Scalping

Scalping is the act of cutting or tearing a part of the human scalp, with hair attached, from the head, and generally occurred in warfare with the scalp being a trophy.[1] Scalp-taking is considered part of the broader cultural practice of the taking and display of human body parts as trophies, and may have developed as an alternative to the taking of human heads, for scalps were easier to take, transport, and preserve for subsequent display. Scalping independently developed in various cultures in both the Old and New Worlds.[2]

Africa and Europe

In England in 1036, Earl Godwin, father of Harold Godwinson, was reportedly responsible for scalping his enemies. According to the ancient Abingdon manuscript, 'some of them were blinded, some maimed, some scalped. No more horrible deed was done in this country since the Danes came and made peace here'.[3]

Georg Frederici noted that “Herodotus provided the only clear and satisfactory portrayal of a scalping people in the old world” in his description of the Scythians, a nomadic people then located to the north and west of the Black Sea.[4] Herodotus related that Scythian warriors would behead the enemies they defeated in battle and present the heads to their king to claim their share of the plunder. Then, the warrior would skin the head “by making a circular cut round the ears and shaking out the skull; he then scrapes the flesh off the skin with the rib of an ox, and when it is clean works it with his fingers until it is supple, and fit to be used as a sort of handkerchief. He hangs these handkerchiefs on the bridle of his horse, and is very proud of them. The best man is the man who has the greatest number.”[5]

Ammianus Marcellinus noted the taking of scalps by the Alani, a people of Asiatic Scythia, in terms quite similar to those used by Herodotus.[6]

The Abbé Emmanuel H. D. Domenech referenced the decalvare of the ancient Germans and the capillos et cutem detrahere of the code of the Visigoths as examples of scalping in early medieval Europe,[7] though some more recent interpretations of these terms relate them to shaving off the hair of the head as a legal punishment rather than scalping.[8]

In 1845, mercenary John Duncan observed what he estimated to be 700 scalps taken in warfare and displayed as trophies by a contingent of female soldiers—Dahomey Amazons—employed by the King of Dahomey (present-day Republic of Benin). Duncan noted that these would have been taken and kept over a long period of time and would not have come from a single battle. Although Duncan travelled widely in Dahomey, and described customs such as the taking of heads and the retention of skulls as trophies, nowhere else does he mention scalping.[9][10]

Americas

Techniques

Specific scalping techniques varied somewhat from place to place, depending on the cultural patterns of the scalper regarding the desired shape, size, and intended use of the severed scalp, and on how the victims wore their hair, but the general process of scalping was quite uniform. The scalper firmly grasped the hair of a subdued adversary, made several quick semicircular cuts with a sharp instrument on either side of the area to be taken, and then vigorously yanked at the nearly-severed scalp. The scalp separated from the skull along the plane of the areolar connective tissue, the fourth (and least substantial) of the five layers of the human scalp. Scalping was not in itself fatal, though it was most commonly inflicted on the gravely wounded or the dead. The earliest instruments used in scalping were stone knives crafted of flint, chert, or obsidian, or other materials like reeds or oyster shells that could be worked to carry an edge equal to the task. Collectively, such tools were also used for a variety of everyday tasks like skinning and processing game, but were replaced by metal knives acquired in trade through European contact. The implement, often referred to as a “scalping knife” in popular American and European literature, was not known as such by Native Americans, a knife being for them just a simple and effective multi-purpose utility tool for which scalping was but one of many uses.[11][12]

Intertribal warfare

Author and historian Mark van de Logt wrote, "Although military historians tend to reserve the concept of 'total war'", in which civilians are targeted, "for conflicts between modern industrial nations," the term "closely approaches the state of affairs between the Pawnees, the Sioux, and the Cheyennes. Noncombatants were legitimate targets. Indeed, the taking of a scalp of a woman or child was considered honorable because it signified that the scalp taker had dared to enter the very heart of the enemy's territory."[13]

Many tribes of Native Americans practiced scalping, in some instances up until the end of the 19th century. Of the approximately 500 bodies at the Crow Creek massacre site, 90 percent of the skulls show evidence of scalping. The event took place circa 1325 AD.[14]

Colonial wars

The Connecticut and Massachusetts colonies offered bounties for the heads of killed hostile Indians, and later for just their scalps, during the Pequot War in the 1630s;[15] Connecticut specifically reimbursed Mohegans for slaying the Pequot in 1637.[16] Four years later, the Dutch in New Amsterdam offered bounties for the heads of Raritans.[16] In 1643, the Iroquois attacked a group of Huron pelters and French carpenters near Montreal, killing and scalping three of the French.[17]

