Remedies in Singapore constitutional law

The remedies available in a Singapore constitutional claim are the prerogative orders – quashing, prohibiting and mandatory orders, and the order for review of detention – and the declaration. As the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1985 Rev. Ed., 1999 Reprint) is the supreme law of Singapore, the High Court can hold any law enacted by Parliament, subsidiary legislation issued by a minister, or rules derived from the common law, as well as acts and decisions of public authorities, that are inconsistent with the Constitution to be void. Mandatory orders have the effect of directing authorities to take certain actions, prohibiting orders forbid them from acting, and quashing orders invalidate their acts or decisions. An order for review of detention is sought to direct a party responsible for detaining a person to produce the detainee before the High Court so that the legality of the detention can be established.

The High Court also has the power to grant declarations to strike down unconstitutional legislation. Article 4 of the Constitution states that legislation enacted after the commencement of the Constitution on 9 August 1965 that is inconsistent with the Constitution is void, but the Court of Appeal has held that on a purposive reading of Article 4 even inconsistent legislation enacted before the Constitution's commencement can be invalidated. In addition, Article 162 places a duty on the Court to construe legislation enacted prior to the commencement of the Constitution into conformity with the Constitution.

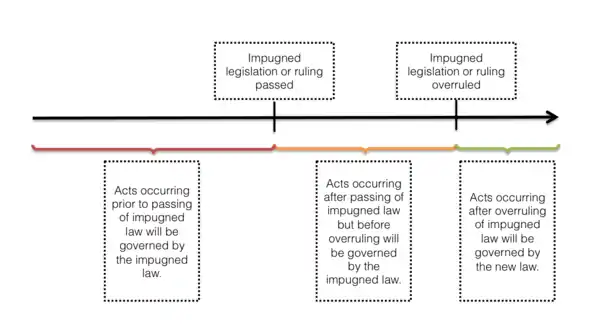

There are two other more unusual remedies that may be granted. When a law is declared unconstitutional, the Court of Appeal may apply the doctrine of prospective overruling to prevent prejudice to an accused by overruling the law only from the date of the judgment but preserving it with regards to acts done prior to the judgment. In Canada, the Supreme Court has held that unconstitutional laws can be given temporary validity to prevent a legal vacuum caused by the voiding of laws until the legislature has had time to re-enact the laws in a constitutional manner. This remedy has yet to be applied in Singapore.

Damages and injunctions are not remedies that are available in constitutional claims in Singapore.

Supremacy of the Constitution

The Constitution of the Republic of Singapore[1] is the supreme law of the land. This is supported by Article 4 of the Constitution, which provides:

This Constitution is the supreme law of the Republic of Singapore and any law enacted by the Legislature after the commencement of this Constitution which is inconsistent with this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.

The court has the power and duty to uphold the provisions in the Constitution.[2] As the Constitution is supreme, the judiciary can hold any law laid down by Parliament, subsidiary legislation issued by a minister, or rules derived from common law as unconstitutional, and therefore void. The constitutionality of decisions and orders of public authorities can be challenged as well, as the Court of Appeal held in Eng Foong Ho v. Attorney-General (2009).[3]

Power of the judiciary to grant remedies

Powers of the High Court

In Singapore, the High Court has the power to issue prerogative orders. These include mandatory orders which have the effect of directing public authorities to take certain actions, prohibiting orders that forbid them from acting, and quashing orders that invalidate their acts or decisions.[4] The High Court also has the power to grant declarations to strike down unconstitutional legislation.[5]

Powers of the Subordinate Courts

The Subordinate Courts have no "jurisdiction relating to the judicial review of any act done or decision made by any person or authority",[6] and do not have the power to grant prerogative orders.[7] Like the High Court, the Subordinate Courts may grant declarations of rights.[8] However, as Magistrate's Courts have no jurisdiction to hear matters that do not involve monetary claims, they cannot declare legislation unconstitutional.[9] On the other hand, it appears that District Courts may be able to do so as no such limitation applies to them, and declaring legislation to be void does not seem to come within the words "judicial review of any act done or decision made by any person or authority".[6]

Previously, under section 56A of the Subordinate Courts Act ("SCA"),[6] when a constitutional question arose in proceedings before the Subordinate Courts, the Courts could refer the question to the High Court and, meanwhile, stay the proceedings. However, this did not mean that the Subordinate Courts could not decide constitutional questions at all. In Johari bin Kanadi v. Public Prosecutor (2008),[10] the High Court held that the Subordinate Courts may decide such questions where the relevant constitutional principles have already been set out by superior courts. Where the principles have not been decided, the question should be referred to the High Court.[11]

Current position in relation to criminal matters

Section 56A of the SCA was repealed by the Criminal Procedure Code 2010 ("CPC")[12] with effect from 2 January 2011.[13] For criminal cases, sections 395(1) and 395(2)(a) of the CPC have the same effect as the repealed section 56A. Questions of law concerning the Constitution can be referred by a Subordinate Court to the High Court for its decision at any stage of proceedings.[14] In Chee Soon Juan v. Public Prosecutor (2011),[15] which concerned a criminal matter, the High Court held that since the Subordinate Courts lack the power to grant prerogative orders, they do not have jurisdiction to deal with the substantive issues of a constitutional challenge. Such questions should be referred to the High Court unless they are "frivolous, or ... made for collateral purposes or to delay proceedings, or if they otherwise constitute an abuse of process". The Court also cautioned against section 395 being used to circumvent the requirement that leave of court must be obtained to apply for prerogative orders (see below).[16]

It is also possible for a Subordinate Court to state a question of law directly to the Court of Appeal, thus bypassing the High Court. This particular procedure is not restricted to constitutional questions of law.[17]

Current position in relation to civil matters

For civil matters, the repeal of section 56A means that the Subordinate Courts Act no longer stipulates that constitutional questions must be referred to the High Court. However, this continues to be necessary in Magistrate's Court proceedings because these courts lack jurisdiction to deal with constitutional questions, as mentioned above. Assuming that declarations can be sought from District Courts, decisions that have been made by these courts may be appealed to the High Court and the Court of Appeal in the usual manner.[18] Alternatively, a party apply to the High Court for the constitutional question to be heard in a separate action.

