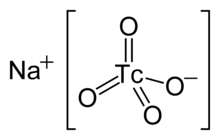

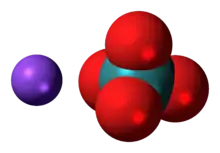

Sodium pertechnetate

Sodium pertechnetate is the inorganic compound with the formula NaTcO4. This colourless salt contains the pertechnetate anion, [TcO4]−. The radioactive 99mTcO4− anion is an important radiopharmaceutical for diagnostic use. The advantages to 99mTc include its short half-life of 6 hours and the low radiation exposure to the patient, which allow a patient to be injected with activities of more than 30 millicuries.[1] Na[99mTcO4] is a precursor to a variety of derivatives that are used to image different parts of the body.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sodium technetate(VII) | |

| Other names

sodium tetraoxotechnetate (VII) | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.870 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| NaTcO4 | |

| Molar mass | 169.89 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or pale pink solid |

| Soluble | |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

Sodium permanganate; sodium perrhenate |

Other cations |

Ammonium pertechnetate |

Related compounds |

Technetium heptoxide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Chemistry

[TcO4]− is the starting material for most of the chemistry of technetium. Pertechnetate salts are usually colorless.[2] [TcO4]− is produced by oxidizing technetium with nitric acid or with hydrogen peroxide. The pertechnetate anion is similar to the permanganate anion but is a weaker oxidizing agent. It is tetrahedral and diamagnetic. The standard electrode potential for TcO4−/TcO2 is only +0.738 V in acidic solution, as compared to +1.695 V for MnO4−/MnO2.[1] Because of its diminished oxidizing power, [TcO4]− is stable in alkaline solution. [TcO4]− is more similar to ReO4−. Depending on the reducing agent, [TcO4]− can be converted to derivatives containing Tc(VI), Tc(V), and Tc(IV).[3] In the absence of strong complexing ligands, TcO4− is reduced to a +4 oxidation state via the formation of TcO2 hydrate.[1]

Pharmaceutical use

The half-life of 99mTc is long enough that labelling synthesis of the radiopharmaceutical and scintigraphic measurements can be performed without significant loss of radioactivity.[1] The energy emitted from 99mTc is 140 keV, which allows for the study of deep body organs. Radiopharmaceuticals have no intended pharmacologic effect and are used in very low concentrations. Radiopharmaceuticals containing 99mTc are currently being applied in the determining morphology of organs, testing of organ function, and scintigraphic and emission tomographic imaging. The gamma radiation emitted by the radionuclide allows organs to be imaged in vivo tomographically. Currently, over 80% of radiopharmaceuticals used clinically are labelled with 99mTc. A majority of radiopharmaceuticals labelled with 99mTc are synthesized by the reduction of the pertechnetate ion in the presence of ligands chosen to confer organ specificity of the drug. The resulting 99mTc compound is then injected into the body and a "gamma camera" is focused on sections or planes in order to image the spatial distribution of the 99mTc.

Specific imaging applications

99mTc is used primarily in the study of the thyroid gland - its morphology, vascularity, and function. [TcO4]− and iodide, due to their comparable charge/radius ratio, are similarly incorporated into the thyroid gland. The pertechnetate ion is not incorporated into the thyroglobulin. It is also used in the study of blood perfusion, regional accumulation, and cerebral lesions in the brain, as it accumulates primarily in the choroid plexus.

Sodium pertechnetate cannot pass through the blood–brain barrier. In addition to the salivary and thyroid glands, 99mTcO4− localizes in the stomach. 99mTcO4− is renally eliminated for the first three days after being injected. After a scanning is performed, it is recommended that a patient drink large amounts of water in order to expedite elimination of the radionuclide.[4] Other methods of 99mTcO4− administration include intraperitoneal, intramuscular, subcutaneous, as well as orally. The behavior of the 99mTcO4− ion is essentially the same, with small differences due to the difference in rate of absorption, regardless of the method of administration.[5]

Preparation of 99mTcO4−

99mTc is conveniently available in high radionuclidic purity from molybdenum-99, which decays with 87% probability to 99mTc. The subsequent decay of 99mTc leads to either 99Tc or 99Ru. 99Mo can be produced in a nuclear reactor via irradiation of either molybdenum-98 or naturally occurring molybdenum with thermal neutrons, but this is not the method currently in use today. Currently, 99Mo is recovered as a product of the nuclear fission reaction of 235U,[6] separated from other fission products via a multistep process and loaded onto a column of alumina that forms the core of a 99Mo/99mTc radioisotope "generator".

As the 99Mo continuously decays to 99mTc, the 99mTc can be removed periodically (usually daily) by flushing a saline solution (0.15 M NaCl in water) through the alumina column: the more highly charged 99MoO42− is retained on the column, where it continues to undergo radioactive decay, while the medically useful radioisotope 99mTcO4− is eluted in the saline. The eluate from the column must be sterile and pyrogen free, so that the Tc drug can be used directly, usually within 12 hours of elution.[1] In a few cases, sublimation or solvent extraction may be used.

