Stephen Dee Richards

Stephen D. Richards[13][14][15] or Samuel D. Richards[2][3][4] (March 18, 1856 – April 26, 1879), also known in the media as the "Nebraska Fiend", "Kearney County Murderer", and "The Ohio Monster", was an American serial killer who confessed to committing nine murders[Note 1] in Nebraska and Iowa between 1876 and 1878.

Stephen Dee Richards | |

|---|---|

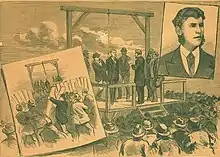

Portrait sketch of Richards, first published in the Nebraska State Journal in 1879 | |

| Born | March 18, 1856 Wheeling, West Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | April 26, 1879 (aged 23) Minden, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Other names | Dick Richardson[1] Samuel D. Richards[2][3][4] Stephen Lee Richards[5][6][7] S.D. Richards[8][9][10] Kearney County Murderer[3] The Nebraska Fiend[5][11] The Ohio Monster[12] |

| Conviction(s) | Murders of the Harlson family and Peter Anderson |

| Criminal penalty | Death by hanging |

| Details | |

| Victims | 9 |

Span of crimes | 1876–1878 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Iowa Nebraska Ohio |

Date apprehended | December 20, 1878 |

Richards was born in West Virginia in 1856. His family would later move to Ohio, eventually settling in the Quaker village of Mount Pleasant. In 1876, Richards left his home and headed westward with the intention of seeking his fortune. For a time, he found work at a local asylum; he claimed that during his time there, he lost all empathy for other people. When Richards later confessed to his crimes, he claimed to have committed his first murder sometime in late 1876, two weeks after arriving in Kearney, Nebraska. He would go on to commit several other murders, which he later claimed were done in self-defense. Richards fled after murdering Mary L. Harlson and her three children, but was captured in Mount Pleasant. In 1879, he was convicted of the murders of the Harlson family, as well as the killing of neighbor Peter Anderson, and hanged.

Richards was regarded as handsome and charismatic by contemporary chroniclers, who noted that his appearance and behavior completely obscured his nature as a cold-blooded killer. Many observed that he displayed a complete lack of remorse for his crimes and indifference toward his execution. Modern-day forensic psychologist Katherine Ramsland has noted that these characteristics were also displayed by Ted Bundy, and she has referred to Richards as The Old West's Ted Bundy.

The nature of Richards' crimes and his behavior after his capture led to a brief period of notoriety, as Richards was widely talked about in the media at the time. Richards has been featured in a handful of books and periodicals, including a posthumous biography, based on an interview conducted after his final arrest. The biography, which also included entries on other criminals of the time, was published in 1879 by the Nebraska State Journal.

Early and young adult life

Stephen Dee Richards was born in Wheeling, West Virginia,[Note 2] on March 18, 1856.[17] He was said to have had five sisters and a brother.[18][19] When Richards was six, his family relocated to Ohio; first to Monroe County, and then to Noble County.[13][17] The family later settled in the Quaker village of Mount Pleasant in Ohio when he was eleven. Richards would later describe his mother as a devout Methodist, and his father, a farmer,[8][9] as having "made no profession of religion".[13] Richards attended school in Mount Pleasant; he claimed that the teachers considered him well-behaved. At his mother's insistence, he also attended Sunday school and church regularly.[13]

Up until the age of twenty, Richards lived with his parents, working for farmers and other locals in the area. On September 16, 1871, Richards' mother died of an unknown cause.[17][20] Several years later, at the age of 20, Richards met and became engaged to a young woman named Anna Millhorne, with whom he regularly corresponded during his later travels, up until his final arrest. Richards also met men whom he would describe as being of "questionable occupation"; he began passing counterfeit bills which he claimed he had obtained by way of a man in New York. In February 1876, he left Mount Pleasant, heading west to find fame and fortune.[21]

For a short time, Richards lived in Iowa, working as a hand at farms in Burlington and Morning Sun. He was later hired as an attendant at the Iowa Lunatic Asylum in Mount Pleasant, Iowa; his job was to bury deceased patients.[21][22][23] The New York Times reported that Richards' time working at the asylum was a significant event in his life that shaped his own humanity and his view of the human race.[22] While Richards would deny witnessing any abuse of the asylum's patients, later reflecting that during his tenure of handling and disposing of deceased patients, he became accustomed to such an extent he came to have little to no regard for humanity.[15][23][24]