Challenging a public authority's act or decision as unconstitutional

An applicant who alleges that a public authority's act or decision has infringed his or her constitutional rights may bring a judicial review case to the High Court challenging it. It is likely that the remedies sought will be one or more prerogative orders, though the applicant may also ask for a declaration. (Declarations are discussed below.) All remedies are granted at the Court's discretion.

Quashing orders

The quashing order (formerly known as certiorari) is the most common remedy sought. A quashing order issued by the High Court invalidates a public authority's unconstitutional act or decision. A mandatory order may be linked to the quashing order so as to ensure compliance with the latter.[19] In Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. Ministry of Information and the Arts (1996),[20] the appellants sought leave to apply for a quashing order to invalidate an order banning publications of the International Bible Students Association, a Jehovah's Witnesses organization, on the ground that it violated their right to freedom of religion protected by Article 15(1) of the Constitution. Leave was denied as the court held that the appellants had failed to establish a prima facie case of reasonable suspicion that the Minister had acted unlawfully or breached the Constitution.[21]

Prohibiting orders

A prohibiting order (formerly known as a prohibition) prevents an unconstitutional act from being carried out by a public body. Hence, a key difference between a quashing order and a prohibiting order is that the former operates retrospectively while the latter operates prospectively. Where applicants are aware that unconstitutionality can potentially arise, a prohibiting order can be sought to stop the public body from acting unconstitutionally. Such an order will also prevent the same decisions from occurring in the future.[22] In Singapore, there has yet to be any reported case in which an applicant sought a prohibiting order in a constitutional matter. However, in the administrative law context, in Re Fong Thin Choo (1991)[23] the High Court stated that the legal principles which apply to quashing orders are equally applicable to prohibiting orders.[24]

Mandatory orders

Upon finding that a decision or order of a public authority is unconstitutional, the High Court may grant a mandatory order (formerly known as mandamus) to compel the authority to perform its duties in a manner that is consistent with the Constitution. Although there has yet to be any constitutional case where a mandatory order has been granted, it is likely that the Singapore courts will adopt the same legal principles that apply in administrative law. In the latter, the Court has held that it cannot use a mandatory order to direct how and in what manner a public body should perform its duty.[25] Hence, the Court cannot direct the public body to adopt a particular decision but can only order the body to re-consider its prior decision without lapsing into the unlawfulness that affected it. This is based on the well-settled principle that a reviewing court is limited to determining the legality, and must not deal with the substantive merits, of a decision.[26]

Orders for review of detention

The unlawful detention of a person is a breach of his or her right to personal liberty guaranteed by Article 9(1) of the Constitution. An order for review of detention (formerly known as habeas corpus) can be sought to direct the party responsible for detaining the person to produce the detainee before the High Court so that the legality of the detention can be established. In Re Onkar Shrian (1969),[27] the High Court held:[28]

[T]he writ [of habeas corpus] is a prerogative process of securing the liberty of the subject by affording an effective means of immediate release from unlawful or unjustifiable detention, whether in prison or in private custody. By it the High Court and the judges of that court, at the instance of a subject aggrieved, command the production of that subject, and inquire into the cause of his imprisonment. If there is no legal justification for the detention, the party is ordered to be released.[29]

The power of the Court to require that this be done is specifically mentioned in Article 9(2) of the Constitution, which states: "Where a complaint is made to the High Court or any Judge thereof that a person is being unlawfully detained, the Court shall inquire into the complaint and, unless satisfied that the detention is lawful, shall order him to be produced before the Court and release him."[30]

In Chng Suan Tze v. Minister for Home Affairs (1988),[31] the appellants had been detained without trial under section 8(1) of the Internal Security Act ("ISA")[32] for alleged involvement in a Marxist conspiracy to subvert and destabilize the country. The detention orders were subsequently suspended under section 10 of the Act, but the suspensions were revoked following the release of a press statement by the appellants in which they denied being Marxist conspirators. Having applied unsuccessfully to the High Court for writs of habeas corpus to be issued, the appellants appealed against the ruling. The Court of Appeal allowed the appeal on the narrow ground that the Government had not adduced sufficient evidence to discharge its burden of proving the President was satisfied that the appellants' detention was necessary to prevent them from endangering, among other things, Singapore's security or public order, which was required by section 8(1) of the ISA before the Minister for Home Affairs could make detention orders against them.[33] However, in a lengthy obiter discussion, the Court held that an objective rather than a subjective test should apply to the exercise of discretion by the authorities under sections 8 and 10 of the ISA. In other words, the exercise of discretion could be reviewed by the court, and the executive had to satisfy the court that there were objective facts justifying its decision.[34]

In the course of its judgment, the Court of Appeal noted that at common law if the return to a writ of habeas corpus – the response to the writ that a person holding a detainee had to give[35] – was valid on its face, the court could not inquire further into the matter. However, section 3 of the UK Habeas Corpus Act 1816[36] broadened the court's power by entitling it to examine the correctness of the facts mentioned in the return.[37] The section stated, in part:

Judges to inquire into the Truth of Facts contained in Return. Judge to bail on Recognizance to appear in Term, &c. In all cases provided for by this Act, although the return to any writ of habeas corpus shall be good and sufficient in law, it shall be lawful for the justice or baron, before whom such writ may be returnable, to proceed to examine into the truth of the facts set forth in such return by affidavit ...; and to do therein as to justice shall appertain ...[38]

%252C_Rules_of_Court%252C_Singapore.jpg.webp)

Section 3 of the Act thus "contemplates the possibility of an investigation by the court so that it may satisfy itself where the truth lies".[37] The extent of the investigation depends on whether a public authority's exercise of the power to detain rests on the existence or absence of certain jurisdictional or precedent facts. If so, the court must assess if the authority has correctly established the existence or otherwise of these facts. However, if the power to detain is not contingent on precedent facts, the court's task is only to determine whether there exists evidence upon which the authority could reasonably have acted.[37]

