SMS Deutschland (1904)

SMS Deutschland (His Majesty's Ship Germany)[lower-alpha 1] was the first of five Deutschland-class pre-dreadnought battleships built for the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). The ship was armed with a main battery of four 28 cm (11 in) guns in two twin turrets. She was built at the Germaniawerft shipyard in Kiel, where she was laid down in June 1903 and launched in November 1904. She was commissioned on 3 August 1906, a few months ahead of HMS Dreadnought. The latter, armed with ten large-caliber guns, was the first of a revolutionary new standard of "all-big-gun" battleships that rendered Deutschland and the rest of her class obsolete.

SMS Deutschland in the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal in 1912 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Deutschland |

| Namesake: | Germany (Deutschland in German) |

| Builder: | Germaniawerft, Kiel |

| Laid down: | 20 June 1903 |

| Launched: | 19 November 1904 |

| Commissioned: | 3 August 1906 |

| Stricken: | 25 January 1920 |

| Fate: | Scrapped in 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Deutschland-class battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 127.6 m (418 ft 8 in) |

| Beam: | 22.2 m (72 ft 10 in) |

| Draft: | 8.21 m (26 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 3 triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range: | 4,850 nmi (8,980 km; 5,580 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

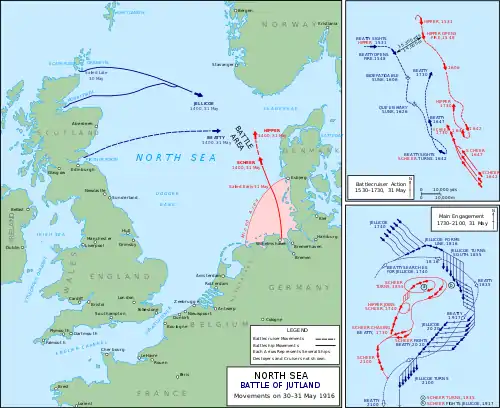

Deutschland served as the flagship of the High Seas Fleet until 1913, when she was transferred to II Battle Squadron. With the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, she and her sister ships were tasked with defending the mouth of the Elbe and the German Bight from possible British incursions. Deutschland and the other ships of II Battle Squadron participated in most of the large-scale fleet operations in the first two years of the war, culminating in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916. Late on the first day of the battle, Deutschland and the other pre-dreadnoughts briefly engaged several British battlecruisers before retreating.

After the battle, in which pre-dreadnoughts proved too vulnerable against more modern battleships, Deutschland and her three surviving sisters were assigned to coastal defense duties. By 1917, they had been withdrawn from combat service completely, disarmed, and tasked with auxiliary roles. Deutschland was used as a barracks ship in Wilhelmshaven until the end of the war. She was struck from the naval register on 25 January 1920, sold to ship breakers that year, and broken up for scrap by 1922.

Design

The passage of the Second Naval Law in 1900 under the direction of Vizeadmiral (VAdm—Vice Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz secured funding for the construction of twenty new battleships over the next seventeen years. The first group, the five Braunschweig-class battleships, were laid down in the early 1900s, and shortly thereafter design work began on a follow-on design, which became the Deutschland class. The Deutschland-class ships were broadly similar to the Braunschweigs, featuring incremental improvements in armor protection. They also abandoned the gun turrets for the secondary battery guns, moving them back to traditional casemates to save weight.[1][2] The British battleship HMS Dreadnought—armed with ten 12-inch (30.5 cm) guns—was commissioned in December 1906.[3] Dreadnought's revolutionary design rendered every capital ship of the German navy obsolete, including Deutschland.[4]

Deutschland was 127.6 m (418 ft 8 in) long overall, with a beam of 22.2 m (72 ft 10 in), and a draft of 8.21 m (26 ft 11 in). She displaced 13,191 metric tons (12,983 long tons) at normal loading, and up to 14,218 metric tons (13,993 long tons) at full loading. The ship was equipped with two heavy military masts. Her crew numbered 35 officers and 708 enlisted men.[5] Powered by three triple expansion steam engines that each drove a screw propeller, Deutschland was capable of a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) from 15,781 indicated horsepower (11,768 kW). Twelve coal-fired Scotch marine boilers provided steam for the engines; three funnels vented smoke from burning coal in the boilers. Deutschland had a fuel capacity of up to 1,540 metric tons (1,520 long tons; 1,700 short tons) of coal. At a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), she could steam for 4,850 nautical miles (8,980 km; 5,580 mi).[5]

