Slavery in ancient Rome

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Besides manual labor, slaves performed many domestic services, and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Accountants and physicians were often slaves. Slaves of Greek origin in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those sentenced to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Slaves were considered property under Roman law and had no legal personhood. Most slaves would never be freed. Unlike Roman citizens, they could be subjected to corporal punishment, sexual exploitation (prostitutes were often slaves), torture and summary execution. Over time, however, slaves gained increased legal protection, including the right to file complaints against their masters.

One major source of slaves had been Roman military expansion during the Republic. The use of former enemy soldiers as slaves led perhaps inevitably to a series of en masse armed rebellions, the Servile Wars, the last of which was led by Spartacus. During the Pax Romana of the early Roman Empire (1st–2nd centuries AD), emphasis was placed on maintaining stability, and the lack of new territorial conquests dried up this supply line of human trafficking. To maintain an enslaved work force, increased legal restrictions on freeing slaves were put into place. Escaped slaves would be hunted down and returned (often for a reward). There were also many cases of poor people selling their children to richer neighbors as slaves in times of hardship.

Origins

In his Institutiones (161 AD), the Roman jurist Gaius wrote that:

[Slavery is] the state that is recognized by the ius gentium in which someone is subject to the dominion of another person contrary to nature.

— Gaius, Institutiones 1.3.2[2]

The 1st century BC Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus indicates that the Roman institution of slavery began with the legendary founder Romulus giving Roman fathers the right to sell their own children into slavery, and kept growing with the expansion of the Roman state. Slave ownership was most widespread throughout the Roman citizenry from the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) to the 4th century AD. The Greek geographer Strabo (1st century AD) records how an enormous slave trade resulted from the collapse of the Seleucid Empire (100–63 BC).[3]

The Twelve Tables, Rome's oldest legal code, has brief references to slavery, indicating that the institution was of long standing. In the tripartite division of law by the jurist Ulpian (2nd century AD), slavery was an aspect of the ius gentium, the customary international law held in common among all peoples (gentes). The "law of nations" was neither considered natural law, thought to exist in nature and govern animals as well as humans, nor civil law, belonging to the emerging bodies of laws specific to a people in Western societies.[4] All human beings are born free (liberi) under natural law, but slavery was held to be a practice common to all nations, who might then have specific civil laws pertaining to slaves.[4] In ancient warfare, the victor had the right under the ius gentium to enslave a defeated population; however, if a settlement had been reached through diplomatic negotiations or formal surrender, the people were by custom to be spared violence and enslavement. The ius gentium was not a legal code,[5] and any force it had depended on "reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct."[6]

Vernae (singular verna) were slaves born within a household (familia) or on a family farm or agricultural estate (villa). There was a stronger social obligation to care for vernae, whose epitaphs sometimes identify them as such, and at times they would have been the children of free males of the household.[7][8] The general Latin word for slave was servus.

Slavery and warfare

Throughout the Roman period many slaves for the Roman market were acquired through warfare. Many captives were either brought back as war booty or sold to traders,[9] and ancient sources cite anywhere from hundreds to tens of thousands of such slaves captured in each war.[10][11] These wars included every major war of conquest from the Monarchical period to the Imperial period, as well as the Social and Samnite Wars.[12] The prisoners taken or retaken after the three Roman Servile Wars (135–132, 104–100, and 73–71 BC, respectively) also contributed to the slave supply.[13] While warfare during the Republic provided the largest figures for captives,[14] warfare continued to produce slaves for Rome throughout the imperial period.[15]

Piracy has a long history of adding to the slave trade,[16] and the period of the Roman Republic was no different. Piracy was particularly lucrative in Cilicia where pirates operated with impunity from a number of strongholds. Pompey was credited with effectively eradicating piracy from the Mediterranean in 67 BC.[17] Although large-scale piracy was curbed under Pompey and controlled under the Roman Empire, it remained a steady institution, and kidnapping through piracy continued to contribute to the Roman slave supply. Augustine lamented the wide-scale practice of kidnapping in North Africa in the early 5th century AD.[18]

Trade and economy

During the period of Roman imperial expansion, the increase in wealth amongst the Roman elite and the substantial growth of slavery transformed the economy.[19] Although the economy was dependent on slavery, Rome was not the most slave-dependent culture in history. Among the Spartans, for instance, the slave class of helots outnumbered the free by about seven to one, according to Herodotus.[20] In any case, the overall role of slavery in Roman economy is a discussed issue among scholars.[21][22][23]

Delos in the eastern Mediterranean was made a free port in 166 BC and became one of the main market venues for slaves. Multitudes of slaves who found their way to Italy were purchased by wealthy landowners in need of large numbers of slaves to labor on their estates. Historian Keith Hopkins noted that it was land investment and agricultural production which generated great wealth in Italy, and considered that Rome's military conquests and the subsequent introduction of vast wealth and slaves into Italy had effects comparable to widespread and rapid technological innovations.[3]

Augustus imposed a 2 percent tax on the sale of slaves, estimated to generate annual revenues of about 5 million sesterces—a figure that indicates some 250,000 sales.[24] The tax was increased to 4 percent by 43 AD.[25] Slave markets seem to have existed in every city of the Empire, but outside Rome the major center was Ephesus.[24]