The UK Habeas Corpus Act 1816 applied to Singapore by virtue of the Second Charter of Justice 1826, which is generally accepted to have made all English statutes and principles of English common law and equity in force as at 27 November 1826 applicable in the Straits Settlements (including Singapore), unless they were unsuitable to local conditions and could not be modified to avoid causing injustice or oppression.[39] In 1994, after Chng Suan Sze was decided, the Application of English Law Act[40] was enacted with the effect that only English statutes specified in the First Schedule of the Act continued to apply in Singapore after 12 November 1993.[41] The Habeas Corpus Act 1816 is not one of these statutes, and so appears to have ceased to be part of Singapore law. Nonetheless, it may be argued that High Court should continue to apply a rule equivalent to section 3 of the Act to orders for review of detention because of Article 9(2) of the Constitution, which should not be regarded as having been abridged unless the legislature has used clear and unequivocal language.[42] In addition, in Eshugbayi Eleko v. Government of Nigeria (1931),[43] Lord Atkin said:[44]

In accordance with British jurisprudence no member of the executive can interfere with the liberty or property of a British subject except on the condition that he can support the legality of his action before a court of justice. And it is the tradition of British justice that judges should not shrink from deciding such issues in the face of the executive.

Since an order for review of detention is a remedy for establishing the legality of detention, it may not be used to challenge the conditions under which a person is held, if the detention itself is lawful.[45] Moreover, an order can only be sought where a person is being physically detained, and not if he or she is merely under some other form of restriction such as being out on bail.[46]

Both nationals and non-nationals of a jurisdiction may apply for orders for review of detention. In the UK context, Lord Scarman disagreed with the suggestion that habeas corpus protection only extends to British nationals, stating in Khera v. Secretary of State for the Home Department; Khawaja v. Secretary of State for the Home Department ("Khawaja", 1983),[37] that "[e]very person within the jurisdiction enjoys the equal protection of our laws. There is no distinction between British nationals and others. He who is subject to English law is entitled to its protection."[47]

Quashing, prohibiting and mandatory orders

The procedure for bringing applications for prerogative orders is set out in Order 53 of the Rules of Court ("O. 53").[5] It is a two-stage process. At the first stage, the applicant must request the High Court for leave to apply for one or more prerogative orders. An application for such leave must be made by ex parte originating summons and must be supported by a statement setting out the name and description of the applicant, the relief sought and the grounds on which it is sought; and by an affidavit verifying the facts relied on.[48]

The test for whether leave should be granted is expressed in Public Service Commission v. Lai Swee Lin Linda (2001).[49] The court is "not to embark upon any detailed and microscopic analysis of the material placed before it but ... to peruse the material before it quickly and appraise whether such material disclose[s] an arguable and a prima facie case of reasonable suspicion" that a public authority acted unlawfully.[50]

Leave for a quashing order must generally be applied for within three months of the act or decision that is sought to be quashed. However, an application for leave can still be allowed if the applicant can account for the delay to the satisfaction of the court.[51] There is no specified time limit within which leave to apply for a mandatory order or prohibiting order must be sought. However, the High Court has held that such an application should be made without undue delay.[52]

Should leave be granted, the applicant can proceed to the second stage which is the actual application for one or more of the prerogative orders.[53]

Before O. 53 was amended in 2011, the High Court did not have jurisdiction to grant a declaration under O. 53 proceedings, as a declaration is not a prerogative order. If an applicant wished to obtain both prerogative orders and declarations, a separate action had to be commenced for the declarations.[54] After the amendment, it is now possible to include a claim for a declaration if leave has been granted to the applicant to apply for prerogative orders.[55]

Orders for review of detention

The procedure for applying for an order for review of detention differs from that for obtaining a mandatory order, prohibiting order or quashing order because the latter orders are only available by leave of court, whereas an order for review of detention is issued as of right.[47] The procedure for doing so is set out in Order 54 of the Rules of Court. An application must be made to the High Court[56] by way of an ex parte originating summons, supported, if possible, by an affidavit from the person being restrained which shows that the application is being made at his or her instance and explaining the nature of the restraint. If the person under restraint is unable to personally make an affidavit, someone may do so on his or her behalf, explaining the reason for the inability.[57]

Upon the filing of the application, the Court may either make an order immediately, or direct that a summons for the order for review of detention be issued to enable all the parties involved to present arguments to the Court.[58] If the latter course is taken, the ex parte originating summons, supporting affidavit, order of court and summons must be served on the person against whom the order is sought.[59] Unless the Court directs otherwise, it is not necessary for the person under restraint to be brought before the Court for the hearing of the application. In addition, the Court may order that the person be released while the application is being heard.[60] Once the Court decides to make an order for review of detention, it will direct when the person under restraint is to be brought before the court.[61]

The applicant has the initial burden of showing that he or she has a prima facie case that should be considered by the Court. Once this has been done, it is for the executive to justify the legality of the detention.[62] One commentator has said that the applicant's task is to discharge his or her evidential burden, following which the public authority detaining the applicant has a legal burden of showing that the detention is lawful.[63] The standard of proof required to be achieved by the authority is the civil standard of a balance of probabilities, but "flexibly applied" in the sense that the degree of probability must be appropriate to what is at stake.[64] Thus, in Khawaja Lord Bridge of Harwich said that given the seriousness of the allegations against a detainee and the consequences of the detention, "the court should not be satisfied with anything less than probability of a high degree".[65]

Challenging unconstitutional legislation

As mentioned above, an aggrieved party who alleges that legislation enacted by Parliament violates his or her constitutional rights may apply for a declaration from the High Court that the legislation is unconstitutional.