Deutschland's primary armament consisted of four 28 cm (11 in) SK L/40 guns in two twin turrets.[lower-alpha 2] Her offensive armament was rounded out with fourteen 17 cm (6.7 in) SK L/40 guns mounted individually in casemates. A battery of twenty 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 guns in single mounts provided defense against torpedo boats. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she was also equipped with six 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, which were in the submerged part of the hull.[7] Krupp cemented armor protected the ship. Her armored belt was 140 to 225 millimeters (5.5 to 8.9 in) thick. Heavy armor amidships protected her magazines and machinery spaces, while thinner plating covered the ends of the hull. Her main-deck armor was 40 mm (1.6 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 280 mm (11 in) of armor plating.[5]

Service history

Construction through 1908

Deutschland was the second naval vessel to bear that name—after the 1874 armored frigate Deutschland. The modern ship was intended to fight in the German battle line with other battleships of the Imperial German Navy.[8] She was laid down on 20 July 1903 at the Germaniawerft dockyard in Kiel,[1] and launched on 19 November 1904. Her trials lasted from 3 August 1906 until the end of September. Deutschland replaced the battleship Kaiser Wilhelm II as the flagship of the Active Battle Fleet on 26 September, when Admiral Prince Heinrich hoisted his flag aboard. Her first commander was Kapitän zur See (KzS—Captain at Sea) Wilhelm Becker, though he served aboard the ship for just a month and was replaced by KzS Günther von Krosigk in September. She was tactically assigned to II Battle Squadron, displacing the older battleship Weissenburg,[9] though as the fleet flagship she was not subordinate to the squadron commander.[10] Prince Heinrich was new to the command, and he set about to train the fleet, with an emphasis on accurate gunfire and maneuvering as a unit.[11]

She took part in training exercises in the North Sea, in December 1906, before returning to Kiel. On 16 February 1907, the fleet was renamed the High Seas Fleet.[10] Fleet maneuvers in the North Sea followed, in early 1907, with a cruise to Skagen, Denmark, followed by mock attacks on the main naval base at Kiel.[11] Further exercises followed in May–June. In June, a cruise to Norway followed the fleet training. After returning from Norway, Deutschland went to Swinemünde in early August, where Czar Nicholas II of Russia met the German fleet in his yacht Standart. Afterward, the fleet assembled for the annual autumn fleet maneuvers, held with the bulk of the fleet every August and September. This year, the maneuvers were delayed to allow for a large fleet review, including 112 warships, for Kaiser Wilhelm II in the Schillig roadstead. In the autumn maneuvers that followed, the fleet conducted exercises in the North Sea and then joint maneuvers with IX Army Corps around Apenrade. Deutschland returned to Kiel on 14 September, after the conclusion of the maneuvers. In November, she took part in unit training in the Kattegat,[12] before she was taken into dry-dock for an annual refit.[13]

In February 1908, Deutschland participated in fleet maneuvers in the Baltic Sea. With Wilhelm II aboard, she was present for the launch of the first German dreadnought battleship, Nassau, on 7 March, and afterward carried the Kaiser to visit the island of Helgoland in the German Bight, accompanied by the light cruiser Berlin. In May–June, fleet training was conducted off Helgoland; Crown Prince Wilhelm, the Kaiser's son, observed the exercises aboard Deutschland. In July 1908, Deutschland and the rest of the fleet sailed into the Atlantic Ocean to conduct a major training cruise. Prince Heinrich had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing Anglo-German naval arms race were high. The fleet departed Kiel on 17 July, passed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal to the North Sea, and continued to the Atlantic. During the cruise, Deutschland stopped at Funchal, Portugal and Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands. The fleet returned to Germany on 13 August. The autumn maneuvers followed from 27 August to 12 September. Later that year, the fleet toured coastal German cities as part of an effort to increase public support for naval expenditures.[14]

1909–1914

The next year—1909—followed much the same pattern. KzS Ehler Behring replaced von Krosigk in April. In June, Deutschland won the Kaiser's Schießpreis (Shooting Prize) for excellent shooting in II Squadron. Another cruise into the Atlantic was conducted from 7 July to 1 August, during which Deutschland stopped in Bilbao, Spain. While on the way back to Germany, the High Seas Fleet was received by the British Royal Navy in Spithead.[15] After another round of exercises, Deutschland went in for a periodic overhaul. During the refit, she was given additional pedestal-mounted searchlights and became the first ship in the German navy to be equipped with an X-ray machine.[13] In late 1909, Prince Heinrich was replaced by Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, who kept Deutschland as his flagship. Holtzendorff's tenure as fleet commander was marked by strategic experimentation, owing to the increased threat the latest underwater weapons posed and the fact that the new Nassau-class battleships were too wide to pass through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. Accordingly, the fleet was transferred from Kiel to Wilhelmshaven on 1 April 1910.[16]