Demography

Estimates for the prevalence of slavery in the Roman Empire vary. Estimates of the percentage of the population of Italy who were slaves range from 30 to 40 percent in the 1st century BC, upwards of two to three million slaves in Italy by the end of the 1st century BC, about 35% to 40% of Italy's population.[26][27][28] For the empire as a whole during the period 260–425 AD, according to a study done by Kyle Harper, the slave population has been estimated at just under five million, representing 10–15% of the total population of 50–60 million+ inhabitants. An estimated 49% of all slaves were owned by the elite, who made up less than 1.5% of the empire's population. About half of all slaves worked in the countryside where they were a small percentage of the population except on some large agricultural, especially imperial, estates; the remainder of the other half were a significant percentage — 25% or more — in towns and cities as domestics and workers in commercial enterprises and manufacturers.[29]

Roman slavery was not based on ideas of race.[30][31] Slaves were drawn from all over Europe and the Mediterranean, including Gaul, Hispania, North Africa, Syria, Germany, Britannia, the Balkans, Greece, etc. Those from outside of Europe were predominantly of Greek descent, while the Jewish ones never fully assimilated into Roman society, remaining an identifiable minority. The slaves (especially the foreigners) had higher mortality rates and lower birth rates than natives, and were sometimes even subjected to mass expulsions.[32] The average recorded age at death for the slaves of the city of Rome was extraordinarily low: seventeen and a half years (17.2 for males; 17.9 for females).[33] By comparison, life expectancy at birth for the population as a whole was in the mid-twenties (36% percent of men and 27% of women could expect to reach the age of 62 if they succeeded in reaching the age of 10).

The overall impact of slavery on the Italian genetics was insignificant though, because the slaves imported in Italy were native Europeans, mostly from Germanic and Slavic tribes and very few if any of them had non-European origin. This has been further confirmed by recent biochemical analysis of 166 skeletons from three non-elite imperial-era cemeteries in the vicinity of Rome (where the bulk of the slaves lived), which shows that only one individual definitely came from outside of Europe (North Africa), and another two possibly did, but results are inconclusive. In the rest of the Italian peninsula, the fraction of non-European slaves was definitively much lower than that.[34][35]

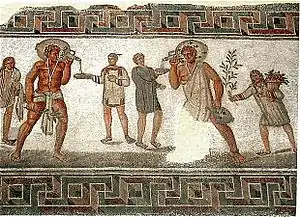

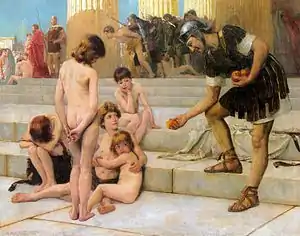

Auctions and sales

New slaves were primarily acquired by wholesale dealers who followed the Roman armies.[36] Many people who bought slaves wanted strong slaves, mostly men.[37] Child slaves cost less than adults[38] although other sources state their price as higher.[39] Julius Caesar once sold the entire population of a conquered region in Gaul, no fewer than 53,000 people, to slave dealers on the spot.[40]

Within the empire, slaves were sold at public auction or sometimes in shops, or by private sale in the case of more valuable slaves. Slave dealing was overseen by the Roman fiscal officials called quaestors.

Sometimes slaves stood on revolving stands, and around each slave for sale hung a type of plaque describing their origin, health, character, intelligence, education, and other information pertinent to purchasers. Prices varied with age and quality, with the most valuable slaves fetching high prices. Because the Romans wanted to know exactly what they were buying, slaves were presented naked. The dealer was required to take a slave back within six months if the slave had defects that were not manifest at the sale, or make good the buyer's loss.[41] Slaves to be sold with no guarantee were made to wear a cap at the auction.

Debt slavery

Nexum was a debt bondage contract in the early Roman Republic. Within the Roman legal system, it was a form of mancipatio. Though the terms of the contract would vary, essentially a free man pledged himself as a bond slave (nexus) as surety for a loan. He might also hand over his son as collateral. Although the bondsman could expect to face humiliation and some abuse, as a legal citizen he was supposed to be exempt from corporal punishment. Nexum was abolished by the Lex Poetelia Papiria in 326 BC, in part to prevent abuses to the physical integrity of citizens who had fallen into debt bondage.

Roman historians illuminated the abolition of nexum with a traditional story that varied in its particulars; basically, a nexus who was a handsome but upstanding youth suffered sexual harassment by the holder of the debt. In one version, the youth had gone into debt to pay for his father's funeral; in others, he had been handed over by his father. In all versions, he is presented as a model of virtue. Historical or not, the cautionary tale highlighted the incongruities of subjecting one free citizen to another's use, and the legal response was aimed at establishing the citizen's right to liberty (libertas), as distinguished from the slave or social outcast (infamis).[42]

Cicero considered the abolition of nexum primarily a political maneuver to appease the common people (plebs): the law was passed during the Conflict of the Orders, when plebeians were struggling to establish their rights in relation to the hereditary privileges of the patricians. Although nexum was abolished as a way to secure a loan, debt bondage might still result after a debtor defaulted.[43]

