Sphalerite

Sphalerite ((Zn, Fe)S) is a mineral that is the chief ore of zinc. It consists largely of zinc sulfide in crystalline form but almost always contains variable iron. When iron content is high it is an opaque black variety, marmatite. It is usually found in association with galena, pyrite, and other sulfides along with calcite, dolomite, and fluorite. Miners have also been known to refer to sphalerite as zinc blende, black-jack and ruby jack.

| Sphalerite | |

|---|---|

Black crystals of sphalerite with minor chalcopyrite and calcite | |

| General | |

| Category | Sulfide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | (Zn,Fe)S |

| Strunz classification | 2.CB.05a |

| Dana classification | 02.08.02.01 |

| Crystal system | Cubic |

| Crystal class | Hextetrahedral (43m) H-M symbol: (4 3m) |

| Space group | F43m (No. 216) |

| Unit cell | a = 5.406 Å; Z = 4 |

| Structure | |

| Jmol (3D) | Interactive image |

| Identification | |

| Color | Light to dark brown, red-brown, yellow, red, green, light blue, black and colourless. |

| Crystal habit | Euhedral crystals – occurs as well-formed crystals showing good external form. Granular – generally occurs as anhedral to subhedral crystals in matrix. |

| Twinning | Simple contact twins or complex lamellar forms, twin axis [111] |

| Cleavage | perfect |

| Fracture | Uneven to conchoidal |

| Mohs scale hardness | 3.5-4 |

| Luster | Adamantine, resinous, greasy |

| Streak | brownish white, pale yellow |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent, opaque when iron-rich |

| Specific gravity | 3.9–4.2 |

| Optical properties | Isotropic |

| Refractive index | nα = 2.369 |

| Other characteristics | non-radioactive, non-magnetic, fluorescent and triboluminescent. |

| References | [1][2][3] |

Chemistry

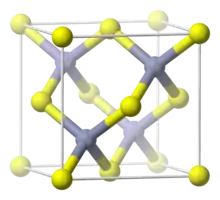

The mineral crystallizes in the cubic crystal system. Like other minerals with a cubic crystal structure, sphalerite may show a tetrahedral crystal habit. In the crystal structure, zinc and sulfur atoms are tetrahedrally coordinated. The structure is closely related to the structure of diamond. The hexagonal analog is known as the wurtzite structure. The lattice constant for zinc sulfide in the zinc blende crystal structure is 0.541 nm.[4]

All natural sphalerites contain concentrations of various impurity elements. These generally substitute for the zinc position in the lattice. The most common are Cd and Mn, but Gallium, Germanium and Indium may also be present in relatively high concentrations (hundreds to thousands of ppm).[5] The abundances of these elements are controlled by the conditions under which the sphalerite formed, most importantly formation temperature and fluid composition.[5]

Varieties

Its color is usually yellow, brown, or gray to gray-black, and it may be shiny or dull. Its luster is adamantine, resinous to submetallic for high iron varieties. It has a yellow or light brown streak, a Mohs hardness of 3.5–4, and a specific gravity of 3.9–4.1. Some specimens have a red iridescence within the gray-black crystals; these are called "ruby sphalerite". The pale yellow and red varieties have very little iron and are translucent. The darker, more opaque varieties contain more iron. Some specimens are also fluorescent in ultraviolet light.

The refractive index of sphalerite (as measured via sodium light, average wavelength 589.3 nm) is 2.37. Sphalerite crystallizes in the isometric crystal system and possesses perfect dodecahedral cleavage.

Gemmy, pale specimens from Franklin, New Jersey (see Franklin Furnace), are highly fluorescent orange and/or blue under longwave ultraviolet light and are known as cleiophane, an almost pure ZnS variety.

Occurrence

Sphalerite is the major ore of zinc and is found in thousands of locations worldwide.[2]

