Shōjo manga

Shōjo manga (少女漫画), also romanized as shojo or shoujo, are Japanese comics aimed at a young teen female target-demographic readership. The name romanizes the word 少女 (shōjo), literally meaning "young woman". Shōjo manga covers many subjects in a variety of narrative styles, from historical drama to science fiction, often with a focus on romantic relationships or emotions.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Anime and manga |

|---|

|

|

|

Strictly speaking, however, shōjo manga does not comprise a style or genre, but rather indicates a target demographic.[2][3]

History

Japanese magazines specifically for girls, known as shōjo magazines, first appeared in 1902 with the founding of Shōjo-kai (少女界, lit. "Girls' World") and continued with others such as Shōjo Sekai (少女世界, lit. "Girls' World") (1906) and the long-running Shōjo no Tomo (少女の友, lit. "Girls' Friend") (1908).[2][4]

The roots of the wide-eyed look commonly associated with shōjo manga date back to shōjo magazine illustrations during the early 20th century. The most important illustrators associated with this style at the time were Yumeji Takehisa and particularly Jun'ichi Nakahara, who, influenced by his work as a doll creator, frequently drew female characters with big eyes in the early 20th century. This had a significant influence on early shōjo manga, evident in the work of influential manga artists such as Macoto Takahashi and Riyoko Ikeda.[5]

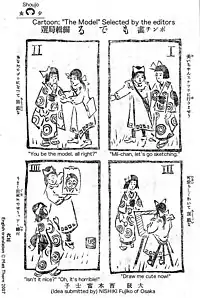

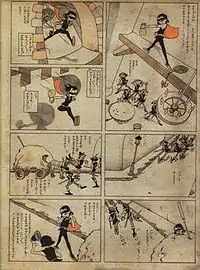

Simple, single-page manga began to appear in these magazines by 1910, and by the 1930s more sophisticated humor-strips had become an essential feature of most girls' magazines. The most popular manga, Katsuji Matsumoto's Kurukuru Kurumi-chan (くるくるクルミちゃん), debuted on the pages of Shōjo no Tomo in 1938.[6] As World War II progressed, however, "comics, perhaps regarded as frivolous, began to disappear".[7]

Postwar shōjo manga, such as Shosuke Kurakane's popular Anmitsu Hime (あんみつ姫, lit. "Princess Anmitsu"),[8] initially followed the pre-war pattern of simple humor-strips. But Osamu Tezuka's postwar revolution, introducing intense drama and serious themes to children's manga, spread quickly to shōjo manga, particularly after the enormous success of his seminal Princess Knight (リボンの騎士, Ribon no Kishi).[7]

Until the mid-1960s, men vastly outnumbered the women (for example: Toshiko Ueda, Hideko Mizuno, Masako Watanabe, and Miyako Maki) among the artists working on shōjo manga. Many male manga artists, such as Tetsuya Chiba,[9] functioned as rookies, waiting for an opportunity to move over to shōnen ("boys'") manga. Chiba asked his wife about girls' feelings for research for his manga. At this time, conventional job opportunities for Japanese women did not include becoming a manga artist.[10] Adapting Tezuka's dynamic style to shōjo manga (which had always been domestic in nature) proved challenging. According to Rachel Thorn:

While some chose to simply create longer humor-strips, others turned to popular girls' novels of the day as a model for melodramatic shōjo manga. These manga featured sweet, innocent pre-teen heroines, torn from the safety of family and tossed from one perilous circumstance to another, until finally rescued (usually by a kind, handsome young man) and re-united with their families.[11]

These early shōjo manga almost invariably had pre-adolescent girls as both heroines and readers. Unless they used a fantastic setting (as in Princess Knight) or a backdrop of a distant time or place, romantic love for the heroine remained essentially taboo. But the average age of the readership rose, and its interests changed. In the mid-1960s one of the few female artists in the field, Yoshiko Nishitani, began to draw stories featuring contemporary Japanese teenagers in love. This signaled a dramatic transformation of the genre.[12][13] This may have been due to the baby boomers becoming teens, and the industry trying to keep them as readers.[13]