Bounties for Indian captives or their scalps appeared in the legislation of the American colonies during the Susquehannock War (1675–77).[18] New England offered bounties to white settlers and Narragansett people in 1675 during King Philip's War.[16] By 1692, New France also paid their native allies for scalps of their enemies.[16] In 1697, on the northern frontier of Massachusetts colony, settler Hannah Duston killed ten of her Abenaki captors during her nighttime escape, presented their ten scalps to the Massachusetts General Assembly, and was rewarded with bounties for two men, two women, and six children, even though Massachusetts had rescinded the law authorizing scalp bounties six months earlier.[15] There were six colonial wars with New England and the Iroquois Confederacy fighting New France and the Wabanaki Confederacy over a 75-year period, starting with King William's War in 1688. All sides scalped victims, including noncombatants, during this frontier warfare.[19] Bounty policies originally intended only for Native American scalps were extended to enemy colonists.[16]

Massachusetts created a scalp bounty during King William's War in July 1689.[20] During Queen Anne's War, by 1703, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was offering $60 for each native scalp.[21] During Father Rale's War (1722–1725), on August 8, 1722, Massachusetts put a bounty on native families.[22] Ranger John Lovewell is known to have conducted scalp-hunting expeditions, the most famous being the Battle of Pequawket in New Hampshire.

In the 1710s and '20s, New France engaged in frontier warfare with the Natchez people and the Meskwaki people, during which both sides would employ the practice. In response to repeated massacres of British families by the French and their native allies during King George's War, Massachusetts governor William Shirley issued a bounty in 1746 to be paid to British-allied Indians for the scalps of French-allied Indian men, women, and children.[23] New York passed a Scalp Act in 1747.[24]

During Father Le Loutre's War and the Seven Years' War in Nova Scotia and Acadia, French colonists offered payments to Indians for British scalps.[25] In 1749, British Governor Edward Cornwallis created an extirpation proclamation, which included a bounty for male scalps or prisoners. Also during the Seven Years' War, Governor of Nova Scotia Charles Lawrence offered a reward for male Mi'kmaq scalps in 1756.[26] (In 2000, some Mi'kmaq argued that this proclamation was still legal in Nova Scotia. Government officials argued that it was no longer legal because the bounty was superseded by later treaties - see the Halifax Treaties).[27]

During the French and Indian War, as of June 12, 1755, Massachusetts governor William Shirley was offering a bounty of £40 for a male Indian scalp, and £20 for scalps of females or of children under 12 years old.[21][28] In 1756, Pennsylvania Lieutenant Governor Robert Morris, in his Declaration of War against the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) people, offered "130 Pieces of Eight, for the Scalp of Every Male Indian Enemy, above the Age of Twelve Years," and "50 Pieces of Eight for the Scalp of Every Indian Woman, produced as evidence of their being killed."[21][29]

American Revolution

In the American Revolutionary War, Henry Hamilton, the British Lieutenant Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs at Fort Detroit, was known by American Patriots as the "hair-buyer general" because they believed he encouraged and paid his Native American allies to scalp American settlers. When Hamilton was captured in the war by the colonists, he was treated as a war criminal instead of a prisoner of war because of this. However, American historians have conceded that there was no positive proof that he had ever offered rewards for scalps.[30] It is now assumed that during the American Revolution, no British officer paid for scalps.[31] During the Sullivan Expedition, the September 13, 1779 journal entry of Lieutenant William Barton tells of patriots participating in scalping.[32]

Mexico

In 1835, the government of the Mexican state of Sonora put a bounty on the Apache which,[33] over time, evolved into a payment by the government of 100 pesos for each scalp of a male 14 or more years old . In 1837, the Mexican state of Chihuahua also offered a bounty on Apache scalps, 100 pesos per warrior, 50 pesos per woman, and 25 pesos per child.[33] Harris Worcester wrote: "The new policy attracted a diverse group of men, including Anglos, runaway slaves led by Seminole John Horse, and Indians — Kirker used Delawares and Shawnees; others, such as Terrazas, used Tarahumaras; and Seminole Chief Coacoochee led a band of his own people who had fled from Indian Territory."[34]

American Civil War

Some scalping incidents even occurred during the American Civil War. For example, Confederate guerrillas led by "Bloody Bill" Anderson were well known for decorating their saddles with the scalps of Union soldiers they had killed.[35] Archie Clement had the reputation of being Anderson's “chief scalper”.

