived July 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Philippine Statistics Authority.

- Philippines. 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom (Report). United States Department of State. July 28, 2014. SECTION I. RELIGIOUS DEMOGRAPHY. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

The 2000 survey states that Islam is the largest minority religion, constituting approximately 5 percent of the population. A 2012 estimate by the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF), however, states that there are 10.7 million Muslims, which is approximately 11 percent of the total population.

- RP closer to becoming observer-state in Organization of Islamic Conference Archived June 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. (May 29, 2009). The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2009-07-10, "Eight million Muslim Filipinos, representing 10 percent of the total Philippine population, ...".

- McAmis, Robert Day (2002). Malay Muslims: The History and Challenge of Resurgent Islam in Southeast Asia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 18–24, 53–61. ISBN 0-8028-4945-8. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- R Michael Feener; Terenjit Sevea (2009). Islamic Connections: Muslim Societies in South and Southeast Asia. p. 144. ISBN 9789812309235. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project: Philippines Archived July 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Pew Research Center. 2010.

- "Buddhism in Philippines, Guide to Philippines Buddhism, Introduction to Philippines Buddhism, Philippines Buddhism Travel". Archived from the original on August 20, 2007.

- "Philippines – Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project". Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Punjabi Community Involved in Money Lending in Philippines Braces for 'Crackdown' by New President". May 18, 2016.

- "2011 Gurdwara Philippines: Sikh Population of the Philippines". Archived from the original on December 1, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- Note: The Irreligious population is taken from the Catholic majority. The 65% is from the Filipino American population which have a more accurate demographic count sans the Muslim population of the Philippines.

- Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths Archived May 3, 2014, at WebCite, Pew Research. July 19, 2012.

- 5 facts about Catholicism in the Philippines Archived December 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Pew Research. January 9, 2015.

- On being godless and good: Irreligious Pinoys speak out:'God is not necessary to be a good' Archived September 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Rappler. June 4, 2015.

- Table: Christian Population in Numbers by Country Archived December 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Pew Research. December 19, 2011.

- "Philippine Church National Summary". philchal.org. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- "500 years of Protestantism(World Christian Database)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 19, 2017.

- "Table 1.10; Household Population by Religious Affiliation and by Sex; 2010" (PDF). 2015 Philippine Statistical Yearbook. East Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority: 1–30. October 2015. ISSN 0118-1564. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Philippines in Figures; 2018" (PDF). Philippines in Figures. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority: 23. June 2018. ISSN 1655-2539. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- "MAP: Catholicism in the Philippines". Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Russel, Susan. "Christianity in the Philippines". Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- News, Dharel Placido, ABS-CBN. "Duterte signs law declaring Dec. 8 a nationwide holiday". Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "Iglesia ni Kristo". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- Sanders, Albert J., "An Appraisal of the Iglesia ni Cristo," in Studies in Philippine Church History, ed. Anderson, Gerald H. (Cornell University Press, 1969)

- Bevans, Stephen B.; Schroeder, Roger G. (2004). Constants in Context: A Theology of Mission for Today (American Society of Missiology Series). Orbis Books. p. 269. ISBN 1-57075-517-5.

- Carnes, Tony; Yang, Fenggang (2004). Asian American religions: the making and remaking of borders and boundaries. New York: New York University Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-8147-1630-4.

- Kwiatkowski, Lynn M. (October 1999). Struggling With Development: The Politics Of Hunger And Gender In The Philippines. Westview Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-8133-3784-5.

- Palafox, Quennie Ann J. 'First Executive Minister of the Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ)' Archived February 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine "National Historical Institute"

- "I.N.C. holds 19 simultaneous grand evangelical missions nationwide". April 2, 2012. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Lingap Sa Mamamayan | Iglesia Ni Cristo Media". incmedia.org. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Fact sheet: INC resettlement and eco-farming site". Eagle News. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Philippine Red Cross". Archived from the original on December 21, 2012.

- "Religions in the Philippines". pinoysites.org. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- "Religions in the Philippines". philippine-directory.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2007.

- "Orthodox Christians in Philippines". Orthodox Church in the Philippines. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- Article Provided By Rev. Philemon Castro. "The Orthodox Church In The Philippines". Dimitris Papadias, Professor at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Hong Kong. Archived from the original on October 7, 1999.

- "500 years of Protestantism" (PDF). 500 years of Protestantism. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 8, 2019.

- "Table: Christian Population as Percentages of Total Population by Country". Pew Research. December 19, 2011.

- "Union Espiritista Cristiana de Filipinas, Inc". Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- "News of the Church: New Temple Announcement Answers Members' Prayers". Liahona. September 2006. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- "Facts and Statistics – Philippines". Newsroom – The Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- "Temples in the Philippines". ph.churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 2003 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses, p.154

- Awake! January 8, 1994, p.22

- G.R. No. 95770 March 1, 1993 Archived January 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Chanrobles.com. Retrieved on March 27, 2012.

- "2014 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses". Watch Tower Society. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- Philippines Archived July 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Adventist Atlas Archived June 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- Laforteza, Elaine Marie Carbonell (2016). The Somatechnics of Whiteness and Race: Colonialism and Mestiza Privilege. Routledge. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1-317-01516-1.

