Saturn C-3

The Saturn C-3 was the third rocket in the Saturn C series studied from 1959 to 1962. The design was for a three-stage launch vehicle that could launch 45,000 kilograms (99,000 lb) to low Earth orbit and send 18,000 kilograms (40,000 lb) to the Moon via trans-lunar injection.[2][1]

Proposed Saturn C-3 and Apollo configuration (1962) | |

| Function | LEO and Lunar launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Boeing (S-IB-2) North American (S-II-C3) Douglas (S-IV) |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Cost per launch | 43.5 million |

| Cost per year | 1985 |

| Size | |

| Height | 269.0 feet (82.0 m) |

| Diameter | 320 inches (8.1 m) |

| Mass | 1,023,670 pounds (464,330 kg) |

| Stages | 3 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | |

| Mass | 100,000 pounds (45,000 kg) |

| Payload to GTO | |

| Mass | 50,000 pounds (23,000 kg) |

| Payload to TLI | |

| Mass | 39,000 pounds (18,000 kg)[1] |

| Associated rockets | |

| Family | Saturn |

| Derivatives | Saturn INT-20, Saturn INT-21 |

| Comparable | |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Proposed (1961) |

| Launch sites | Kennedy Space Center, SLC 37 (planned) |

| First stage – S-IB-2 | |

| Length | 113.10 feet (34.47 m) |

| Diameter | 320 inches (8.1 m) |

| Empty mass | 149,945 pounds (68,014 kg) |

| Gross mass | 1,599,433 pounds (725,491 kg) |

| Engines | 2 Rocketdyne F-1 |

| Thrust | 3,000,000 pounds-force (13,000 kN) |

| Specific impulse | 265 sec (sea level) |

| Burn time | 139 seconds |

| Fuel | RP-1/LOX |

| Second stage – S-II-C3 | |

| Length | 69.80 feet (21.28 m) |

| Diameter | 320 inches (8.1 m) |

| Empty mass | 54,978 pounds (24,938 kg) |

| Gross mass | 449,840 pounds (204,040 kg) |

| Engines | 4 Rocketdyne J-2 |

| Thrust | 800,000 pounds-force (3,600 kN) |

| Specific impulse | 300 sec (sea level) |

| Burn time | 200 seconds |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOX |

| Third stage – S-IV | |

| Length | 61.6 feet (18.8 m) |

| Diameter | 220 inches (5.6 m) |

| Empty mass | 11,501 pounds (5,217 kg) |

| Gross mass | 111,500 pounds (50,600 kg) |

| Engines | 6 Rocketdyne RL-10 |

| Thrust | 90,000 pounds-force (400 kN) |

| Specific impulse | 410 sec |

| Burn time | 482 seconds |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOX |

U.S. President Kennedy's proposal on May 25, 1961, of an explicit crewed lunar landing goal spurred NASA to solidify its launch vehicle requirements for a lunar landing. A week earlier, William Fleming (Office of Space Flight Programs, NASA Headquarters) chaired an ad hoc committee to conduct a six-week study of the requirements for a lunar landing. Judging the direct ascent approach to be the most feasible, they concentrated their attention accordingly, and proposed circumlunar flights in late 1965 using the Saturn C-3 launch vehicle.

In early June 1961, Bruce Lundin, deputy director of the Lewis Research Center, led a week-long study of six different rendezvous possibilities. The alternatives included Earth-orbital rendezvous (EOR), lunar-orbital rendezvous (LOR), Earth and lunar rendezvous, and rendezvous on the lunar surface, employing Saturn C-1s, C-3s, and Nova designs. Lundin's committee concluded that rendezvous enjoyed distinct advantages over direct ascent and recommended an Earth-orbital rendezvous using two or three Saturn C-3s.[3]

NASA announced on September 7, 1961, that the government-owned Michoud Ordnance Plant near New Orleans, Louisiana, would be the site for fabrication and assembly of the Saturn C-3 first stage as well as larger vehicles in the Saturn program. Finalists were two government-owned plants in St. Louis and New Orleans. The height of the factory roof at Michoud meant that a launch vehicle with eight F-1 engines (Nova class, Saturn C-8) could not be built; four or five engines (first stage) would have to be the maximum (Saturn C-5)

This decision ended consideration of a Nova class launch vehicle for a direct ascent to the Moon or as a heavy-lift companion with the Saturn C-3 for Earth orbit rendezvous.

Lunar mission design

Direct Ascent

During various Nova's proposal, a Modular Nova concept made up of clustering the first stage of C-3 were proposed.[4]

Earth orbit rendezvous

The Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama developed an Earth orbit rendezvous proposal (EOR) for the Apollo program in 1960-1961. The proposal used a series of small rockets half the size of a Saturn V to launch different components of a spacecraft headed to the Moon. These components would be assembled in orbit around the Earth, then sent to the Moon via trans-lunar injection. In order to test and validate the feasibility of the EOR approach for the Apollo program, Project Gemini was founded with this objective: "To effect rendezvous and docking with another vehicle (Agena target vehicle), and to maneuver the combined spacecraft using the propulsion system of the target vehicle".