Types of work

Slaves worked in a wide range of occupations that can be roughly divided into five categories: household or domestic, imperial or public, urban crafts and services, agriculture, and mining.[44]

Epitaphs record at least 55 different jobs a household slave might have,[44] including barber, butler, cook, hairdresser, handmaid (ancilla), wash their master's clothes, wet nurse or nursery attendant, teacher, secretary, seamstress, accountant, and physician.[3] A large elite household (a domus in town, or a villa in the countryside) might be supported by a staff of hundreds.[44] The living conditions of slaves attached to a domus (the familia urbana), while inferior to those of the free persons they lived with, were sometimes superior to that of many free urban poor in Rome.[45] Household slaves likely enjoyed the highest standard of living among Roman slaves, next to publicly owned slaves, who were not subject to the whims of a single master.[41] Imperial slaves were those attached to the emperor's household, the familia Caesaris.[44]

In urban workplaces, the occupations of slaves included fullers, engravers, shoemakers, bakers, mule drivers, and prostitutes. Farm slaves (familia rustica) probably lived in more healthful conditions. Roman agricultural writers expect that the workforce of a farm will be mostly slaves, managed by a vilicus, who was often a slave himself.[44]

Slaves numbering in the tens of thousands were condemned to work in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal.[44] Damnati in metallum ("those condemned to the mine") were convicts who lost their freedom as citizens (libertas), forfeited their property (bona) to the state, and became servi poenae, slaves as a legal penalty. Their status under the law was different from that of other slaves; they could not buy their freedom, be sold, or be set free. They were expected to live and die in the mines.[47] Imperial slaves and freedmen (the familia Caesaris) worked in mine administration and management.[48]

In the Late Republic, about half the gladiators who fought in Roman arenas were slaves, though the most skilled were often free volunteers.[49] Successful gladiators were occasionally rewarded with freedom. However gladiators, being trained warriors and having access to weapons, were potentially the most dangerous slaves. At an earlier time, many gladiators had been soldiers taken captive in war. Spartacus, who was a rebel gladiator, led the great slave rebellion of 73–71 BC.

Servus publicus

A servus publicus was a slave owned not by a private individual, but by the Roman people. Public slaves worked in temples and other public buildings both in Rome and in the municipalities. Most performed general, basic tasks as servants to the College of Pontiffs, magistrates, and other officials. Some well-qualified public slaves did skilled office work such as accounting and secretarial services. They were permitted to earn money for their personal use.[50]

Because they had an opportunity to prove their merit, they could acquire a reputation and influence, and were sometimes deemed eligible for manumission. During the Republic, a public slave could be freed by a magistrate's declaration, with the prior authorization of the senate; in the Imperial era, liberty would be granted by the emperor. Municipal public slaves could be freed by the municipal council.[50]

Treatment and legal status

According to Marcel Mauss, in Roman times the persona gradually became "synonymous with the true nature of the individual" but "the slave was excluded from it. servus non habet personam ('a slave has no persona'). He has no personality. He does not own his body; he has no ancestors, no name, no cognomen, no goods of his own."[51] The testimony of a slave could not be accepted in a court of law[52] unless the slave was tortured—a practice based on the belief that slaves in a position to be privy to their masters' affairs would be too virtuously loyal to reveal damaging evidence unless coerced.

Rome differed from Greek city-states in allowing freed slaves to become citizens. After manumission, a male slave who had belonged to a Roman citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote.[53] A slave who had acquired libertas was thus a libertus ("freed person", feminine liberta) in relation to his former master, who then became his patron (patronus). As a social class, freed slaves were libertini, though later writers used the terms libertus and libertinus interchangeably.[54][55] Libertini were not entitled to hold public office or state priesthoods, nor could they achieve senatorial rank. During the early Empire, however, freedmen held key positions in the government bureaucracy, so much so that Hadrian limited their participation by law.[56] Any future children of a freedman would be born free, with full rights of citizenship.

Although in general freed slaves could become citizens, with the right to vote if they were male, those categorized as dediticii suffered permanent disbarment from citizenship. The dediticii were mainly slaves whose masters had felt compelled to punish them for serious misconduct by placing them in chains, branding them, torturing them to confess a crime, imprisoning them or sending them involuntarily to a gladiatorial school (ludus), or condemning them to fight with gladiator or wild beasts (their subsequent status was obviously a concern only to those who survived). Dediticii were regarded as a threat to society, regardless of whether their master's punishments had been justified, and if they came within a hundred miles of Rome, they were subject to reenslavement.[57]

Roman slaves could hold property which, despite the fact that it belonged to their masters, they were allowed to use as if it were their own.[58] Skilled or educated slaves were allowed to earn their own money, and might hope to save enough to buy their freedom.[59][60] Such slaves were often freed by the terms of their master's will, or for services rendered. A notable example of a high-status slave was Tiro, the secretary of Cicero. Tiro was freed before his master's death, and was successful enough to retire on his own country estate, where he died at the age of 99.[61][62][63] However, the master could arrange that slaves would only have enough money to buy their freedom when they were too old to work. They could then use the money to buy a new young slave while the old slave, unable to work, would be forced to rely on charity to stay alive.[64]

Several emperors began to grant more rights to slaves as the empire grew. Claudius announced that if a slave was abandoned by his master, he became free. Nero granted slaves the right to complain against their masters in a court. And under Antoninus Pius, a master who killed a slave without just cause could be tried for homicide.[65] Legal protection of slaves continued to grow as the empire expanded. It became common throughout the mid to late 2nd century AD to allow slaves to complain of cruel or unfair treatment by their owners.[66] Attitudes changed in part because of the influence among the educated elite of the Stoics, whose egalitarian views of humanity extended to slaves.