Sources of high quality crystals include:[3]

| Place | Country | Type of crystal |

|---|---|---|

| Freiberg, Saxony, Neudorf, Harz Mountains | Germany | |

| Lengenbach Quarry, Binntal, Valais | Switzerland | Colorless |

| Horni Slavkov and Příbram | Czech Republic | |

| Rodna | Romania | |

| Madan, Smolyan Province, Rhodope Mountains | Bulgaria | Transparent green to opaque black |

| Aliva mine, Picos de Europa Mountains, Cantabria [Santander] Province | Spain | Transparent |

| Alston Moor, Cumbria | England | black |

| Dalnegorsk, Primorskiy Kray | Russia | |

| Watson Lake, Yukon Territory | Canada | |

| Flin Flon, Manitoba | Canada | |

| Tri-State district including deposits near Baxter Springs, Cherokee County, Kansas; Joplin, Jasper County, Missouri and Picher, Ottawa County, Oklahoma | USA | |

| Elmwood mine, near Carthage, Smith County, Tennessee | USA | |

| Eagle mine, Gilman district, Eagle County, Colorado | USA | |

| Santa Eulalia, Chihuahua | Mexico | |

| Naica, Chihuahua | Mexico | |

| Cananea, Sonora | Mexico | |

| Huaron | Peru | |

| Casapalca | Peru | |

| Huancavelica | Peru | |

| Zinkgruvan | Sweden |

Economic importance

Sphalerite is the most important ore of zinc. Around 95% of all primary zinc is extracted from sphaleritic ores. However, due to its variable trace element content, sphalerite is also an important source of several other elements, such as cadmium,[6] gallium[7] germanium,[8] and indium.[9]

Gemstone use

Crystals of suitable size and transparency have been fashioned into gemstones, usually featuring the brilliant cut to best display sphalerite's high dispersion of 0.156 (B-G interval), over three times that of diamond. Freshly cut gems have an adamantine luster. Owing to their softness and fragility the gems are often left unset as collector's or museum pieces (although some have been set into pendants). Gem-quality material is usually a yellowish to honey brown, red to orange, or green.

Gallery

Tan crystal of calcite attached to a cluster of black sphalerite crystals

Tan crystal of calcite attached to a cluster of black sphalerite crystals Sharp, tetrahedral sphalerite crystals with minor associated chalcopyrite from the Idarado Mine, Telluride, Ouray District, Colorado, USA

Sharp, tetrahedral sphalerite crystals with minor associated chalcopyrite from the Idarado Mine, Telluride, Ouray District, Colorado, USA Elmwood calcite specimen sitting atop sphalerite

Elmwood calcite specimen sitting atop sphalerite Gem quality twinned cherry-red sphalerite crystal (1.8 cm) from Hunan Province, China

Gem quality twinned cherry-red sphalerite crystal (1.8 cm) from Hunan Province, China_%C3%81liva%252C_Cantabria.jpg.webp) Sphalerite crystals from Áliva, Camaleño, Cantabria (Spain)

Sphalerite crystals from Áliva, Camaleño, Cantabria (Spain) Purple fluorite and sphalerite, from the Elmwood mine, Smith county, Tennessee, US

Purple fluorite and sphalerite, from the Elmwood mine, Smith county, Tennessee, US Shalerite crystal in geodized brachiopod

Shalerite crystal in geodized brachiopod

See also

References

- Sphalerite. Webmineral. Retrieved on 2011-06-20.

- Sphalerite. Mindat.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-20.

- "Handbook of Mineralogy" (PDF).

- International Centre for Diffraction Data reference 04-004-3804, ICCD reference 04-004-3804.

- Frenzel, Max; Hirsch, Tamino; Gutzmer, Jens (July 2016). "Gallium, germanium, indium, and other trace and minor elements in sphalerite as a function of deposit type — A meta-analysis". Ore Geology Reviews. 76: 52–78. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2015.12.017.

- Cadmium - In: USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries. United States Geological Survey. 2017.

- Frenzel, Max; Ketris, Marina P.; Seifert, Thomas; Gutzmer, Jens (March 2016). "On the current and future availability of gallium". Resources Policy. 47: 38–50. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2015.11.005.

- Frenzel, Max; Ketris, Marina P.; Gutzmer, Jens (2014-04-01). "On the geological availability of germanium". Mineralium Deposita. 49 (4): 471–486. Bibcode:2014MinDe..49..471F. doi:10.1007/s00126-013-0506-z. ISSN 0026-4598. S2CID 129902592.

- Frenzel, Max; Mikolajczak, Claire; Reuter, Markus A.; Gutzmer, Jens (June 2017). "Quantifying the relative availability of high-tech by-product metals – The cases of gallium, germanium and indium". Resources Policy. 52: 327–335. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.04.008.

- Dana's Manual of Mineralogy ISBN 0-471-03288-3

- Webster, R., Read, P. G. (Ed.) (2000). Gems: Their sources, descriptions and identification (5th ed.), p. 386. Butterworth-Heinemann, Great Britain. ISBN 0-7506-1674-1

- Minerals.net

- Minerals of Franklin, NJ

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sphalerite. |