In May 1910, the fleet conducted training maneuvers in the Kattegat. These were in accordance with Holtzendorff's strategy, which envisioned drawing the Royal Navy into the narrow waters there. The annual summer cruise was to Norway, and was followed by fleet training, during which another fleet review was held in Danzig on 29 August. Deutschland again won the Schießpreis that year.[17] In November, Deutschland, accompanied by the aviso Hela and the dispatch boat Sleipner, hosted Wilhelm II during the celebration of the opening of the Naval Academy Mürwik in Flensburg. Deutschland had too deep a draft to enter Gelting Bay outside the Flensburg Firth, so Wilhelm II transferred to Sleipner. A training cruise into the Baltic followed at the end of the year.[16] In early March 1911, Deutschland again carried Wilhelm II to Helgoland; this trip was followed by fleet exercises in the Skagerrak and Kattegat that month. Deutschland and the rest of the fleet received British and American naval squadrons at Kiel in June and July. The year's autumn maneuvers were confined to the Baltic and the Kattegat, and Deutschland won the Schießpreis a third time. Another fleet review was held during the exercises for a visiting Austro-Hungarian delegation that included Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli. Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, the Chancellor of Germany, also attended the review, aboard Deutschland. On 1 October, Deutschland was relieved of her tactical assignment to II Squadron, as the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) authorized the fleet to keep a 17th battleship in commission—I and II Squadrons comprising eight battleships each, so the fleet could now keep two full squadrons in addition to the flagship.[18][8]

In mid-1912, due to the Agadir Crisis, the summer cruise was confined to the Baltic, to avoid exposing the fleet during the period of heightened tension with Britain and France. In September, following the autumn maneuvers, Deutschland suffered a grounding while in the Baltic. The resulting damage necessitated dry-docking, and repairs were completed by November, allowing the ship to take part in the winter cruise in the Baltic.[13][19] In October, during the repair period, KzS Hugo Meurer took command of the ship.[20] On 30 January 1913, Holtzendorff was relieved as the fleet commander, owing in large part due to Wilhelm II's displeasure with his strategic vision. VAdm Friedrich von Ingenohl took Holtzendorff's place that day; but only one day later, on the 31st, he lowered his flag aboard Deutschland to transfer to the new dreadnought Friedrich der Grosse, which replaced Deutschland as flagship. The golden bow ornament that denoted the flagship was removed, and Deutschland returned to the ranks of II Battle Squadron. The year's training proceeded in much the same pattern as in previous years. Deutschland briefly resumed flagship duties in late 1913, as Friedrich der Grosse was in dry-dock for periodic maintenance.[21][22]

World War I

On 14 July 1914, the annual summer cruise to Norway began. The threat of war during the July Crisis caused Kaiser Wilhelm II to end the cruise early, after only two weeks; and by the end of July the fleet was back in port.[23] Deutschland reached Kiel on the 29th, and moved to Wilhelmshaven on 1 August. With the outbreak of war, Deutschland and the rest of II Squadron was tasked with coastal defense at the mouth of the Elbe. This duty was interrupted from 2 to 23 October, when the ship returned to Wilhelmshaven, and from 27 October to 4 November, for an overhaul in Kiel. On 10 November, she took part in a sweep into the Baltic toward Bornholm, which concluded uneventfully two days later. By 17 November, the ship was again stationed off the coast near the Elbe.[24] While her sisters covered the raid on the English coast on 15–16 December, Deutschland remained on picket duty at the mouth of the Elbe.[21]

Deutschland returned to Wilhelmshaven on 21 January, where, two days later, Ingenohl temporarily made the ship his flagship while Friedrich der Grosse was transferred to the Baltic for training exercises. During this period, the Battle of Dogger Bank took place, where the German armored cruiser Blücher was sunk and the battleships of the High Seas Fleet failed to intervene. Ingenohl, who had returned to Friedrich der Grosse on 1 February, was relieved of command and replaced by VAdm Hugo von Pohl. Deutschland returned to her coastal patrol duties off the Elbe. On 21 February 1915, Deutschland went into dock in Kiel, where work lasted until 12 March. Afterward, Deutschland returned to the Elbe for guard duty, and on 14 March she became the II Squadron flagship under Konteradmiral (KAdm—Rear Admiral) Felix Funke, though he was replaced by KAdm Franz Mauve on 12 August. On 21 September, the ship went to the Baltic for training, which was completed by 11 October, after which she went into the dockyard in Kiel again for maintenance.[21][24]

