Scratch (programming language)

Scratch is a block-based visual programming language and website targeted primarily at children 8-16 as an educational tool for coding.[5][6] Users of the site can create projects on the web using a block-like interface. The service is developed by the MIT Media Lab, has been translated into 70+ languages, and is used in most parts of the world.[7] Scratch is taught and used in after-school centers, schools, and colleges, as well as other public knowledge institutions. As of January 2021, community statistics on the language's official website show more than 67 million projects shared by over 64 million users, and almost 38 million monthly website visits.[7]

| |

| Paradigm | Event-driven, visual, block-based programming language |

|---|---|

| First appeared | 2003 (first prototype) 2004 (second prototype) May 15, 2007 (public launch)[1] May 9, 2013 (Scratch 2.0) January 2, 2019 (Scratch 3.0) |

| Implementation language | Squeak (Scratch 0.x, 1.x) ActionScript (Scratch 2.0) JavaScript (Scratch 3.0) |

| OS | Microsoft Windows, macOS, Linux (via renderer), HTML5, iOS, iPadOS, and Android. |

| License | GPLv2 and Scratch Source Code License |

| Filename extensions | .scratch (Scratch 0.x) .sb, .sprite (Scratch 1.x) .sb2, .sprite2 (Scratch 2.0) .sb3, .sprite3 (Scratch 3.0) |

| Website | scratch |

| Influenced by | |

| Logo, Smalltalk, HyperCard, StarLogo, AgentSheets, AgentCubes, Etoys | |

| Influenced | |

| ScratchJr,[2] Snap!,[3][4] mBlock | |

Scratch takes its name from a technique used by disk jockeys called "scratching", where vinyl records are clipped together and manipulated on a turntable to produce different sound effects and music. Like scratching, the website lets users mix together different media (including graphics, sound, and other programs) in creative ways by creating and remixing projects, like video games, animations, and simulations.[8][9]

Scratch 3.0

User interface

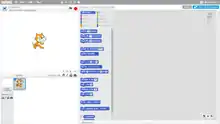

The Scratch interface is divided into three main sections: a stage area, block palette, and a coding area to place and arrange the blocks into scripts that can be run by pressing the green flag or clicking on the code itself. Users may also create their own code blocks and they will appear in "My Blocks".

The stage area features the results (e.g., animations, turtle graphics, either in a small or normal size, with a full-screen option also available) and all sprites thumbnails being listed in the bottom area. The stage uses x and y coordinates, with 0,0 being the stage center.[10]

With a sprite selected at the bottom of the staging area, blocks of commands can be applied to it by dragging them from the block palette into the coding area. The Costumes tab allows users to change the look of the sprite in order to create various effects, including animation.[10] The Sounds tab allows attaching sounds and music to a sprite.[11]

When creating sprites and backgrounds, users can draw their own sprite manually,[10] choose a Sprite from the library, or upload an image.[11]

The table below shows the categories of the programming blocks:

| Category | Notes | Category | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | Movements of sprites like angles and position | Sensing | Sprites can interact with the surroundings | |||

| Looks | Controls the visuals of the sprite | Operators | Mathematical operators, comparisons | |||

| Sound | Plays audio files and effects | Variables | Variable and List usage and assignment | |||

| Events | Event handlers | My Blocks | Allows defining functions which have no return value | |||

| Control | Conditionals and loops etc. | Extensions | Explained [#Extensions_2 below] | |||

Offline editing

An offline "desktop editor" is available for Microsoft Windows 10 in Microsoft store and Apple's macOS 10.13;[12] this allows the creation and playing of Scratch programs offline. The offline editor can also be downloaded in previous versions, such as Scratch 2.0 and Scratch 1.4.

Extensions

In Scratch, extensions add extra blocks and features that can be used in projects. In Scratch 2.0 and 3.0, the extensions were all hardware-based. Software-based extensions were added in Scratch 3.0, such as text-to-speech voices, along with some new hardware-based extensions like the micro:bit. The extensions are listed below.

