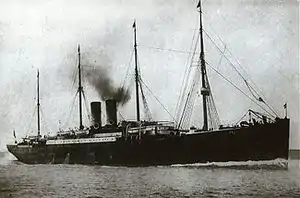

SS Elbe (1881)

SS Elbe was a transatlantic ocean liner built in the Govan Shipyard of John Elder & Company, Ltd, Glasgow, in 1881 for the Norddeutscher Lloyd of Bremen.[2] She foundered on the night of 30 January 1895 following a collision in the North Sea with the loss of 334 lives.

SS Elbe | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | SS Elbe[1] |

| Owner: | Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen |

| Ordered: | 1880 |

| Builder: | Messrs John Elder & Co., Govan, Glasgow, Scotland |

| Launched: | 2 April 1881 |

| In service: | 26 June 1881 |

| Refit: | 1890 |

| Homeport: | Bremen |

| Fate: | Sunk in the North Sea after collision, 31 January 1895 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 4,510 gross tons |

| Length: | 416.5 ft (126.9 m) |

| Beam: | 45 ft (14 m) |

| Propulsion: | 3 cylinder compound engine single propeller |

| Speed: | 15 knots |

| Complement: | 179 First Class, 142 Second Class 796 Third Class or steerage |

Construction and early history

The Elbe had a 3-cylinder compound engine which provided power to her single-screw propeller. She was a fast ship for her time, being able to reach the speed of 15 knots, but small cargo capacity, along with her high consumption of coal, would soon make her uneconomical. She had a straight bow, two funnels and four masts.[3] She was launched on 2 April 1881, the first of a series of eleven express steamers known as the "Rivers Class", as they were all named after German rivers. After sea trials she made her maiden voyage on 26 June 1881, leaving Bremen for New York City via Southampton. The Elbe had accommodation for 179 First Class passengers, 142 in Second Class, and 796 in Steerage. She was a very popular ship with immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe to the United States and was virtually always sold out in steerage. The Elbe spent most of the next ten years working the North Atlantic service, but she also made three voyages to Adelaide in Australia, two of which were in December 1889 and 1890.

Disaster in the North Sea

The night of 30 January 1895 was stormy.[4] In the North Sea, conditions were freezing and there were huge seas. SS Elbe had left Bremerhaven for New York earlier in the day with 354 passengers aboard. Also at sea on this rough night was the steamship Crathie, sailing from Aberdeen in Scotland, heading for Rotterdam. As conditions grew worse, the Elbe discharged warning rockets to alert other ships to her presence. The Crathie either did not see the warning rockets or chose to ignore them. She did not alter her course, with such disastrous consequences, that she struck the liner on her port side with such force that whole compartments of the Elbe were immediately flooded. The collision happened at 5.30 am and most of the passengers were still asleep. The Elbe began to sink immediately and the captain, von Goessel, gave the order to abandon ship. Amid great scenes of panic the crew managed to lower two of the Elbe's lifeboats. One of the lifeboats capsized as too many passengers tried in vain to squeeze into the boat. Twenty people scrambled into the second lifeboat, of whom 15 were members of the crew. The others were four male second-class passengers and a young lady’s maid by the name of Anna Boecker, who had been lucky enough to be pulled from the raging sea after the first boat had capsized. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Elbe, Captain von Goessel had ordered all the women and children to assemble there but no other lifeboats were launched because the ropes on the derricks were all frozen up, and so they perished along with the captain. Within 20 minutes of the collision, the Elbe had sunk and the only survivors were the 20 people in the one surviving lifeboat. These people now had to endure mountainous seas and below-zero temperatures and they were 50 miles from land. Things looked bleak; the Elbe's distress rockets had not been seen by any passing vessels and so no one knew of their predicament. After five hours in the raging storm, their luck changed. A fishing smack from Lowestoft called the Wildflower found them. In desperate conditions the crew of the Wildflower struggled to pull the 20 survivors from the lifeboat, which had begun to break up. The skipper, William Wright, said later that the survivors would not have lasted another hour in those conditions, and believed that the only reason they had stayed alive for five hours was the expertise of the Elbe's crewmen aboard the lifeboat.

Steamship Crathie

The Crathie was a steamer of about 475 tons gross and 272 net. She left Rotterdam with general cargo for Aberdeen on 29 January 1895 carrying just 12 hands. The Craithie was also badly damaged in the collision and returned to Rotterdam flying signals of distress. When later asked why they had not stayed on to help the Elbe and her passengers, the captain, Alexander Gordon, said that he feared that his ship would sink, and in any case he did not hear any cries for help coming from the liner. It appeared to him that the Elbe was steaming away from his position.[5]

Miss Anna Boecker

Of the twenty who survived the sinking, only one was a female. Anna Boecker[6] was a shy, quiet maid in the employment of an elderly lady, travelling with her employer to Southampton. In the panic and confusion of the collision she had been unable to save her employer. She joined the terrified crush of passengers lowered into the first lifeboat. When it capsized under the sheer weight of numbers, Anna ended up in the ocean. All the others from her lifeboat clambered back onto the sinking ship. Anna was alone in the treacherous sea until the survivors in the second lifeboat spotted her foundering in the water and pulled her up to safety.

Repercussions

The SS Elbe incident resulted in a court case which took place in Rotterdam in November 1895. The court found that the steamship Crathie was alone at fault for the collision. Amazingly the captain was merely censured for leaving the disaster, a verdict that astounded the maritime world at the time. The blame was put squarely on the first mate, who had left his post at the bridge at the critical time to chat in the galley with other crew members, and therefore had failed in his job of operating the ship's warning lights. The captain, officers and sailors of the SS Elbe received no rebuke from the court either, which caused some concern amongst the German public. The crew of the fishing smack Wildflower each were given, by Kaiser Wilhelm II, a silver and gold watch bearing his monogram and £5 as a gesture of thanks for saving the lives of the eighteen German citizens, an Austrian, and the English pilot. They also received other medals and gifts in the following years.

List of rescued passengers and crew members

Passenger Anna Boecker from Bremen

Passenger Carl A. Hofmann from Grand Island

Passenger Eugen Schlegel from Fuerth

Passenger Jan Vevera from Bohemia

Steerage passenger Wientje Bothen from Klinge

English pilot William Greenham from the Isle of Wight

Weser pilot H. A. de Harde from Lehe

Third officer Theodor Stollberg from Oldenburg

Chief engineer Albert Neussel from Bremerhaven

Purser Wilhelm Weser from Bremerhaven

Assistant purser Paul Schlutius from Berlin

Assistant engineer Ernst Linkmeyer from Hamburg

Assistant engineer Friedrich Sittig from Witten

Chief fireman Hermann Fuerst from Lehe

Seaman Gustav Wennig from Berlin

Seaman Paul Siebert from Jasenitz

Seaman Carl Finger from Geestemuende

Ordinary seaman William Dresow from Stemnitz

Ordinary seaman Anton Battke from Mechilinken

Steward Emil Kobe from Bremen

Wreck identified in 1987

In the early part of 1987 a group of Dutch amateur divers searched and located the wreck of the Elbe on the sea bed. They managed to salvage a small quantity of the glasswork and a quantity of porcelain as well as earthenware from the wreck site, which enabled them to identify the wreck.

References

- Description and Composition of the ship

- "A description of the ship and incident by Jan Lettens 06/08/2007". Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- Ship's description

- Description of the disaster from Suffolk County Council

- New York Times report 1 May 1895

- Miss Boecker's evidence, New York Times, 27 February 1895