Article 4

Article 4 of the Constitution affirms that it is the supreme law of Singapore and that "any law enacted by the Legislature after the commencement of this Constitution which is inconsistent with this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void". The date of the Constitution's commencement is defined as 9 August 1965, the date of Singapore's independence.[66]

Article 4 implies that the High Court may void a piece of legislation to the extent of its inconsistency with the Constitution. At present, it is unclear how the Court will apply this requirement. If, say, an entire piece of criminal legislation or one of its provisions is found to be void, a person alleged to have committed an offence created by the impugned legislation may be able to escape liability. To circumvent this, a test of severability, also known as the "blue pencil" test, has been established in the UK. If the unconstitutional parts of the legislation are severable from the constitutional parts, the latter are preserved and remain valid and enforceable. In Director of Public Prosecutions v. Hutchinson (1988),[67] the House of Lords held that two forms of severability must be established for a law to be held partially valid – textual severability and substantial severability. A provision is textually severable if it remains grammatical and correct after severance. It is substantially severable if its substance after severance remains true to its "legislative purpose, operation and effect".[68] However, the court also recognized that a rigid adherence to the test of textual severability may result in unreasonable consequences. It may defeat legislation with a substantial purpose clearly within the lawmaker's power but, by oversight, which was written in a way that exceeded that scope of power. Hence, the "blue pencil" test may still apply to rescue a provision that is not textually severable as long as it does not alter the substantial purpose and effect of the impugned provision.[69]

Article 162

Article 162 of the Constitution provides as follows:

Subject to this Article, all existing laws shall continue in force on and after the commencement of this Constitution and all laws which have not been brought into force by the date of the commencement of this Constitution may, subject as aforesaid, be brought into force on or after its commencement, but all such laws shall, subject to this Article, be construed as from the commencement of this Constitution with such modifications, adaptations, qualifications and exceptions as may be necessary to bring them into conformity with this Constitution. [Emphasis added.]

In Ghaidan v. Godin-Mendoza (2004),[70] the House of Lords recognized that when a former colonial territory of the UK has a written constitution that empowers its courts to construe legislation "with such modifications, adaptations, qualifications and exceptions as may be necessary to bring them into conformity with the constitution", the courts exercise a quasi-legislative power. This means that the courts are not only confined to interpreting the legislation, but may also exercise a power to modify and amend it to bring it into conformity with the Constitution. Their Lordships noted that in R. v. Hughes (2002)[71] the Privy Council had exercised a legislative power to delete express words in the impugned statute. Such an act is appropriate in a legal system where there is constitutional supremacy, and "[a] finding of inconsistency may leave a lacuna in the statute book which in many cases must be filled without delay if chaos is to be avoided and which can be filled only by the exercise of a legislative power".[72]

Applicability to laws in force prior to commencement of Constitution

In Review Publishing Co. Ltd. v. Lee Hsien Loong (2010),[73] the Court of Appeal rejected the appellant's claim that Article 105(1) of the Constitution of the State of Singapore 1963[74] (now Article 162) entailed that all existing laws should be adjusted to the Constitution. Instead, the Court held that the Article had the effect of re-enacting all existing laws at the date of commencement of the Constitution.[75] Thus, in essence, such existing laws remain in force after the Constitution's commencement as they amount to laws imposed by Parliament as a restriction on fundamental liberties such as the right to freedom of speech and expression guaranteed to citizens by Article 14(1)(a). Article 14(2)(a) states:

Parliament may by law impose — ... on the rights conferred by clause (1)(a), such restrictions as it considers necessary or expedient in the interest of the security of Singapore or any part thereof, friendly relations with other countries, public order or morality and restrictions designed to protect the privileges of Parliament or to provide against contempt of court, defamation or incitement to any offence ...

It appears that the Court of Appeal only applied the first limb of Article 162 ("all existing laws shall continue in force on and after the coming into operation of this Constitution"), and did not take into account the second limb ("all such laws shall ... be construed as from the commencement of this Constitution with such modifications, adaptations, qualifications and exceptions as may be necessary to bring them into conformity with this Constitution"). In contrast, the Privy Council in Director of Public Prosecutions v. Mollison (No. 2) (2003)[76] held that section 4 of the Jamaica (Constitution) Order in Council 1962,[77] which is similarly worded to Article 162, does not protect existing laws from constitutional challenge but "recognises that existing laws may be susceptible to constitutional challenge and accordingly confers power on the courts and the Governor General (among others) to modify and adapt existing laws so as 'to bring them into conformity with the provisions of this Order'".[78]

In any case, the Court of Appeal appears to have departed from the approach it adopted in Review Publishing. In Tan Eng Hong v. Attorney-General (2012),[79] it took the view that while the court does not have power under Article 162 to hold that laws inconsistent with the Constitution are entirely void,[80] a purposive reading of Articles 4 and 162 indicates that pre-commencement laws can be declared void under Article 4, even though that Article only refers specifically to laws enacted after the Constitution's commencement.[81]

Declarations

If an applicant wishes to contend that a public body's act or decision is inconsistent with the Constitution, the remedy requested is essentially a declaration, which has the effect of stating the law based on the facts before the court and establishes the legal position between the parties to the action.[82]

A declaration was sought in Chee Siok Chin v. Attorney-General (2006),[83] where the plaintiffs claimed that the repeal of O. 14, r. 1(2) of the Rules of the Supreme Court 1970[84] by way of the Rules of the Supreme Court (Amendment No. 2) Rules 1991 ("the 1991 amendment")[85] was unconstitutional and in breach of the principles of natural justice.[86] However, the assertion was held to be groundless as counsel for the plaintiffs had failed to identify exactly which part of the Constitution had been violated by the 1991 amendment and explain how the plaintiffs' constitutional rights had been abrogated. As such, no declaratory order was granted to render the amended O. 14 summary judgment procedure unconstitutional.[87]

Prospective overruling

Statutes and common law rules that are declared unconstitutional are void ab initio (from the beginning) – it is as if they never existed. This may create a problem as past cases decided on the basis of the unconstitutional legislation or precedent may be open to re-litigation. To overcome this problem, the Court of Appeal may apply the doctrine of prospective overruling to preserve the state of law prior to the date when the unconstitutional law is overruled.

The principle was set out by the Court of Appeal in Public Prosecutor v. Manogaran s/o R. Ramu (1996)[88] as follows:

[I]f a person organises his affairs in accordance with an existing judicial pronouncement about the state of the law, his actions should not be impugned retrospectively by a subsequent judicial pronouncement which changes the state of the law, without his having been afforded an opportunity to reorganise his affairs.

Manogaran was a criminal rather than a constitutional matter. The Court overruled an earlier decision, Abdul Raman bin Yusof v. Public Prosecutor (1996),[89] holding that the decision had incorrectly defined the term cannabis mixture in the Misuse of Drugs Act.[90] However, it held that the overruling should apply prospectively – in other words, the new definition of cannabis mixture should only apply to acts occurring after the date of the judgment, and the accused was entitled to rely on the law as stated in Abdul Raman.[91] In reaching this decision, the Court relied on the principle of nullem crimen nulla poena sine lege ("conduct cannot be punished as criminal unless some rule of law has already declared conduct of that kind to be criminal and punishable as such"), which it said was embodied in Article 11(1) of the Constitution:[92]

No person shall be punished for an act or omission which was not punishable by law when it was done or made, and no person shall suffer greater punishment for an offence than was prescribed by law at the time it was committed.