Music, Pen, Video Sensing, Text to Speech, Translate, BBC Micro:bit, LEGO Mindstorms EV3, LEGO WeDo 2.0, Makey Makey, LEGO SPIKE Prime, LEGO BOOST, and Go Direct Force & Acceleration

Physical

- Lego Mindstorms EV3 – control motors and receive sensor data from the Lego Mindstorms EV3

- Makey Makey – use the Makey Makey to control projects

- Lego Education WeDo 2.0 – control motors and receive sensor data from the Lego WeDo

- Lego Education SPIKE Prime—The main programming language for the Lego SPIKE Prime, including motor control and receiving sensor data

- BBC micro:bit – use of a BBC micro:bit to control projects

- Lego BOOST – bring robotic creations to life

- Go Direct Force & Acceleration – Sense pull, push, motion, and spin.

Digital

Many of the digital extensions in Scratch 3.0 used to be regular block categories that were moved to the extensions section to reduce clutter. These include:

- Music – Play digital instruments (drums, trumpets, violins, pianos and more)

- Pen – Draw on the Stage with a variety of thicknesses and color

- Video Sensing – Detect motion with the camera.

New digital extensions have also been added in collaborations with commercial companies. These include:

- Text to Speech – Converts words in a text into voice output (variety of voices, supplied by Amazon)

- Translate – Uses Google Translate to translate text from one language into a variety of other languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, English, French, Greek, and Japanese

Users can also create their own extensions for Scratch 3.0 using JavaScript.[13]

Community of users

_2007.PNG.webp)

Scratch is used in many different settings: schools, museums, libraries, community centers, and homes.[17][18][8] Although Scratch's target group is 8–16-year-old school pupils,[19] it is used by all ages including educators and parents. This wide outreach has created many surrounding communities, both physical and digital.[7] In April 2020, the Tiobe ranking of the world's programming languages included Scratch into the top 20. According to Tiobe, there are 50 million projects written in Scratch, and every month one million new projects are added.[20]

Educational users

Scratch is popular in the United Kingdom and United States through Code Clubs. Scratch is used as the introductory language because the creation of interesting programs is relatively easy, and skills learned can be applied to other programming languages such as Python and Java.

Scratch is not exclusively for creating games. With the provided visuals, programmers can create animations, text, stories, music, and more. There are already many programs which students can use to learn topics in math, history, and even photography. Scratch allows teachers to create conceptual and visual lessons and science lab assignments with animations that help visualize difficult concepts. Within the social sciences, instructors can create quizzes, games, and tutorials with interactive elements. Using Scratch allows young people to understand the logic of programming and how to creatively build and collaborate.[21]

Scratch is taught to more than 800 schools and 70 colleges of DAV organization in India and across the world.[22][23]

In higher education, Scratch is used in the first week of Harvard University's CS50 introductory computer science course.[24][25]

Online community

On Scratch, members have the capability to share their projects and get feedback. Projects can be uploaded directly from the development environment to the Scratch website and any member of the community can download the full source code to study or to remix into new projects.[26][27] Members can also create project studios, comment, tag, favorite, and "love" others' projects, follow other members to see their projects and activity, and share ideas. Projects range from games to animations to practical tools. Additionally, to encourage creation and sharing amongst users, the website frequently establishes "Scratch Design Studio" challenges.[28]

The MIT Scratch Team works to ensure that this community maintains a friendly and respectful environment for all people.[29][30]

Educators have their own online community called ScratchEd, developed and supported by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. In this community, Scratch educators share stories, exchange resources, and ask questions.[31]

Scratch Wiki

The Scratch Wiki is a support resource for Scratch and its website, history, and phenomena surrounding it. Although supported by the Scratch Team (developers of Scratch), it is primarily written by Scratchers (users of Scratch) for information regarding the program and website.[32]

Events

Scratch Educators can gather in person at Scratch Educator Meetups. At these gatherings, Scratch Educators learn from each other and share ideas and strategies that support computational creativity.[35]

An annual "Scratch Day" is declared in May each year. Community members are encouraged to host an event on or around this day, large or small, that celebrates Scratch. These events are held worldwide, and a listing can be found on the Scratch Day website.[36]

History

The MIT Media Lab's Lifelong Kindergarten group, led by Mitchel Resnick, in partnership with the Montreal-based consulting firm, the Playful Invention Company, co-founded by Brian Silverman and Paula Bonta, together developed the first desktop-only version of Scratch in 2003. It started as a basic coding language, with no labeled categories and no green flag.[37] Scratch was made with the intention to teach kids to code.[37]