Richards left the asylum in October of 1876, and began drifting around the Midwest,[21][22][23] finding intermittent work and occasionally consorting with train robbers. He stayed in Kansas City briefly before moving on to Nebraska, where he passed through Hastings before arriving in Kearney,[25] residing there for a period of two to three weeks before leaving for Cheyenne county.[26] During his stay Richards claimed to have had a part in a number of gunfights, resulting in him shooting each individual, although he admitted to being unaware of their condition after each shooting and whether or not they were killed in the resulting gunfight.[23]

Murders

Early murders

In a confession written after his final arrest, Richards admitted to having killed four men during his travels around Nebraska and Iowa in 1876 and 1877.[27] He claimed to have committed his first murder sometime in late 1876, two weeks after arriving in Kearney.

According to Richards, he met a man while traveling on horseback through the Nebraska countryside, and the pair decided to camp for the night near Dobytown.[28] (Several newspapers reported that the two men's campsite was instead near Sand Hills.)[8][10][29][30] Settling down for the night, the two began gambling in a game of cards, with Richards winning most of the stranger's money. As the two set off for Kearney the following morning, the other man turned on Richards and demanded his money back. Richards refused, whereupon, he claimed, the other man became belligerent. Richards then shot him above the left eye, killing him instantly. After confirming the man was dead, Richards disposed of his body in a nearby river.[28]

Several days later, as he continued his trek to Kearney, Richards encountered another man, who was traveling on foot. The man had seen Richards and the previous traveler together, and the stranger asked what had become of that man. While talking to him, Richards realized that this man and the man whom Richards had killed were friends and business partners.[28][Note 3] Richards denied any knowledge of the dead man, but his friend continued to hound Richards with questions,[26] which caused Richards to become increasingly anxious. Believing the man knew too much, Richards decided to kill the stranger in order to prevent him from disclosing to anyone else his knowledge of the association between Richards and his murder victim. Richards would later say that when the stranger turned his back, he shot him in the back of the head, killing him. He disposed of the corpse and sold the man's horse in a nearby town. He then continued on his way, but before reaching Kearney, stopped at the home of Jasper Harlson,[Note 4] who, according to Richards, was a train robber of some repute.[26] Mary, Jasper's wife,[8][10][34] whom Richards described as being a "free talker", noticed that Richards' shirt was stained with blood, and commented on it. Richards had not noticed blood on his clothes, and claimed to have replied, as if in jest, that it must have come from the men he had murdered. That ended the conversation.[26]

Richards later traveled to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where he used counterfeit money to purchase a horse and buggy from an unidentified man. After Richards left, the seller soon discovered the bills were not genuine. Tracking Richards down, the seller demanded that Richards give him real money or return his horse and buggy.[25] With Richards refusing both demands, the man threatened to have him arrested, and Richards responded by shooting him. He then buried the body and left the area.[35]

In March 1877, Richards and a young man with the surname Gemge left Grand Island, Nebraska, on horseback and headed towards Kearney. As they neared their destination, they stopped and camped for the night between Lowell and Kearney, along the Platte River. Richards woke up at about 3:00 a.m. and roused his partner, telling him it was nearly morning and they should get back on the road. Gemge, infuriated at being awakened so early, began arguing with Richards about the time, and then started insulting him.[36] The argument continued, as Richards later recounted:

"It's a good thing you don't mean all you say," I said. "But I do mean it," he said. "You don't want to mean it," I said; and he picked up his revolver and saying, "Here is something that backs all that I say," cocked it. I looked at him, and thought, "The fool acts as if he means to shoot," and skipping out my little 33 I plugged him one in the head. That was the first trouble we had ever had.[15][24]

Murders of the Harlson family

In June 1878, while in Kearney, Richards was arrested and jailed for larceny. He would later claim that this charge was unfounded.[32] During his time in jail, he reunited with Mary L. Harlson. Shortly before Richards' arrival, she had been arrested under suspicion of having aided the escape of her husband and another prisoner, named Underwood or Nixon, from the Kearney jail.[4][29][37] Richards and Mary Harlson agreed that she would sell him the deed to her property six months later, for $600.[32][38]