The Saturn C-3 was the primary launch vehicle for Earth orbit rendezvous. The booster consisted of a first stage containing two Saturn V F-1 engines, a second stage containing four powerful J-2 engines, and the S-IV stage from a Saturn I booster. Only the S-IV stage of the Saturn C-3 was developed and flown, but all of the specified engines were used on the Saturn V rocket which took men to the Moon.[5]

Lunar orbit rendezvous

The concept of Lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) was studied at Langley Research Center as early as 1960. John Houbolt's memorandum advocating LOR for lunar missions in November 1961 to Robert Seamans outlined the usage of the Saturn C-3 launch vehicle, and avoiding complex large boosters and lunar landers.[6]

After six months of further discussion at NASA, in the summer of 1962, Langley Research Center‘s Lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) proposal was officially selected as the mission configuration for the Apollo program on November 7, 1962.[7] By the end of 1962, the Saturn C-3 design was deemed not necessary for Apollo program requirements as larger boosters (Saturn C-4, Saturn C-5) were then proposed, hence further work on the Saturn C-3 was cancelled.[8]

Variants and derivatives

Since 1961, a number of variants of the Saturn C-3 have been studied, proposed, and funded. The most extensive studies focused on the Saturn C-3B variants before the end of 1962, when lunar orbit rendezvous was selected and Saturn C-5 development approved. The common theme of these variants is the first stage with at least 3,044,000 lbf (13,540 kN) of sea-level thrust (SL). These designs used two or three Rocketdyne F-1 engines in a S-IB-2 or S-IC stage and diameters ranging from 8 to 10 meters (27 to 33 feet) that could lift up to 110,000 pounds (50,000 kg) to Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

The lack of a Saturn C-3 launch vehicle in 1965 created a large payload gap (LEO) between the Saturn IB's 21,000 kg (46,000 lb) capacity and the two-stage Saturn V's 75,000 kg (165,000 lb) capability. In the mid-1960s NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) initiated several studies for a launch vehicle to fill this payload capacity gap and to extend the capabilities of the Saturn family. Three companies provided proposals to MSFC for this requirement: Martin Marietta (builder of Atlas, Titan vehicles), Boeing (builder of S-1B and S-1C first stages), and North American (builder of the S-II second stage).

Saturn C-3B

The Saturn C-3B revision (1961) increased the total thrust of the three stages to 17,200 kN. The diameter of the first stage (S-IB-2) was increased to 33 feet (10 meters). The eventual first stage for the Saturn V (S-IC) would use this same diameter, but add 8 meters to its length. A further consideration added a third F-1 engine to the first stage. The S-II, second stage diameter would be 8.3 meters (326 inches) and 21.3 meters (70 feet) in length.

The 3-stage version would use the S-IV stage, with a diameter of 5.5 meters and 12.2 meters in length.

Saturn C-3BN

The Saturn C-3BN revision (1961) would use the NERVA for the third stage in this launch vehicle. The NERVA technology has been studied and proposed since mid-1950s for future space exploration.

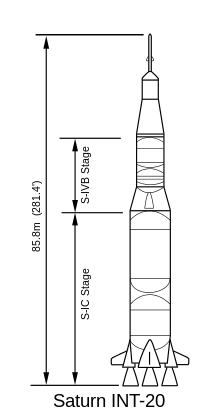

Saturn INT-20

On 7 October 1966, Boeing submitted a Final Report to the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, "Studies of Improved Saturn V Vehicles and Intermediate Payload Vehicles". That report outlined the Saturn INT-20, an intermediate two-stage launch vehicle with an S-1C first stage using three or four F-1 engines, and an S-IVB as the second stage with one J-2 engine. The vehicle's payload capacity for LEO would be 45,000 to 60,000 kg, comparable to the earlier Saturn C-3 design (1961). Boeing projected delivery and first flight in 1970, based on a decision by 1967.

Post-Apollo development

The need for a launch vehicle of Saturn C-3 capacity (45 tonnes to LEO) continued beyond the Apollo program. Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 37, initially designed to serve the Saturn I and I-B, was planned for eventual Saturn C-3 usage, but it was deactivated in 1972. In 2001, Boeing refurbished the complex for its Delta IV EELV launch vehicle. The Delta IV Heavy variant can only launch 22.5 tonnes to LEO.

The 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster and 2010 Space Launch System program resulted in renewed proposals for Saturn C-3 derivatives using the Rocketdyne F-1A engines with existing booster cores and tooling (10m - Saturn S-IC stage; 8.4m - Space Shuttle external tank; 5.1m - Delta IV Common Booster Core).

Jarvis

After the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, the United States Air Force (USAF) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) conducted a joint Advanced Launch System study (1987-1990). Hughes Aircraft and Boeing dusted off the earlier Saturn C-3 design and submitted their proposal for the Jarvis launch vehicle.

