Second-order cybernetics

Second-order cybernetics, also known as the cybernetics of cybernetics, is the recursive application of cybernetics to itself and the practice of cybernetics according to such a critique. It was developed between approximately 1968 and 1975 by Margaret Mead, Heinz von Foerster and others.[1] Von Foerster referred to it as the cybernetics of "observing systems" whereas first order cybernetics is that of "observed systems".[2] It is sometimes referred to as the "new cybernetics", the term preferred by Gordon Pask, and is closely allied to radical constructivism, which was developed around the same time by Ernst von Glasersfeld.[3] While it is sometimes considered a radical break from the earlier concerns of cybernetics, there is much continuity with previous work and it can be thought of as the completion of the discipline, responding to issues evident during the Macy conferences in which cybernetics was initially developed.[4] Its concerns include epistemology, ethics, autonomy, self-consistency, self-referentiality, and self-organizing capabilities of complex systems. It has been characterised as cybernetics where "circularity is taken seriously".[5]

Cybernetics of cybernetics and the new cybernetics

Second-order Cybernetics can be abbreviated as C2 or SOC, and is sometimes referred to as the cybernetics of cybernetics, the new cybernetics or second cybernetics.[6] The terms are often used interchangeably, but can also stress different aspects:

- Most commonly, second-order cybernetics refers to the practice of cybernetics where cyberneticians understand themselves to be part of the system they study. This is strongly associated with Heinz von Foerster.

- More specifically, and especially where phrased as the cybernetics of cybernetics, it refers to the recursive application of cybernetics to itself and the practice of cybernetics in accordance with its own ideas. This is closely associated with Mead's 1967 address to the American Society for Cybernetics (published 1968)[7] and von Foerster's "Cybernetics of Cybernetics"[8] book, developed as a course option at the Biological Computer Laboratory (BCL), where Cybernetic texts were analysed according to the principles they put forward.

- Most generally, and especially where referred to as the new cybernetics, it signifies substantial developments in direction and scope taken by the field following the above critiques.[6]

Initial development

Second-order cybernetics took shape during the late 1960s and mid 1970s. The 1967 keynote address to the inaugural meeting of the American Society for Cybernetics (ASC) by Margaret Mead, who had been a participant at the Macy Conferences, is a defining moment in its development. She characterised "cybernetics as a way of looking at things and as a language for expressing what one sees".[7] This paper was social[9] and ecological[1] in focus, with Mead calling on cyberneticians to assume responsibility for the social consequences of the language of cybernetics and the development of cybernetic systems.[9]

Mead's paper concluded with a proposal directed at the ASC itself, that it organise itself in the light of the ideas with which it was concerned. That is, the practice of Cybernetics by the ASC should be subject to Cybernetic critique, an idea returned to specially by Ranulph Glanville in his time as president of the society.[10][11]

Mead's paper was published in 1968 in a collection edited by Heinz von Foerster.[7] With Mead uncontactable due to field work at the time, von Foerster titled the paper "Cybernetics of Cybernetics",[12] a title that perhaps emphasised his concerns more than Mead's.[1] Von Foerster promoted Second-order Cybernetics energetically, developing it as a means of renewal for Cybernetics generally and as what has been called an "unfinished revolution" in science.[13] Von Foerster developed Second-order Cybernetics as a critique of realism and objectivity and as a radically reflexive form of science, where observers enter their domains of observation, describing their own observing not the supposed causes.[9]

The initial development of second-order cybernetics was consolidated by the mid 1970s in a series of significant developments and publications:

- The 1974 publication of the "Cybernetics of Cybernetics" book, edited by Von Foerster.[8] This was developed as a course option at the BCL and involved the examination of various texts from Cybernetics according to the principals they proposed. Here von Foerster defined Cybernetics of Cybernetics as "the control of control and the communication of communication" and differentiated first order cybernetics as "the cybernetics of observed systems" and second order cybernetics as "the cybernetics of observing systems".[8]

- Autopoiesis, developed by biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela.[14]

- Conversation theory, developed by Gordon Pask, Bernard Scott and Dionysius Kallikourdis.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

- Glanville's theory of objects, developed in his (first) PhD thesis, supervised by Pask and examined by von Foerster.[21]

- Radical constructivism, developed by Ernst von Glasersfeld.[22]

- Eigen-Forms, developed by von Foerster.[23]

Relationship to "first order" cybernetics

Heinz von Foerster attributes the origin of second-order cybernetics to the attempts by cyberneticians to construct a model of the mind:

