Saṃkarṣaṇa

Saṃkarṣaṇa (IAST Saṃkarṣaṇa, "The Plougher")[7] later known as Balarama, was a son of Vasudeva Anakadundubhi, king of the Vrishnis in the region of Mathura.[8] He was a leading member of the Vrishni heroes, and may well have been an ancient historical ruler in the region of Mathura.[8][9][10][11] The cult of Saṃkarṣaṇa with that of Vāsudeva is historically one of the earliest forms of personal deity worship in India, attested from around the 4th century BCE.[12][13][14]

| Saṃkarṣaṇa | |

|---|---|

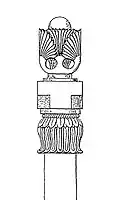

Saṃkarṣaṇa on a coin of Agathocles of Bactria, circa 190-180 BCE.[1][2] This is "the earliest unambiguous image" of the deity.[3][4] | |

| Affiliation | Balarama, Vishnu[5] |

| Personal information | |

| Born | |

| Parents | Devaki (mother) Vasudeva Anakadundubhi (father) |

| Siblings | Vāsudeva (youger brother) Subhadra (sister) |

| Vrishni heroes |

|---|

|

The cult of Vāsudeva and Saṃkarṣaṇa was one of the major independent cults, together with the cults of Narayana, Shri and Lakshmi, which later coalesced to form Vishnuism.[1] According to the Vaishnavite doctrine of the avatars, Vishnu takes various forms to rescue the world, and Vāsudeva as well as Saṃkarṣaṇa became understood as some of these forms, and some of the most popular ones.[15] This process lasted from the 4th century BCE when Vāsudeva and Saṃkarṣaṇa were independent deities, to the 4th century CE, when Vishnu became much more prominent as the central deity of an integrated Vaishnavite cult, with Vāsudeva and Saṃkarṣaṇa now only some of his manifestations.[15]

In epic and Puranic lore Saṃkarṣaṇa was also known by the names of Rama, Baladeva, Balarama, Rauhineya or Halayudha, and is presented as the elder brother of Vāsudeva.[16]

Initially, Saṃkarṣaṇa seems to hold precedence over his younger brother Vāsudeva, as he appears on the obverse on the coinage of king Agathocles of Bactria (circa 190-180 BCE), and usually first in the naming order as in the Ghosundi inscription.[17] Later this order was reversed, and Vāsudeva became the most important deity of the two.[17]

Characteristics

Evolution as a deity

The cult of Vāsudeva and Saṃkarṣaṇa may have evolved from the worship of a historical figure belonging to the Vrishni clan in the region of Mathura.[1] They are leading members of the five "Vrishni heroes".[1]

It is thought that the hero deity Saṃkarṣaṇa may have evolved into a Vaishnavite deity through a step-by-step process: 1) deification of the Vrishni heroes, of whom Vāduseva and Saṃkarṣaṇa were the leaders 2) association with the God Narayana-Vishnu 3) incorporation into the Vyuha concept of successive emanations of the God.[19] Epigraphically, the deified status of Saṃkarṣaṇa is confirmed by his appearance on the coinage of Agathocles of Bactria (190-180 BCE).[20] Later, the association of Saṃkarṣaṇa with Narayana (Vishnu) is confirmed by the Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions of the 1st century BCE.[20] By the 2nd century CE, the "avatara concept was in its infancy", and the depiction of the four emanations of Vishnu (the Chatur-vyūha), consisting in the Vrishni heroes including Vāsudeva, Saṃkarṣaṇa and minus Samba, starts to become visible in the art of Mathura at the end of the Kushan period.[21]

The Harivamsa describes intricate relationships between Krishna Vasudeva, Saṃkarṣaṇa, Pradyumna and Aniruddha that would later form a Vaishnava concept of primary quadrupled expansion, or chatur vyuha.[22]

The name of Samkarsana first appears in epigraphy in the Nanaghat cave inscriptions and the Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions, both dated to the 1st century BCE. In these inscriptions, Samkarsana appears before Vasudeva, suggesting seniority and precedence.