Between 1950 and 1969, increasingly large audiences for manga emerged in Japan with the solidification of its two main marketing genres, shōnen manga aimed at adolescent boys and shōjo manga aimed at adolescent girls.[1][7] These romantic comedy shōjo manga were inspired by American TV dramas of the time.[14] The success of the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, and the gold medal won by the Japan women's national volleyball team, influenced a series of sports shōjo manga, such as Attack No. 1 (アタックNo.1, Atakku Nanbā Wan). On December 5, 1966, the first shōjo anime series, Sally the Witch (魔法使いサリー, Mahōtsukai Sarī), premiered in Japan on NET TV.[15] In May 1967, shōjo manga began being published in tankōbon format.[16]

Between roughly 1969 and 1971, a flood of young female manga artists transformed the genre again. Some, including Moto Hagio, Yumiko Ōshima, and Keiko Takemiya, became known as the Year 24 Group (24年組, Nijūyo-nen Gumi), or the Fabulous Year 24 Group (花の24年組, Hana no Nijūyo-nen Gumi), so named from the approximate year of birth many of them shared: Shōwa 24, or 1949. This loosely defined group experimented with content and form, inventing such subgenres such as shōnen-ai (lit. "boy love"), and earning the long-maligned shōjo manga unprecedented critical praise.[17] Other female artists of the same generation, such as Riyoko Ikeda, Yukari Ichijo, and Sumika Yamamoto, garnered unprecedented popular support with such hits (respectively) as The Rose of Versailles (ベルサイユのばら, Berusaiyu no Bara), Designer (デザイナー, Dezainaa), and Aim for the Ace! (エースをねらえ!, Ēsu o Nerae!).[1][2][12][13][7][18][19] During that era, women's roles in Japanese society were changing, and women were being elected to the National Diet, and publishers responded by employing more female talent.[13] Since the mid-1970s, women have created the vast majority of shōjo manga; notable exceptions include Mineo Maya and Shinji Wada.

From 1975, shōjo manga continued to develop stylistically while simultaneously branching out into different but overlapping subgenres.[20] Meiji University professor Yukari Fujimoto writes that during the 1990s, shōjo manga became concerned with self-fulfillment. She intimates that the Gulf War influenced the development of female characters "who fight to protect the destiny of a community", such as Red River, Basara, Magic Knight Rayearth, and Sailor Moon. Fujimoto opines that the shōjo manga of the 1990s depicted emotional bonds between women as stronger than the bonds between a man and a woman.[21] Major subgenres include romance, science fiction, fantasy, magical girls, yaoi, and "ladies' comics" (in Japanese, redisu レディース, redikomi レディコミ, and josei 女性).[22][23]

Meaning and spelling

As shōjo literally means "girl" in Japanese, the equivalent of the Western usage will generally include the term: girls' manga (少女漫画, shōjo manga), or anime for girls (少女向けアニメ shōjo-muke anime). The parallel terms shōnen, seinen, and josei also occur in the categorization of manga and anime, with similar qualification. Though the terminology originates with the Japanese publishers and advertisers,[24] cultural differences with the West mean that labeling in English tends to vary wildly, with the types often confused and misapplied.

Due to vagaries in the romanization of Japanese, publishers may transcribe 少女 (written しょうじょ in hiragana) in a wide variety of ways. By far the most common form, shoujo, follows English phonology, preserves the spelling, and requires only ASCII input. The Hepburn romanization shōjo uses a macron for the long vowel, though the prevalence of Latin-1 fonts often results in a circumflex instead, as in shôjo. Many English-language texts just ignore long vowels, using shojo, potentially leading to confusion with 処女 (shojo, lit. "virgin") as well as other possible meanings. Finally, transliterators may use Nihon-shiki-type mirroring of the kana spelling: syôjyo, or syoujyo.

