Sparkbrook

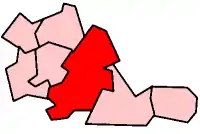

Sparkbrook is an inner-city area in south-east Birmingham, England. It is one of the four wards forming the Hall Green formal district within Birmingham City Council.

| Sparkbrook | |

|---|---|

Sparkbrook Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 32,415 (2011.Ward)[1] |

| • Density | 79.8 per ha |

| OS grid reference | SP087849 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B11 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Etymology

The area receives its name from Spark Brook, a small stream that flowed south of the city centre. It was later channelled and partially used for a canal.

Politics

Sparkbrook ward is represented by three Labour councillors on Birmingham City Council, Mohammed Azim and Shabrana Hussain.[2]

Its former independent councillor, Talib Hussain, was elected as a Liberal Democrat but resigned from the party after being sacked from the council's cabinet.[3]

Project Champion

Project Champion is a project to install a £3m network of 169 Automatic Number Plate Recognition cameras to monitor vehicles entering and leaving Sparkbrook and Washwood Heath. Its implementation was frozen in June 2010 amid allegations that the police deliberately misled councillors about its purpose, after it was revealed that it was being funded as an anti-terrorism initiative, rather than for 'reassurance and crime prevention'.[4][5] The campaign was spearheaded by a local activist called Steve Jolly,[6] who 'wrote an article for a local magazine, started a petition and lobbied MPs and councillors to denounce the spy-cam scheme',[7] he was proactive in contacting the media, it was Steve Jolly who made Paul Lewis of The Guardian aware of this issue. When Paul Lewis wrote his article,[8] it sparked national and international debate on Project Champion, this then led to massive public resistance to Project Champion, which eventually led to it being stopped. West Midlands Police were forced into making an apology.[9] Chief Constable Simms said: "I am sorry that we got such an important issue so wrong and deeply sorry that it has had such a negative impact on our communities."[10]

Places of interest

Many of the churches within Sparkbrook were constructed in the late 19th century and early 20th century. One of the most prominent churches in the area is St Agatha's Church on the Stratford Road, consecrated in 1901. It is a Grade I listed building.[11][12]

Christ Church, on the corner of Grantham Road and Dolobran Road, was one of the oldest churches in the area, being consecrated in 1867. The spire belonging to the tower was removed in 1918, and following a bomb blast in World War II, the tower was demolished. In 1927, The Diocesan Home for Girls received a licence permitting public worship within the building.[13] Following damage caused by the Birmingham Tornado 28 July 2005 the church was demolished.[14][15]

Consecrated in the same year as St Agatha's Church, Emmanuel Church, was a chapel of ease to Christ Church until it received its own parish in 1928. Located within the church is an ancient blank bell from Ullenhall.[16]

Ladypool Road mission hall was opened in 1894 by the Sparkbrook Gospel Mission (founded 1886).[17]

In 1849, a group called the Methodist New Connexion, opened a chapel in the area, their first for 11 years along with a similar chapel on Bridge Street in the city centre.[18]

Lloyd House is a Georgian building situated on Sampson Road. It was built between 1742 and 1752 by Sampson Lloyd, the founder of Lloyds Bank. The building is used as offices by the Bromford Corinthia Housing Association.

In 1780, Sparkbrook was the home of Joseph Priestley, one of the founding fathers of modern chemistry. In 1791, his mansion was partially destroyed in what became known as the Priestley riots. It stood on what is now Priestley Road.

Unemployment

The late 2000s recession resulted in Sparkbrook and Small Heath ward having the eighth highest level of unemployment in Britain in 2009, with 12.9% (more than one in eight) of its residents being registered unemployed. Only Ladywood had a higher rate of unemployment in the West Midlands.[19]

Demographics

The 2001 Census recorded that 31,485 people were living in the ward. Sparkbrook has the second highest non-white population in Birmingham, with a total of 78%[20] minority ethnic residents living in the mainly terraced area; notably it is home to a large Somali population. Sparkbrook is also the location of Birmingham's "Balti Triangle", and many of the residents have their own balti businesses.

See also

- Roy Hattersley, Baron Hattersley of Sparkbrook in the County of West Midlands.

- Farm, Bordesley

- Ladypool Primary School

- Sparkbrook and Small Heath

- UB40

References

- "Birmingham ward population 2011". Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Councillors' Advice Bureaux – Sparkbrook Ward

- "Cabinet 'racism' claim". Birmingham Mail. 27 September 2005. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- Police under fire over Muslim CCTV surveillance scheme, The Guardian, published 2010-06-18. Retrieved 14 August 2010

- Birmingham stops Muslim CCTV surveillance scheme, The Guardian, 2010-06-17. Retrieved 14 August 2010

- , The Guardian, 2010-06-23. Retrieved 17 February 2011

- , The Guardian, 2010-06-23. Retrieved 17 February 2011

- Police under fire over Muslim CCTV surveillance scheme, The Guardian, published 2010-06-18. Retrieved 14 August 2010

- , Sky News, published 2010-09-30. Retrieved 13 February 2011

- , The Independent, published 2010-09-30. Retrieved 13 February 2011

- Saint Agatha's Church website

- British History Online: St Agatha Church entry

- British History Online: Christ Church entry

- Indymedia UK – After the tornado: "market forces" force demolition of Sparkbrook Church

- Ecclesiastical Law Society Archived 11 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- British History Online: Emmanuel entry

- British History Online: A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 7: The City of Birmingham – Religious History

- British History Online: Protestant Nonconformity

- 2001 Census