... a brain is required to write a theory of a brain. From this follows that a theory of the brain, that has any aspirations for completeness, has to account for the writing of this theory. And even more fascinating, the writer of this theory has to account for her or himself. Translated into the domain of cybernetics; the cybernetician, by entering his own domain, has to account for his or her own activity. Cybernetics then becomes cybernetics of cybernetics, or second-order cybernetics.[24]

Many cyberneticians draw a sharp distinction between first and second order cybernetics, others stress the continuity between the two, and the implicit second order qualities of earlier cybernetics.[25][26][27][28]

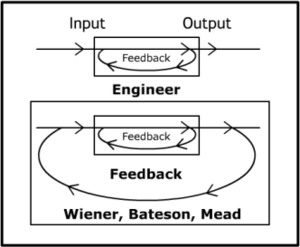

The anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead contrasted first and second-order cybernetics with this diagram in an interview in 1973.[29] Referring to the Macy conferences, it emphasises the requirement for a participant observer in the second order case:

- ... essentially your ecosystem, your organism-plus-environment, is to be considered as a single circuit.[29]

In 1992, Pask summarized the differences between the old and the new cybernetics as a shift in emphasis:.[30][31]

- ... from information to coupling

- ... from the reproduction of "order-from-order" (Schroedinger 1944) to the generation of "order-from-noise" (von Foerster 1960)

- ... from transmission of data to conversation

- ... from external observation to participant observation – an approach that could be assimilated to Maturana and Varela's concept of autopoiesis.

Topics

In biology

Some biologists influenced by cybernetic concepts (Maturana and Varela, 1980; Varela, 1979; Atlan, 1979) realized that the cybernetic metaphors of the program upon which molecular biology had been based rendered a conception of the autonomy of the living being impossible. Consequently, these thinkers were led to invent a new cybernetics, one more suited to the organization mankind discovers in nature – organizations he has not himself invented. The possibility that this new cybernetics could also account for social forms of organization, remained an object of debate among theoreticians on self-organization in the 1980s.[32]

In political science

In political science in the 1980s unlike its predecessor, the new cybernetics concerns itself with the interaction of autonomous political actors and subgroups and the practical reflexive consciousness of the subject who produces and reproduces the structure of political community. A dominant consideration is that of recursiveness, or self-reference of political action both with regard to the expression of political consciousness and with the ways in which systems build upon themselves.[33]

In 1978, Geyer and van der Zouwen discuss a number of characteristics of the emerging "new cybernetics". One characteristic of new cybernetics is that it views information as constructed by an individual interacting with the environment. This provides a new epistemological foundation of science, by viewing it as observer-dependent. Another characteristic of the new cybernetics is its contribution towards bridging the "micro-macro gap". That is, it links the individual with the society. Geyer and van der Zouten also noted that a transition from classical cybernetics to new cybernetics involves a transition from classical problems to new problems. These shifts in thinking involve, among other things, a change in emphasis on the system being steered to the system doing the steering, and the factors which guide the steering decisions. And a new emphasis on communication between several systems which are trying to steer each other.[34]

Geyer & J. van der Zouwen (1992) recognize four themes in both sociocybernetics and new cybernetics:[35]

- An epistemological foundation for science as an observer-observer system. Feedback and feedforward loops are constructed not only between the observer, and the objects that are observed them and the observer.

- The transition from classical, rather mechanistic first-order cybernetics to modern, second-order cybernetics, characterized by the differences summarized by Gordon Pask.

- These problem shifts in cybernetics result from a thorough reconceptualization of many all too easily accepted and taken for granted concepts – which yield new notions of stability, temporality, independence, structure versus behaviour, and many other concepts.

- The actor-oriented systems approach, promulgated in 1978 made it possible to bridge the "micro-macro" gap in social science thinking.