After Richards was released from jail, he traveled around Nebraska for several months. He did business in Hastings, Bloomington, and Grand Island before arriving at the Harlsons' Kearney County homestead on October 18, 1878. Mary Harlson transferred the property to Richards upon his arrival, and he stayed there for several weeks.[39] The New York Daily Herald later reported that Richards had married Harlson on November 2, in what the newspaper alleged was a scam to acquire ownership of Harlson's land.[14][29] A month later, Richards decided to kill Harlson and her three children—ten-year-old Daisy, four-year-old Mabel, and two-year-old Jasper, nicknamed "Jesse".[15][29][24] In his confession, Richards claimed that Harlson had discovered that he was guilty of murder, and he feared that her talkative nature might betray his presence to the authorities. In order to silence Harlson, and ensure that his previous crimes would remain hidden, Richards resolved to murder the entire family.[39]

On November 3, 1878, Richards got up early in the morning, along with another man named Brown, who had been staying at the house.[39] Brown left to feed the horses and complete other chores around the farm. Richards found a spade and dug a hole, then sneaked back into the house and murdered Mary, Daisy, Mabel and Jesse with an ax. According to one report, Mary and one of the children were murdered with a smoothing iron, while the other two were physically assaulted.[14][29] Richards would refute this claim, saying he had killed the family while they were asleep.[15][24] He said most of them had died after the first several blows, with the exception of Daisy, who had "writhed in pain for some time".[40] Richards was said to have scrubbed the blood off of the floor and himself after the murders, before sitting down to breakfast.[38] After he had eaten, he carried the bodies out of the house and buried them in the hole he had dug nearby. When later questioned about the Harlsons' disappearance, Richards told several people the family had left with Brown, and he did not know when they would return.[41] A 21st-century account claims that Richards said Harlson had transferred the deed of the farm to him, and subsequently left with her children, to reunite with her husband.[4] The bodies of Harlson and her children were discovered on December 11. Some reports said they had been concealed underneath a haystack,[14] rather than buried, as Richards would later claim.[41]

Murder of Peter Anderson

In December of 1878, Richards agreed to help his neighbor, an immigrant from Sweden named Peter Anderson, with some work on Anderson's property.[41] The Columbus Journal would later report that Richards had used the alias "Dick Richardson" when working for Anderson.[1] On December 9,[4][11] Anderson became ill after eating a meal Richards had prepared, causing him to suspect Richards had poisoned him. Anderson informed a neighbor of his suspicions. The next day, he confronted Richards; the two fought, and Richards either beat Anderson to death with a hammer or hatchet,[22][24][42] or shot him[8][10][33] (contemporary newspaper accounts vary). Anderson's body was later discovered in the cellar of his house, buried underneath a pile of coal.[14] Richards would deny poisoning Anderson, saying that was not his style. He claimed Anderson had attacked him with a knife and that he killed Anderson in self-defense.[19][3]

On the run

Richards decided to flee Kearney shortly after murdering Anderson, expecting that the bodies he had concealed would soon be discovered. In the evening, as he was hitching up Anderson's horses and preparing to leave, some of Anderson's neighbors arrived. They had noticed Anderson's absence and questioned Richards about it. He reportedly told them Anderson was inside the house. As Anderson's neighbors entered the dwelling, Richards fled on horseback, and rode to Bloomington.[2][15][43] He traveled east, by horse and train and on foot, passing through Omaha and Chicago.[Note 5] While on the run, he met up with Jasper Harlson and Harlson's fellow escaped prisoner. The three traveled through Wheeling, West Virginia, and into Ohio, passing through Bridgeport, before arriving in Richards' hometown of Mount Pleasant.[15][22] Nebraska Governor Silas Garber issued an arrest warrant for Richards on December 16, 1878, and promised a reward of $200 for his arrest and conviction.[44]

Capture

Most accounts state that on December 20, 1878,[15] shortly after Richards had arrived in Mount Pleasant, he attended a ballroom dance, accompanied by two unidentified women.[15][45] Copies of a wanted poster featuring Richards had been circulated throughout the town recently, and a constable named McGrew recognized him from the poster. He enlisted the help of a penitentiary guard named Folge; the two men armed themselves with shotguns and set off after Richards. They found him walking through a field just outside of town with the two women. He was unarmed, and quickly surrendered.[15][16][33] Richards would later claim that he had spotted the officers approaching him; intending to fight his way out of the situation, he told the women to head back to town. They refused, however, so Richards chose to surrender.[8][10][33] He said that if the women had left, he would have avoided arrest:

If I hadn't had the two girls with me, I guess the constable, McGrew, who arrested me, would have been a dead man—either of us would, for I'd have shot.[22]

Richards said that if he had escaped, he would have returned to Nebraska. He reasoned that it would have been the last place anyone would look for him.[8][10][33]

Some accounts differed about the date and place of Richards' arrest. The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer said that, upon arriving in a town near Mount Pleasant, Richards was identified by a former acquaintance, who detained him with the help of another person.[17] One source claims that Richards was arrested in early 1879 in Austin, Texas.[46] There were even conflicting descriptions of Richards' appearance. Newspapers described him as being approximately six feet two inches tall[10][33][47] and "heavily built", with dark hair and blue eyes.[10][15][33] However, the account of a Dr. Moreland, who performed a phrenological examination of Richards before his execution,[Note 6] conflicted with these descriptions of him. In his examination report, Moreland said Richards had light brown hair and dark gray eyes.[49]

The Workingman's Friend, a Leavenworth, Kansas, newspaper, reported that Chicago authorities received part of the reward.[10]

After his arrest, Richards was jailed in Steubenville, Ohio. While there, he wrote two articles for the local newspaper, confessing to nine murders in a period of three years.[17][29] Sheriff David Anderson of Buffalo County, Nebraska, and Sheriff Martin of Kearney County,[19][22][Note 7] both of whom had pursued Richards to Ohio, returned him to Nebraska.[19][22] Due to local public outrage, Anderson and Martin feared that Richards would be lynched if he were returned to any of the localities where he had committed his crimes,[8][9] so it was decided to avoid taking him to these places initially.[33]

At the time of Richards' arrest, authorities suspected he was a member of a gang of outlaws who had plagued the state, or even the group's leader. Law enforcement was able to definitively link Richards to the nine murders to which he had confessed, and suggested that he might have killed even more,[8][9][10] but The Nebraska State Journal doubted this.[30]

Shortly before his trial, Richards predicted that he would be convicted and hanged for his crimes.[8][10][33] He was moved to a jail in Omaha on December 28, then transferred to Kearney by train. On December 30, a large crowd of enraged townsfolk gathered outside of the jail in Kearney where Richards was being kept. Fearing a lynching, authorities took "extra precautions" to ensure Richards' safety, as well as their own.[51] While being moved to the depot, Richards was said to have been impressed by the large crowd, asking whether the whole town was there to see him.[15] Eventually, the crowd dispersed and there were no further incidents during the rest of his stay in Kearney.[51]

Trial

Richards' trial began on January 16, 1879, in Minden, Nebraska, with Judge Gaslin presiding. The prosecution was led by a district attorney named Scofield,[52] and Richards' defense was led by a lawyer named Savage.[52] Scofield laid out two indictments for murder in the first degree, for the killings of the Harlson family and Anderson. Richards pled not guilty, arguing that Anderson's killing was in self-defense, and therefore justifiable.[3] The prosecution called seven witnesses to the stand.[52] They all testified to the state in which Anderson was found. Richards then was called to testify. When questioned by Scofield, he admitted to killing Anderson with a hammer after a heated argument, but reiterated that he had done so in self-defense. Richards said that, although repeatedly warned not to do so, Anderson had reached for a nearby hatchet.[53] The prosecution then entered into evidence the hammer that had been used to kill Anderson. Richards identified it as the murder weapon.[47]

After two hours of deliberation,[3][54] the jury found Richards guilty of the murders of the Harlsons and Anderson. He was sentenced to death by hanging,[13] and his execution date was set for April 26, 1879.[3] Richards was described as being "cheerful and indifferent" to both the proceedings and his conviction.[52] The Sedalia Weekly Bazoo reported that, shortly after his conviction, Richards managed to smuggle a knife into his cell, with the intention of using it to kill himself, but the weapon was discovered by the authorities, and confiscated before he could use it.[15] No other newspaper records corroborate this story, however.