There are reports of abuse of slaves by Romans, but there is little information to indicate how widespread such harsh treatment was. Cato the Elder was recorded as expelling his old or sick slaves from his house. Seneca held the view that a slave who was treated well would perform a better job than a poorly treated slave. As most slaves in the Roman world could easily blend into the population if they escaped, it was normal for the masters to discourage slaves from running away by putting a tattoo reading "Stop me! I am a runaway!" or "tax paid" if the slaves were owned by the Roman state on the foreheads of their slaves.[67] For this reason, slaves usually wore headbands to cover up their disfiguring tattoos and at the Temple of Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, in Ephesus, archeologists have found thousands of tablets from escaped slaves asking Asclepius to make their tattoos on their foreheads disappear.[68] Crucifixion was the capital punishment meted out specifically to slaves, traitors, and bandits.[69][70][71][72] Marcus Crassus was supposed to have concluded his victory over Spartacus in the Third Servile War by crucifying 6,000 of the slave rebels along the Appian Way.

Rebellions and runaways

Moses Finley remarked, "fugitive slaves are almost an obsession in the sources". Rome forbade the harbouring of fugitive slaves, and professional slave-catchers were hired to hunt down runaways. Advertisements were posted with precise descriptions of escaped slaves, and offered rewards.[73] If caught, fugitives could be punished by being whipped, burnt with iron, or killed. Those who lived were branded on the forehead with the letters FUG, for fugitivus. Sometimes slaves had a metal collar riveted around the neck. One such collar is preserved at Rome and states in Latin, "I have run away. Catch me. If you take me back to my master Zoninus, you'll be rewarded."[41]

There was a constant danger of servile insurrection, which had more than once seriously threatened the republic.[74] The 1st century BC Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that slaves sometimes banded together to plot revolts. He chronicled the three major slave rebellions: in 135–132 BC (the First Servile War), in 104–100 BC (the Second Servile War), and in 73–71 BC (the Third Servile War).[75]

Serfdom

In addition to slavery, the Romans also practiced serfdom. By the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire faced a labour shortage. Large Roman landowners increasingly relied on Roman freemen, acting as tenant farmers, instead of slaves to provide labour.[76] The status of these tenant farmers, eventually known as coloni, steadily eroded. Because the tax system implemented by Diocletian assessed taxes based on both land and the inhabitants of that land, it became administratively inconvenient for peasants to leave the land where they were counted in the census.[76] In 332 AD Emperor Constantine issued legislation that greatly restricted the rights of the coloni and tied them to the land. Some see these laws as the beginning of medieval serfdom in Europe.

Slavery in philosophy and religion

Classical Roman religion

The religious holiday most famously celebrated by slaves at Rome was the Saturnalia, a December festival of role reversals during which time slaves enjoyed a rich banquet, gambling, free speech and other forms of license not normally available to them. To mark their temporary freedom, they wore the pilleus, the cap of freedom, as did free citizens, who normally went about bareheaded.[77][78] Some ancient sources suggest that master and slave dined together,[79][80] while others indicate that the slaves feasted first, or that the masters actually served the food. The practice may have varied over time.[81] Macrobius (5th century AD) describes the occasion thus:

Meanwhile the head of the slave household, whose responsibility it was to offer sacrifice to the Penates, to manage the provisions and to direct the activities of the domestic servants, came to tell his master that the household had feasted according to the annual ritual custom. For at this festival, in houses that keep to proper religious usage, they first of all honor the slaves with a dinner prepared as if for the master; and only afterwards is the table set again for the head of the household. So, then, the chief slave came in to announce the time of dinner and to summon the masters to the table.[82][83]

Saturnalian license also permitted slaves to enjoy a pretense of disrespect for their masters, and exempted them from punishment. The Augustan poet Horace calls their freedom of speech "December liberty" (libertas Decembri).[84][85] In two satires set during the Saturnalia, Horace portrays a slave as offering sharp criticism to his master.[86][87][88] But everyone knew that the leveling of the social hierarchy was temporary and had limits; no social norms were ultimately threatened, because the holiday would end.[89]

Another slaves' holiday (servorum dies festus) was held August 13[90] in honor of Servius Tullius, the legendary sixth king of Rome who was the child of a slave woman. Like the Saturnalia, the holiday involved a role reversal: the matron of the household washed the heads of her slaves, as well as her own.[91][92]

The temple of Feronia at Terracina in Latium was the site of special ceremonies pertaining to manumission. The goddess was identified with Libertas, the personification of liberty,[93] and was a tutelary goddess of freedmen (dea libertorum). A stone at her temple was inscribed "let deserving slaves sit down so that they may stand up free."[94][95]

Female slaves and religion

At the Matralia, a women's festival held June 11 in connection with the goddess Mater Matuta, free women ceremonially beat a slave girl and drove her from the community. Slave women were otherwise forbidden participation.[96]