Prospective overruling is a remedy available in constitutional cases, as in Manogaran the Court noted that the doctrine had been developed in US jurisprudence to deal with the consequences of laws being declared unconstitutional.[93] It cited the United States Supreme Court decision Chicot County Drainage District v. Baxter State Bank (1940):[94]

The actual existence of a statute, prior to such a determination, is an operative fact and may have consequences which cannot justly be ignored. The past cannot always be erased by a new judicial declaration. ... [I]t is manifest from numerous decisions that an all-inclusive statement of a principle of absolute retroactive invalidity cannot be justified.

One limit to the doctrine's application is that it can only be applied by the Court of Appeal.[95]

The doctrine of prospective overruling was also applied in the case of Abdul Nasir bin Amer Hamsah v. Public Prosecutor (1997).[96] The Court of Appeal clarified that the sentence of life imprisonment did not mean imprisonment for 20 years as had been the understanding for some time, but rather imprisonment for the whole of the remaining period of a convicted person's natural life. However, if the judgment applied retrospectively, this would be unjust to accused persons already sentenced to life imprisonment as they would have been assured by lawyers and the Singapore Prison Service that they would only be incarcerated up to 20 years. Some accused persons might even have pleaded guilty on that understanding.[97] Thus, the Court held that its re-interpretation of the law would not apply to convictions and offences committed prior to the date of the judgment.[98]

Temporary validation of unconstitutional laws

Another remedy that Singapore courts might apply if an appropriate case arises – though it has yet to do so – is the granting of temporary validity to unconstitutional laws. When a piece of legislation is ruled as unconstitutional, a lacuna or gap in the law may ensue as the legislation is void retrospectively and prospectively. The situation is exacerbated if the legislation is one with far-reaching effects. Hence, to overcome the negative impact of such a lacuna, the Supreme Court of Canada has adopted the remedy of granting temporary validity to unconstitutional legislation for the minimum time necessary for the legislature to enact alternative laws.[99]

In the case of Reference re Manitoba Language Rights (1985),[99] the Official Language Act, 1890[100] purported to allow Acts of the Legislature of Manitoba to be published and printed only in English. The Supreme Court held that the Official Language Act was unconstitutional 95 years after it was passed, as it was inconsistent with section 23 of the Manitoba Act, 1870[101] (part of the Constitution of Canada) which requires Acts to be published in both English and French. The impact of such an outcome was that all laws of Manitoba which had not enacted in both English and French were never valid. These laws included, among others, laws governing persons' rights, criminal law, and even the laws pertaining to election of the Legislature.[102]

The remedy of temporary validation of unconstitutional laws was granted because the Supreme Court noted that if statutes enacted solely in English after the Manitoba Act were simply held void without more, the resulting absence of applicable laws would breach the rule of law. The Court also found support in the doctrine of state necessity, under which statutes that are unconstitutional can be treated as valid during a public emergency.[103] It referred to the case of Attorney-General of the Republic v. Mustafa Ibrahim (1964),[104] in which the Cyprus Court of Appeal held that four prerequisites are required before the state necessity doctrine can be invoked to validate an unconstitutional law: "(a) an imperative and inevitable necessity or exceptional circumstances; (b) no other remedy to apply; (c) the measure taken must be proportionate to the necessity; and (d) it must be of a temporary character limited to the duration of the exceptional circumstances".[105]

Remedies unavailable in constitutional law

Damages

The constitutions of some jurisdictions have clauses stating that the court may provide redress to those whose rights have been shown to be violated.[106] The Privy Council has held that such clauses empower the court to grant damages (monetary compensation) vindicating the constitutional right that has been contravened to "reflect the sense of public outrage, emphasise the importance of the constitutional right and the gravity of the breach, and deter further breaches".[107] However, no clause of this nature exists in the Singapore Constitution. Since in Singapore the granting of damages is outside the ambit of judicial review in administrative law,[108] the same is probably true for a breach of the Constitution. In order to claim damages, an aggrieved person must be able to establish a private law claim in contract or tort law.[109] Prior to May 2011, if prerogative orders had been applied for under O. 53 of the Rules of Court, such a person would have had to take out a separate legal action for damages. Now, it is possible for a person who has successfully obtained prerogative orders or a declaration to ask the High Court to also award him or her "relevant relief",[110] that is, a liquidated sum, damages, equitable relief or restitution.[111] The Court may give directions to the parties relating to the conduct of the proceedings or otherwise to determine whether the applicant is entitled to the relevant relief sought, and must allow any party opposing the granting of such relief an opportunity to be heard.[112]

If a claimant establishes that a public authority's wrongful action amounts to a tort, he or she may be able to obtain exemplary damages if it can be shown that the authority has been guilty of "oppressive, arbitrary or unconstitutional action" in the exercise of a public function.[113]

Injunctions

An injunction is a remedy having the effect of preventing the party to whom it is addressed from executing certain ultra vires acts. An injunction that is positive in nature may also be granted to compel performance of a particular act.[114] This remedy is not available in Singapore in relation to public law. The Government Proceedings Act[115] prevents the court from imposing injunctions or ordering specific performance in any proceedings against the Government. However, in place of such relief, the court may make an order declaratory of the rights between parties.[116]

Notes

- Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1985 Rev. Ed., 1999 Reprint).

- Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. Public Prosecutor [1994] ICHRL 26, [1994] SGHC 207, [1994] 3 S.L.R.(R.) [Singapore Law Reports (Reissue)] 209 at 231, para. 50, archived from the original on 26 October 2012, High Court (Singapore).

- Eng Foong Ho v. Attorney-General [2009] SGCA 1, [2009] 2 S.L.R. 542 at 550, para. 28, Court of Appeal (Singapore).

- Supreme Court of Judicature Act (Cap. 322, 2007 Rev. Ed.) ("SCJA"), s. 18(2) read with the 1st Sched., para. 1.