- "Philippines". Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- O'Shaughnessy, Thomas J (1975). "How Many Muslims Has the Philippines?". Philippine Studies. 23 (3): 375–382. JSTOR 42632278.

- "International Religious Freedom Report for 2014". United States Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- RP closer to becoming observer-state in Organization of Islamic Conference Archived June 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. (May 29, 2009).The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2009-07-10, "Eight million Muslim Filipinos, representing 10 percent of the total Philippine population, ...".

- "Kerinduan orang-orang moro". TEMPO- Majalah Berita Mingguan. June 23, 1990. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012.

- "A Rapid Journal Article Volume 10, No. 2". Celestino C. Macachor. Archived from the original on July 3, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- "The Aginid". Maria Eleanor Elape Valeros. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- Philippines Jewish Community Archived December 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Times Asia (May 2006), pp.12–13. Retrieved on July 16, 2019.

- Della Pergola, Sergio (2018). "World Jewish Population, 2018" (PDF). Berman Jewish DataBank. American Jewish Year Book 2018. p. 53. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Schlossberger, E. Cauliflower and Ketchup Archived July 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- "History of Buddhism". Buddhism in the Philippines. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- Thakur, Upendra (1986). Some Aspects of Asia and Culture. Abhinav Publications.

- Anna T. N. Bennett (2009), "Gold in early Southeast Asia" Archived May 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, ArcheoSciences, Volume 33, pp 99–107

- Dang V.T. and Vu, Q.H., 1977. "The excavation at Giong Ca Vo site." Journal of Southeast Asian Archaeology 17: 30–37

- Hassall, Graham; Austria, Orwin (January 2000). "Mirza Hossein R. Touty: First Baháʼí known to have lived in the Philippines". Essays in Biography. Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-020-9. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. The Baháʼí World. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. Table of Contents and pp.513, 652–9. ISBN 0-85398-234-1. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- "QuickLists: Most Baha'i Nations (2010)". Association of Religion Data Archives. 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- Virgilio S. Almario, UP Diksunaryong Filipino

- Khatnani, Sunita (October 11, 2009). "The Indian in the Filipino". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- Jesus Peralta, "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments CB Philippines," Arts of Asia, 1981, 4:54–60

- Art Exhibit: Philippines' 'Gold of Ancestors' Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine in Newsweek.

- Laszlo Legeza, "Tantric Elements in Pre-Hispanic Gold Art," Arts of Asia, 1988, 4:129–133.

- Camperspoint: History of Palawan Archived January 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed August 27, 2008.

- filipinobuddhism (November 8, 2014). "Early Buddhism in the Philippines". Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Yu, Jose Vidamor B. (2000). Inculturation of Filipino-Chinese Culture Mentality. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-88-7652-848-4. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "The Moon God Libulan/ Bulan : Patron deity of homosexuals?".

- "ANITISM AND PERICHORESIS: TOWARDS A FILIPINO CHRISTIAN ECO-THEOLOGY OF NATURE". elibrary.ru. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Almocera, Reuel (May 28, 1990). "Christianity encounters Filipino spirited-world beliefs: a case study" – via dspace.aiias.edu.

- Hislop, Stephen K. "ANITISM: A SURVEY OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS NATIVE TO THE PHILIPPINES" (PDF). Asian Studies: 144–156.

- "Download Karl Gaverza's Incredible Philippine Mythology Thesis".

- Almocera, Reuel (May 1, 1990). "Christianity encounters Filipino spirited-world beliefs: a case study" – via dspace.aiias.edu.

- "LAKAPATI: The "Transgender" Tagalog Deity? Not so fast…".

- L. W. V. Kennon (August 1901). "The Katipunan of the Philippines". The North American Review. University of Northern Iowa. 17 (537): 211, 214. JSTOR 25105201.

- "図録▽世界各国の宗教". www2.ttcn.ne.jp. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015.

- French, Michael (March 5, 2017). "The New Atheists of the Philippines". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "Agnosticism and Atheism in the Philippines". The Free Thinker. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- "Filipino Freethinkers Official Website". Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- Catholic Philippines gains its first atheist society Archived July 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Freethinker.co.uk. Retrieved on March 27, 2012.

- Kevin Enriquez (December 17, 2015). "Humanism in the Philippines". Young Humanists International.

- Joaquin G. Bernas (1995). The Intent of the 1986 Constitution Writers. Published & distributed by Rex Book Store. p. 86. ISBN 9789712319341.

- Philippine Daily Inquirer. News.google.com (May 1, 2004). Retrieved on 2012-03-27.

- Velarde vs Social Justice Society : 159357 : April 28, 2004 : J. Panganiban : En Banc : Decision Archived April 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Sc.judiciary.gov.ph. Retrieved on March 27, 2012.

- No role for Church in politics. Manila Standard. June 22, 2003

- Philip C. Tubeza Iglesia appeals court ruling infringing on group's belief. Philippine Daily Inquirer. July 20, 2003

- SC ruling sought on sect's vote. Philippine Daily Inquirer. April 1, 2004