Saṃkarṣaṇa symbolism at Besnagar (circa 100 BCE)

Various sculptures and pillar capitals were found near the Heliodorus pillar in Besnagar, and it is thought they were dedicated to Vāsudeva's kinsmen, otherwise known as the Vrishni heroes and objects of the Bhagavata cult.[26] These are a tala (fan-palm capital), a makara(crocodile) capital, a banyan-tree capital, and a possible statue of the goddess Lakshmi, also associated with the Bhagavat cult.[27] Just as Garuda is associated with Vasudeva, the fan-palm capital is generally associated with Samkarsana, and the makara is associated with Pradyumna.[23][24] The banyan-tree capital with ashtanidhis is associated with Lakshmi.[27]

The presence of these pillar capitals, found near the Heliodorus pillar, suggests that the Bhagavata cult, although centered around the figures of Vāsudeva and Samkarsana, may also have involved the worship of other Vrishni deities.[24]

In his theriomorphic form, Saṃkarṣaṇa is associated to the lion.[28]

Parallels with Greek mythology

Saṃkarṣaṇa has been compared to the Greek god Dionysos, son of Zeus, as both are associated with the plough and with wine, as well as a liking for wrestling and gourmet food.[29][30] Arrian in his Indika, quoting Megasthenes, writes of Dyonisos in India:

About Dionysos he writes: "Dionysos, however, when he came and had conquered the people, founded cities and gave laws to these cities, and introduced the use of wine among Indians, as he had done among the Greeks, and taught them to sow the land, himself supplying seeds for the purpose (...) It is also said that Dionysos first yoked oxen to the plough, and made many of the Indians husbandmen instead of nomads, and furnished them with the implements of agriculture; and that the Indians worship the other gods, and Dionysos himself in particular, with cymbals and drums, because he so taught them; and he also taught them the satiric dance, or, as the Greeks call it, the Kordax and that he instructed the Indians to let their hair grow long in honor of the god, and to wear the turban"

— Arrian, Indika, Chapter VII.[31]

Bacchanalian orgies

Early on, the cult of Smarkasana is associated with the abuse of wine, and the Bacchanalian features of the cult of Dionysus are also found in the cult of Saṃkarṣaṇa.[32] The Mahabharata mentions the Bacchanalian orgies of Baladeva, another name of Smarkasana, and he is often depicted holding a cup in an inebriated state.[33]

Naneghat inscription (1st century BCE)

The Naneghat inscription, dated to the 1st century BCE, mentions both Samkarshana and Vāsudeva, along with the Vedic deities of Indra, Surya, Chandra, Yama, Varuna and Kubera.[34] This provided the link between Vedic tradition and the Vaishnava tradition.[35][36][37] Given it is inscribed in stone and dated to 1st-century BCE, it also linked the religious thought in the post-Vedic centuries in late 1st millennium BCE with those found in the unreliable highly variant texts such as the Puranas dated to later half of the 1st millennium CE. The inscription is a reliable historical record, providing a name and floruit to the Satavahana dynasty.[34][36][38]

Gosundi inscription

Vāsudeva and Saṃkarṣaṇa are also mentioned in the 1st century BCE Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions in association with Narayana:[1]

(This) enclosing wall round the stone (object) of worship, called Narayana-vatika (Compound) for the divinities Samkarshana-Vasudeva who are unconquered and are lords of all (has been caused to be made) by (the king) Sarvatata, a Gajayana and son of (a lady) of the Parasaragotra, who is a devotee of Bhagavat (Vishnu or Samkarshana/Vāsudeva) and has performed an Asvamedha sacrifice.