Other topics where new cybernetics is developed are:

Organizational cybernetics

Organizational cybernetics is distinguished from management cybernetics. Both use many of the same terms but interpret them according to another philosophy of systems thinking. Organizational cybernetics by contrast offers a significant break with the assumption of the hard approach. The full flowering of organizational cybernetics is represented by Beer's viable system model.[43]

Organizational cybernetics studies organizational design, and the regulation and self-regulation of organizations from a systems theory perspective that also takes the social dimension into consideration. Researchers in economics, public administration and political science focus on the changes in institutions, organisation and mechanisms of social steering at various levels (sub-national, national, European, international) and in different sectors (including the private, semi-private and public sectors; the latter sector is emphasised).[44]

Sociocybernetics

The reformulation of sociocybernetics as an "actor-oriented, observer-dependent, self-steering, time-variant" paradigm of human systems, was most clearly articulated by Geyer and van der Zouwen in 1978 and 1986.[45] They stated that sociocybernetics is more than just social cybernetics, which could be defined as the application of the general systems approach to social science. Social cybernetics is indeed more than such a one-way knowledge transfer. It implies a feed-back loop from the area of application – the social sciences – to the theory being applied, namely cybernetics; consequently, sociocybernetics can indeed be viewed as part of the new cybernetics: as a result of its application to social science problems, cybernetics, itself, has been changed and has moved from its originally rather mechanistic point of departure to become more actor-oriented and observer-dependent.[46] In summary, the new sociocybernetics is much more subjective and uses a sociological approach more than classical cybernetics approach with its emphasis on control. The new approach has a distinct emphasis on steering decisions; furthermore, it can be seen as constituting a reconceptualization of many concepts which are often routinely accepted without challenge.[34]

Criticism

Andrew Pickering has criticised second order cybernetics as a form of linguistic turn, moving away from the performative practices he finds valuable in earlier cybernetics.[47] Pickering's comments seem to apply specifically to where second order cybernetics has emphasised epistemology and language, for instance in the work of von Foerster, as he approvingly references the work of figures such as Bateson and Pask and the idea of participant observers which fall within the scope of second order cybernetics more broadly considered.

See also

References

- Glanville, R. (2002). Second order cybernetics. In F. Parra-Luna (Ed.), Systems science and cybernetics. In Encyclopaedia of life support systems (EOLSS). Oxford: EoLSS. Retrieved from http://www.eolss.net/

- von Foerster, H. (Ed.). (1995). Cybernetics of cybernetics: Or, the control of control and the communication of communication (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Future Systems. (Original work published: 1974).

- Glanville, R. (2013). Radical constructivism = second order cybernetics. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 19(4), 27-42. Retrieved from http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/chk/2012/00000019/00000004/art00003

- Brand, S., Bateson, G., & Mead, M. (1976). For God’s Sake, Margaret: Conversation with Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead. CoEvolutionary Quarterly, 10, 32-44. Retrieved from http://www.oikos.org/forgod.htm

- Glanville, R. (2004). The purpose of second-order cybernetics. Kybernetes, 33(9/10), 1379-1386. doi: 10.1108/03684920410556016

- Gordon Pask. Introduction Different Kinds of Cybernetics. In Gertrudis van de Vijver (Ed) New Perspectives on Cybernetics. Springer Netherlands. pp 11-31.

- Mead, Margaret. "The Cybernetics of Cybernetics." In Purposive Systems, edited by Heinz von Foerster, John D. White, Larry J. Peterson and John K. Russell, 1-11. New York, NY: Spartan Books, 1968.

- von Foerster, Heinz, ed. Cybernetics of Cybernetics: Or, the Control of Control and the Communication of Communication. 2nd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Future Systems, 1995.

- Krippendorff, K. (2008). Cybernetics’s Reflexive Turns. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 15 (3-4), 173-184. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/136

- Glanville, Ranulph. "Introduction: A Conference Doing the Cybernetics of Cybernetics." Kybernetes 40, no. 7/8 (2011): 952-63.

- Glanville, Ranulph, ed. Trojan Horses: A Rattle Bag from the 'Cybernetics: Art, Design, Mathematic – a Meta-Disciplinary Conversation' Post-Conference Workshop. Vienna: Edition echoraum, 2012.

- von Foerster, Heinz. Understanding Understanding: Essays on Cybernetics and Cognition. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2003.

- Müller, Albert, and Karl H. Müller, eds. An Unfinished Revolution? Heinz Von Foerster and the Biological Computer Laboratory (BCL), 1958-1976. Vienna: Edition Echoraum, 2007.

- Varela, Francisco J., Humberto R. Maturana, and R. Uribe. "Autopoiesis: The Organization of Living Systems, Its Characterization and a Model." Biosystems 5, no. 4 (1974): 187-96.

- Pask, Gordon, Bernard Scott, and D. Kallikourdis. "A Theory of Conversations and Individuals (Exemplified by the Learning Process on Caste)." International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 5, no. 4 (1973): 443-566.

- Pask, Gordon, and Bernard Scott. "Caste: A System for Exhibiting Learning Strategies and Regulating Uncertainties." International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 5, no. 1 (1973): 17-52.