Western adoption

Western fans classify a wide variety of titles as shōjo, even though their Japanese creators label them differently. Anything non-offensive and featuring female characters may classify as shōjo manga, such as the shōnen comedy series Azumanga Daioh.[25] Similarly, as romance has become a common element of many shōjo works, any title with romance – such as the shōnen series Love Hina[26] or the seinen series Oh My Goddess! – tend to get mislabeled.

This confusion also extends beyond the fan community; articles aimed at the mainstream also widely misrepresent the terms. In an introduction to anime and manga, British writer Jon Courtenay Grimwood writes: "Maison Ikkoku comes from Rumiko Takahashi, one of the best-known of all shôjo writers. Imagine a very Japanese equivalent of Sweet Valley High or Melrose Place. It has Takahashi's usual and highly successful mix of teenagers and romance, with darker clouds of adolescence hovering."[27] Takahashi is a famous shōnen manga artist, but Maison Ikkoku, one of her few seinen titles and serialized in Big Comic Spirits magazine, is aimed at males in their 20s.

Rachel Thorn, who has made a career out of studying girls' comics, attempts to clarify the matter by explaining that "shôjo manga are manga published in shôjo magazines (as defined by their publishers)".[3] However, English publishers and stores have problems retailing shōjo titles, including its spelling. Licensees such as Dark Horse Comics have misidentified several of the seinen titles, and in particular, manga and anime intended for a younger audience in Japan often contains violent or mature themes that would be targeted toward an older demographic in the US.[28] In this way licensees often either voluntarily censor titles or re-market them toward an older audience. In the less conservative European markets, content that might be heavily edited or cut in an English-language release often remains in French, German, and other translated editions.

As one effect of these variations, American companies have moved to use the borrowed words that have gained name-value in fan communities, but to separate them from the Japanese meaning. In their shōjo manga range, publisher Viz Media attempted a re-appropriation of the term, providing the following definition:

shô·jo (sho'jo) n. 1. Manga appealing to both female and male readers. 2. Exciting stories with true-to-life characters and the thrill of exotic locales. 3. Connecting the heart and mind through real human relationships.[29]

Manga and anime labeled as shōjo need not only interest girls; some titles gain a following outside the traditional audience. For instance, Frederik L. Schodt identifies Akimi Yoshida's Banana Fish as:

...one of the few girls' manga a red-blooded Japanese male adult could admit to reading without blushing. Yoshida, while adhering to the conventions of girls' comics in her emphasis on gay male love, made this possible by eschewing flowers and bug eyes in favor of tight bold strokes, action scenes, and speed lines.[23]

However, such successful "crossover" titles remain the exception rather than the rule: the archetypal shōjo manga magazine Hana to Yume has a 95% female readership, with a majority aged 17 or under.[30]

The growing popularity of romantic shōjo manga in North America encouraged Toronto-based publisher Harlequin, in agreement with Dark Horse Comics, to release manga-styled romantic comics starting in 2005. Harlequin's executive vice president Pam Laycok stated that the market has "vast potential".[31]

Circulation figures

The reported average circulations for some of the top-selling shōjo manga magazines in 2007 included:

| Title | Reported circulation | First published |

|---|---|---|

| Ciao | 982,834 | 1977 |

| Nakayoshi | 400,000 | 1954 |

| Ribon | 376,666 | 1955 |

| Bessatsu Margaret | 320,000 | 1964 |

| Hana to Yume | 226,826 | 1974 |

| Cookie | 200,000 | 1999 |

| Deluxe Margaret | 181,666 | 1967 |

| Margaret | 177,916 | 1963 |

| LaLa | 170,833 | 1976 |

| Cheese! | 144,750 | 1996 |

For comparison, circulations for the top-selling magazines in other categories for 2007 included:

| Category | Magazine Title | Reported Circulation |

|---|---|---|

| Top-selling shōnen manga magazine | Weekly Shōnen Jump | 2,778,750 |

| Top-selling seinen manga magazine | Young Magazine | 981,229 |

| Top-selling josei manga magazine | You | 194,791 |

| Top-selling non-manga magazine | Monthly the Television | 1,018,919 |

(Source for all circulation figures: Japan Magazine Publishers Association[32])