– Ghosundi Hathibada Inscriptions, 1st-century BCE[40]

Chilas petroglyphs

At Chilas II archeological site dated to the first half of 1st-century CE in northwest Pakistan, near the Afghanistan border, are engraved two males along with many Buddhist images nearby. The larger of the two males holds a plough and club in his two hands. The artwork also has an inscription with it in Kharosthi script, which has been deciphered by scholars as Rama-Krsna, and interpreted as an ancient depiction of the two brothers Saṃkarṣaṇa and Krishna.[41][42]

Saṃkarṣaṇa in Indo-Scythian coinage (1st century BCE)

Samkarshana, the Vrishni elder and the leading divinity until the rise to precedence of Vāsudeva, is known to appear on the coinage of the Indo-Scythian rulers Maues and Azes I during the 1st century BCE.[43][44] These coins show him holding a mace and a plough.[43][44][45]

Samkarsana-Balarama on a coin of Azes (58-12 BCE)

Samkarsana-Balarama on a coin of Azes (58-12 BCE)

Saṃkarṣaṇa in 2nd century CE sculpture

Some sculptures during this period suggest that the concept of the avatars was starting to emerge, as images of "Chatur-vyuha" (the four emanations of Narayana) are appearing.[46] The famous "Caturvyūha" statue in Mathura Museum is an attempt to show in one composition Vāsudeva together with the other members of the Vrishni clan of the Pancharatra system: Saṃkarṣaṇa, Pradyumna and Aniruddha, with Samba missing, Vāsudeva being the central deity from whom the others emanate.[10] The back of the relief is carved with the branches of a Kadamba tree, symbolically showing the relationship being the different deities.[10] The depiction of Vishnu was stylistically derived from the type of the ornate Bodhisattvas, with rich jewelry and ornate headdress.[47]

Saṃkarṣaṇa in the Kondamotu relief (4th century CE)

Saṃkarṣaṇa appears prominently in a relief from Kondamotu, Guntur district in Andhra Pradesh, dating to the 4th century CE, which shows the Vrishni heroes standing in genealogical order around Narasimha.[48][49] Saṃkarṣaṇa stands to the left in the place of seniority, holding a mace and a ploughshare topped by the depiction of a lion, followed by Vāsudeva, with a hand in abhaya mudra and the other hand on the hip holding a conch shell.[48] Vāsudeva also has a crown, which distinguishes him from the others.[50] Then follow Pradyumna, holding a bow and an arrow, Samba, holding a wine goblet, and Aniruddha, holding a sword and a shield.[48] The fact that they stand around Narasimha suggests a fusion of the Satvata cult with the Vrishni cult.[48]

Lion symbol

%252C_Gupta_period%252C_mid-5th_century_AD._Boston_Museum.jpg.webp)

In Vaishnavism, Saṃkarṣaṇa is associated with the lion, which is his theriomorphic aspect.[53][51] He can be identified as Narasimha.[54][55] Saṃkarṣaṇa appears as a lion in some of the Caturvyūha statues (the Bhita statue), where he is an assistant to Vāsudeva, and in the Vaikuntha Chaturmurti when his lion's head protrudes from the side of Vishnu's head.[51]

Saṃkarṣaṇa is also associated with the quality of knowledge.[55]

See also

Footnotes

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 436–438. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- Osmund Bopearachchi, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence, 2016.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL. p. 215. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- Austin, Christopher R. (2019). Pradyumna: Lover, Magician, and Scion of the Avatara. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-005412-0.

- Bryant 2007, p. 114.

- Raychaudhuri 1972, p. 124

- "Sanskritdictionary.com: Definition of saṃkarṣaṇa". www.sanskritdictionary.com.

- Vāsudeva and Krishna "may well have been kings of this dynasty as well" in Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press. p. 151–152 and Fig.51.

- Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. p. 129. ISBN 978-90-04-06498-0.

- Paul, Pran Gopal; Paul, Debjani (1989). "Brahmanical Imagery in the Kuṣāṇa Art of Mathurā: Tradition and Innovations". East and West. 39 (1/4): 132–136, for the photograph p.138. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756891.