Synthesis of 99mTcO4− radiopharmaceuticals

99mTcO4− is advantageous for the synthesis of a variety of radiopharmaceuticals because Tc can adopt a number of oxidation states.[1] The oxidation state and coligands dictate the specificity of the radiopharmaceutical. The starting material Na99mTcO4, made available after elution from the generator column, as mentioned above, can be reduced in the presence of complexing ligands. Many different reducing agents can be used, but transition metal reductants are avoided because they compete with 99mTc for ligands. Oxalates, formates, hydroxylamine, and hydrazine are also avoided because they form complexes with the technetium. Electrochemical reduction is impractical.

Ideally, the synthesis of the desired radiopharmaceutical from 99mTcO4−, a reducing agent, and desired ligands should occur in one container after elution, and the reaction must be performed in a solvent that can be injected intravenously, such as a saline solution. Kits are available that contain the reducing agent, usually tin(II) and ligands. These kits are sterile, pyrogen-free, easily purchased, and can be stored for long periods of time. The reaction with 99mTcO4− takes place directly after elution from the generator column and shortly before its intended use. A high organ specificity is important because the injected activity should accumulate in the organ under investigation, as there should be a high activity ratio of the target organ to nontarget organs. If there is a high activity in organs adjacent to the one under investigation, the image of the target organ can be obscured. Also, high organ specificity allows for the reduction of the injected activity, and thus the exposure to radiation, in the patient. The radiopharmaceutical must be kinetically inert, in that it must not change chemically in vivo en route to the target organ.

Examples

- A complex that can penetrate the blood–brain barrier is generated by reduction of 99mTcO4− with tin(II) in the presence of the ligand "d,l-HMPAO" to form TcO-d,l-HMPAO (HM-PAO is hexamethylpropyleneamino oxime).

- A complex that for imaging the lungs, "Tc-MAA," is generated by reduction of 99mTcO4− with SnCl2 in the presence of human serum albumin.

- [99mTc(OH2)3(CO)3]+, which is both water and air stable, is generated by reduction of 99mTcO4− with carbon monoxide. This compound is a precursor to complexes that can be used in cancer diagnosis and therapy involving DNA-DNA pretargeting.[7]

Other reactions involving the pertechnetate ion

- Radiolysis of TcO4− in nitrate solutions proceeds through the reduction to TcO42− which induces complex disproportionation processes:

- Pertechnetate can be reduced by H2S to give Tc2S7.[8]

- Pertechnetate is also reduced to Tc(IV/V) compounds in alkaline solutions in nuclear waste tanks without adding catalytic metals, reducing agents, or external radiation. Reactions of mono- and disaccharides with 99mTcO4− yield Tc(IV) compounds that are water-soluble.[9]

References

- Schwochau, K. (1994). "Technetium Radiopharmaceuticals-Fundamentals, Synthesis, Structure, and Development". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 33 (22): 2258–2267. doi:10.1002/anie.199422581.

- Wells, A. F.; Structural Inorganic Chemistry; Clarendon Press: Oxford, Great Britain; 1984; p. 1050.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Technetium

- Shukla, S. K., Manni, G. B., and Cipriani, C. (1977). "The Behaviour of the Pertechnetate Ion in Humans". Journal of Chromatography B. 143 (5): 522–526. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(00)81799-5. PMID 893641.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Razzak, M. A.; Naguib, M.; El-Garhy, M. (1967). "Fate of Sodium Pertechnetate-Technetium-99m". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 8 (1): 50–59. PMID 6019138.

- Beasley, T. M., Palmer, H. E., and Nelp, W. B. (1966). "Distribution and Excretion of Technetium in Humans". Health Physics. 12 (10): 1425–1435. doi:10.1097/00004032-196610000-00004. PMID 5972440.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- R. Alberto, R. Schibli, A. Egli, A. P. Schubiger, U. Abram and T. A. Kaden (1998). "A Novel Organometallic Aqua Complex of Technetium for the Labeling of Biomolecules: Synthesis of [99mTc(OH2)3(CO)3]+ from [99mTcO4]− in Aqueous Solution and Its Reaction with a Bifunctional Ligand". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 (31): 7987–7988. doi:10.1021/ja980745t.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Emeléus, H. J.; Sharpe, A. G. (1968). Advances in Inorganic Chemistry and Radiochemistry, Volume 11. Academic Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-08-057860-6.

- D. E. Berning, N. C. Schroeder and R. M. Chamberlin (2005). "The autoreduction of pertechnetate in aqueous, alkaline solutions". Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 263 (3): 613–618. doi:10.1007/s10967-005-0632-x. S2CID 95071892.