Coastal defense duty continued into early 1916. Deutschland was transferred to the AG Vulcan dry-dock in Hamburg for further maintenance that took place from 27 February to 1 April 1916. On 24–25 April 1916, Deutschland and her four sisters joined the dreadnoughts of the High Seas Fleet—which was now commanded by VAdm Reinhard Scheer—to support the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group on a raid of the English coast.[21] En route to the target, the battlecruiser Seydlitz was damaged by a mine; she was detached to return home while the operation proceeded. The battlecruisers conducted a short bombardment of the ports of Yarmouth and Lowestoft. Visibility was poor, and the operation was called off before the British fleet could intervene.[25] On 4 May, Deutschland took part in a sortie against British ships off Horns Reef, without result.[21] Squadron exercises in the Baltic followed from 11 to 22 May.[24]

Battle of Jutland

Scheer immediately planned another foray into the North Sea, but the damage to Seydlitz delayed the operation until the end of May.[26] II Battle Squadron—possessing the weakest battleships involved in the battle, and under-strength owing to the absence of Pommern, guarding the mouth of the Elbe, and Lothringen, worn out and removed from active service—was positioned at the rear of the German line.[27][28] Shortly before 16:00 the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group encountered the British 1st Battlecruiser Squadron under the command of David Beatty. The opposing ships began an artillery duel that resulted the destruction of HMS Indefatigable, shortly after 17:00,[29] and HMS Queen Mary, less than half an hour later.[30] By this time, the German battlecruisers were steaming south to draw the British ships toward the main body of the High Seas Fleet. Upon realizing that the German fleet was coming into range, Beatty turned his ships back toward the Grand Fleet. Scheer ordered the fleet to pursue the retreating battleships of the British 5th Battle Squadron at top speed. Deutschland and the other pre-dreadnoughts were significantly slower than the dreadnoughts, and quickly fell behind.[31] By 19:30, the Grand Fleet had arrived on the scene and confronted Scheer with significant numerical superiority.[32] The German fleet's maneuverability was severely hampered by the presence of the pre-dreadnoughts; if Scheer ordered an immediate turn towards Germany, he would have to sacrifice the slower ships to make good his escape.[33]

Scheer reversed the course of the fleet via a Gefechtskehrtwendung (battle about turn), a maneuver that required every unit in the German line to turn 180° simultaneously.[34] Having fallen behind, the ships of II Battle Squadron could not conform to the new course following the turn.[35] Deutschland and the other five ships of the squadron were therefore on the disengaged side of the German line. Mauve considered moving his ships to the rear of the line, astern of the III Battle Squadron dreadnoughts, but decided against it when he realized the movement would interfere with the maneuvering of Admiral Franz von Hipper's battlecruisers. Instead, he attempted to place his ships at the head of the line.[36] Later in the day, the hard-pressed battlecruisers of I Scouting Group were being pursued by their British counterparts. Deutschland and the other so-called "five-minute ships"[lower-alpha 3] came to their aid by steaming between the opposing battlecruiser squadrons.[38] Poor visibility made the subsequent engagement brief. Deutschland fired only one round from her 28 cm guns during this period.[38] Mauve decided it would be inadvisable to continue the fight against the much more powerful battlecruisers, and so ordered an 8-point turn to starboard.[39]

Late on the 31st, the fleet organized for the night march back to Germany; Deutschland, Pommern, and Hannover fell in behind König and the other dreadnoughts of III Battle Squadron towards the rear of the line.[40] British destroyers conducted a series of attacks against the fleet, some of which targeted Deutschland. In the melee, Deutschland and König turned away from the attacking destroyers, but could not make out targets clearly enough to engage them effectively,[41] Deutschland firing only a few 8.8 cm shells in the mist without effect.[42] Soon after, Pommern exploded after she was struck by at least one torpedo. Fragments of the ship rained down around Deutschland.[43] Regardless, the High Seas Fleet punched through the British destroyer forces and reached Horns Reef by 4:00 on 1 June.[44] The German fleet reached Wilhelmshaven a few hours later, where the undamaged dreadnoughts of the Nassau and Helgoland classes took up defensive positions while the damaged ships and the survivors of II Squadron retreated within the harbor.[45] In the course of the battle, Deutschland had expended only a single 28 cm shell and five 8.8 cm rounds. She had not been damaged in the engagement.[46]