- Rules of Court (Cap. 322, R 5, 2006 Rev. Ed.) ("ROC"), O. 15, r. 16.

- Subordinate Courts Act (Cap. 321, 2007 Rev. Ed.) ("SCA"), s. 19(3)(b).

- As regards District Courts, see the SCA, ss. 19(3)(b); and as regards Magistrate's Courts, see s. 52(2).

- SCA, ss. 31(2)(b) and 52(1B)(b)(ii).

- SCA, s. 52(1A)(a).

- Johari bin Kanadi v. Public Prosecutor [2008] SGHC 62, [2008] 3 S.L.R.(R.) 422, H.C. (Singapore).

- Johari bin Kanadi, pp. 429–430, para. 9.

- Criminal Procedure Code 2010 (No. 15 of 2010) (now Cap. 68, 2012 Rev. Ed.) ("CPC").

- CPC, s. 430 read with the 6th Sched., para. 105.

- Section 395(1) of the CPC states that "[a] trial court hearing any criminal case, may on the application of any party to the proceedings or on its own motion, state a case to the relevant court on any question of law", and s. 395(2)(a) states that "[a]ny application or motion made ... on a question of law which arises as to the interpretation or effect of any provision of the Constitution may be made at any stage of the proceedings after the question arises". Section 395(15) defines relevant court as meaning the High Court when the trial court is a Subordinate Court.

- Chee Soon Juan v. Public Prosecutor [2011] SGHC 17, [2011] 2 S.L.R. 940, H.C. (Singapore).

- Chee Soon Juan, pp. 958–959, para. 33.

- CPC, s. 396(1).

- SCJA, ss. 20 and 21.

- Compare Peter Leyland; Gordon Anthony (2008), "The Remedies", Textbook on Administrative Law (6th ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 453–470 at 454, ISBN 978-0-19-921776-2.

- Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. Minister for Information and the Arts [1992] ICHRL 1, [1996] 1 S.L.R.(R.) 294, C.A. (Singapore) ("Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. MITA").

- Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. MITA, p. 309, para. 46.

- Compare Leyland & Anthony, p. 457.

- Re Fong Thin Choo [1991] 1 S.L.R.(R.) 774, H.C. (Singapore).

- Fong Thin Choo, p. 781, para. 17.

- Borissik v. Urban Redevelopment Authority [2009] SGHC 154, [2009] 4 S.L.R.(R.) 92 at 102, para. 21, H.C. (Singapore).

- Wong Keng Leong Rayney v. Law Society of Singapore [2006] SGHC 179, [2006] 4 S.L.R.(R.) 934 at 965, para. 79, H.C. (Singapore).

- Re Onkar Shrian [1968–1970] S.L.R.(R.) 533, H.C. (Singapore).

- Onkar Shrian, p. 538, para. 10, citing Lord Simonds, ed. (1952–1964), The Laws of England: Being a Complete Statement of the Whole Law of England: Crown Proceedings to Deeds and Other Instruments [Halsbury's Laws of England], 11 (3rd ed.), London: Butterworth & Co., p. 24, OCLC 494652904.

- See also Yeap Hock Seng @ Ah Seng v. Minister for Home Affairs, Malaysia [1975] 2 M.L.J. [Malayan Law Journal] 279 at 281, High Court (Malaysia): "Habeas corpus is a high prerogative writ of summary character for the enforcement of this cherished civil right of personal liberty and entitles the subject of detention to a judicial determination that the administrative order adduced as warrant for the detention is legally valid ..."

- H. F. Rawlings (1983), "Habeas Corpus and Preventive Detention in Singapore and Malaysia", Malaya Law Review, 25: 324–350 at 330.

- Chng Suan Tze v. Minister for Home Affairs [1988] SGCA 16, [1988] 2 S.L.R.(R.) 525, C.A. (Singapore), archived from the original on 24 December 2011.

- Internal Security Act (Cap. 143, 1985 Rev. Ed.).

- Chng Suan Tze, pp. 537–542, paras. 29–42.

- Chng Suan Tze, pp. 542–554, paras. 43–86.

- Bryan A. Garner, ed. (1999), "return", Black's Law Dictionary (7th ed.), St. Paul, Minn.: West, p. 1319, ISBN 978-0-314-24130-6,

A court officer's indorsement on an instrument brought back to the court, reporting what the officer did or found

; "return, n.", OED Online, Oxford: Oxford University Press, December 2011, retrieved 5 January 2012,The act, on the part of a sheriff, of returning a writ of execution to the court from which it was issued together with a statement of how far its instructions have been carried out. Hence: the report of a sheriff on any writ of execution received.

. - Habeas Corpus Act (56 Geo. 3, c. 100, UK).

- Chng Suan Tze, pp. 563–564, para. 120, citing Khera v. Secretary of State for the Home Department; Khawaja v. Secretary of State for the Home Department [1983] UKHL 8, [1984] A.C. 74 at 110, H.L. (UK) ("Khawaja") per Lord Scarman.

- The words represented by the first ellipsis were repealed by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1981 (c. 19, UK), Sch. 1 Pt. VIII.

- Andrew Phang (1994), "Cementing the Foundations: The Singapore Application of English Law Act 1993", University of British Columbia Law Review, 28 (1): 205–246 at 208.

- Application of English Law Act (Cap. 7A, 1994 Rev. Ed.) ("AELA").

- AELA, s. 4(1)(a) ("Subject to the provisions of this section and of any other written law, the following English enactments shall, with the necessary modifications, apply or continue to apply in Singapore: ... the English enactments specified in the second and third columns of the First Schedule to the extent specified in the fourth column thereof ..."), and s. 5(1) ("Except as provided in this Act, no English enactment shall be part of the law of Singapore."). See also Victor Yeo (April 1994), "Application of English Law Act 1993: A Step in the Weaning Process", Asia Business Law Review (4): 69–75 at 72.

- Lee Mau Seng v. Minister for Home Affairs [1971] SGHC 10, [1971–1973] S.L.R.(R.) 135 at 145, para. 17, H.C. (Singapore), archived from the original on 5 January 2012.

- Eshugbayi Eleko v. Government of Nigeria [1931] UKPC 37, [1931] A.C. 662, P.C. (on appeal from Nigeria).