- Smagur, Emilia. "Vaishnavite Influences in the Kushan Coinage, Notae Numismaticae- Zapiski Numizmatyczne, X (2015)": 67. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Doris Srinivasan (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL Academic. pp. 211–220, 236. ISBN 90-04-10758-4.

- Gavin D. Flood (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- Christopher Austin (2018). Diana Dimitrova and Tatiana Oranskaia (ed.). Divinizing in South Asian Traditions. Taylor & Francis. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-1-351-12360-0.

- Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (2016). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4.

- Austin, Christopher R. (2019). Pradyumna: Lover, Magician, and Scion of the Avatara. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-005412-0.

- Austin, Christopher R. (2019). Pradyumna: Lover, Magician, and Scion of the Avatara. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-005412-0.

- Gupta, Vinay K. "Vrishnis in Ancient Literature and Art". Indology's Pulse Arts in Context, Doris Meth Srinivasan Festschrift Volume, Eds. Corinna Wessels Mevissen and Gerd Mevissen with Assistance of Vinay Kumar Gupta: 70–72.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1979). "Early Vaiṣṇava Imagery: Caturvyūha and Variant Forms". Archives of Asian Art. 32: 50. JSTOR 20111096.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1979). "Early Vaiṣṇava Imagery: Caturvyūha and Variant Forms". Archives of Asian Art. 32: 51. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111096.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 439. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- "Chatur vyuha," article at Bhaktipedia (a Hare Krishna's site).

- Gupta, Vinay K. "Vrishnis in Ancient Literature and Art". Indology's Pulse Arts in Context, Doris Meth Srinivasan Festschrift Volume, Eds. Corinna Wessels Mevissen and Gerd Mevissen with Assistance of Vinay Kumar Gupta: 81.

- Austin, Christopher R. (2019). Pradyumna: Lover, Magician, and Scion of the Avatara. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-005412-0.

- Shaw, Julia (2016). Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, c. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD. Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-315-43263-2.

- Indian History. Allied Publishers. 1988. p. A-222. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4.

- Indian History. Allied Publishers. 1988. p. A-224. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1979). "Early Vaiṣṇava Imagery: Caturvyūha and Variant Forms". Archives of Asian Art. 32: 39–40. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111096.

- "We find Dionysos to be the same as Samkarsana because just as in Greece the former is associated with wine and plough so is the latter in India" Bose, Ananta Kumar (1934). Indian Historical Quarterly Vol.10. p. 288.

- "The cult of Dionysus with its Bacchanalian features reminds us of the cult of Samkarsana." Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta (1952). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas. Bharatiya Itihas Parishad. p. 306.

- Puskás, Ildikó (1990). "Magasthenes and the "Indian Gods" Herakles and Dionysos". Mediterranean Studies. 2: 42. ISSN 1074-164X. JSTOR 41163978.

- "The cult of Dionysus with its Bacchanalian features reminds us of the cult of Samkarsana." Sastri, K. a Nilakanta (1952). Age Of The Nandas And Mauryas. p. 306.

- "...the inebriate condition of this Avatara which is fully corroborated by the presence of the wine cup in the hands of some of the extant images of Balarama, as well as the goggle eyes depicted in others. The 'Mahabharata' refers to the bacchanalian orgies of Baladeva" in Journal of the Indian society of oriental art vol.14. 1946. p. 29.

- Charles Allen 2017, pp. 169-170.

- Joanna Gottfried Williams (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL Academic. pp. 129–130. ISBN 90-04-06498-2.

- Mirashi 1981, pp. 131-134.

- Edwin F. Bryant (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 18 note 19. ISBN 978-0-19-972431-4.

- Vincent Lefèvre (2011). Portraiture in Early India: Between Transience and Eternity. BRILL Academic. pp. 33, 85–86. ISBN 978-9004207356.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL. p. 215. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- D. R. Bhandarkar, Hathi-bada Brahmi Inscription at Nagari, Epigraphia Indica Vol. XXII, Archaeological Survey of India, pages 198-205

- Doris Srinivasan (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL Academic. pp. 214–215 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-10758-4.