Execution

When Richards was returned to Nebraska, the Omaha Herald reported that he "manifested supreme indifference to his lot, was perfectly willing to be brought direct to Kearney Junction and said he had as soon died one way as another."[24] Shortly after Richards' conviction, Sheriff Martin announced that his execution in Minden would be open to the public, even though Martin feared the attendance of a large number of spectators who could become violent.[55] In an effort to prevent a riot, an enclosure was constructed around the gallows to separate the expected crowd from Richards. However, tickets that allowed admittance into the restricted area were sold. Also, Richards was allowed to invite people; he chose members of the press whom he had befriended while in prison.[15]

Spectators at the execution were said to have numbered between 2,000[19] and 25,000.[31] As the crowd became increasingly agitated, the authorities pleaded with them to stay outside the enclosure, but guards were unable to prevent the spectators from beginning to destroy the barrier.[15][31][56] At precisely 1:00 p.m.,[31] Richards was led to the gallows by Martin and his deputy; this pacified the crowd. Upon ascending the gallows, Richards launched into an impassioned defense of his actions. He again claimed that the killing of Anderson was in self-defense, and also disavowed any involvement in the murders of the Harlson family,[31] and claimed he was the victim of a "wrongful conviction".[18] He then said he had found the Lord, "made [his] peace with God",[15] and "had faith in Christ", and asked the crowd to join him in singing the hymn "Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing".[31] Richards' final words were said to have been "Jesus be with me now!"[19] Reverend W. Sanford Gee, who presided over the execution, would later tell reporters he hoped Richards' professions of religious salvation were genuine, but allowed that they might not have been.[19]

At 1:17 p.m.[31][Note 8] on April 26,[13] 1879,[57] Richards was hanged. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat said it took fifteen minutes for him to die.[31][Note 9] Shortly after his execution, a photographer was able to capture a photograph of Richards' corpse propped inside a coffin.[60]

Aftermath

Local doctors hounded Richards before his execution, asking him to consent to donating his body, so they could perform an autopsy. He refused,[15][34] and would be buried in Minden.[2] Despite his gravesite being guarded,[34] his corpse was stolen the night after his execution—The Sedalia Weekly Bazoo suspected the doctors who had wanted to examine him[19]—but was returned to its resting place shortly thereafter.[61] Sometime later, his body was dug up once again; this time, Richards' bones were scattered on the streets of Kearney.[31][61] On November 1, 1882,[61] it was reported that Kearney County Gazette had obtained Richards' skull and placed it on display in the newspaper's office window.[2][61]

Pathology

Stephen Dee Richards[13]

After his arrest, many people described Richards as charismatic, and noted that he successfully concealed his dark nature under a polite, articulate, and handsome exterior;[15][33][62][63] a friend who accompanied Richards' autobiographer to his interviews said during one visit that Richards did not have the look of a murderer.[63] Contemporary observers remarked that Richards seemed to feel no guilt whatsoever about his crimes.[13][17][62] Numerous times between his arrest and his execution, Richards was asked why he had no empathy towards his victims or remorse for his crimes. Sometimes he simply refused to answer.[64] When he did choose to reply to this question, he gave conflicting responses. He would usually cite his associations with people of questionable morals,[21] and his time working at the Mount Pleasant Asylum, as deleterious influences.[22][23] When The Nebraska State Journal questioned him about his lack of remorse for the heinous murders he had committed, particularly those of the Harlson family, Richards recounted an event from his childhood. He had been tasked to kill a litter of kittens, and did so by bashing each of their heads against a tree. After he had killed all the kittens, he found that he felt no guilt about it, and in fact found the killing "fun".[65] However, he adamantly claimed that he did not enjoy inflicting pain upon others, and that in his younger years other people had considered him to be kind.[64] Reporters who interviewed him after his arrest were struck by his calm and collected behavior;[8][9][33] an article in the New York Daily Herald described him as being "carefree and cheerful".[16][38] In an interview for the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, Richards said he knew he would be executed for his crimes, but that he was unafraid of death and was "ready to meet it".[23] When the jury sentenced him to death, he was said to have been unconcerned and in good spirits.[3][47] The St. Louis Globe-Democrat (which doubted that he had actually committed nine murders) reported that Richards broke down during his final moments,[31] but this was contradicted by other newspaper accounts of his execution.[19][56]

