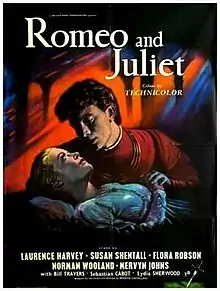

Romeo and Juliet (1954 film)

Romeo and Juliet is a 1954 film adaptation of William Shakespeare's play of the same name. It was directed by Renato Castellani and stars Laurence Harvey as Romeo, Susan Shentall as Juliet, Flora Robson as the Nurse, Mervyn Johns as Friar Laurence, Bill Travers as Benvolio, Sebastian Cabot as Lord Capulet, Ubaldo Zollo as Mercutio, Enzo Fiermonte as Tybalt and John Gielgud as the Chorus.

| Romeo and Juliet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Renato Castellani |

| Produced by | |

| Written by | |

| Based on | Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Roman Vlad |

| Cinematography | Robert Krasker |

| Edited by | Sidney Hayers |

| Distributed by | Rank Organisation (UK) |

Release date | 1 September 1954 (UK) 25 November 1954 (Italy) |

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | English Italian |

The film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and was named the best foreign film by the National Board of Review, which also named Castellani as best director.

Production

Joan Collins was originally announced to play Juliet.[1]

Critical attention

Renato Castellani won the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival for his 1954 film of Romeo and Juliet.[2] His film contains interpolated scenes intended to establish the class system and Catholicism of Renaissance Verona, and the nature of the feud. Some of Castellani's changes have been criticised as ineffective: interpolated dialogue is often banal, and the Prince's appearances are reimagined as formal hearings, undermining the spontaneity of Benvolio's defence of Romeo's behaviour in the duel scene.[3]

The major supporting roles are vastly reduced, including that of the nurse; Mercutio becomes (in the words of Daniel Rosenthal) "the tiniest of cameos", as does Tybalt, and Friar Laurence "an irritating ditherer",[4] although Pauline Kael, who admired the film, praised Mervyn Johns's performance, claiming that he transformed the Friar from a tiresome presence to "a radiantly silly little man".[5] Castellani's most prominent changes related to Romeo's character, cutting back or removing scenes involving his parents, Benvolio and Mercutio in order to highlight Romeo's isolation, and inserting a parting scene in which Montague coldly pulls his banished son out of Lady Montague's farewell embrace.[3]

Another criticism made by film scholar Patricia Tatspaugh is that the realism of the settings, so carefully established throughout the film, "goes seriously off the rails when it come to the Capulets' vault".[3] Castellani uses competing visual images in relation to the central characters: ominous grilles (and their shadows) contrasted with frequent optimistic shots of blue sky.[6] The fatal encounter between Romeo and Tybalt is here not an actual fight; the enraged Romeo simply rushes up to Tybalt and stabs him, taking him by surprise.

A well-known stage Romeo, John Gielgud, played Castellani's chorus (and would reprise the role in the 1978 BBC Shakespeare version). Laurence Harvey, as Romeo, was already an experienced screen actor, who would shortly take over roles intended for the late James Dean in Walk on the Wild Side and Summer and Smoke.[7] By contrast, Susan Shentall, as Juliet, was a secretarial student who was discovered by the director in a London pub, and was cast for her "pale sweet skin and honey-blonde hair."[8] She surpassed the demands of the role, but married shortly after the shoot, and never returned to the screen.[8][4]

Other parts were played by inexperienced actors, also: Mercutio was played by an architect, Montague by a gondolier from Venice, and the Prince by a novelist.[4]

Critics responded to the film as a piece of cinema (its visuals were especially admired in Italy, where it was filmed) but not as a performance of Shakespeare's play: Robert Hatch in The Nation said "We had come to see a play... perhaps we should not complain that we were shown a sumptuous travelogue", and Time′s reviewer added that "Castellani's Romeo and Juliet is a fine film poem... Unfortunately it is not Shakespeare's poem!"[9]

Commercially response to the film was underwhelming. One journalist described it as the "unchallenged flop of the year".[10]

References

Notes

- "British films lifted out of doldrums for the Coronation". The Australian Women's Weekly. National Library of Australia. 4 March 1953. p. 29. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- Tatspaugh 2000, p. 138.

- Tatspaugh 2000, p. 139.

- Rosenthal 2007, pp. 213–14.

- Kael 1991, p. 639.

- Tatspaugh 2000, p. 140.

- Brode 2001, pp. 48–9.

- Brode 2001, p. 51.

- Brode 2001, pp. 50–1.

- "Our "Zither Girl" had no hope". The Sunday Times. Perth: National Library of Australia. 19 December 1954. p. 39. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

Sources

- Brode, Douglas (2001). Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Today. New York: Berkeley Boulevard. ISBN 0-425-18176-6.

- Kael, Pauline (1991). 5001 Nights at the Movies. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8050-1367-2.

- Rosenthal, Daniel (2007). 100000. BFI Screen Guides. London: British Film Institute. ISBN 978-1-84457-170-3.

- Tatspaugh, Patricia (2000). "The Tragedy of Love on Film". In Jackson, Russell (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63975-1.