Salus

Salus (Latin: salus, "safety", "salvation", "welfare")[1] was a Roman goddess. She was the goddess of safety and well-being (welfare, health and prosperity) of both the individual and the state. She is sometimes equated with the Greek goddess Hygieia, though her functions differ considerably.

Salus is one of the most ancient Roman Goddesses: she is also recorded once as Salus Semonia,[2] a fact that might hint to her belonging to the category of the Semones, such as god Semo Sancus Dius Fidius. This view though is disputes among scholars. The issue is discussed in the section below. The two gods had temples in Rome on the Collis Salutaris and Mucialis respectively,[3] two adjacent hilltops of the Quirinal, located in the regio known as Alta Semita. Her temple, as Salus Publica Populi Romani, was voted in 304 BC, during the Samnite Wars, by dictator Gaius Junius Bubulcus Brutus,[4] dedicated on 5 August 302 and adorned with frescos at the order of Gaius Fabius Pictor.[5]

The high antiquity and importance of her cult is testified by the little-known ceremony of the Augurium Salutis, held every year on August 5 for the preservation of the Roman state.[6] Her cult was spread over all Italy.[7] Literary sources record relationships with Fortuna[8] and Spes.[9] She started to be increasingly associated to Valetudo, the Goddess of Personal Health, which was the real romanized name of Hygieia.

Later she become more a protector of personal health. Around 180 BCE sacrificial rites in honour of Apollo, Aesculapius, and Salus took place there (Livius XL, 37). There was a statue to Salus in the temple of Concordia. She is first known to be associated with the snake of Aesculapius from a coin of 55 BC minted by M. Acilius.[10] Her festival was celebrated on March 30.

Salus and Sancus

The two deities were related in several ways. Their shrines (aedes) were very close to each other on two adjacent hilltops of the Quirinal, the Collis Mucialis and Salutaris respectively.[11] Some scholars also claim some inscriptions to Sancus have been found on the Collis Salutaris.[12] Moreover, Salus is the first in the series of deities mentioned by Macrobius as related in their sacrality: Salus, Semonia, Seia, Segetia, Tutilina,[13] who required the observance of a dies feriatus of the person who happened to utter their name. These deities were connected to the ancient agrarian cults of the valley of the Circus Maximus that remain mysterious.[14]

German scholars Georg Wissowa, Eduard Norden and Kurt Latte write of a deity named Salus Semonia,[15] who is attested to only in one inscription of year 1 A.D., mentioning a Salus Semonia in its last line (line seventeen). There is consensus among scholars that this line is a later addition and cannot be dated with certainty.[16] In other inscriptions, Salus is never connected to Semonia.[17]

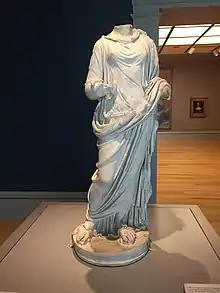

Representation

Salus was often shown seated with her legs crossed (a common position for Securitas), leaning her elbow on the arm of her throne. Often, her right hand holds out a patera (shallow dish used in religious ceremonies) to feed a snake which is coiled round an altar. The snake is reared up and dips its head to the patera.

Sometimes her hand is open and empty, making a gesture. Sometimes the snake directs its gaze along with hers. Sometimes there is no altar; the snake is coiled around the arm of her throne instead.

Occasionally, Salus has a tall staff in her left hand with a snake twined around it; sometimes her right hand raises a smaller female figure. Later, Salus is shown standing, feeding her snake. This became the commonest pose: she is standing and grasping the wriggling snake firmly under her arm, directing it to the food she holds out on a dish in her other hand. Rarely, Salus is holding a steering oar in her left hand (indicates her role in guiding the emperor through a healthy life). This really belongs to Fortuna.

A poem to the Goddess Salus in the African desert

On the construction of the fort of Bu Njem in the African desert (AD 202), centurion Avidius Quintianus dedicated a poem to Goddess Salus in the baths; probably the poem was added directly after the baths were finished. The baths were consecrated to Salus, and we should ask why the centurion chose Goddess Salus to put the baths under her sanction. The Goddess is well adapted to the ordinary life on the site. Moreover, Salus granted not only health but also safety. The choice of Salus could also attract sympathy to the troops at Bu Njem which also would extend to the absent troops. The poem refers to the benefits of Salus such as Salutis lymphas and Salutis gratia. These were not only the waves belonging to Salus but also the benefits of the water and the care for health.