Continued Indian Wars

In 1851, the U.S. Army displayed Indian scalps in Stanislaus County, California. In Tehama County, California, U.S. military and local volunteers razed villages and scalped hundreds of men, women, and children.[36]

Scalping also occurred during the Sand Creek Massacre on November 29, 1864, during the American Indian Wars, when a 700-man force of U.S. Army volunteers destroyed the village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating[37][38] an estimated 70–163 Native Americans.[39][40][41] An 1867 New York Times article reported that "settlers in a small town in Colorado Territory had recently subscribed $5,000 to a fund ‘for the purpose of buying Indian scalps (with $25 each to be paid for scalps with the ears on)’ and that the market for Indian scalps ‘is not affected by age or sex’." The article noted this behavior was "sanctioned" by the U.S. federal government, and was modeled on patterns the U.S. had begun a century earlier in the "American East".[42]:206

From one writer's point of view, it was a "uniquely American" innovation that the use of scalp bounties in the wars against indigenous societies "became an indiscriminate killing process that deliberately targeted Indian non-combatants (including women, children, and infants), as well as warriors."[42]:204

Image gallery

Scalped corpse of buffalo hunter Ralph Morrison found after an 1868 encounter with Cheyennes, near Fort Dodge, Kansas

Scalped corpse of buffalo hunter Ralph Morrison found after an 1868 encounter with Cheyennes, near Fort Dodge, Kansas Skull of a 20- to 30-year-old decapitated woman of the 3rd century CE. Cutting marks above the right eye hole show the head has been scalped.

Skull of a 20- to 30-year-old decapitated woman of the 3rd century CE. Cutting marks above the right eye hole show the head has been scalped. Scalp

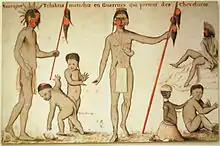

Scalp Sauvage matachez en Guerrier (1732), by Alexandre de Batz

Sauvage matachez en Guerrier (1732), by Alexandre de Batz Josiah P. Wilbarger being scalped by Comanche Indians, 1833

Josiah P. Wilbarger being scalped by Comanche Indians, 1833 Lithograph depiction of scalping, circa 1850s

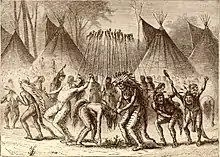

Lithograph depiction of scalping, circa 1850s Modocs scalping and torturing prisoners, published in May 1873

Modocs scalping and torturing prisoners, published in May 1873 The remains of dead Crow Indians killed and scalped by Piegan Blackfeet c. 1874

The remains of dead Crow Indians killed and scalped by Piegan Blackfeet c. 1874 Survivor Robert McGee was scalped as a child in 1864 by Sioux —photo c. 1890.

Survivor Robert McGee was scalped as a child in 1864 by Sioux —photo c. 1890. 1864 photo of Californian Seth Kinman displaying an Indian scalp (front left). He collected "Indian artifacts" including scalps.

1864 photo of Californian Seth Kinman displaying an Indian scalp (front left). He collected "Indian artifacts" including scalps. Native American Big Mouth Spring with decorated scalp lock on right shoulder. 1910 photograph by Edward S. Curtis

Native American Big Mouth Spring with decorated scalp lock on right shoulder. 1910 photograph by Edward S. Curtis Modern roadside historical marker in Boscawen, New Hampshire about the 1697 scalping incident involving Hannah Duston

Modern roadside historical marker in Boscawen, New Hampshire about the 1697 scalping incident involving Hannah Duston Indian Warrior with Scalp (1789), by Barlow

Indian Warrior with Scalp (1789), by Barlow

See also

References

- Griffin, Anastasia M. (2008). Georg Friederici's (1906) "Scalping and Similar Warfare Customs in America" with a Critical Introduction. ProQuest. ISBN 9780549562092 p.18.

- Mensforth, Robert P.; Chacon, Richard J. Chacon; Dye, David H. (2007). "Human Trophy Taking in Eastern North America During the Archaic Period: The Relationship to Warfare and Social Complexity". The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians. Springer Science + Business Media. p. 225.

- "V2*Vault Shutdown | Canvas @ Yale". Archived from the original on 2017-08-20. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- Griffin, Anastasia M. (editor); Frederici, Georg (2008). "Critical Introduction". Scalping and Similar Warfare Customs in America. p. 180. ISBN 9780549562092.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Herodotus; De Selincourt, Aubrey (translator) (2003). The Histories. London: Penguin Books. pp. 260–261.

- Marcellinus, Ammianus; Yonge, C.D. (1862). Roman History, Book XXXI, II. London: Bohn. p. 22.

- Domenech, Abbe Emmanuel (1860). Seven Years' Residence in the Great Deserts of North America, Vol. 2. London: Longman Green. p. 358.

- Crouch, Jace. The Judicial Punishment of Delcavatio in Visigothic Spain: A Proposed Solution based on Isidore of Seville and the Lex Visigothorum. pp. 1–5. and Abstract.

- Duncan, John (1847). Travels in Western Africa in 1845 & 1846, Comprising a Journey from Whydah, through the Kingdom of Dahomey, to Adofoodia, in the Interior, Vol. I. London: Richard Bentley. pp. 233–234.

