Sour beer

Sour beer is beer which has an intentionally acidic, tart, or sour taste. Traditional sour beer styles include Belgian lambics, gueuze and Flanders red ale, and German gose.

Brewing

Unlike modern brewing, which is done in a sanitary environment to guard against the intrusion of wild yeast,[1] historically the starter used from one batch to another usually contained some wild yeast and bacteria.[2] Sour beers are made by intentionally allowing wild yeast strains or bacteria into the brew, traditionally through the barrels or during the cooling of the wort in a coolship open to the outside air.[3][4]

The most common microbes used to intentionally sour beer are bacteria Lactobacillus and Pediococcus, while Brettanomyces can also add some acidity.[1] Another method for achieving a tart flavor is adding fruit, which directly contributes organic acids such as citric acid.[4][5] Additionally, acid can be directly added to beer or added by the use of excessive amounts of acidulated malt.

Depending on the process employed, the uncertainty involved in using wild yeast may cause the beer to take months to ferment and potentially years to mature.[1] However, modern methods allow sour beer to be created within a typical timeframe for ales, several days.[6]

Breweries

Making sour beer is a risky and specialized form of beer brewing, and longstanding breweries which produce it and other lambics often specialize in this and other Belgian-style beers. Established in 1836, one of the oldest breweries still in operation that produces sour beer is the Rodenbach Brewery of Roeselare, Belgium.[7] Sour beer has also spread outside Belgium, to other European countries, the United States and Canada.

In the United Kingdom sour ales are produced by Elgood's, a brewery in Wisbech.

Sour beer styles

While any type of beer may be soured, most follow traditional or standardized guidelines.

American wild ale

Beers brewed in the United States utilizing yeast and bacteria strains instead of or in addition to standard brewers yeasts. These microflora may be cultured or acquired spontaneously, and the beer may be fermented in a number of different types of brewing vessels. American wild ales tend not to have specific parameters or guidelines stylistically, but instead simply refer to the use of unusual yeasts.

Berliner Weisse

At one time the most popular alcoholic beverage in Berlin, this is a somewhat weaker (usually around 3% abv) beer made sour by use of Lactobacillus bacteria. This type of beer is usually served with flavored syrups to balance the tart flavor.[8]

Flanders red ale

Flanders red ales are fermented with brewers yeast, then placed into oak barrels to age and mature. Usually, the mature beer is blended with younger beer to adjust the taste for consistency. This is also sometimes referred to as "flemish red".[9]

Gose

Gose is a top-fermenting beer that originated in Goslar, Germany. This style is characterized by the use of coriander and salt and is made sour by inoculating the wort with lactic acid bacteria before primary fermentation.

Lambic

Lambic is a spontaneously-fermented beer made in the Pajottenland region around Brussels, Belgium. Wort is left to cool overnight in the koelschip where it is exposed to the open air during the winter and spring, and placed into barrels to ferment and mature. Most lambics are blends of several season's batches, such as gueuze, or are secondarily fermented with fruits, such as kriek and framboise. As such, pure unblended lambic is quite rare, and few bottled examples exist.

Oud bruin

Originating from the Flemish region of Belgium, oud bruins are differentiated from the Flanders red ale in that they are darker in color and not aged on wood. As such this style tends to use cultured yeasts to impart its sour notes.

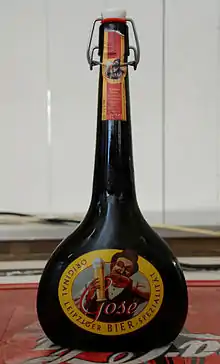

Gallery of European sour beer styles

See also

References

- Greg Koch; Matt Allyn (1 October 2011). The Brewer's Apprentice: An Insider's Guide to the Art and Craft of Beer Brewing, Taught by the Masters. Rockport Publishers. pp. 91–93. ISBN 978-1-59253-731-0. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Zhang, Sarah (27 June 2014). "Using Yeast DNA To Unlock a Better Beer". Gawker. Gizmodo. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "The Coolships Have Landed". Table Matters. 2014-02-14. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- Lurie, Joshua (July 1, 2009). "Sour beer? Pucker up". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- Charlie Papazian (11 September 2003). The complete joy of homebrewing. HarperCollins. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-06-053105-8. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- https://www.homebrewtalk.com/forum/threads/fast-souring-modern-methods.670176/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Oliver, Garrett (21 April 2005). The Brewmaster's Table: Discovering the Pleasures of Real Beer with Real Food. HarperCollins. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-06-000571-9. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- The World Guide to Beer, Michael Jackson, Mitchell Beazley, ISBN 0-85533-126-7

- "Everything You Need To Know About Sour Beer". 2018-08-23.