Criminal psychology and profiling would not be used as an investigative technique until the Jack the Ripper murders in 1888, nine years after Richards' execution,[66] but in 2018, forensic psychologist Katherine Ramsland referred to Richards as "The Old West’s Ted Bundy". Both Richards and Bundy used their charisma to manipulate others, and both displayed a complete lack of remorse for their crimes. Ramsland also noted, however, that Bundy murdered for the purpose of sexual gratification, whereas Richards had no preferred method of killing or type of victim; furthermore, Bundy fought his execution, while Richards was indifferent to his death sentence. Ramsland also pointed out a possible reason for his violent behavior, citing a severe head injury that he received shortly before the killings started.[67] Richards himself would briefly mention this injury to the Sedalia Weekly Bazoo, claiming that he received the injury while traveling with several companions in the spring of 1877.[15] When pressed about the circumstances that led to the injury, Richards adamantly refused to divulge additional details on the incident.[64]

Throughout his travels, Richards used various aliases. In an account of his life published in The Sedalia Weekly Bazoo, Richards would admit to having used the false names George Gallagher, F.A. Hoge, and William Hudson. Richards also admitted to corresponding with various acquaintances under the names D.J. Roberts, J. Littleton, and W. A. Littleton.[15][25]

Legacy

At the time of Richards' arrest and execution, it was a popular belief that all criminals were of poor quality and limited education.[68] Richards would gain brief notoriety after his capture as he did not fit with the publics' preconception of criminals,[67] with reporters and members of the public often struck by his charisma, good looks, his education, and outspokenness.[15][33][67] Richards was featured in a handful of books and periodicals, the first of these was The Philosophy of Insanity: Richard, the Nebraska Fiend by Dr. John Sanderson Christianson was published on February 9, 1879.[69][70] A Nebraska State Journal interview with Richards prior to his execution was published in a book titled Life and Confession of Stephen Dee Richards, the Murderer of Nine Persons Executed at Minden, Nebraska, April 26, 1879. The book, published on May 1, 1879, five days after Richards' hanging, includes entries on other contemporary criminal cases as well.[71][72] After his execution, interest in Richards dwindled and he would subsequently fade from public memory.[67]

NET Nebraska's documentary Until He Is Dead: A History Of Nebraska's Death Penalty, featured Richards as a prime example of the public spectacle of the state's early executions; the documentary would mistakenly refer to him under his "Samuel Richards" alias.[60] An episode of the SyFy Channel documentary series Paranormal Witness, titled "The Nebraska Fiend", features a family who is purportedly being tormented by Richards' spirit.[73][74][75]

Notes

- Some newspaper accounts say Richards confessed to six murders.[3][16]

- A biography published shortly after Richards' execution claims that he was born in Ohio.[13]

- In his confession, Richards said the man had identified the murder victim as John, but Richards was unable to find out the dead man's surname;[26] however, it was given as Crawford in an article published ten days after Richards' execution.[31]

- The surname is spelled Harlson in the transcript of Richards' confession.[32] Other sources give different spellings, including Harrison,[10] Harleson,[33] Haralson[30] and Harrelson.[8][9][29]

- An article in the Lincoln Journal Star claimed that he fled instead to Red Cloud, and traveled to Chicago by way of Hastings. The article also stated that he used the alias "Samuel Richards" during his flight.[2]

- Phrenology supposedly predicts a person's mental traits by measuring bumps on the skull; influential in the 19th century, it is now considered pseudoscience.[48]

- One source listed Anderson and a Simon C. Ayer.[50]

- An alternate account reported by The Sedalia Weekly Bazoo would report that Richards was led to the gallows at 12:48 p.m.[15] This report would also list the song as "There Is a Fountain Filled with Blood", and the time of his hanging as 1:10 p.m.[19]

- Other accounts gave the amount of time as being five to ten minutes.[58][59]

References

- Columbus Journal 1878, p. 2.

- Lincoln Journal Star 2015.

- Nebraska Advertiser 1879, p. 2.

- Wilson 2014, p. 11.

- Jenkins 2004, p. 35.

- Hedblom & Teeters 1967, p. 202.

- Newton 2006, p. 317.

- Atchison Daily Champion 1878, p. 2.

- Belmont Chronicle 1879, p. 2.

- The Workingman's Friend 1879, p. 1.

- Sioux City Journal 1879, p. 2.

- Little Falls Transcript 1879, p. 2.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 1.

- New York Daily Herald 1878a, p. 7.

- Sedalia Weekly Bazoo 1879, p. 2.