Slave women were honored at the Ancillarum Feriae on July 7.[97][98] The holiday is explained as commemorating the service rendered to Rome by a group of ancillae (female slaves or "handmaids") during the war with the Fidenates in the late 4th century BC.[99][100] Weakened by the Gallic sack of Rome in 390 BC, the Romans next had suffered a stinging defeat by the Fidenates, who demanded that they hand over their wives and virgin daughters as hostages to secure a peace. A handmaid named either Philotis or Tutula came up with a plan to deceive the enemy: the ancillae would put on the apparel of the free women, spend one night in the enemy camp, and send a signal to the Romans about the most advantageous time to launch a counterattack.[96][101] Although the historicity of the underlying tale may be doubtful, it indicates that the Romans thought they had already had a significant slave population before the Punic Wars.[102]

Mystery cults

The Mithraic mysteries were open to slaves and freedmen, and at some cult sites most or all votive offerings are made by slaves, sometimes for the sake of their masters' wellbeing.[103] The cult of Mithras, which valued submission to authority and promotion through a hierarchy, was in harmony with the structure of Roman society, and thus the participation of slaves posed no threat to social order.[104]

Stoic philosophy

The Stoics taught that all men were manifestations of the same universal spirit, and thus by nature equal. Stoicism also held that external circumstances (such as being enslaved) did not truly impede a person from practicing the Stoic ideal of inner self-mastery: It has been said that one of the more important Roman stoics, Epictetus, spent his youth as a slave.

Early Christianity

Both the Stoics and some early Christians opposed the ill treatment of slaves, rather than slavery itself. Advocates of these philosophies saw them as ways to live within human societies as they were, rather than to overthrow entrenched institutions. In the Christian scriptures, equal pay and fair treatment of slaves was enjoined upon slave masters, and slaves were advised to obey their earthly masters, even if their masters are unfair, and lawfully obtain freedom if possible.[105][106][107][108]

Certain senior Christian leaders (such as Gregory of Nyssa and John Chrysostom) called for good treatment for slaves and condemned slavery, while others supported it. Christianity gave slaves an equal place within the religion, allowing them to participate in the liturgy. According to tradition, Pope Clement I (term c. 92–99), Pope Pius I (158–167) and Pope Callixtus I (c. 217–222) were former slaves.[109]

In literature

Although ancient authors rarely discussed slavery in terms of morals, because their society did not view slavery as the moral dilemma we do today,[110] they included slaves and the treatment of slaves in works in order to shed light on other topics—history, economy, an individual's character—or to entertain and amuse. Texts mentioning slaves include histories, personal letters, dramas, and satires, including Petronius' Banquet of Trimalchio, in which the eponymous freedman asserts "Slaves too are men. The milk they have drunk is just the same even if an evil fate has oppressed them."[111] Many literary works may have served to help educated Roman slave owners navigate acceptability in the master-slave relationships in terms of slaves' behavior and punishment. To achieve this navigation of acceptability, works often focus on extreme cases, such as the crucifixion of hundreds of slaves for the murder of their master. We must be careful to recognize these instances as exceptional and yet recognize that the underlying problems must have concerned the authors and audiences.[112] Examining the literary sources that mention ancient slavery can reveal both the context for and contemporary views of the institution. The following examples provide a sampling of different genres and portrayals.

Plutarch

Plutarch mentioned slavery in his biographical history in order to pass judgement on men's characters. In his Life of Cato the Elder, Plutarch revealed contrasting views of slaves. He wrote that Cato, known for his stringency, would resell his old servants because "no useless servants were fed in his house," but that he himself believes that "it marks an over-rigid temper for a man to take the work out of his servants as out of brute beasts."[113]

Cicero

A prolific letter writer, Cicero even wrote letters to one of his administrative slaves, one Marcus Tullius Tiro. Even though Cicero himself remarked that he only wrote to Tiro "for the sake of keeping to [his] established practice,"[114] he occasionally revealed personal care and concern for his slave. Indeed, just the fact that Tiro had enough education and freedom to express his opinions in letters to his master is exceptional and only allowed through his unique circumstances.[115] First, as an administrative slave, Tiro would have enjoyed better living and working conditions than the majority of slaves working in the fields, mines, or workhouses. Also, Cicero was an exceptional owner, even taking Tiro's education into his own hands.[116] While these letters suggest a familiarity and connection between master and slave, each letter still contains a direct command, suggesting that Cicero calculatingly used familiarity in order to ensure performance and loyalty from Tiro.[117]

Roman comedies

In Roman comedy, servi or slaves make up the majority of the stock characters, and generally fall into two basic categories: loyal slaves and tricksters. Loyal slaves often help their master in their plan to woo or obtain a lover (the most popular plot-driving element in Roman comedy). They are often dim, timid, and worried about what punishments may befall them. Trickster slaves are more numerous and often use their masters' unfortunate situation to create a "topsy-turvy" world in which they are the masters and their masters are subservient to them. The master will often ask the slave for a favor and the slave only complies once the master has made it clear that the slave is in charge, beseeching him and calling him lord, sometimes even a god.[118] These slaves are threatened with numerous punishments for their treachery, but always escape the fulfillment of these threats through their wit.[118]