- Pask, Gordon, D. Kallikourdis, and Bernard Scott. "The Representation of Knowables." International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 7, no. 1 (1975): 15-134.

- Pask, Gordon. Conversation, Cognition and Learning: A Cybernetic Theory and Methodology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1975.

- Pask, Gordon. Conversation Theory: Applications in Education and Epistemology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1976.

- Pask, Gordon. The Cybernetics of Human Learning and Performance: A Guide to Theory and Research. London: Hutchinson, 1975.

- Glanville, Ranulph. "A Cybernetic Development of Epistemology and Observation, Applied to Objects in Space and Time, as Seen in Architecture: Also Known as the Object of Objects, the Point of Points—or Something About Things." Brunel University, 1975.

- von Glasersfeld, Ernst. "Piaget and the Radical Constructivist Epistemology." In Epistemology and Education, edited by C. D. Smock and Ernst von Glasersfeld, 1-24. Athens, GA: Follow Through Publications, 1974.

- von Foerster, Heinz. "Objects: Tokens for (Eigen-)Behaviors." In Understanding Understanding: Essays on Cybernetics and Cognition, 261-72. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2003.

- Von Foerster 2003, p.289.

- Kline R. R. (2017) The past and the future of second-order cybernetics. In: Riegler A., Müller K. H. & Umpleby S. A. (eds.) New horizons for second-order cybernetics. World Scientific, Singapore: 333–337. Available at https://cepa.info/4104

- Gertrudis van de Vijver (1994), New Perspectives on Cybernetics: Self-Organization, Autonomy and Connectionism, p.97

- Umpleby, S. A. (2016). Second-Order Cybernetics as a Fundamental Revolution in Science. Constructivist Foundations 11(3):455-465.

- Sweeting, B. (2016). Design Research as a Variety of Second-Order Cybernetic Practice. Constructivist Foundations, 11(3), 572-579.

- Interview with Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, CoEvolution Quarterly, June 1973.

- Alessio Cavallaro, Annemarie Jonson, Darren Tofts (2003), Prefiguring Cyberculture: An Intellectual History, MIT Press, p.11.

- Evelyn Fox Keller, "Marrying the premodern to postmodern: computers and organism after World War II", in: M. Norton. Wise eds. Growing Explanations: Historical Perspectives on Recent Science, p 192.

- Jean-Pierre Dupuy, "The autonomy of social reality: on the contribution of systems theory to the theory of society" in: Elias L. Khalil & Kenneth E. Boulding eds., Evolution, Order and Complexity, 1986.

- Peter Harries-Jones (1988), "The Self-Organizing Polity: An Epistemological Analysis of Political Life by Laurent Dobuzinskis" in: Canadian Journal of Political Science , Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun., 1988), pp. 431–433.

- Kenneth D. Bailey (1994), Sociology and the New Systems Theory: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis, p.163.

- R.F. Geyer and G. v.d. Zouwen (1992), "Sociocybernetics", in: Cybernetics and Applied Systems, C.V. Negoita ed. p.96.

- Luciano Floridi (1993), The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Computing and Information, pp.186–196.

- Rachelle A. Dorfman (1988), Paradigms of Clinical Social Work, p.363.

- Policy Sciences, Vol 25, Kluwer Online, p.368

- D. Ray Heisey (2000), Chinese Perspectives in Rhetoric and Communication, p.268.

- Margaret A. Boden (2006), Mind as Machine: A History of Cognitive Science, p.203.

- Loet Leydesdorff (2001), A Sociological Theory of Communication: The Self-Organization of the Knowledge-Based Society. Universal Publishers/uPublish.com. p.253.

- Roland Littlewood, "Social Trends and psychopathology", in: Jonathan C. K. Wells ea. eds., Information Transmission and Human Biology, p. 263.

- Michael C. Jackson (1991), Systems Methodology for the Management Sciences.

- Organisational Cybernetics, Nijmegen School of Management, The Netherlands.

- Lauren Langman, "The family: a 'sociocybernetic' approach to theory and policy", in: R. Felix Geyer & J. van der Zouwen Eds. (1986), Sociocybernetic Paradoxes: Observation, Control and Evolution of Self-Steering Systems, Sage Publications Ltd, pp 26–43.

- R. Felix Geyer & J. van der Zouwen Eds. (1986), Sociocybernetic Paradoxes: Observation, Control and Evolution of Self-Steering Systems, Sage Publications Ltd, 248 pp.