The Jarvis would be a three-stage rocket, 58 m (190 ft) in height and 8.38 m (27.5 ft) in diameter. Designed to lift 38 tons to LEO, it would utilize F-1 and J-2 rocket engines and tooling in storage from the Saturn V rocket program along with more recent Shuttle-era technologies to provide lower launch costs.[9]

Pyrios

Pyrios is an advanced booster concept proposed in 2012 by Dynetics for use on NASA's Space Launch System heavy-lift launch vehicle. Pyrios was intended to use the RP-1/LOX F-1B, a modernized version of the F-1A engine built by Aerojet Rocketdyne. Developed during the later stages of the Apollo program, the F-1A was test-fired but never flew. Several were created and stored by Rocketdyne. The company has also maintained an F-1/F-1A knowledge retention program for its engineers for the entire period the engine has been mothballed. Dynetics is now performing tests on engine components pulled from storage. Pyrios was intended to use the same attachment points as the five-segment SRBs[10]

The Dynetics booster would attach at these points and apply thrust to an upper thrust beam in the SLS core, rather than at the bottom. Like Saturn C-3 first stage, the proposed Dynetics booster would employ two F-1(A) heritage engines.[11][12]

The manager of NASA's SLS advanced development office indicated that the Pyrios proposal was viable.[13]

The planned 2015 competition in support of SLS Block 1A, was cancelled after studies and testing determined that the advanced booster would have resulted in unsuitably high acceleration and poor abort scenarios (manned crew).[14] Based on the conclusions of this study, NASA cancelled the SLS Block 1A configuration.[15]

The need for Advanced Booster with SLS Block 2 is not expected until late 2020s.

References

Inline citations

- Young, Anthony. The Saturn V F-1 Engine: Powering Apollo into History. pp. 21–23.

- "Saturn C-3". Astronautix.com. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Benson, Charles D.; William Barnaby Faherty (1978). "4-8". Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. NASA (SP-4204). Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- https://history.nasa.gov/MHR-5/part-2.htm

- Bilsten, Roger E. (1980). Stages to Saturn. NASA SP-4206. pp. 48–63.

- Bilsten, Roger E. (1980). Stages to Saturn. NASA SP-4206. p. 63.

- "The Rendezvous That Was Almost Missed: Lunar Orbit Rendezvous and the Apollo Program". NASA Langley Research Center. December 1992. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- David M. Reeves; Michael D. Scher; Alan W. Wilhite; Douglas O. Stanley (2005). "The Apollo Lunar Orbit Rendezvous Architecture Decision Revisited" (PDF). National Institute of Aerospace, Georgia Tech. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- "Jarvis launch vehicle". Astronautix.com. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Stephen Clark (18 April 2012). "Rocket companies hope to repurpose Saturn 5 engines". Spaceflight Now.

- Chris Bergin (9 November 2012). "Dynetics and PWR aiming to liquidize SLS booster competition with F-1 power". Spaceflight.com.

- Lee Hutchinson (14 April 2013). "New F-1B rocket engine upgrades Apollo-era design with 1.8M lbs of thrust". ars technica.

- "SLS Block II drives hydrocarbon engine research". thespacereview.com. January 14, 2013.

- "Wind Tunnel testing conducted on SLS configurations, including Block 1B". NASASpaceFlight.com.

- Bergin, Chris. "Advanced Boosters progress towards a solid future for SLS". NasaSpaceFlight.com. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

Bibliography

- Bilstein, Roger E, Stages to Saturn, US Government Printing Office, 1980. ISBN 0-16-048909-1. An excellent account of the evolution, design, and development of the Saturn launch vehicles.

- Stuhlinger, Ernst, et al., Astronautical Engineering and Science: From Peenemuende to Planetary Space, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964.

- Jet Propulsion Lab; NASA Report - October 2, 1961; Some Interrelationships and Long-Range Implications of C-3 Lunar Rendezvous and solid Nova vehicle concepts. Accessed at: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19740072519_1974072519.pdf.

- Robert P. Smith, Apollo Projects Office, NASA Report, Project Apollo - A description of a Saturn C-3 and Nova vehicle. July 25, 1961. Accessed at: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19790076768_1979076768.pdf.

- NASA, "Earth Orbital Rendezvous for an Early Manned Lunar Landing," pt. I, "Summary Report of Ad Hoc Task Group Study" [Heaton Report], August 1961.

- David S. Akens, Saturn Illustrated Chronology: Saturn's First Eleven Years, April 1957 through April 1968, 5th ed., MHR-5 (Huntsville, Alabama: MSFC, 20 Jan. 1971).

- Boeing Study, Marshall Space Flight Center, '"Final Report - Studies of Improved Saturn V Vehicles and Intermediate Payload Vehicles'", October 7, 1966, Accessed at: http://www.astronautix.com/data/satvint.pdf

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.