- Walnut Valley Times 1879, p. 2.

- Wheeling Daily Intelligencer 1878, p. 2.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 46.

- Sedalia Weekly Bazoo 1879, p. 3.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 11.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 12.

- New York Times 1879, p. 2.

- Wheeling Daily Intelligencer 1878, p. 1.

- Omaha Herald 1878, p. 2.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 15.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 14.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, pp. 10–11.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 13.

- New York Daily Herald 1878b, p. 5.

- Nebraska State Journal 1878, p. 2.

- St. Louis Globe-Democrat 1879, p. 4.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 19.

- Quad-City Times 1878, p. 1.

- Wilson 2014, p. 12.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 16.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 17.

- Nebraska State Journal 1878, p. 16.

- New York Daily Herald 1879, p. 7.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 20.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, pp. 21–22.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 23.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 24.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 32.

- Nebraska State Historical Society 1942, p. 501.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 34.

- Ramsland 2006, p. 4.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 37.

- Stiles 2011, p. 12.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 38.

- Nebraska Senate Journal 1879, p. 501.

- Cincinnati Daily Star 1878, p. 1.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 35.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 36.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 33.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879a, p. 4.

- Nebraska Advertiser 1879b, p. 2.

- Newton 2006, p. 399.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 48.

- Saint Paul Globe 1879, p. 7.

- NETNebraska 2013, 8:08–8:44.

- Wilson 2014, p. 13.

- Press and Daily Dakotaian 1878, p. 5.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 7.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 41.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, pp. 6–7.

- Bonn 2017.

- Ramsland 2018.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 9.

- Bell 1885, p. 668.

- New York Public Library 1911, p. 303.

- Nebraska State Journal 1879b, p. 72.

- McDade 1961, p. 239.

- MovieTvTechGeeks 2016.

- Enk 2016.

- SyfyChannel 2016.

Sources

Books

- Anon. (May 1, 1879). Life and Confession of Stephen Dee Richards: The Murderer of Nine Persons, Executed at Minden, Nebraska, April 26, 1879 (1st ed.). State Journal Co. – via Internet Archive.

- Nebraska Senate Legislature (1879). Senate Journal of the Legislature of the State of Nebraska: Fifteenth Regular Session. 15. Journal Company, State Printers – via Google Books.

- Bell, Clark (1885). The Medico-Legal Journal. 49. Medico-Legal Society – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anon. (1911). Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 15. New York Public Library – via Google Books.

- John Lewis, ed. (1942). Messages and Proclamations of the Governors of Nebraska, 1854–1941. 1. Nebraska State Historical Society – via Google Books.

- Teeters, Negley; Hedblom, Jack (1967). "... Hang by the neck ...": the legal use of scaffold and noose, gibbet, stake, and firing squad from colonial times to the present. C. C. Thomas – via Google Books.

- Jenkins, Philip (December 2004). Moral Panic: Changing Concepts of the Child Molester in Modern America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10963-4 – via Google Books.

- McDade, Thomas (1961). The annals of murder: a bibliography of books and pamphlets on American murders from colonial times to 1900. University of Oklahoma Press – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newton, Michael (February 2006). The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (2nd ed.). Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-6987-3 – via Google Books.

- Ramsland, Katherine (2006). Inside the Minds of Serial Killers: Why They Kill. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99099-2 – via Google Books.

- Stiles, Anne (December 22, 2011). Popular Fiction and Brain Science in the Late Nineteenth Century (E-book). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139504904 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, R. (January 10, 2014). Legal Executions in Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma Including the Indian Territory: A Comprehensive Registry. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-8909-1 – via Google Books.