- Eshugbayi Eleko, p. 670. See also the comment in the dissent of Lord Atkin in Liversidge v. Anderson [1941] UKHL 1, [1942] A.C. 206 at 245, H.L. (UK), "that in English law every imprisonment is prima facie unlawful and that it is for a person directing imprisonment to justify his act". Both Eshugbayi Eleko and Liversidge were cited in Khawaja, pp. 110–111. Lord Atkin's dissenting opinion was subsequently accepted as correct by the House of Lords in R. v. Inland Revenue Commissioners, ex parte Rossminster [1979] UKHL 5, [1980] A.C. 952 at 1011 and 1025, H.L. (UK). Compare Rawlings, pp. 344–345.

- Lau Lek Eng v. Minister for Home Affairs [1971–1973] S.L.R.(R.) 346 at 348–349, para. 9, H.C. (Singapore)

- Onkar Shrian, pp. 539–541, paras. 15–20.

- Khawaja, p. 111.

- ROC, O. 53, r. 1(2).

- Public Service Commission v. Lai Swee Lin Linda [2001] 1 S.L.R.(R.) 133, C.A. (Singapore).

- Lai Swee Lin Linda, p. 140, para. 20.

- ROC, O. 53, r. 1(6).

- UDL Marine (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. v. Jurong Town Corporation [2011] SGHC 45, [2011] 3 S.L.R. 94 at 106, paras. 35–37, H.C. (Singapore).

- ROC, O. 53, r. 2(1).

- Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. MITA, p. 298, para. 6.

- ROC, O. 53 r. 1(1).

- The Order does not apply to the Subordinate Courts: ROC, O. 54, r. 9.

- ROC, O. 54, rr. 1(2) and (3).

- Jeffrey Pinsler, ed. (2005), "Order 54: Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus", Singapore Court Practice 2005, Singapore: LexisNexis, pp. 1142–1144 at 1144, para. 54/1-9/2, ISBN 978-981-236-441-8.

- ROC, O. 54, r. 2.

- ROC, O. 54, r. 4.

- ROC, O. 54, r. 5.

- Khawaja, pp. 111–112.

- Rawlings, p. 343.

- Khawaja, pp. 113–114, citing Wright v. Wright [1948] HCA 33, (1948) 77 C.L.R. 191 at 210, High Court (Australia).

- Khawaja, p. 124. See also p. 128 per Lord Templeman.

- Constitution, Art. 2(1).

- Director of Public Prosecutions v. Hutchinson [1988] UKHL 11, [1990] 2 A.C. 783, House of Lords (UK).

- Hutchinson, p. 804.

- Hutchinson, p. 811.

- Ghaidan v. Godin-Mendoza [2004] UKHL 30, [2004] 2 A.C. 557, H.L. (UK).

- R v. Hughes [2002] UKPC 12, [2002] 2 A.C. 259, Privy Council (on appeal from Saint Lucia).

- Ghaidan, pp. 584–585, paras. 63–64.

- Review Publishing v. Lee Hsien Loong [2009] SGCA 46, [2010] 1 S.L.R. 52, C.A. (Singapore).

- Constitution of the State of Singapore 1963 in the Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore (State Constitutions) Order in Council 1963 (S.I. 1963 No. 1493, UK; reprinted as Gazette Notification (G.N.) Sp. No. S 1/1963), which was enacted under the Malaysia Act 1963 (1963 c. 35, UK), s. 4.

- Review Publishing, p. 168, para. 250.

- Director of Public Prosecutions v. Mollison (No. 2) [2003] UKPC 6, [2003] 2 A.C. 411, P.C. (on appeal from Jamaica).

- Jamaica (Constitution) Order in Council 1962 (S.I. 1962 No. 1550, UK), archived from the original Archived 2 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine on 2 November 2012.

- Mollison, p. 425, para. 15.

- Tan Eng Hong v. Attorney-General [2012] SGCA 45, [2012] 4 S.L.R. 476, C.A. (Singapore).

- See also Browne v. The Queen [1999] UKPC 21, [2000] 1 A.C. 45 at 50, P.C. (on appeal from Saint Christopher and Nevis).

- Tan Eng Hong, pp. 506–508, paras. 59–61.

- Leyland & Anthony, p. 461.

- Chee Siok Chin v. Attorney-General [2006] SGHC 153, [2006] 4 S.L.R.(R.) 541, H.C. (Singapore).

- Rules of the Supreme Court 1970 (Gazette Notification No. S 274/1970).

- Rules of the Supreme Court (Amendment No. 2) Rules 1991 (G.N. No. S 281/1991).

- Chee Siok Chin, p. 544, para. 1.

- Chee Siok Chin, p. 552, para. 22; and p. 555, para. 30.

- Public Prosecutor v. Manogaran s/o R. Ramu [1996] 3 S.L.R.(R.) 390 at 413, para. 74, C.A. (Singapore).

- Abdul Raman bin Yusof v. Public Prosecutor [1996] 2 S.L.R.(R.) 538, C.A. (Singapore).

- Misuse of Drugs (Cap. 185, 1985 Rev. Ed; now Cap. 185, 2008 Rev. Ed.).

- Manogaran, p. 416, para. 86.

- Manogaran, pp. 409–410, paras. 60–61.

- Manogaran, p. 412, para. 71.

- Chicot County Drainage District v. Baxter State Bank 308 U.S. 371, 374 (1940), Supreme Court (US), cited in Manogaran, p. 412, paras. 69–70.

- Manogaran, p. 416, para. 87.

- Abdul Nasir bin Amer Hamsah v. Public Prosecutor [1997] SGCA 38, [1997] 2 S.L.R.(R.) 842, C.A. (Singapore), archived from the original on 24 December 2011.

- Abdul Nasir, p. 855, para. 47.

- Abdul Nasir, p. 859, para. 60.

- Reference re Manitoba Language Rights, 1985 CanLII 33, [1985] 1 S.C.R. 721 at 782, 19 D.L.R. (4th) 1, Supreme Court (Canada). For commentary, see Peter W[ardell] Hogg (1989), "Necessity in a Constitutional Crisis: The Manitoba Language Rights Reference" (PDF), Monash University Law Review, 15 (3 & 4): 253–264.