In fact the feeling which dominates the poem is “Solicitude and Friendship”, Solicitude not only towards his home remainders in the camp, but also towards who will succeed him, and friendship towards the fraction of the garrison which departed in operation. The poem runs as follows:

- Q Avidius Quintianus- centurio leg(ionis) III Aug(ustae)

- Faciendum curavit

- Quaesii multum quot memoriae tradere

- A gens prae cunctos in hac castra milites

- Votum communem proque reditu exercitus

- Inter priores et futuros reddere

- Dum quaero mecum digna nomina

- Inveni tandem nomen et numen deae

- Votis perennem quem dicare in hoc loco

- Salutis igitur quandium cultures sient

- Qua potui sanxi nomen et cunctis dedi

- Veras saltis lymphas tantis ignibus

- In istis simper harenacis collibus

- Nutantis austri solis flammas fervidas

- Tranquille ut nando delenirent corpora

- Ita tu qui sentis magnam facti gratiam

- Aestuantis animae fucilari spiritum

- Noli pigere laudem voce reddere

- Veram qui voluit esse sanum tibi

- Set protestare vel salutis gratia

Bibliography

- W. Köhler in Enciclopedia dell' Arte Antica Roma Istituto Treccani 1965 (online) s.v.

- The Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania (IRT), eds. J.M. Reynolds and Ward Perkins, Rome & London 1952, nos 918-919.

- René Rebuffat: "Les Centurions du Gholaia", Africa Romana II (1984), pp 233– 238.

- René Rebuffat: "Le poème de Q.Avidius Quintianus à la Déesse Salus", Karthago XXI, 1986-7, pp 95– 105.

- Omran (Ragab Salaam): The Limes Numidiae et Tripolitanus Under the Emperor Septimius Severus AD193-211, Unpublished PhD dissertation, Vienna University- Austria 2003, pp 76–79.

- Adams(J.N.) and Iasucthan (M. Porcius): "The Poets of Bu Njem: Language, Culture and the Centurionate", The Journal of Roman Studies (JRS), Vol. 89 (1999), pp. 109–134.

See also

- Hygieia, the Greek goddess of health

- Salus populi suprema lex esto

- Sirona, a goddess of health worshiped in East Central Gaul

References

- M. De Vaan Etymological Dictionary of Latin Leyden 2010 s.v.; The Oxford Classical Dictionary 4th ed. London & New York 2012 s.v.

- Köhler 1965, citing CIL VI 30975.

- Varro De Lingua latina V 53.

- Köhler 1965, citing Livy Ab Urbe Condita IX 43.

- Köhler 1965, citing Valerius Maximum VIII 14, 6.

- Köhler 1965, citing Tacit Annales XII 23.

- Köhler 1965 citing inscriptions from Orte (salutes pocolom Diehl Alt lat. Inschrit. 3, 192) and Pompei (salutei sacrum Dessau 3822).

- Köhler 1965, who cites Plautus Asin. 712.

- Köhler 1965, who cites Plautus Merc. 867.

- Köhler 1965.

- Varro Lingua Latina V 53.

- Jesse B. Carter in Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics vol. 13 s.v. Salus.

- Macrobius Saturnalia I 16,8

- G. Dumezil ARR Paris 1974, I. Chirassi Colombo in ANRW 1981 p.405; Tertullian De Spectculis VIII 3.

- G. Wissowa Roschers Lexicon s.v. Sancus, Religion und Kultus der Roemer Munich 1912 p. 139 ff.; E. Norden Aus der altrömischen Priesterbüchern Lund 1939 p. 205 ff.; K. Latte Rom. Religionsgeschichte Munich 1960 p. 49-51.

- Salus Semonia posuit populi Victoria; cf. R. E. A.Palmer: "Studies of the Northern Campus Martius in Ancient Rome" Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 1990 80.2. p. 19 and n.21 citing M. A. Cavallaro "Un liberto 'prega' per Augusto e per le gentes: CIL VI 30975 (con inediti di Th. Mommsen)" in Helikon 15-16 (1975-1976) pp 146-186.

- Ara Salutus from a slab of an altar from Praeneste; Salutes pocolom on a pitcher from Horta; Salus Ma[gn]a on a cippus from Bagnacavallo; Salus on a cippus from the sacred grove of Pisaurum; Salus Publica from Ferentinum; salutei sacrum from Pompei.