Periodicals and websites

- "Watching for a Wholesale Murderer". New York Daily Herald. New York, New York. December 14, 1878. p. 7. Retrieved October 15, 2019 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "The Journal". The Columbus Journal. Columbus, Nebraska. December 18, 1878. p. 2. Retrieved April 11, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "A Vile Murderer: A Prisoner Confesses to Having Murdered Nine Persons Over Three Years". The New York Daily Herald. New York, New York. December 25, 1878. p. 5. Retrieved October 30, 2019 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "The Steubenville Murderer Turns Out to be of Wheeling Origin". The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. Wheeling, West Virginia. December 25, 1878. p. 2. Retrieved April 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Friday, December 27, 1878". Nebraska State Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. December 27, 1878. p. 2. Retrieved April 6, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Richards, the Murderer". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa. December 28, 1878. p. 1. Retrieved January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "A Hardened Criminal". The Atchison Daily Champion. Atchison, Kansas. December 29, 1878. p. 2. Retrieved April 6, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Richards Back in Nebraska". The Cincinnati Daily Star. Cincinnati, Ohio. December 30, 1878. p. 1. Retrieved April 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Richards, the Kearney County Murderer, Gives for the First Time Full Details of His Crimes". The Omaha Herald. Omaha, Nebraska. December 31, 1878 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Nebraska's Boss Murderer: Richards on His Way to Kearney Junction, Where He Will End His Career". Press and Daily Dakotaian. Yankton, South Dakota. December 31, 1878. p. 5. Retrieved April 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Richards, The Mount Pleasant Criminal". Belmont Chronicle. Saint Clairsville, Ohio. January 2, 1879. p. 2. Retrieved April 6, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "The Nebraska Murderer: A Cool Confession of His Many Crimes". The New York Times. New York, New York. January 2, 1879. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Rande's Rival". The Workingman's Friend. Leavenworth, Kansas. January 3, 1879. p. 1. Retrieved April 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "He Killed Children as He Would Rabbits". New York Daily Herald. New York, New York. January 7, 1879. p. 7. Retrieved October 15, 2019 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "A Daring Demon". Little Falls Transcript. Little Falls, Minnesota. January 9, 1879. p. 2. Retrieved October 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "The Nebraska Fiend". Sioux City Journal. Sioux City, Iowa. January 17, 1879. p. 2. Retrieved April 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "State News and Notes". The Nebraska Advertiser. Brownville, Nebraska. January 23, 1879. p. 2. Retrieved July 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "The City". Nebraska State Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. April 26, 1879. p. 4. Retrieved April 6, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "The Craven Choked". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. St. Louis, Missouri. April 27, 1879. p. 4. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Scenes at a Hanging". New York Times. New York, New York. April 27, 1879. p. 2. Retrieved October 15, 2019 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Crimes and Casualties: Execution of Richards". The Saint Paul Globe. Saint Paul, Minnesota. April 27, 1879. p. 7. Retrieved May 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- T.B. Murdock (April 27, 1879). "Stephen D. Richards". El Dorado, Kansas: Walnut Valley Times. p. 2. Retrieved April 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "The Advertiser". The Nebraska Advertiser. Brownville, Nebraska. May 1, 1879b. p. 2. Retrieved April 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Dead and Damned: Stephen D. Richards Hanged". The Sedalia Weekly Bazoo. Sedalia, Missouri. May 6, 1879. pp. 2–3. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Bill Kelly (producer) (February 5, 2013). Until He Is Dead: A History Of Nebraska's Death Penalty (Television production). NET News. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- Bonn, Scott (December 4, 2017). "Criminal Profiling: The Original Mind Hunter". PsychologyToday.com. Sussex Publishers. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- Enk, Bryan (September 14, 2016). "Paranormal Witness News—Attend the Tale of Stephen Richards". SyFy.com. Bryan Enk. Retrieved October 7, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Nebraska's first legal executions". JournalStar.com (subscription required). Lincoln Journal Star. June 13, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2019.*"Paranormal Witness Recap—Nebraska Fiend". SyFy.com. SyFy Channel. September 14, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "'Paranormal Witness' 507 Nebraska Fiend aka Stephen Dee Richards visits". MovieTvTechGeeks.com. MTTG Staff. September 15, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- Ramsland, Katherine (January 18, 2018). "The Old West's Ted Bundy". PsychologyToday.com. Sussex Publishers. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

Further reading

- Dempsey, Tim (May 25, 2014). Well I'll Be Hanged: Early Capital Punishment in Nebraska. Sunbury Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-62006-336-1 – via Google Books.

- Bakken, Gordon (November 16, 2010). Invitation to an Execution: A History of the Death Penalty in the United States. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4858-6 – via Google Books.

- Bang, Roy (1952). Heroes Without Medals: A Pioneer History of Kearney County, Nebraska. Warp Publishing Company – via Google Books.

- Ramsland, Katherine (February 5, 2013). The Human Predator: A Historical Chronicle of Serial Murder and Forensic Investigation. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-61905-6 – via Google Books.