Taut-line hitch

The taut-line hitch is an adjustable loop knot for use on lines under tension. It is useful when the length of a line will need to be periodically adjusted in order to maintain tension. It is made by tying a rolling hitch around the standing part after passing around an anchor object. Tension is maintained by sliding the hitch to adjust the size of the loop, thus changing the effective length of the standing part without retying the knot.

| Taut-line hitch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Names | Taut-line hitch, Adjustable hitch, Rigger's hitch, Midshipman's hitch, Tent-line hitch, Tent hitch |

| Category | Hitch |

| Related | Rolling hitch, Two half-hitches, Trucker's hitch, Adjustable grip hitch |

| ABoK | #62, #1027, #1230, #1729, #1730, #1799, #1800, #1855, #1856, #1857, #1993 |

| Instructions | |

It is typically used for securing tent lines in outdoor activities involving camping, by arborists when climbing trees,[1] for tying down aircraft,[2] for creating adjustable moorings in tidal areas,[3] and to secure loads on vehicles. A versatile knot, the taut-line hitch was even used by astronauts during STS-82, the second Space Shuttle mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope.[4]

Naming

The adjustable loop forms of the rolling hitch and Magnus hitch, in addition to being called either of those two names, have also come to be known variously as the taut-line hitch,[3] tent-line hitch,[3] rigger's hitch,[3] adjustable hitch,[5] or midshipman's hitch.[5] These knots are generally shown as being based on one of three underlying hitches: two variants of the rolling hitch (ABOK #1734 and #1735) and the Magnus hitch (#1736).

These three closely related hitches have a long and muddled naming history that leads to ambiguity in the naming of their adjustable loop forms as well. The use of the Ashley reference numbers for these inconsistently named hitches can eliminate ambiguity when required. See the adjacent image for an illustration of these related knots.

An early use of the taut-line hitch name is found in Howard W. Riley's 1912 Knots, Hitches, and Splices, although it is shown in the rolling hitch form and suggested for use as a stopper.[6]

Tying

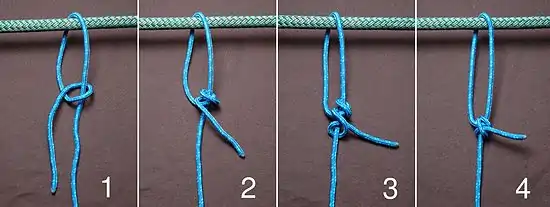

#1855

Ashley uses the name midshipman's hitch for this variation. Based on rolling hitch #1735, this version is considered the most secure but may be more difficult to adjust after being heavily loaded.

- Pass the working end around the anchor object. Bring it back alongside of the standing part and make a half-hitch around the standing part.

- Continue by passing the working end over the working part, around the standing part again and back through the loop formed in the first step. Make sure this second wrap tucks in between the first wrap and the working part of the line on the inside of the loop. This detail gives this version its additional security.

- Complete with a half-hitch outside the loop, made in the same direction as the first two wraps, as for a clove hitch.

- Dress by snugging the hitch firmly around the standing part. Load slowly and adjust as necessary.

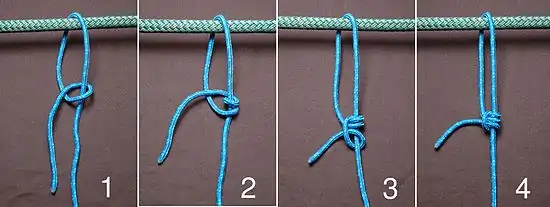

#1856

Based on rolling hitch #1734, this version is the one most often seen named taut-line hitch, typically in non-nautical sources. It is the method currently taught by the Boy Scouts of America.[7] The earliest Boy Scout Handbook to include the taut-line hitch was the 5th edition, published in 1948.[8] However it illustrated #1855, the variant shown above.[9]

- Pass the working end around the anchor object. Bring it back alongside of the standing part and make a half-hitch around the standing part.

- Continue with another wrap inside the loop, effectively making a round turn around the standing part.

- Complete with a half-hitch outside the loop, made in the same direction as the first two wraps, as for a clove hitch.

- Dress by snugging the hitch firmly around the standing part. Load slowly and adjust as necessary.

#1857

Based on Magnus hitch #1736, this is exactly as above but with the final hitch in the opposite direction. It can be more tricky to snug-up, since both lines emerge from the same side of the hitch, but it has less tendency to twist under load.

- Pass the working end around the anchor object. Bring it back alongside of the standing part and make a half-hitch around the standing part.

- Continue with another wrap inside the loop, effectively making a round turn around the standing part.

- Complete with a half-hitch outside the loop made in the opposite direction than the first two wraps, as for a cow hitch.