- An Act to Provide that the English Language shall be the Official Language of the Province of Manitoba, 1890, c. 14 (Manitoba, Canada; reproduced on the Site for Language Management in Canada, Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute, University of Ottawa), archived from the original on 3 February 2013.

- Manitoba Act, 1870 (R.S.C. 1970; Manitoba, Canada).

- Manitoba Language Rights, paras. 54–58.

- Manitoba Language Rights, paras. 59–61, 83–85 and 105–106.

- Attorney-General of the Republic v. Mustafa Ibrahim [1964] Cyprus Law Reports 195, Court of Appeal (Cyprus), archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- Mustafa Ibrahim, p. 265, cited in Manitoba, para. 95.

- See, for example, s. 14(1) of the Trinidad and Tobago Constitution: "For the removal of doubts it is hereby declared that if any person alleges that any of the provisions of this Chapter has been, is being, or is likely to be contravened in relation to him, then without prejudice to any other action with respect to the same matter which is lawfully available, that person may apply to the High Court for redress by way of originating motion." Attorney General of Trinidad and Tobago v. Ramanoop [2005] UKPC 15, [2006] A.C. 328 at 334, para. 10, P.C. (on appeal from Trinidad and Tobago).

- Ramanoop, pp. 335–336, paras. 18–19.

- Borissik, p. 99, para. 22.

- Compare Leyland & Anthony, pp. 464–465.

- ROC, O. 53, r. 7(1).

- ROC, O. 53, r. 7(4).

- ROC, O. 53, rr. 7(2) and (3).

- Rookes v. Barnard [1964] UKHL 1, [1964] A.C. 1129, H.L. (UK), applied in Shaaban bin Hussien v. Chong Fook Kam [1969] UKPC 26, [1970] A.C. 942, P.C. (on appeal from Malaysia). See also Kuddus v. Chief Constable of Leicestershire Constabulary [2001] UKHL 29, [2002] 2 A.C. 122 at 144–145, para. 63, H.L. (UK).

- Leyland & Anthony, p. 458.

- Government Proceedings Act (Cap. 121, 1985 Rev. Ed.) ("GPA").

- GPA, ss. 2 and 27.

References

Cases

- Khera v. Secretary of State for the Home Department; Khawaja v. Secretary of State for the Home Department [1983] UKHL 8, [1984] A.C. 74, House of Lords (UK) ("Khawaja").

- Chng Suan Tze v. Minister for Home Affairs [1988] SGCA 16, [1988] 2 S.L.R.(R.) 525, Court of Appeal (Singapore), archived from the original on 24 December 2011.

- Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. Minister for Information and the Arts [1992] ICHRL 1, [1996] 1 S.L.R.(R.) 294, C.A. (Singapore) ("Chan Hiang Leng Colin v. MITA").

- Public Prosecutor v. Manogaran s/o R. Ramu [1996] 3 S.L.R.(R.) 390, C.A. (Singapore).

- Borissik v. Urban Redevelopment Authority [2009] SGHC 154, [2009] 4 S.L.R.(R.) 92, High Court (Singapore).

Legislation

- Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1985 Rev. Ed., 1999 Reprint).

- Rules of Court (Cap. 322, R 5, 2006 Rev. Ed.) ("ROC").

- Subordinate Courts Act (Cap. 321, 2007 Rev. Ed.) ("SCA").

- Supreme Court of Judicature Act (Cap. 322, 2007 Rev. Ed.) ("SCJA").

Other works

- Leyland, Peter; Anthony, Gordon (2008), "The Remedies", Textbook on Administrative Law (6th ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 453–470, ISBN 978-0-19-921776-2.

- Rawlings, H. F. (1983), "Habeas Corpus and Preventive Detention in Singapore and Malaysia", Malaya Law Review, 25: 324–350.

Further reading

Articles

- Bingham, T[homas] H[enry] (1991), "Should Public Law Remedies be Discretionary?", Public Law: 64–75.

- Huang, Su Mien (July 1960), "Judicial Review of Administrative Action by the Prerogative Orders", University of Malaya Law Review, 2 (1): 64–82.

- Kolinsky, Daniel (December 1999), "Advisory Declarations: Recent Developments", Judicial Review, 4 (4): 225–230, doi:10.1080/10854681.1999.11427082.

- Oliver, [A.] Dawn (January 2002), "Public Law Procedures and Remedies – Do We Need Them?", Public Law: 91–110.

- Tan, John Chor-Yong (December 1960), "Habeas Corpus in Singapore", University of Malaya Law Journal, 2 (2): 323–334.

About Singapore

- Cremean, Damien J. (2011), "Judicial Control of Administrative Action [ch. XIX]", M.P. Jain's Administrative Law of Malaysia and Singapore (4th ed.), Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia: LexisNexis, pp. 585–681, ISBN 978-967-4-00037-0.

- Tan, Kevin Y[ew] L[ee]; Thio, Li-ann (2010), "The Judiciary", Constitutional Law in Malaysia and Singapore (3rd ed.), Singapore: LexisNexis, pp. 505–630 at 559–573, ISBN 978-981-236-795-2.

- Tan & Thio, "Rights of the Accused Person", in Constitutional Law in Malaysia and Singapore, pp. 795–838 at 795–814.

About other jurisdictions

- Cane, Peter (1997), "The Constitutional Basis of Judicial Remedies in Public Law", in Leyland, Peter; Woods, Terry (eds.), Administrative Law Facing the Future: Old Constraints and New Horizons, London: Blackstone Press, pp. 242–270, ISBN 978-1-85431-689-9.

- Hogg, Peter W[ardell] (2007), "Effect of Unconstitutional Law [ch. 58]", Constitutional Law of Canada, 2 (5th ed.), pp. 745–770, ISBN 978-0-7798-1361-2.

- Lewis, Clive (2009), Judicial Remedies in Public Law (4th ed.), London: Sweet & Maxwell, ISBN 978-1-84703-221-8.

- Lord Woolf; Woolf, Jeremy (2011), Zamir & Woolf: The Declaratory Judgment (4th ed.), London: Sweet & Maxwell, ISBN 978-0-414-04135-6.