- Duncan, John (1847). Travels in Western Africa in 1845 & 1846, Comprising a Journey from Whydah, through the Kingdom of Dahomey, to Adofoodia, in the Interior, Vol. II. London: Richard Bentley. pp. 274–275.

- Burton, Richard F. (February 1864). Anthropological Review, Vol. 2, No. 4. pp. 50–51.

- Griffin, Anastasia M. (editor); Friederici, Georg (2008). "Scalping and Similar Warfare Customs in America". pp. 63–70. ISBN 9780549562092.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- van de Logt, Mark (2012). War Party in Blue: Pawnee Scouts in the U.S. Army. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0806184395.

- Hall Steckel, Richard; R. Haines, Michael (2000). A population history of North America. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-521-49666-7.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Beacon Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8070-0040-3.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890. ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 708. ISBN 978-1851096978.

- "The Jesuit Relations: Index". Puffin.creighton.edu. 11 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-03-21. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- Grenier. 2005. p.39

- MacLellan, Louisbourg ("Appendix: Scalping"); John Grenier (2005). "The First Way of War: American War Making On the Frontier, 1607-1814". Cambridge University Press.

- Grenier, John. First Way of War. p. 39.

- "Scalping, Torture, and Mutilation by Indians". Blue Corn Comics. Archived from the original on 2016-08-31. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- Williamson, William. The History of the State of Maine, Vol 2. pp. 117–118.

- Drake, Samuel Gardner & Shirley, William (1870). A particular history of the five years French and Indian War in New England ... p. 134.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- O'Toole, Fintan (2005). White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America. ISBN 9780374281281.

- John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press. 2008

- "Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society". Archive.org. Halifax. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- "Two hundred year-old scalp law still on books in Nova Scotia - Canada - CBC News". Cbc.ca. 2000-01-04. Archived from the original on 2016-05-18. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- Liz Sonneborn (2014-05-14). Chronology of American Indian History. p. 88. ISBN 9781438109848. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- "Declaration of War". simpson.edu. 7 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014.

- Arthur, Elizabeth (1979). "Hamilton, Henry". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Kelsey pg. 303

- "Journals of the military expedition of Major General John Sullivan against the Six nations of Indians in 1779; with records of centennial celebrations; prepared pursuant to chapter 361, laws of the state of New York, of 1885". Archive.org. Auburn, N.Y., Knapp, Peck & Thomson, Printers. 1887. Archived from the original on 2016-03-22. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- Haley, James L. (1981). Apaches: A History and Culture Portrait. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 51. ISBN 0806129786.

- Worcester, Donald Emmet (1985). Pioneer Trails West. Caxton Press. p. 93. ISBN 0870043048.

- "William "Bloody Bill" Anderson . Jesse James . WGBH American Experience". PBS.org. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- Pfaelzer, Jean (2007). Driven Out: The Forgotten War against Chinese Americans. New York: Random House.

- Jackson, Helen (1994). A Century of Dishonor. United States: Indian Head Books. p. 344. ISBN 1-56619-167-X.

- Hoig, Stan (2005) [1974]. The Sand Creek Massacre. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8061-1147-6.

- Brown, Dee (2001) [1970]. "War Comes to the Cheyenne". Bury my heart at Wounded Knee. Macmillan. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-8050-6634-0.

- "THE WEST - Who is the Savage?". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 2016-07-26. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- "John Evans Study Report". University of Denver. November 2014. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Kakel, Carroll P. (2011). The American West and the Nazi East, A Comparative and Interpretive Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bibliography

- Axtell, James. "Scalps and Scalping". Encyclopedia of North American Indians.

- Burton, Richard F. (1864). "Notes on Scalping". Anthropological Review. II: 49–52.

- Arthur, Elizabeth (1979). "Hamilton, Henry". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma Press.

- Grenier, John (2005). The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier. Cambridge University Press.

- Griffin, Anastasia M. (2008). Georg Friederici's (1906) "Scalping and Similar Warfare Customs in America" with a Critical Introduction. p. 248. ISBN 9780549562092.

- Kelsey, Isabel (1984). Joseph Brant 1743–1807: Man of Two Worlds. ISBN 0-8156-0182-4.

- Mensforth, Robert P.; Chacon, Richard J. (editor); Dye, David H. (editor) (2007). "Human Trophy Taking in Eastern North America During the Archaic Period: The Relationship to Warfare and Social Complexity". The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians. Springer Science + Business Media: 225.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scalping. |

- Axtell, James & Sturtevant, William. "The Unkindest Cut, or Who Invented Scalping" (PDF). Amstudy.hku.hk.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cowan, Ross. "Head-Hunting Roman Cavalry". Academia.edu.

- Lawrence, Charles, Governor (1756). "British Scalp Proclamation". We Were Not the Savages: First Nation History.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)