- Dress by snugging the hitch firmly around the standing part. Load slowly and adjust as necessary.

This is the form most commonly used for aircraft tie-down. One taut-line hitch is tied 15–30 cm from the aircraft and adjusted for tension, then a second taut-line hitch is tied 5–20 cm further from the aircraft and finished with a half-hitch. Wind-induced lift tends to pull the knot tighter, gust-induced oscillations tend to damp-out, and once the half hitch is undone, pushing the lower working rope up easily releases both hitches even amid icing.

Adjusting

.svg.png.webp)

Once snug and set, the hitch can be adjusted as needed. To tighten the line with respect to a load attached to the standing part, the user can grasp the standing part with one hand inside of the loop and pull toward the anchor object. The hitch may be grasped with the other hand and as slack develops within the loop, the hitch slid away from the anchor object, taking up the slack and enlarging the loop. To loosen, the hitch may be slid toward the anchor object, making the loop smaller and lengthening the standing part.

Security

Although the three variations are similar, they do have distinct properties when put to use. Ashley[10] and others[3][11] suggest that #1855 is preferred as being more secure. Either #1856 or #1857 is also acceptable, especially if ease of adjustment is desired over security.[12][13] Ashley states #1857 has less tendency to twist.[5]

These hitches may not hold fast under all conditions, and with lines made from particularly stiff or slick modern fibers (e.g. polypropylene) these hitches can be difficult to make hold at all. Sometimes they can be made more secure by using additional initial wraps and finishing half-hitches.[13]

Friction hitches[14]

These as a family are called Friction Hitches[1] of hold and release to slide hitches[15]

The similar ABoK numbers are in ABoK's unique "CHAPTER 22: HITCHES TO MASTS, RIGGING AND CABLE (LENGTHWISE PULL)" [5] 1st paragraph reads: "To withstand a lengthwise pull without slipping is about the most that can be asked of a hitch. Great care must be exercised in tying the following series of knots, and the impossible must not be expected."[5] A Friction Hitch is on a rope column that you are grabbing with "LENGTHWISE PULL" force wise in this chapter.[5] Not at the best (right) angle to host mount the rest of the book speaks of and shows for working hitches and thus chapter title and preface states. And so, the Friction Hitches are contained in this chapter on the errant pull angle stated as "LENGTHWISE PULL".[5] Book shows a 'linear' Half Hitch to precede a Timber Hitch (that shows should pull at right angle to spar) so can pull LENGTHWISE in ABoK#"1733. The TIMBER HITCH AND HALF HITCH" Killick hitch perhaps best demonstrates the directional force effect as he shows it as the very first knot in the chapter right after the previous discussion as context .[5] After showing the Half-Hitch preceding as only conversion for the direction adds: "The knot appears to be universal and invariable"! [5]

See also

References

- Adams, Mark (April 2005), "Son of a Hitch: A Genealogy of Arborists' Climbing Hitches" (PDF), Arborist News, International Society of Arboriculture

- Pardo, Jeff (October 2004), "Tying the Knot: Know the ropes so your aircraft won't be gone with the wind", Flight Training, Airplane Owners and Pilots Association

- Toss, Brion (1998), The Complete Rigger's Apprentice, Camden: International Marine, pp. 54–55

- Nugent, Tom (1997). "Blanketing the Hubble". University of Delaware Messenger. 6 (3).

- Ashley, Clifford W. (1944), The Ashley Book of Knots, New York: Doubleday, p. 304

- Riley, Howard W. (January 1912). "Knots, Hitches, and Splices". The Cornell Reading-Courses. Rural Engineering Series No. 1. Ithaca, NY: New York State College of Agriculture at Cornell University. 1 (8): 1425. Retrieved 2011-11-26. As not collected in Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, 136th Session, 1913, Vol. 19, No. 29, Part 5.

- Boy Scouts of America (2009), The Boy Scout Handbook (12th ed.), Irving: BSA, p. 385

- Snowden, Jeff (2009), The Boy Scout Handbook 1910-Today (4th ed.), Troop 97 BSA

- Boy Scouts of America (1949), Handbook for Boys (5th ed.), BSA, pp. 94–95

- Ashley(1944), p. 298

- Trower, Nola (1995), Helmsman Guides: Knots and Ropework, Wiltshire: Helmsman Books, pp. 31–32

- Ashley(1944), p. 296

- Toss, Brion (1990), Chapman's Nautical Guides: Knots, New York: Hearst Marine Books, pp. 30–32

- Bavaresco, Paolo (2002). "Ropes and Friction Hitches used in Tree Climbing Operations" (PDF). Professional Association of Climbing Instructors PACI.com.

- Adams, Mark (October 2004). "Climber's Corner an Overview of Climbing Hitches" (PDF). treebuzz.com.