Shōjo magazines in Japan

In a strict sense, the term "shōjo manga" refers to a manga serialized in a shōjo manga magazine. The list below contains past and current Japanese shōjo manga magazines, grouped according to their publishers. Such magazines can appear on a variety of schedules, including bi-weekly (Margaret, Hana to Yume, Shōjo Comic), monthly (Ribon, Bessatsu Margaret, Bessatsu Friend, LaLa), bi-monthly (Deluxe Margaret, LaLa DX, The Dessert), and quarterly (Cookie Box, Unpoko).

Shueisha

- Ribon (monthly, 1955–present)

- Ribon Special (published 5 times a year, 1990)

- Ribon Original (bi-monthly, 1981–2006)

- Margaret (weekly, 1963–present)

- Bessatsu Margaret (monthly, 1964–present)

- Deluxe Margaret (bi-monthly, 1967–2010)

- The Margaret (bi-monthly, 1982–present)

- Bessatsu Margaret Sister (irregular, 2010–present)

- Bouquet (monthly, 1978–2000)

- Bouquet Deluxe or Bouquet DX (irregular, 1980–2000)

- Bouquet Selection (1983–1990) – terminated after publishing seven anthology and artist special issues

- Cookie (weekly, 2000–present)

- Cookie Box (quarterly, 2000–2009) – succeeded Bouquet Deluxe

Kodansha

- Nakayoshi (monthly, 1954–present)

- Aria (monthly, 2010–present)

- Shōjo Friend (1962–1996) – succeeded Shōjo Club

- Bessatsu Friend (1965–present)

- Dessert (1996–present)

- The Dessert (1999–present)

Shogakukan

- Ciao (1977–present)

- Ciao DX (2014–present)

- Ciao DX Horror & Mystery (2009–present)

- ChuChu

- Sho-Comi (1968–present, formerly Shōjo Comic)

- Betsucomi (1970–present, formerly Bessatsu Shōjo Comic)

- Deluxe Betsucomi

- Cheese! (1996–present)

- Premiere Cheese! (2016–present, formerly Cheese! Zōkan)

- Pochette

- Pyon Pyon (1988–1992)

- Pucchigumi (2006–present)

Hakusensha

- Hana to Yume (1974–present)

- Bessatsu Hana to Yume (1977–present)

- LaLa (1976–present)

- LaLa DX

- Melody

Akita Shoten

- Princess

- Princess Gold (1979–2020)

- Petit Princess (transitioned to digital only in 2016)

- Bonita (1981–1995)

- Mystery Bonita (1988–present)

- Susperia Mystery

- Renai Max

- Hitomi (1978–1991)

Kadokawa Shoten

- Asuka (1985–present)

- Monthly Comic Gene (2011–present)

Web magazine

- Manga Airport

- Digital Margaret, also known as Digima!

- &Flower

- Mobile Flower, also known as Mobafura

Shinshokan

- Unpoko

Outside Japan

- Shojo Beat (2005–2009), published in North America by Viz Media

- Wink, published in Korea

See also

- Bishōjo (lit. "beautiful girl") – descriptive of the character type rather than the audience

- Class S – historical homoerotic genre about passionate friendships between girls for a female audience

- History of manga

- Josei manga – intended for adult women

- List of shōjo manga magazines

- Magical girl – a genre featuring girls with magical powers or who use magic, initially aimed at a young female audience

- Otome game – story-based video games targeted towards women, often romantic in nature

- Seinen manga – intended for adult men

- Shōnen manga – intended for boys

- Shoujocon – an anime convention held annually from 2000 to 2003

- Sunjung manhwa – Korean shōjo-style comics

- Yaoi – homoerotic stories about men in love for girls and women

- Yuri (genre) – homoerotic stories about women in love for either gender based on publication

Notes

- Toku, Masami, ed. (2005). "Shojo Manga: Girl Power!". Chico Statements Magazine. California State University, Chico. ISBN 1-886226-10-5. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011.