Final operations

After Jutland, Deutschland and her three surviving sisters returned to picket duty at the mouth of the Elbe. They were also occasionally transferred for guard duty in the Baltic.[21] The experience at Jutland demonstrated that pre-dreadnoughts had no place in a naval battle with dreadnoughts, and they were thus left behind when the High Seas Fleet sortied again on 18 August.[28] In July, KzS Rudolf Bartels replaced Meurer as the ship's captain; he held the position for just a month, before he was in turn replaced by Deutschland's final commander, KzS Reinhold Schmidt.[20] In late 1916, the ships of II Squadron were removed from the High Seas Fleet. From 22 December 1916 to 16 January 1917, Deutschland lay idle in the Bay of Kiel. On 24 January, the ship was taken to Hamburg where she went into the dry-dock for maintenance; this work lasted until 4 April.[28] During this period in the shipyard, Deutschland had her forwardmost pair of 8.8 cm guns in the aft superstructure removed and two 8.8 cm guns in anti-aircraft mountings were installed.[47]

Deutschland sailed out of the Altenbruch roads at the mouth of the Elbe on 28 July and then to the Baltic for continued guard duty. During this period, she briefly served as the flagship of the coastal defense command in the western Baltic, though on 10 September the cruiser Stettin replaced her.[21][28] On 15 August, II Battle Squadron was disbanded. Two weeks later, on 31 August, Deutschland arrived in Kiel. She was decommissioned on 10 September. Deutschland then had her guns removed before she was transferred to Wilhelmshaven to serve as a barracks ship.[21][28] Many of her guns were converted for use ashore, either as coastal artillery, field guns, or railway guns.[48] On 25 January 1920 the ship was struck from the naval register and sold for scrapping, which was completed by 1922. The ship's bow ornament is on display at the Eckernförde underwater weapons school, and her bell is in the mausoleum of Prince Heinrich at the Hemmelmark estate.[49]

Footnotes

Notes

- "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German.

- In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick loading, while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 caliber, meaning that the gun is 40 times as long as it is in diameter.[6]

- The ships were called "five-minute ships" because that was the length of time they were expected to survive if confronted by a dreadnought.[37]

Citations

- Staff, p. 5.

- Hore, p. 69.

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 21–22.

- Herwig, p. 57.

- Gröner, p. 20.

- Grießmer, p. 177.

- Staff, p. 6.

- Herwig, p. 45.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 235–236.

- Staff, p. 7.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 237.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 237–238.

- Staff, p. 8.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 238.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 235, 238.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 240–241.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 240.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 241–242.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 242.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 235.

- Staff, p. 10.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 243–244.

- Staff, p. 11.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 244.

- Tarrant, pp. 52–54.

- Tarrant, p. 58.

- Tarrant, p. 286.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 245.

- Tarrant, pp. 94–95.

- Tarrant, pp. 100–101.

- London, p. 73.

- Tarrant, p. 150.

- Tarrant, pp. 150–152.

- Tarrant, pp. 152–153.

- Tarrant, p. 154.

- Tarrant, p. 155.

- Tarrant, p. 62.

- Tarrant, p. 195.

- Tarrant, pp. 195–196.

- Tarrant, p. 241.

- Tarrant, p. 242.

- Campbell, p. 299.

- Tarrant, p. 243.

- Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- Tarrant, p. 263.

- Campbell, pp. 348, 359.

- Dodson, p. 54.

- Friedman, p. 143.

- Gröner, p. 22.

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Dodson, Aidan (2014). Jordan, John; Dent, Stephen (eds.). "Last of the Line: The German Battleships of the Braunschweig and Deutschland Classes". Warship 2014. London: Conway Maritime Press: 49–69. ISBN 978-1-59114-923-1.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien: ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart (Band 2) [The German Warships: Biographies: A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present (Volume 2)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0287-9.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- London, Charles (2000). Jutland 1916: Clash of the Dreadnoughts. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-992-8.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. 1: Deutschland, Nassau and Helgoland Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

Further reading

- Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2001). Die Panzer- und Linienschiffe der Brandenburg-, Kaiser Friedrich III-, Wittlesbach-, Braunschweig- und Deutschland-Klasse [The Armored and Battleships of the Brandenburg, Kaiser Friedrich III, Wittelsbach, Braunschweig, and Deutschland Classes] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-6211-8.