Depictions of slaves in Roman comedies can be seen in the work of Plautus and Publius Terentius Afer. Dartmouth associate professor Roberta Stewart has stated that Plautus’ plays represent slavery "as a complex institution that raised perplexing problems in human relationships involving masters and slaves.”[119] Terence added a new element to how slaves were portrayed in his plays, due to his personal background as a former slave. In the work Andria, slaves are at the centerpiece off the plot. In this play, Simo, a wealthy Athenian wants his son, Pamphilius, to marry one girl but Pamphilius has his sights set on another. Much of the conflict in this play revolves around schemes with Pamphilius's slave, Davos, and the rest of the characters in the story. Many times throughout the play, slaves are allowed to engage in activity, such as the inner and personal lives of their owners, that wouldn't normally be seen with slaves in every day society. This is a form of satire by Terence due to the unrealistic nature of events that occurs between slaves and citizens in his plays.[120]

Emancipation

Freeing a slave was called manumissio, which literally means "sending out from the hand". The freeing of the slave was a public ceremony, performed before some sort of public official, usually a judge. The owner touched the slave on the head with a staff and he was free to go. Simpler methods were sometimes used, usually with the owner proclaiming a slave's freedom in front of friends and family, or just a simple invitation to recline with the family at dinner.

A felt cap called the Pileus was given to the former slave as symbol of manumission.

Slaves were freed for a variety of reasons; for a particularly good deed toward the slave's owner, or out of friendship or respect. Sometimes, a slave who had enough money could buy his freedom and the freedom of a fellow slave, frequently a spouse. However, few slaves had enough money to do so, and many slaves were not allowed to hold money. Slaves were also freed through testamentary manumission, by a provision in an owner's will at his death. Augustus restricted such manumissions to at most a hundred slaves, and fewer in a small household.

Already educated or experienced slaves were freed the most often. Eventually the practice became so common that Augustus decreed that no Roman slave could be freed before age 30.

Freedmen

A freed slave was the libertus of his former master, who became his patron (patronus). The two had mutual obligations to each other within the traditional patronage network. The terms of his manumission might specify the services a libertus owed. A freedman could "network" with other patrons as well.

As a social class, former slaves were libertini. Men could vote and participate in politics, with some limitations. They could not run for office, nor be admitted to the senatorial class. The children of former slaves enjoyed the full privileges of Roman citizenship without restrictions. The Latin poet Horace was the son of a freedman, and an officer in the army of Marcus Junius Brutus.

Some freedmen became very powerful. Many freedmen had important roles in the Roman government. Freedmen of the Imperial families often were the main functionaries in the Imperial administration. Some rose to positions of great influence, such as Narcissus, a former slave of the Emperor Claudius.

Other freedmen became wealthy. The brothers who owned House of the Vettii, one of the biggest and most magnificent houses in Pompeii, are thought to have been freedmen. A freedman designed the amphitheater in Pompeii.

A freedman who became rich and influential might still be looked down on by the traditional aristocracy as a vulgar nouveau riche. Trimalchio, a character in the Satyricon, is a caricature of such a freedman.

References

- Described by Mikhail Rostovtzev, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire (Tannen, 1900), p. 288.

- Fields, Nic. Spartacus and the Slave War 73–71 BC: A Gladiator Rebels against Rome. (Osprey 2009) p. 17–18.

- Roman Slavery: The Social, Cultural, Political, and Demographic Consequences by Moya K. Mason

- Brian Tierney, The Idea of Natural Rights (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2002, originally published 1997 by Scholars Press for Emory University), p. 136.

- R.W. Dyson, Natural Law and Political Realism in the History of Political Thought (Peter Lang, 2005), vol. 1, p. 127.

- David J. Bederman, International Law in Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 85.

- Bradley (1994), pp. 33–34, 48–49

- Mouritsen (2011), p. 100

- Dupont p. 63.

- Tim Cornell 'The Recovery of Rome' in CAH2 7.2 F.W. Walbank et al. (eds.) Cambridge.

- Wickham (2014), pp. 210–217

- W.V. Harris. 1979. War and Imperialism in Republican Rome 327–70 B.C.. Oxford, p. 59 n. 4.

- Fields, pp. 7, 8–10.

- K.R. Bradley. 2004. 'On Captives under the Principate', Phoenix 58,3/4:, 299; Brunt 1971 Italian Manpower, Oxford, p. 707; Hopkins 1978, pp. 8–15. This view has been challenged more recently by Wickham (2014).

- Bradley 2004, pp. 298–318.

- V. Gabrielsen 'Piracy and the Slave-Trade' in A. Erskine (ed.) A Companion to the Hellenistic World (London, 2003) pp. 389–404.

- Plutarch, Pompey 24-8.

- St. Augustine Letter 10.

- Hopkins, Keith. Conquerors and Slaves: Sociological Studies in Roman History. Cambridge University Press, New York. Pgs. 4–5

- Herodotus, Histories 9.10.

- Finley, Moses I. (1960). Slavery in classical Antiquity. Views and controversies. Cambridge.

- Finley, Moses I. (1980). Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology. Chatto & Windus.