- Jason Neelis (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. BRILL Academic. pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL. p. 215. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- Srinivasan, Doris (2007). On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World. BRILL. p. 22. ISBN 978-90-474-2049-1.

- Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. p. 80 with image and description of the same coin type: "Indian God Balarama walking to left, holding club and plough". ISBN 978-0-9518399-1-1.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 439. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- Bautze-Picron, Claudine (2013). "A neglected Aspect of the Iconography of Viṣṇu and other Gods and Goddesses". Journal of the Indian Society of Oriental Arts. XXVIII–XXIX: 81–92.

- Gupta, Vinay K. "Vrishnis in Ancient Literature and Art". Indology's Pulse Arts in Context, Doris Meth Srinivasan Festschrift Volume, Eds. Corinna Wessels Mevissen and Gerd Mevissen with Assistance of Vinay Kumar Gupta: 74–75.

- Austin, Christopher R. (2019). Pradyumna: Lover, Magician, and Son of the Avatara. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-005411-3.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL. p. 217. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1979). "Early Vaiṣṇava Imagery: Caturvyūha and Variant Forms". Archives of Asian Art. 32: 39–54. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111096.

- For English summary, see page 80 Schmid, Charlotte (1997). "Les Vaikuṇṭha gupta de Mathura : Viṣṇu ou Kṛṣṇa?" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 52: 60–88. doi:10.3406/arasi.1997.1401.

- "Samkarsana is represented by his theriomorphic form, the lion..." in Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL. p. 253–254. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL. p. 241 Note 9. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- "Gentleness and strength are associated with Vasudeva, "knowledge with Samkarsana, (Narasimha) female power with Pradyumna (Varaha) and ferociousness and sovereignty with Aniruddha (Kapila)." Kamalakar, G.; Veerender, M. (1993). Vishnu in Art, Thought & Literature. Birla Archeological & Cultural Research Institute. p. 92.

References

- Charles Allen (2017), "6", Coromandel: A Personal History of South India, Little Brown, ISBN 978-1408705391

- Mirashi, Vasudev Vishnu (1981), History and Inscriptions of the Satavahanas: The Western Kshatrapas, Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture

- Fortson, Benjamin W., IV (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-0316-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hastings, James Rodney (2003) [1908–26]. Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. 4. John A Selbie (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 476. ISBN 0-7661-3673-6. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

The encyclopedia will contain articles on all the religions of the world and on all the great systems of ethics. It will aim at containing articles on every religious belief or custom, and on every ethical movement, every philosophical idea, every moral practice.

- Hein, Norvin (1986). "A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: The Cult of Gopāla: History of Religions, Vol. 25, No. 4 (May, 1986), pp. 296-317". History of Religions. 25 (4): 296–317. doi:10.1086/463051. JSTOR 1062622.

- SINGER, Milton (1900). Krishna Myths Rites & Attitudes. UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO. ISBN 0-313-22822-1.

- Delmonico, N. (2004). "The History Of Indic Monotheism And Modern Chaitanya Vaishnavism". The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12256-6. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- Mahony, W.K. (1987). "Perspectives on Krsna's Various Personalities". History of Religions. 26 (3): 333–335. doi:10.1086/463085. JSTOR 198702.

- BHATTACHARYA, Gouriswar: Vanamala of Vasudeva-Krsna-Visnu and Sankarsana-Balarama. In: Vanamala. Festschrift A.J. Gail. Serta Adalberto Joanni Gail LXV. diem natalem celebranti ab amicis collegis discipulis dedicata. Gerd J.R. Mevissen et Klaus Bruhn redigerunt. Berlin 2006; pp. 9–20.

- COUTURE, André: The emergence of a group of four characters (Vasudeva, Samkarsana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha) in the Harivamsa: points for consideration. Journal of Indian Philosophy 34,6 (2006) 571-585.