The philosophy of Scratch encourages the sharing, reuse, and combination of code, as indicated by the team slogan, "Imagine, Program, Share".[38] Users can make their own projects, or they may choose to "remix" someone else's project. Projects created and remixed with Scratch are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.[39] Scratch automatically gives credit to the user who created the original project and program in the top part[8]

Scratch was developed based on ongoing interaction with youth and staff at Computer Clubhouses. The use of Scratch at Computer Clubhouses served as a model for other after-school centers demonstrating how informal learning settings can support the development of technological fluency.[40]

Scratch 2.0 was released on May 9, 2013.[10] The update changed the look of the site and included both an online project editor and an offline editor.[41] Custom blocks could now be defined within projects, along with several other improvements.[42] The Scratch 2.0 Offline editor could be downloaded for Windows, Mac and Linux directly from Scratch's website, although support for Linux was later dropped. The unofficial mobile version had to be downloaded from the Scratch forums.[43][44]

Scratch 3.0 was first announced by the Scratch Team in 2016. Several public alpha versions were released between then and January 2018, after which the pre-beta "Preview" versions were released.[45] A beta version of Scratch 3.0 was released on 1 August 2018[46] for use on most browsers; with the notable exception of Internet Explorer.[47]

Scratch 3.0, the first 3.x release version, was released on 2 January 2019.

Filetypes

In version 1.4, an .sb file was the file format used to store projects.[48]

An .sb file is divided into four sections:

- "header", this 10-byte header contains the ASCII string 'ScratchV02' in versions higher than 1.2, and 'ScratchV01' in versions 1.2 and below

- "infoSize", encodes the length of the project's infoObjects. A four-byte long, 32-bit, big-Endian integer.

- "infoObjects", a dictionary-format data section. It contains: "thumbnail", a thumbnail of the project's stage; "author", the username of the project's creator; "comment", the Project Notes; "history", the save and upload log; "scratch-version", the version of Scratch used to save the file;

- "contents", an object table with the Stage as the root. All objects in the program are stored here as references.

Version 2.0 uses the .sb2 file format. These are zip files containing a .json file as well as the contents of the Scratch project including sounds (stored as .wav) and images (stored as .png).[49] Each filetype, excluding the project.json, is stored as a number, starting at 0 and counting up with each additional file. The image file labeled '0.png' is always a 480x360 white image, but '0.wav' will still be the earliest non-deleted file.

The ScratchX experimental version of Scratch used the .sbx file format.[50]

Scratch 3.0 uses the .sb3 format, which is very similar to .sb2.[51], one difference being the sound.

Older versions

Although the main Scratch website now runs only the current version (3.0), the offline editors for Scratch 2.0 (and the earlier 1.4) are still available for download[52] and can be used to create and run games locally.[53] You can still upload projects from the 2.0 launcher.

Technology

Scratch 2.0 relied on Adobe Flash for the online version, and Adobe AIR for the offline editor. These have fallen out of favor,[54] and Adobe has dropped support for them at the end of 2020.[55]

Interface

In Scratch 2.0, the stage area is on the left side, with the programming blocks palette in the middle the coding area on the right. Extensions are in the "More blocks" section of palette.[6]

The blocks palette in Scratch 2.0 is made of discrete sections that are not scrollable from one to the next; the table below shows the different sections:

| Category | Notes | Category | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | Moves and changes position of sprites | Events | Event handlers | |||

| Looks | Controls the visuals of the sprite | Control | Conditionals and loops | |||

| Sound | Audio files, sequences | Sensing | Sprite interaction | |||

| Pen | Draw on the canvas | Operators | Mathematical operators | |||

| Data | Variables and Arrays | More Blocks | Functions, return value is always void | |||

1.4 sounds

With the 2.0 scratch update, changing how sounds were imported many 1.4 sounds stopped working. (The sound file was changed from .sb to .sb2).

Extensions

In Scratch 2.0, extensions were all hardware based.