- Montoya Rubio, Bernat (2015). L'esclavitud en l'economia antiga: fonaments discursius de la historiografia moderna (Segles XV-XVIII). Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté. pp. 15–25. ISBN 978-2-84867-510-7.

- Harris (2000), p. 721

- Harris (2000), p. 722

- Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to History

- Walter Scheidel. 2005. 'Human Mobility in Roman Italy, II: The Slave Population', Journal of Roman Studies 95: 64–79. Scheidel, p. 170, has estimated between 1 and 1.5 million slaves in the 1st century BC.

- Wickham (2014), p. 198 notes the difficulty in estimating the size of the slave population and the supply needed to maintain and grow the population.

- No contemporary or systematic census of slave numbers is known; in the Empire, under-reporting of male slave numbers would have reduced the tax liabilities attached to their ownership. See Kyle Harper, Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425. Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp. 58–60, and footnote 150. ISBN 978-0-521-19861-5

- Bruce W. Frier and Thomas A. J. McGinn. 2004. A Casebook on Roman Family Law. Oxford University Press: American Philological Association. p. 15

- Stefan Goodwin. 2009. Africa in Europe: Antiquity into the Age of Global Expansion. Lexington Books. vol. 1, p. 41, noting that "Roman slavery was a nonracist and fluid system".

- Noy, David (2000). Foreigners at Rome: Citizens and Strangers. Duckworth with the Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-0-7156-2952-9.

- Harper, James (1972). Slaves and Freedmen in Imperial Rome. Am J Philol.

- Prowse, Tracy L.; Schwarcz, Henry P.; Garnsey, Peter; Knyf, Martin; MacChiarelli, Roberto; Bondioli, Luca (2007). "Isotopic evidence for age-related immigration to imperial Rome". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 510–519. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20541. PMID 17205550.

- Killgrove, Kristina; Montgomery, Janet (2016). "All Roads Lead to Rome: Exploring Human Migration to the Eternal City through Biochemistry of Skeletons from Two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st–3rd c AD)". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0147585. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147585K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147585. PMC 4749291. PMID 26863610.

- Wickham (2014), pp. 180–184

- This is contested by Wickham (2014), pp. iv, 202–205.

- William L. Westermann, The slave systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity, The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, US.

- de souza,Philip:"the roman news" , page 11. Candlewick press, 1996.;

- Roman Society, Roman Life

- Johnston, Mary. Roman Life. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, 1957, p. 158–177

- P.A. Brunt, Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic (Chatto & Windus, 1971), pp. 56–57.

- Brunt, Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic, pp. 56–57.

- "Slavery in Rome," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 323.

- Roman Civilization Archived 2009-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- CIL VI, 6246.

- Alfred Michael Hirt, Imperial Mines and Quarries in the Roman World: Organizational Aspects 27–BC AD 235 (Oxford University Press, 2010), sect. 3.3.

- Hirt, Imperial Mines and Quarries, sect. 4.2.1.

- Alison Futrell, A Sourcebook on the Roman Games (Blackwell, 2006), p. 124.

- Adolf Berger. 1991. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law. American Philosophical Society (reprint). p. 706.

- Marcel Mauss. 1979. "A Category of the human mind: the notion of the person, the notion of 'self'". In: Marcel Mauss. 1979. Sociology and psychology. Essays. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 81.

- Ingram, John Kells (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 216–227.

- Fergus Millar, The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic (University of Michigan, 1998, 2002), pp. 23, 209.

- Mouritsen (2011), p. 36

- Adolf Berger, entry on libertus, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philological Society, 1953, 1991), p. 564.

- Berger, entry on libertinus, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law, p. 564.

- Jane F. Gardner. 2011. "Slavery and Roman Law," in The Cambridge World History of Slavery. Cambridge University Press. vol. 1, p. 429.

- Gamauf (2009)

- Kehoe, Dennis P. (2011). "Law and Social Function in the Roman Empire". The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World. Oxford University Press. pp. 147–8.

- Bradley (1994), pp. 2–3

- Cicero, Ad familiares 16.21

- Jerome, Chronological Tables 194.1

- William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology vol. 3, p. 1182 Archived 2006-12-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Slavery in the Roman Empire".

- Dillon, Matthew and Garland, Lynda. Ancient Rome: From the Early Republic to the Assassination of Julius Caesar. Routledge, 2005. Pg 297

- McGinn, Thomas. Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press, 2003 Pg. 309

- Maylor, Adrienne The Poison King Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010 page 20.

- Maylor, Adrienne The Poison King Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010 pages 20–21.

- Strauss, pp. 190–194, 204

- Fields, pp. 79–81

- Losch, p. 56, n. 1

- see also Philippians 2:5–8.

- Bradley, Keith Resisting Slavery in Ancient Rome

- Naerebout and Singor, "De Oudheid", p. 296

- Siculus, Diodorus. The Civil Wars 111–121. 73–71 BC

- Mackay, Christopher (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0521809184.

- H.S. Versnel, "Saturnus and the Saturnalia," in Inconsistencies in Greek and Roman Religion: Transition and Reversal in Myth and Ritual (Brill, 1993, 1994), p. 147

- Dolansky (2010), p. 492

- Seneca, Epistulae 47.14

- Barton (1993), p. 498

- Dolansky (2010), p. 484

- Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.24.22–23

- Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price, Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook (Cambridge University Press, 1998), vol. 2, p. 124.