- Thorn, Rachel (2001). "Shôjo Manga – Something for the Girls". The Japan Quarterly. Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun. 48 (3). Archived from the original on February 19, 2007.

- Thorn, Rachel (2004). "What Shôjo Manga Are and Are Not: A Quick Guide for the Confused". Matt-Thorn.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015.

- 明治~昭和 少女雑誌のご紹介 [Meiji – Shōwa: An Introduction to Girls' Magazines]. Kikuyō Town Library. Kikuyō, Kumamoto, Japan. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019.

- Masuda, Nozomi (June 5, 2015). "Shojo Manga and its Acceptance: What is the Power of Shojo Manga?". In Toku, Masami (ed.). International Perspectives on Shojo and Shojo Manga: The Influence of Girl Culture. New York: Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-138-80948-2.

- Thorn, Rachel. "Pre-World War II Shôjo Manga and Illustrations". Matt-Thorn.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (January 25, 2013) [First published in 1983]. Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. New York: Kodansha USA. ISBN 978-1-56836-476-6.

- Yonezawa, Yoshihiro, ed. (1991). Kodomo no Shōwa-shi: Shōjo Manga no Sekai I, Shōwa 20 nen – 37 nen 子供の昭和史──少女マンガの世界 I 昭和20年〜37年 [A Children's History of Showa-Era Japan: The World of Shōjo Manga I, 1945–1962]. Bessatsu Taiyō (in Japanese). Tokyo: Heibonsha. ISBN 978-4-582-94239-2.

- Thorn, Rachel (2005). "The Moto Hagio Interview". The Comics Journal. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books (269). Archived from the original on January 13, 2016.

- Toku, Masami (2007). "Shojo Manga! Girls' Comics! A Mirror of Girls' Dreams". Mechademia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2: 22–23. doi:10.1353/mec.0.0013. ISSN 1934-2489. S2CID 120302321.

- Thorn, Rachel. "The Multi-Faceted Universe of Shōjo Manga". Matt-Thorn.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Yonezawa, Yoshihiro, ed. (1991). Kodomo no Shōwa-shi: Shōjo Manga no Sekai II, Shōwa 38 nen – 64 nen 子供の昭和史──少女マンガの世界 II 昭和38年〜64年 [A Children's History of Showa-Era Japan: The World of Shōjo Manga II, 1963–1989]. Bessatsu Taiyō (in Japanese). Tokyo: Heibonsha. ISBN 978-4-582-94240-8.

- Thorn, Rachel (2005). "The Magnificent Forty-Niners". The Comics Journal. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books (269). Archived from the original on November 2, 2019.

- Saito, Kumiko (2011). "Desire in Subtext: Gender, Fandom, and Women's Male-Male Homoerotic Parodies in Contemporary Japan". Mechademia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 6: 173. doi:10.1353/mec.2011.0000. ISSN 1934-2489. S2CID 144768939.

- Duffield, Patricia (October 2000). "Witches in Anime". Animerica Extra. Vol. 3 no. 11. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019.

- Kálovics, Dalma (2016). "The missing link of shōjo manga history: the changes in 60s shōjo manga as seen through the magazine Shūkan Margaret" (PDF). Kyōto Seika Daigaku Kiyō. Kyoto Seika University (49). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2019.

- Anan, Nobuko (2016). Contemporary Japanese Women's Theatre and Visual Arts: Performing Girls' Aesthetics. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137372987. ISBN 978-1-349-55706-6.