Features and derivatives

Scratch uses event-driven programming with multiple active objects called sprites.[10] Sprites can be drawn, as vector or bitmap graphics, from scratch in a simple editor that is part of Scratch, or can be imported from external sources. Scratch 3 only supports one-dimensional arrays, known as "lists", and floating point scalars and strings are supported, but with limited string manipulation ability. There is a strong contrast between the powerful multimedia functions and multi-threaded programming style and the rather limited scope of the Scratch programming language.

The 2.0 version of Scratch does not treat procedures as first class structures and has limited file I/O options with Scratch 2.0 Extension Protocol, an experimental extension feature that allows interaction between Scratch 2.0 and other programs.[56] The Extension protocol allows interfacing with hardware boards such as Lego Mindstorms[57] or Arduino.[58] Version 2 of Scratch was implemented in ActionScript, with an experimental JavaScript-based interpreter being developed in parallel.[59]

Version 1.4 of Scratch was based on Squeak, which is based on Smalltalk-80. A number of Scratch derivatives[60] called Scratch Modifications have been created using the source code of Scratch version 1.4. These programs are a variant of Scratch that normally include a few extra blocks or changes to the GUI.[61]

Snap! (Build Your Own Blocks)

A more advanced visual programming language inspired by Scratch is Snap!, featuring first class procedures (their mathematical foundations are called also lambda calculus), first class lists (including lists of lists), and first class truly object oriented sprites with prototyping inheritance, and nestable sprites, which are not part of Scratch.[62] Snap! (previously "BYOB") was developed by Jens Mönig[63][64] with documentation provided by Brian Harvey[65][66] from University of California, Berkeley and has been used to teach "The Beauty and Joy of Computing" introductory course in CS for non-CS-major students.[67] Both of them were members of the Scratch Team before designing "Snap!".[68][6]

Censorship

In August 2020, GreatFire announced that the Chinese Government has blocked access to Scratch. At the time, it was estimated that more than 3 million people from China were using it.[70][71] Later, a state-run Chinese outlet states that Scratch features "humiliating, fake and libellous content about China". The outlet cited for example the fact that Macao, Hong Kong and Taiwan are listed as countries on the website.[72]

See also

- Blockly, interface used by Scratch to make the code blocks

- Code.org

- Computer Clubhouse

- Programmable Cricket

- PWCT (software)

- Squeak

- Visual programming language

References

- "Scratch Timeline - Scratch Wiki". en.scratch-wiki.info.

- "ScratchJr - Home". scratchjr.org.

- "Snap! Build Your Own Blocks". snap.berkeley.edu.

- "Snap! Build Your Own Blocks". snap.berkeley.edu.

- Maloney, John; Resnick, Mitchel; Rusk, Natalie; Silverman, Brian; Eastmond, Evelyn (2010). "The Scratch Programming Language and Environment" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Computing Education. 10 (4): 1–15. doi:10.1145/1868358.1868363. ISSN 1946-6226. S2CID 9744698.

- Resnick, Mitchel; Maloney, John; Hernández, Andrés; Rusk, Natalie; Eastmond, Evelyn; Brennan, Karen; Millner, Amon; Rosenbaum, Eric; Silver, Jay; Silverman, Brian; Kafai, Yasmin (2009). "Scratch: Programming for All" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 52 (11): 60–67. doi:10.1145/1592761.1592779.

- "Community statistics at a glance". scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Lamb, Annette; Johnson, Larry (April 2011). "Scratch: Computer Programming for 21st Century Learners" (PDF). Teacher Librarian. 38 (4): 64–68. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Schorow, Stephanie (14 May 2007). "Creating from Scratch". MIT News. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Marji, Majed (2014). Learn to Program with Scratch. San Francisco, California: No Starch Press. pp. xvii, 1–9, 13–15. ISBN 978-1-59327-543-3.

- "Science Buddies: Scratch User Guide: Installing & Getting Started with Scratch". ScienceBuddies.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch Desktop". Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "Scratch 3.0 Extensions". Github. MIT. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Pasternak, Erik (17 January 2019). "Scratch 3.0's new programming blocks, built on Blockly". Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Frang, Corey (28 February 2019). "Porting Scratch from Flash to Javascript". Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Blockly". Google Developers.

- Oliveira, Michael (30 April 2014). "Canadian schools starting to teach computer coding to kids". CTV.ca. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch Day". Science Museum of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch - About". scratch.mit.edu.