- Horace, Satires 2.7.4

- Hans-Friedrich Mueller, "Saturn", in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 221,222.

- Horace, Satires, Book 2, poems 3 and 7

- Catherine Keane, Figuring Genre in Roman Satire (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 90

- Maria Plaza, The Function of Humour in Roman Verse Satire: Laughing and Lying (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 298–300 et passim.

- Barton (1993), passim

- Richard P. Saller, "Symbols of Gender and Status Hierarchies in the Roman Household," in Women and Slaves in Greco-Roman Culture (Routledge, 1998; Taylor & Francis, 2005), p. 90.

- Plutarch, Roman Questions 100

- Saller, "Symbols of Gender and Status Hierarchies," p. 91.

- Servius, in his note to Aeneid 8.564, citing Varro.

- Livy, 22.1.18

- Peter F. Dorcey, The Cult of Silvanus: A Study in Roman Folk Religion (Brill, 1992), p. 109.

- Bradley (1994), p. 18

- The calendar of Polemius Silvius is the only one to record the holiday.

- William Warde Fowler, The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic (London, 1908), p. 176.

- Plutarch, Life of Camillus 33, as well as Silvius.

- By Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.11.36

- Jennifer A. Glancy, Slavery in Early Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2002; First Fortress Press, 2006), p. 27

- K.R. Bradley, "On the Roman Slave Supply and Slavebreeding," in Classical Slavery (Frank Cass Publishers, 1987, 1999, 2003), p. 63.

- Clauss (2001), pp. 33, 37–39

- Clauss (2001), pp. 40, 143

- Ephesians 6:5–9

- Colossians 4:1

- 1Corinthians 7:21.

- "1 Peter 2:18 Slaves, in reverent fear of God submit yourselves to your masters, not only to those who are good and considerate, but also to those who are harsh". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- Catholic Encyclopedia Slavery and Christianity

- Isaac, Benjamin (2006). "Proto-Racism in Graeco-Roman Antiquity". World Archaeology. 38 (1): 32–47. doi:10.1080/00438240500509819.

- Westermann, William Linn (1942). "Industrial Slavery in Roman Italy". The Journal of Economic History. 2 (2): 161. doi:10.1017/S0022050700052542.

- Hopkins, Keith (1993). "Novel Evidence for Roman Slavery". Past & Present. 138: 6, 8. doi:10.1093/past/138.1.3.

- Mellor, Ronald. The Historians of Ancient Rome. New York: Routledge, 1997. (467).

- Cicero. Ad familiares 16.6

- Bankston (2012), p. 209

- Cicero. Ad familiares 16.3

- Bankston (2012), p. 215

- Segal, Erich. Roman Laughter: The Comedy of Plautus. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968. (99–169).

- Stewart, Roberta (2012). Plautus and Roman Slavery. Malden, MA: Oxford.

- Terence, Terence (2002). Andria. Bristol Classical Press.

Bibliography

- Bankston, Zach (2012). "Administrative Slavery in the Ancient Roman Republic: The Value of Marcus Tullius Tiro in Ciceronian Rhetoric". Rhetoric Review. 31 (3): 203–218. doi:10.1080/07350198.2012.683991.

- Barton, Carlin A. (1993). The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster. Princeton University Press.

- Bradley, Keith (1994). Slavery and Society at Rome. Cambridge University Press.

- Clauss, Manfred (2001). The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries. Translated by Richard Gordon. Routledge.

- Dolansky, Fanny (2010). "Celebrating the Saturnalia: religious ritual and Roman domestic life". In Beryl Rawson (ed.). A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 488–503. doi:10.1002/9781444390766.ch29. ISBN 978-1-4051-8767-1.

- Gamauf, Richard (2009). "Slaves Doing Business: The role of Roman Law in the Economy of a Roman Household". European Review of History. 16 (3): 331–346. doi:10.1080/13507480902916837.

- Harris, W. V. (2000). "Trade". The Cambridge Ancient History: The High Empire A.D. 70–192. 11. Cambridge University Press.

- Mouritsen, Henrik (2011). The Freedman in the Roman World. Cambridge University Press.

- Santosuosso, Antonio (2001). Storming the Heavens. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3523-0.

- Wickham, Jason Paul (2014). The Enslavement of War Captives by the Romans to 146 BC (PDF) (PhD thesis). Liverpool University.

Further reading

- Bosworth, A. B. 2002. "Vespasian and the Slave Trade." Classical Quarterly 52:350–357.

- Bradley, Keith. 1994. Slavery and Society at Rome. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Fitzgerald, William. 2000. Slavery and the Roman Literary Imagination. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Hopkins, Keith. 1978. Conquerors and Slaves. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Hunt, Peter. 2018. Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery. Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Joshel, Sandra R.. 2010. Slavery in the Roman World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Watson, Alan. 1987. Roman Slave Law. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

- Yavetz, Zvi. 1988. Slaves and Slavery in Ancient Rome. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slavery in ancient Rome. |

| Library resources about Slavery in ancient Rome |