- Pickering, Andrew. The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Further reading

- Laurent Dobuzinskis (1987), The New Cybernetics and the Science of Politics an Epistemological Analysis, Westview Press, pp. 223.

- Richard F. Ericson (1969). Organizational cybernetics and human values. Program of Policy Studies in Science and Technology. Monograph. George Washington University.

- Heinz von Foerster (1974), Cybernetics of Cybernetics, Urbana Illinois: University of Illinois. OCLC 245683481

- Heinz von Foerster (1981), 'Observing Systems", Intersystems Publications, Seaside, CA. OCLC 263576422

- Heinz von Foerster (2003), Understanding Understanding: Essays on Cybernetics and Cognition, New York : Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-95392-2

- Glanville, R. (1997). A ship without a rudder. In R. Glanville & G. de Zeeuw (Eds.), Problems of excavating cybernetics and systems. Southsea: BKS+.

- Glanville, R. (2002). Second order cybernetics. In F. Parra-Luna (Ed.), Systems science and cybernetics. In Encyclopaedia of life support systems (EOLSS). Oxford: EoLSS.

- Glanville, R. (2004). The purpose of second-order cybernetics. Kybernetes, 33(9/10), 1379-1386. doi: 10.1108/03684920410556016

- F. Heylighen, E. Rosseel & F. Demeyere Eds. (1990), Self-steering and Cognition in Complex Systems: Toward a New Cybernetics, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, New York, 432 pp.

- Joshua B. Mailman (2016), "Cybernetic Phenomenology of Music, Embodied Speculative Realism, and Aesthetics Driven Techné for Spontaneous Audio-visual Expression", in: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 5–95.

- Karl H. Müller (2008), The New Science of Cybernetics. The Evolution of Living Research Designs, vol. I: Methodology. Vienna:edition echoraum

- Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela (1988). "The Tree of Knowledge", Shambhala, Boston and London.

- Humberto Maturana and Bernhard Poerksen (2004), "From Being to Doing". Carl-Auer Verlag, Heidelberg.

- Gordon Pask (1996). Heinz von Foerster's Self-Organisation, the Progenitor of Conversation and Interaction Theories, Systems Research 13, 3, pp. 349–362

- Scott, B. (2001). Conversation Theory: a Dialogic, Constructivist Approach to Educational Technology, Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 8, 4, pp. 25–46.

- Sweeting, B. (2015). Cybernetics of practice. Kybernetes, 44(8/9), 1397-1405. doi: 10.1108/K-11-2014-0239

- Sweeting, B. (2016). Design Research as a Variety of Second-Order Cybernetic Practice. Constructivist Foundations, 11(3), 572-579. Reprinted in Alexander Riegler, Karl H Müller, Stuart A Umpleby (Eds) (2017), New Horizons for Second-Order Cybernetics: pp. 227-238.

- William Irwin Thompson (ed.), (1987), 'Gaia - a way of knowing". Lindisfarne Press, New York.

- Ralf-Eckhard Türke (2008), A second-order notion of Governance: Governance - Systemic Foundation and Framework (Contributions to Management Science, Physica of Springer, 2008) ISBN 978-3-7908-2079-9

- Stuart Umpleby (1989), "The science of cybernetics and the cybernetics of science", in: Cybernetics and Systems", Vol. 21, No. 1, (1990), pp. 109–121.

- Francisco Varela (1991), "The Embodied Mind", MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Francisco Varela, (1999), "Ethical Know-How", Stanford University Press.

External links

- The International Sociological Association (ISA) Research Committee 51 on Sociocybernetics (ISA-RC51)

- Heylighen, F.; Joslyn, C. (3 September 2001). "Second-Order Cybernetics". Principia Cybernetica Web. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018.

- Cybernetics and Second-Order Cybernetics

- New Order from Old: The Rise of Second-Order Cybernetics and Implications for Machine Intelligence

- Constructivist Foundations, an international peer-reviewed academic journal that focuses on constructivist approaches to science and philosophy, including radical constructivism, enactivism, second-order cybernetics, the theory of autopoiesis, and neurophenomenology.

- Heinz von Foerster's Self Organization

- Cybernetic Orders

- History of organizational events of the American Society of Cybernetics. In 1981 the title of the ASC conference was "The New Cybernetics", Oct. 29 – Nov. 1, GWU, Washington, DC (chair Larry Richards, local arrangements Stuart Umpleby).