- Fay, Joe (6 April 2020). "Kids programming language Scratch nails top 20 in latest dev rankings • DEVCLASS". DEVCLASS. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Martin, Neil (25 June 2015). "What is Scratch? Is it AV or IT?". AV Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "DAV CS Syllabus" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "DAV Jharkhand Syllabus". Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Young, Jeffrey R. (20 July 2007). "Fun, Not Fear, Is at the Heart of Scratch, a New Programming Language". The Chronicle of Higher Education. ISSN 0009-5982. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "CS50 Syllabus". Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Monroy-Hernandez, Andres; Hill, Benjamin Mako; Gonzalez-Rivero, Jazmin; Boyd, Danah (2011). "Computers Can't Give Credit: How Automatic Attribution Falls Short in an Online Remixing Community". Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '11). ACM. pp. 3421–30. arXiv:1507.01285. doi:10.1145/1978942.1979452. S2CID 7494330.

- Hill, B.M; Monroy-Hernández, A.; Olson, K.R. (2010). "Responses to remixing on a social media sharing website". ICWSM 2010 : Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, May 23–26, 2010. Washington, D.C.: AAAI Press. arXiv:1507.01284. Bibcode:2015arXiv150701284M. ISBN 978-1-57735-445-1. OCLC 844857775.

- "Scratch Design Studio". wiki.scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "For Parents". scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch Community Guidelines". scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch for Educators". scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Scratch Wiki". en.scratch-wiki.info. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "LLK/scratch-gui". 9 January 2021 – via GitHub.

- "Scratch - Developers". scratch.mit.edu.

- "Scratch Educator". Meetup.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch Day". Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Development of Scratch 1.0". en.scratch-wiki.info. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch – Imagine, Program, Share". scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Creative Commons License". wiki.scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "ITR: A Networked, Media-Rich Programming Environment to Enhance Informal Learning and Technological Fluency at Community Technology Centers". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch Desktop". scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Biggs, John (10 May 2013). "Kids' Programming Tool Scratch Now Runs In The Browser". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Updated Scratch 2.0 Offline (Beta) is now available!". Scratch. 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch 2.0 Preview". YouTube. MITScratchTeam. 1 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch 3.0". en.scratch-wiki.info. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "3 Things To Know About Scratch 3.0". Medium.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch 3.0". scratch.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch Wiki - .sb". 4 October 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- "Scratch File Format (2.0)". Scratch Wiki. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "LLK/scratchx". GitHub.

- "Scratch File Format". Scratch Wiki. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "Scratch 2.0 Offline Editor". MIT. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "3 Things To Know About Scratch 3.0". The Scratch Team. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- O'Donnell, Lindsey (14 January 2019). "Mozilla Kills Default Support for Adobe Flash in Firefox 69". Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Adobe Corporate Communications (30 May 2019). "The Future of Adobe AIR". Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Scratch Extension". MIT. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "EV3+Scratch Extension". Scratch extension GitHub. Code & Circuit. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Preliminary Scratch extension for talking to Arduino boards running Firmata". Scratch extension GitHub. Damellis. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "We're seeking contributors to help finish our HTML5 Scratch player (now open sourced!)". Scratch. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Scratch Modification". Scratch Wiki. Lifelong Kindergarten Group at the MIT Media Lab. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Blocks". Scratch Wiki. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Snap! — Build Your Own Blocks". University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Mönig, Jens. "Jens on Scratch". Scratch. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Mönig, Jens (31 May 2011). "BYOB 3.1 – Prototypal Inheritance for Scratch". Chirp Blog. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Brian Harvey". Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "bharvey". Scratch. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "CS10 : The Beauty and Joy of Computing". EECS Instructional Support Group Home Page. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Relationship With the Scratch Team".

- "About ScratchJr". scratchjr.org. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "China bans Scratch, MIT's programming language for kids". TechCrunch. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "China appears to be blocking access to children's programming language Scratch - Computer - News". World Today News. 7 September 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "China blocks MIT's kid-friendly programming language Scratch". Developer Tech News. 8 September 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

External links

Scratch at Wikibooks

Scratch at Wikibooks Media related to Scratch (programming language) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Scratch (programming language) at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Scratch at Curlie