- Gravett, Paul (July 19, 2004). Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. New York: Harper Design. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-1-85669-391-2.

- Lent, 2001, op. cit., pp. 9–10.

- Ogi, Fusami (2003). "Female Subjectivity and Shoujo (Girls) Manga (Japanese Comics): Shoujo in Ladies' Comics and Young Ladies' Comics" (PDF). The Journal of Popular Culture. Blackwell Publishing. 36 (4): 780–803. doi:10.1111/1540-5931.00045. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2019.

- Fujimoto, Yukari (2008). "Japanese Contemporary Manga (Number 1): Shōjo (Girls Manga)" (PDF). Japanese Book News. Vol. 56. The Japan Foundation. p. 12. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Gravett, Paul (July 19, 2004). Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. New York: Harper Design. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-85669-391-2.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-23-5.

- 雑誌ジャンルおよびカテゴリ区分一覧 [Magazine genre and category list] (PDF) (in Japanese). Japan Magazine Publishers Association. February 15, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2019.

- Goetz, Melanie (August 19, 2004). "MIT Anime Showings: Synopses - Azumanga Daioh". MIT Anime Club. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008.

- Chobot, Jessica (December 13, 2005). "Shojo Showdown: Making sense of the manga genres". IGN. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019.

- Grimwood, Jon Courtenay (2006). "Every Picture...". Books Quarterly (19): 42.

- "Shojo Update: Your Comments and Our Answers". ICv2. August 22, 2001. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019.

- Nasu, Yukie (November 8, 2004). Here Is Greenwood. 1. San Francisco, California: Viz Media. ISBN 978-1-59116-604-7.

- "Hana to Yume Readers Data" (PDF) (in Japanese). Japan Magazine Publishers Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 24, 2010.

- "Dark Horse to Publish Harlequin Manga". Anime News Network (Press release). June 1, 2005. Archived from the original on December 8, 2018.

- 「マガジンデータ2007」発行のご案内 [Information for Magazine Data 2007] (in Japanese). Japan Magazine Publishers Association. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) Note: The publication, which relies on information provided by publishers, categorizes the magazine Cookie as josei, but Shueisha's s-manga.net website clearly categorizes that magazine as shōjo, hence its categorization here.

References

- Ultimate Manga Guide (zip), version 13.6, last modified July 31, 2004

- Shōjo Anime List, last modified February 14, 1995

- Napier, Susan J. (2001). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23862-9.

- Thorn, Rachel (2001). "Shôjo Manga – Something for the Girls". The Japan Quarterly. Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun. 48 (3). Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- Garrity, Shaenon K. (2008). "The Boys of Shojo Manga". ComiXology. Archived from the original on August 24, 2009.

- Shamoon, Deborah (2007). "Revolutionary Romance: The Rose of Versailles and the Transformation of Shojo Manga". Mechademia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2: 3–17. doi:10.1353/mec.0.0009. S2CID 121163032.

- Takahashi, Mizuki (2008). "Opening the Closed World of Shojo Manga". In MacWilliams, Mark W. (ed.). Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1601-2. Archived from the original on January 3, 2011.

Further reading

- Ogi, Fusami (2001). "Beyond Shoujo, Blending Gender: Subverting the Homogendered World in Shoujo Manga (Japanese Comics for Girls)". International Journal of Comic Art. 3 (2): 151–161.

- Prough, Jennifer S. (2011). Straight from the Heart: Gender, Intimacy, and the Cultural Production of Shōjo Manga. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3528-6.

- Saito, Kumiko (2014). "Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenges of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society". The Journal of Asian Studies. 73 (1): 143–164. doi:10.1017/S0021911813001708. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 43553398.

- Toku, Masami, ed. (2015). International Perspectives on Shojo and Shojo Manga: The Influence of Girl Culture. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-80948-2.